by Dr. Mark Beliles 1 and Dr. David Barton 2

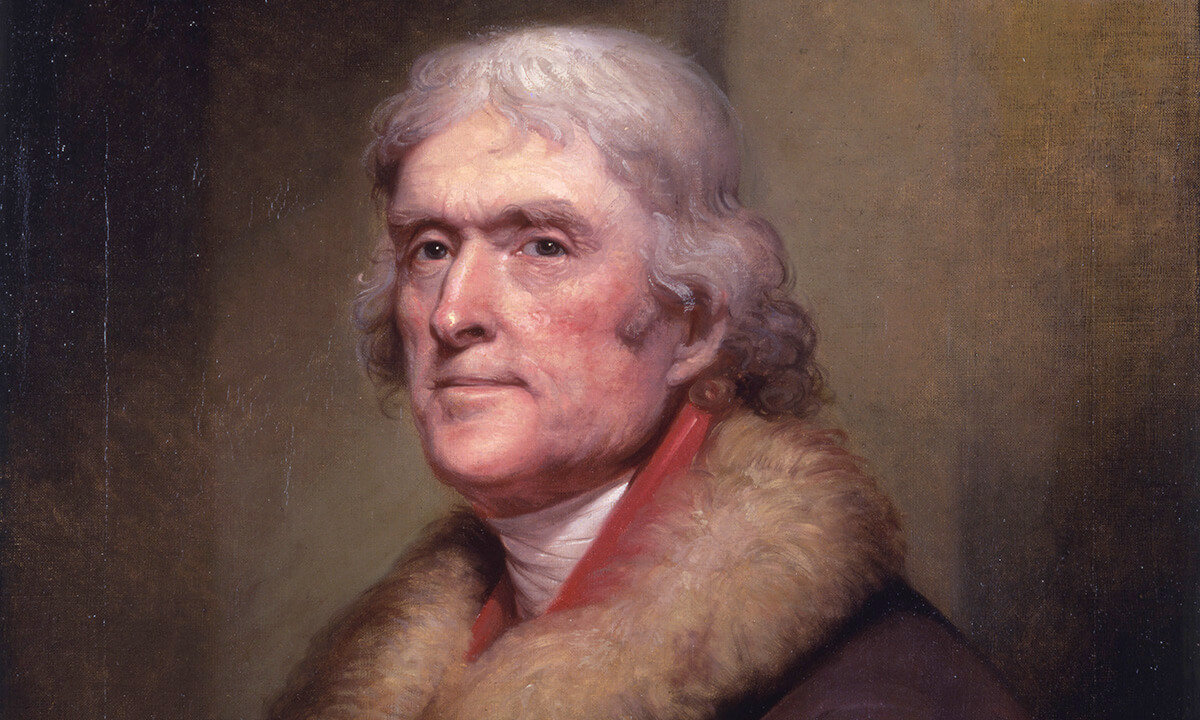

Jefferson also founded the first intentionally secularized university in America. His vision for the University of Virginia was for education finally free from traditional Christian dogma. He had a disdain for the influence that institutional Christianity had on education. At the University of Virginia there was no Christian curriculum and the school had no chaplain. Its faculty were religiously Deists and Unitarians.

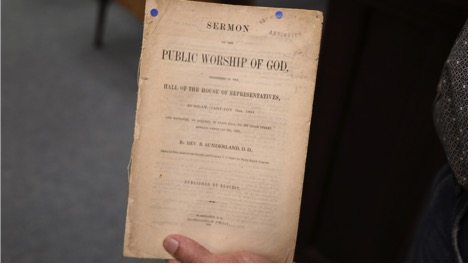

Many other professors make similar claims:

- After Jefferson left the presidency in 1809, he embarked on what has unequivocally been determined as his finest architectural design achievement: the University of Virginia….A Deist and a Secular Humanist, Jefferson rejected the religious tradition that had provided the foundation for the colonial universities. 3 PROFESSOR ANITA VICKERS, PENN STATE UNIVERSITY

- The university which Thomas Jefferson established at Charlottesville in Virginia was America’s first real state university….[I]ts early orientation was distinctly and purposely secular. 4 PROFESSOR JOHN BRUBACHER, YALE UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN; PROFESSOR WILLIS RUDDY, FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON UNIVERSITY

- The University of Virginia affords the first historical instance in any country in which the university was deliberately and purposefully conceived as an agency of the realm of the secular state. 5 PROFESSOR LEWIS P. SIMPSON, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY

- Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia, founded in 1819…became the first purely secular institution. 6 PROFESSOR CATHERINE COOKSON, VIRGINIA WESLEYAN COLLEGE

- No part of the regular school day was set aside for religious worship….Jefferson did not permit the room belonging to the university to be used for religious purposes. 7 PROFESSOR LEONARD LEVY, SOUTHERN OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY, CLAREMONT GRADUATE SCHOOL

Sadly, the current academic over-emphasis on peer-review among professors has caused many to develop the regrettable tendency of heavily reading, quoting, and citing each other rather than actual historical documents related to the object of their inquiry. That is, rather than saying “Thomas Jefferson says that the University of Virginia was founded in order to . . .”, they instead say, “Professor _____ says that Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia in order to . . .” Consequently, when one academic writer makes a particular claim, many others repeat that claim as though it were indisputable fact – even if that claim can be factually disproved. As a result of this modern academic malpractice, four oft-repeated claims have emerged about Jefferson’s founding of the University of Virginia:

1. Jefferson founded a deliberately secular university

2. Jefferson sought out Unitarians to be its faculty

3. Jefferson barred religious activities and instruction from the program of the school

4. Affirming its commitment to secularism, the University of Virginia had no chaplain

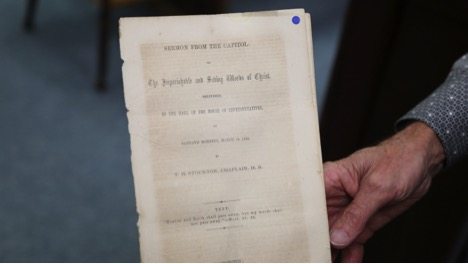

It will be seen below that numerous original documents incontestably disprove these four assertions, including Jefferson’s own writings, the records of the University of Virginia, the writings of those involved in the formation of the University, and other public records of that day.

Illustrative of this pattern, in 1636, Harvard was founded by and for CONGREGATIONALISTS to train Congregationalist ministers (as was Yale in 1701 and Dartmouth in 1769); in 1692, the College of William and Mary was founded by and for the ANGLICANS to train Anglican ministers (as was the University of Pennsylvania in 1740, Kings College in 1754, and the College of Charleston in 1770); in 1746, Princeton was founded by and for PRESBYTERIANS (as was Dickinson in 1773 and Hampden-Sydney in 1775); in 1764, the College of Rhode Island (now Brown University) was founded by the BAPTISTS; in 1766, Queens College (now Rutgers) was founded by and for the DUTCH REFORMED; in 1780, Transylvania University was founded by and for the DISCIPLES OF CHRIST; etc.

Jefferson and his Board of Visitors (i.e., Regents) founded the University of Virginia as a school not affiliated with only one denomination; it was specifically founded as a trans-denominational school. Consequently, it did not incorporate the three features so commonly associated with other universities at that time, thus causing modern critics wrongly to claim that it was founded as a secular university.

In implementing a trans-denominational approach, Jefferson was embracing the position that had been nationally set forth by an evangelical Presbyterian clergyman, Samuel Knox of Baltimore, whom Jefferson later asked to be his first faculty member at the University of Virginia. 8 In 1799, Knox penned an educational policy piece proposing the formation of a state university that would not have just one specific theological school but rather would invite many denominations to establish schools at the university; the various denominations would therefore all work together in mutual cooperation rather than in competition. 9 Jefferson agreed with this philosophy, and it was this model that he employed at the University of Virginia.

Significantly, thirty years earlier, Jefferson had begun actively promoting Christian non-preferentialism in his famous 1786 Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, which disestablished the Anglican Church as the only legally recognized and established denomination in Virginia and instead placed all Christian denominations on an even footing. Because the charter for the new University had been issued by the state legislature, the school was required to conform to the denominational non-preferentialism set forth in the Virginia Statute and the Virginia Constitution.

Since the University would have no single denominational seminary but rather the seminaries of many denominations, Jefferson and the Visitors (i.e., Regents) decided that there should be no clergyman as university president and no specified Professor of Divinity, either of which might wrongly cause the public to think that the University favored the particular denomination with which the university president or Professor of Divinity was affiliated. 10 As Jefferson explained:

In conformity with the principles of our constitution which places all sects [denominations] of religion on an equal footing – with the jealousies of the different sects in guarding that equality from encroachment and surprise, and with the sentiments of the legislature in favor of freedom of religion manifested on former occasions [as in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom] – we have proposed no Professor of Divinity. 11

But the fact that the school would have no Professor of Divinity did not mean that religious instruction would not take place. To the contrary, Jefferson personally ensured that religious instruction would occur, directing that the teaching of . . .

the proofs of the being of a God – the Creator, Preserver, and Supreme Ruler of the Universe – the Author of all the relations of morality and of the laws and obligations these infer – will be within the province of the Professor of Ethics. 12

Jefferson made sure that the teaching of religion to students definitely would occur, but he merely placed it under a professor different than was traditionally used; Jefferson absolutely did not eliminate religious instruction. In fact, he wanted it clearly understood that not having a Professor of Divinity definitely did not mean that the University would be secular:

It was not, however, to be understood that instruction in religious opinions and duties was meant to be precluded by the public authorities as indifferent to the interests of society. On the contrary, the relations which exist between man and his Maker – and the duties resulting from those relations – are the most interesting and important to every human being and the most incumbent on his study and investigation. 13

(Incidentally, in 1896 after the trans-denominational reputation of the school was fully established, a Bible lectureship was established by the University; by 1909, it had become a full Professorship of Divinity.)

Jefferson also made clear that the religious instruction which would occur at the University would incorporate the numerous religious beliefs on which Christian denominations agreed rather than just the specific theological doctrines of any one particular denomination. As he explained, “provision…was made for giving instruction in…the earliest and most respected authorities of the faith of every sect [denomination] and for courses of ethical lectures developing those moral obligations in which all sects agree.” 14

(This trans-denominational approach to teaching Christian beliefs and morals was so common in America that famous writer Alexis de Tocqueville reported:

The sects [denominations] which exist in the United States are innumerable. They all differ in respect to the worship which is due from man to his Creator, but they all agree in respect to the duties which are due from man to man. Each sect adores the Deity in its own peculiar manner, but all the sects preach the same moral law in the name of God….[A]lmost all the sects of the United States are comprised within the great unity of Christianity, and Christian morality is everywhere the same. 15

Jefferson made clear to the public on multiple occasions and in several different writings that religious and moral instruction definitely would be part of regular academic instruction at the University of Virginia. He also expounded on his design to invite many denominations to participate in student instruction:

We suggest the expediency of encouraging the different religious sects to establish, each for itself, a professorship of their own tenets on the confines of the university so near as that their students may attend the lectures there and have the free use of our library and every other accommodation we can give them….[B]y bringing the sects [denominations] together and mixing them with the mass of other students, we shall soften their asperities [harshness], liberalize and neutralize their prejudices [prejudgment without an examination of the facts], and make the general religion a religion of peace, reason, and morality. 16

Jefferson observed that a positive benefit of this approach was that it “would give to the sectarian Schools of Divinity the full benefit of the public [university] provisions made for instruction” 17 and “leave every sect to provide as they think fittest the means of further instruction in their own peculiar tenets.” 18 Jefferson also pointed out that an additional benefit of this arrangement would be that “such establishments would offer the further and great advantage of enabling the students of the University to attend religious exercises with the Professor of their particular sect.” 19 The students would be offered many denominational choices, and Jefferson made clear that students would be expected to participate in the various denominational schools. 20

Jefferson’s nondenominational approach caused Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, and others to give the University the friendship and support necessary to make the new school succeed. Consider Presbyterian minister John Holt Rice as an example.

Holt was a nationally-known religious leader. In 1813, he helped found the Virginia Bible Society 21 (of which Jefferson was a significant financial contributor 22 ); in 1818 he started the Virginia Evangelical and Literary Magazine to emphasize Christianizing the culture and report on various revivals across the country; in 1819, he was elected national moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church; and in 1822, he was offered the presidency of Princeton but instead accepted the Chair of Theology at Hampden-Sydney College. Rice – an evangelical Presbyterian – fully supported the University of Virginia 23 and worked diligently “in creating a popular sentiment favorable to the passage of the University bill [in the General Assembly].” 24

Rice’s support of Jefferson’s school was no small endorsement and was representative of the support that the school received from other denominations. They understood that the University of Virginia was not secular but rather trans-denominational. As the official Centennial of the University of Virginia affirmed in 1921, “Thomas Jefferson…aimed no blow at any religious influence that might be fostered by it. The blow was at sectarianism only.” 25 (emphasis added)

Clearly, Jefferson’s own writings and the records of the University absolutely refute the notion that he founded a secular university; and clergyman, historian, and author Anson Phelps Stokes (second-in-command at Yale and then resident canon at the National Cathedral in Washington, D. C.) correctly concluded about Jefferson that “even in establishing a quasi-state university on broad lines, the greatest liberal who took part in founding our government felt that instruction in the fundamentals of Christian theism and Christian worship were both important and proper.” 26

(Incidentally, another indicator of the non-secular nature of the University what that when construction began in 1817, a special prayer was offered at the laying of the cornerstone, in the presence of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, beseeching “Almighty God, without invocation to Whom no work of importance should be begun, bless this undertaking and enable us to carry it on with success – protect this college, the object of which institution is to instill into the minds of youth principles of sound knowledge, to inspire them with the love of religion and virtue, and prepare them for filling the various situations in society with credit to themselves and benefit to their country.” 27 Significantly, it was Jefferson and his Board of Visitors who made the arrangements and approved both the prayer and the Scriptures for that ceremony.)

Jefferson eventually settled on ten teaching positions at the University; 31 and significantly, when those positions were filled, notwithstanding the errant claims of modern critics, none of the professors was Unitarian. In fact, two of the original professors hired by Jefferson (George Tucker, Professor of Moral Philosophy, and Robley Dunglison, Professor of Anatomy and Medicine) were later asked about Jefferson’s views on the religious beliefs of the professors he had selected – specifically, had Jefferson sought to fill the faculty with Deists or Unitarians? To that question, Professor Dunglison replied:

I have not the slightest reason for believing that Mr. Jefferson was in any respect guided in his selection of professors of the University of Virginia by religious considerations…. In all my conversations with Mr. Jefferson, no reference was made to the subject. I was an Episcopalian, so was Mr. Tucker, Mr. Long, Mr. Key, Mr. Bonnycastle, and Dr. Emmet. Dr. Blaettermap, I think, was a Lutheran, but I do not know so much about his religion as I do about that of the rest. There certainly was not a Unitarian among us. 32 (emphasis added)

Professor Tucker agreed, declaring:

I believe that all the first professors belonged to the Episcopal Church, except Dr. Blaetterman, who, I believe, was a German Lutheran….I don’t remember that I ever heard the religious creeds of either professors or Visitors [Regents] discussed or inquired into by Mr. Jefferson – or anyone else. 33

Jefferson simply did not delve into the denominational affiliations or specific religious beliefs of his faculty; what he sought was professors who had proper knowledge and deportment. As he once told his close friend and fellow-patriot and co-signer of the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush:

For thus I estimate the qualities of the mind: 1. good humor; 2. integrity; 3. industry; 4. science. The preference of the first to the second quality may not at first be acquiesced in, but certainly we had all rather associate with a good-humored, light-principled man than with an ill-tempered rigorist in morality. 34

It was by applying such standards that Jefferson once invited Thomas Cooper to be Professor of Chemistry and Law, 35 but when it became known that Cooper was a Unitarian, a public outcry arose against him and Jefferson and the University withdrew its offer to him. 36

Obviously, this type of original documentary evidence concerning Jefferson and the religious views of his faculty is ignored by many of today’s writers and educators. However, Professor Roy Honeywell of Eastern Michigan University did review the original historical evidence rather than just the claims of other professors, and he correctly concluded:

In general, Jefferson seems to have ignored the religious affiliations of the professors. His objection to ministers was because of their active association with sectarian groups – in his day a fruitful source of social friction. The charge that he intended the University to be a center of Unitarian influence is totally groundless. 37

There simply is no historical merit to the claim that Jefferson sought out Unitarians or Deists in order to make the school a seedbed of Unitarianism.

For example, he directed the Professor of Ancient Languages to teach Biblical Greek, Hebrew, and Latin to students so that they would be equipped to read and study the “earliest and most respected authorities of the Christian Faith.” 38 Wanting the writings of those Christian authorities and “the writings of the most respected authorities of every sect [denomination]” 39 to be placed in the university library, Jefferson asked James Madison to prepare such a list for the library. 40

In September 1824, Madison returned his list to Jefferson in which he included the works of the Alexandrian Fathers (the early Alexandrian church fathers included Clement, Origen, Pantaenus, Cyril, Athanasius, and Didymus the Blind); Latin authors such as St. Augustine; the writings of St. Aquinas and other Christian leaders from the Middle Ages; and the works of Erasmus, Luther, Calvin, Socinius, and Bellarmine from the Reformation era. Madison’s list also included more modern theologians and religious writers such as Grotius, Tillotson, Hooker, Pascal, Locke, Newton, Butler, Clarke, Wollaston, Edwards, Mather, Penn, Wesley, Priestley, Price, Leibnitz, and Paley. 41

In addition to the religious instruction by the Professor of Ancient Language, Jefferson succinctly stated that he had personally arranged the curriculum so that religious study would also be an inseparable part of the study of law and political science. 42 It is clear that Jefferson took numerous steps to secure religious instruction as part of academic studies.

But Jefferson not only sought to ensure that students would study about God, he also made provision for them to worship God. In the early planning stages of the University, he had stipulated “that a building…in the middle of the grounds may be called for in time in which may be rooms for religious worship”; 43 later, he specifically ordered that in the University Rotunda, “one of its large elliptical rooms on its middle floor shall be used for…religious worship” and that “the students of the University will be free and expected to attend.” 44 (emphasis added).

Clearly, the modern claim that there was no Christian curriculum at the University of Virginia is demonstrably false not only by Jefferson’s own writings but also by those of University Visitors such as James Madison.

[F]or several years after its operations commenced [founded in 1819, it opened to students in 1825]….It was by many supposed that infidelity was interwoven with the very elements of its existence, and consequently its early history was overhung with the clouds of discouragement. How far these prejudices were just may be ascertained from the fact (not generally known) that in the original organization of this establishment, the privilege of erecting Theological Seminaries on the territory [grounds] belonging to the university was cheerfully extended to every Christian denomination within the limits of the State.

In the present arrangement for religious services at the University, you have all the evidence that can with propriety be asked respecting the favorable estimate which is placed upon the subject of Christianity.

The chaplains, appointed annually and successively from the four prominent denominations in Virginia [Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist], are supported by the voluntary contributions of professors and students….

Beside the regular services of the Sabbath, we have….also a Sabbath School in which several of the pious students are engaged.

The monthly concert for prayer is regularly observed in the pavilion which I occupy.

In all these different services we have enjoyed the presence and the smiles of an approving Redeemer….[and i]t has been my pleasure on each returning Sabbath to hold up before my enlightened audience the cross of Jesus – all stained with the blood of Him that hung upon it – as the only hope of the perishing. 45 (emphasis added)

Another ad run by the University similarly noted:

Religious services are regularly performed at the University by a chaplain, who is appointed in turn from the four principal denominations of the State. And by a resolution of the Faculty, ministers of the Gospel and young men preparing for the ministry may attend any of the schools without the payment of fees to the professors. 46 (emphasis added)

It was the custom of that day that all faculty members receive their salaries from fees paid by the students directly to the professors, but the University waived those fees for students studying for the Gospel ministry. If the University of Virginia truly held the secular orientation claimed by so many of today’s writers, then why did it extend preferential treatment to students pursuing religious careers? Surely a truly secular university would give preference to secular-oriented students rather than religiously-oriented ones – something the University of Virginia did not do.

The University of Virginia did indeed have chaplains – albeit not in its first three years. At the beginning when the University was establishing its reputation as a non-denominational university, there was no appointed chaplain for the same reasons there had been no clergyman as president and no Professor of Divinity: an ordained clergyman in any of those three positions might send an incorrect signal that the University was aligned with the denomination of that specific clergyman. Furthermore, clergymen representing each seminary were on campus and available to minister to students. But by 1829, the non-denominational direction of the University had been established, so President Madison (who became Rector of the University after Jefferson’s death in 1826) announced “that [permanent] provision for religious instruction and observance among the students would be made by…services of clergymen.” 47

The University therefore extended official recognition to one primary chaplain for the students, with the chaplain position to rotate annually among the major denominations. (According to Jefferson, “about 1/3 of our state is Baptist, 1/3 Methodist, and of the remaining 1/3, two parts may be Presbyterian and one part Anglican.” 48 ) In 1829, Presbyterian clergyman Rev. Edward Smith became the first chaplain – an official university position, but unpaid. In 1833 after three-fourths of the students pledged their own money for the chaplain’s support, Methodist William Hammett became the first paid chaplain, leading Sunday worship and daily morning prayer meetings in the Rotunda. In 1855, the University built a parsonage to provide a residence on the grounds for the university chaplain. Significantly, many of the University of Virginia’s chaplains went on to famous religious careers, including Episcopalian Joseph Wilmer, Presbyterians William White, William H. Ruffner, and Robert Dabney, Baptists Robert Ryland and John Broaddus, and many others.

Clearly, the University of Virginia did have chaplains, and it placed a strong emphasis on the spiritual preparedness of its students through the important ministry of those chaplains.

— — — ◊ ◊ ◊ — — —

The charge that Jefferson founded the University of Virginia as a secular institution that excluded traditional religious instruction from students and instead inculcated them in the principles of Deism and Unitarianism is completely false. In fact, if anyone examines the original primary source documents and then claims otherwise, they are (to use the words of military chaplain William Biederwolf, 1867-1939) just as likely to “look all over the sky at high noon on a cloudless day and not see the sun.” 49

Endnotes

1. Mark Beliles is founder of the Providence Foundation and vice-President of its Biblical Worldview University. Mark is chairman of the City of Charlottesville’s Historic Resources Committee and the annual “Governor Jefferson Thanksgiving Festival,” has convened a number of academic symposiums at the University of Virginia, and lectures throughout the United States, Asia, Africa, and Europe. He earned his PhD from Whitefield Theological Seminary (dissertation: Churches and Politics in Jefferson’s Virginia). Beliles’ extensive primary source documentary research on Jefferson highlights Jefferson’s founding of the Calvinistical Reformed Church of Charlottesville during the Revolution and then demonstrates that Jefferson’s subsequent rejection of Trinitarian language and creeds later in life was mainly from the influence of the evangelical “primitive” and “restoration” church movement that arose in the Central Virginia Piedmont rather than being the result of secular European Enlightenment, New England Unitarianism, or Deism. For more information contact Mark Beliles at mbeliles@gmail.com or call 434-249-4032.

2. David Barton is the author of numerous books and the president of WallBuilders, a national pro-family organization dedicated to “presenting America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on our moral, religious, and constitutional heritage.” a consultant to state and federal legislators and has been involved in several federal court cases, including at the U.S. Supreme Court. He personally owns thousands of original documents from the Founding Era, including handwritten documents of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Barton has been appointed by State Educational Boards in California, Texas, and other states to help write the history and government standards for students in those states. He has served as an editor for national publishers of school history textbooks. Barton is the recipient of several national and international awards, including the Daughters of the American Revolution Medal of Honor (1998), the George Washington Honor Medal (2006, 1995), Who’s Who in America (2009, 2008, 2000, 1999, 1998, 1997), Who’s Who in the World (2009, 2008, 2004, 2000, 1999, 1998, 1997, 1996), Who’s Who in American Education (2007, 2004, 1997, 1996), International Who’s Who of Professionals (1996), Two Thousand Notable American Men Hall of Fame (1995), Who’s Who Among Outstanding Americans (1994), Who’s Who in the South and Southwest (2001, 1999, 1997, 1995), Outstanding Young Men in America (1990), and numerous other awards. He is the author of numerous books and holds a B.A. from Oral Roberts University and an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from Pensacola Christian College. Time Magazine has listed him as one of the 25 Most Influential Evangelicals in America.

3. Anita Vickers, The New Nation (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 2002), p. 74.

4. John S. Brubacher & Willis Rudy, Higher Education in Transition: A History of American Colleges and Universities (Transaction Books, 1997), pp. 147-149.

5. Lewis P. Simpson, Imagining Our Time: Recollections and Reflections on American Writing (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007), p. 47. See also Lewis P. Simpson, “Jefferson and the Crisis of the American University,” The Virginia Quarterly Review, 2000, pp. 388-402 (at: https://www.vgronline.org/articles/2000/summer/simpson-jefferson).

6. Encyclopedia of Religious Freedom, Catherine Cookson, editor (Taylor & Francis, 2003), p. 140.

7. Leonard Levy, “Jefferson, Religion and the Public Schools,” Separation of Church and State (at: https://candst.tripod.com/tnppage/jeffschl.htm), from Levy’s book Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side (1989).

8. Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Andrew A. Lipscomb, editor (Washington, D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 365-366, “Minutes of the Visitors of Central College,” July 28, 1817. Jefferson also wrote a letter to Knox on February 12, 1810, discussing the proper training of youth – America’s next generation of national leaders. As Jefferson correctly observed to Knox, “The boys of the rising generation are to be the men of the next, and the sole guardians of the principles we deliver over to them.” (See Jefferson, Writings, (1904), Vol. XII, pp. 359-361, letter to Rev. Samuel Knox, February 12, 1810.)

9. Samuel Knox, Essay on the Best System of Liberal Education (Baltimore: Warner and Hanna, 1799), pp. 78-79.

10. Henry Randall’s early biography of Jefferson (published in 1858) explains that, “The omission in the plan of the University to make provision for religious instruction [by establishing a specific Professor of Divinity] has been misconstrued by many candid persons because they have not understood the true nature of that institution. They look round on the American colleges and see such a provision generally made in them. But these schools have mostly been founded by particular sects… [If Virginia’s state university] was placed under the religious supervision or influence of any particular sect, the public money of all sects would be used for the benefit of one.” See Henry S. Randall, The Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1858), Vol. III, pp. 469-470.

11.Thomas Jefferson, “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 [The Rockfish Gap Report], from The University of Virginia (at: https://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefRock.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1). See also Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 413-414, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 7, 1822.

12. Thomas Jefferson, “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 [The Rockfish Gap Report], from The University of Virginia (at: https://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefRock.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1).

13. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 414, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 7, 1822.

14. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 414, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 7, 1822.

15. Alexis De Tocqueville, Democracy in America, (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1851), Vol. I, p. 331.

16. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 405-406, letter to Dr. Thomas Cooper, November 2, 1822.

17. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 415, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 7, 1822.

18. Thomas Jefferson, “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 [The Rockfish Gap Report], from The University of Virginia (at: https://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefRock.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1).

19. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 415-416, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 7, 1822.

20. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 449-450, A Meeting of the Visitors of the University of Virginia on Monday the 4th of October, 1824.

21. William Henry Foote, Sketches of Virginia, Historical and Biographical (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1856), p. 325. See also Address of the Managers of the Bible Society of Virginia to the Public (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, 1814), p. 8.

22. Thomas Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIV, p. 81, letter to Samuel Greenhow, January 31, 1814.

23. See, for example, his articles expressing his strong support in his Virginia Evangelical and Literary Magazine, such as that in Vol. I, 1818, p. 548 (printed in A.J. Morrison, The Beginnings of Public Education in Virginia, 1776-1860 (Richmond: Davis Bottom, 1917), p. 38), wherein after announcing his support, he promised to return to the subject as often as necessary, declaring: “The writer of this will return to it again and again, and however feeble his abilities, will give them, in their best exercise, to an affair so deeply involving the best interests of his country.”

24. Philip Alexander Bruce, History of the University of Virginia, 1819-1919 (New York: The MacMillian Company, 1920), Vol. I, p. 204.

25. The Centennial of the University of Virginia 1819-1921, John Calvin Metcalf, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1922), p. 6.

26. Anson Phelps Stokes, Church and State in the United States (New York: Harper & Bothers Publishers, 1950), Vol. I, p. 338.

27. Alexander Garrett, “Outline of Cornerstone Ceremonies,” October 6, 1817, from The University of Virginia (at: https://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=Jef1Gri.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=47&division=div1). See also Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time: The Sage of Monticello (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1981), Vol. VI, p. 265.

28. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 365-366, “Minutes of the Visitors of Central College,” July 28, 1817. Jefferson also wrote a letter to Knox on February 12, 1810, discussing the proper training of youth – America’s next generation of national leaders. As Jefferson correctly observed to Knox, “The boys of the rising generation are to be the men of the next, and the sole guardians of the principles we deliver over to them.” (See Jefferson, Writings, (1904), Vol. XII, pp. 359-361, letter to Rev. Samuel Knox, February 12, 1810.)

29. Samuel Knox, The Scriptural doctrine of future punishment vindicated : in a discourse from these words, “And these shall go away into everlasting punishment, but the righteous into life eternal.” Math. XXV, & 46th. : To which are prefixed some prefatory strictures on the lately avowed religious principles of Joseph Priestley, L.L.D. F.R.S. &c. &c. Particularly in a discourse delivered by him in the church of the Universalists, in Philadelphia, and published in1796. –Entitled: “Unitarianism explained and defended” &c (Georgetown: Green, English & Co., 1796).

30. See Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 367, Board of Visitors, Minutes, Charlottesville, October 7, 1817, and Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 390, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 2-3, 1820.

31. In the 1818 report by Jefferson and the Board of Visitors, Jefferson announced: “We are further of opinion, that after declaring by law that certain sciences shall be taught in the University, fixing the number of professors they require, which we think should, at present, be ten.” See Thomas Jefferson, “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 [The Rockfish Gap Report], from The University of Virginia (athttps://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefRock.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1).

32. Henry S. Randall, The Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1858), Vol. III, pp. 467-468, letter from Robley Dunglison to Henry S. Randall, June 1, 1856.

33. Randall, The Life of Thomas Jefferson (1858), Vol. III, p. 467, letter from George Tucker to Henry S. Randall, May 28, 1856.

34. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XI, p. 413, letter to Benjamin Rush, January 3, 1808.

35. See Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 367, Board of Visitors, Minutes, Charlottesville, October 7, 1817.

36. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 389, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 2-3, 1820. See also “Thomas Cooper (US Politician),” Wikipedia, October 8, 2008 (at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Cooper_(US_politician); “Thomas Cooper Society,” University of South Carolina, February 20, 2008 (at: https://www.sc.edu/library/develop/tcsinfo.html).

37. Roy Honeywell, The Educational Work of Thomas Jefferson (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931), p. 92.

38. Thomas Jefferson, “Report to the President and Directors of the Literary Fund,” The Avalon Project, October 7, 1822 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jeffrep3.asp). Thomas Jefferson, “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 [The Rockfish Gap Report], from The University of Virginia (at: https://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefRock.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1).

39. Thomas Jefferson, “Report to the President and Directors of the Literary Fund,” The Avalon Project, October 7, 1822 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jeffrep3.asp).

40. In a letter on August 8, 1824, Jefferson said “I have undertaken to make out a catalogue of books for our library, being encouraged to it by the possession of a collection of yellowed catalogues; and, knowing no one capable to whom we could refer the task, it has been laborious far beyond my expectation, having already devoted 4 hours a day to it for upwards of two months and the whole day for some time past and not yet in sight of the end. It will enable us to judge what the object will cost. The chapter in which I am most at a loss is that of divinity, and knowing that in your early days you bestowed attention on this subject, I wish you could suggest to me any works really worthy of place in the catalogue.” Thomas Jefferson, “The Papers of Thomas Jefferson,” Library of Congress, letter to James Madison, August 8, 1824 (at: https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mtj1&fileName=mtj1page054.db&recNum=725&itemLink=/ammem/collections/jefferson_papers/mtjser1.html&linkText=7&tempFile=./temp/~ammem_kF9i&filecode=mtj&itemnum=1&ndocs=1).

41. James Madison, The Writings of James Madison, Gaillard Hunt, editor (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910), Vol. IX, pp. 203- 207, letter to Thomas Jefferson, September 10, 1824.

42. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XVI, p. 19, letter to Judge Augustus B. Woodward, March 24, 1824.

43. Thomas Jefferson, “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 [The Rockfish Gap Report], from The University of Virginia (at: https://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefRock.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1) called for this building and the stated purpose of religious worship in it; the subsequent reports Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, p. 394, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 2-3, 1820; Jefferson, Writings, Vol. XIX, pp. 411-412, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 7, 1822; and Jefferson, Writings, Vol. XIX, pp. 449-450, Board of Visitors, Minutes, October 4, 1824 reaffirmed that purpose.

44. Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XIX, pp. 449-450, “A Meeting of the Visitors of the University of Virginia on Monday the 4th of October, 1824.”

45. The Globe (Washington, D. C.), September 8, 1837, Vol. VII, No. 75, p. 2, Advertisement for the University of Virginia, printing a copy of a letter from the Rev. Mr. Tuston, the Chaplain of the University of Virginia to Richard Duffield, Esq. (originally printed in the Charlestown Free Press).

46. The Globe (Washington, D. C.), August 2, 1843, Vol. VIII, No. 42, p. 2, University of Virginia advertisement.

47. James Madison, “The Papers of James Madison,” Library of Congress, letter to Chapman Johnson, May 1, 1828 (at: https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mjm&fileName=22/mjm22.db&recNum=379&itemLink=D?mjm:13:./temp/~ammem_LjNU::).

48. Thomas Jefferson, The Life and Selected Writing of Thomas Jefferson, Adrienne Koch and Williams Peden, editors (New York: Random House, Inc., 1944), p. 697, letter to Thomas Cooper, March 13, 1820.

49. Encyclopedia of Religious Quotations, Frank Mead, editor (New Jersey: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1965), p. 50, quoting William Biederwolf.

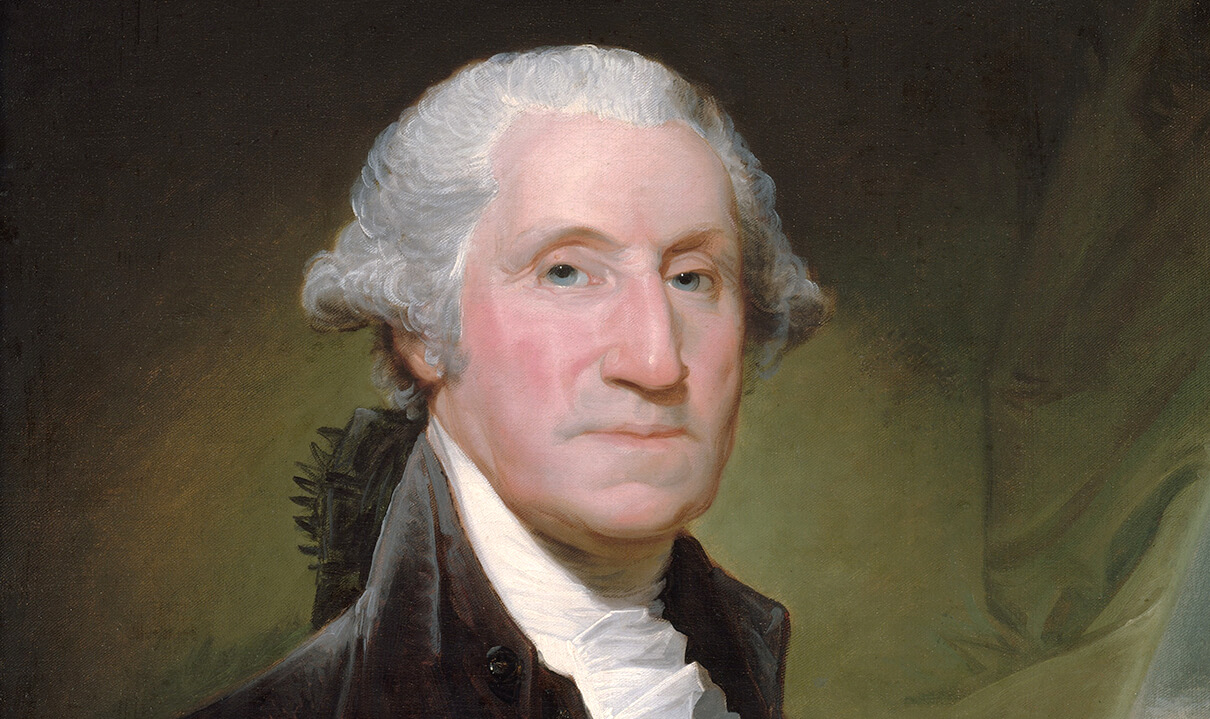

On receiving this news, Washington departed from Mt. Vernon and began his trek toward New York City, stopping first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit his mother, Mary¬ – the last time the two would see each other. Mary was eighty-two and suffering from incurable breast cancer. Mary parted with her son, giving him her blessings and offering him her prayers, telling him: “You will see me no more; my great age and the disease which is rapidly approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world. Go, George; fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to assign to you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and your mother’s blessing be with you always.”

On receiving this news, Washington departed from Mt. Vernon and began his trek toward New York City, stopping first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit his mother, Mary¬ – the last time the two would see each other. Mary was eighty-two and suffering from incurable breast cancer. Mary parted with her son, giving him her blessings and offering him her prayers, telling him: “You will see me no more; my great age and the disease which is rapidly approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world. Go, George; fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to assign to you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and your mother’s blessing be with you always.”