Aaron Bancroft (1755-1839) was a minute-man who served during the Revolution, fighting at Lexington and Bunker Hill. He graduated from Harvard in 1778 and was a missionary in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia for 3 years. Bancroft served as pastor of the Congregational Church in Worcester, MA (1785-1839). The following election sermon was preached in 801 in Massachusetts by Rev. Bancroft.

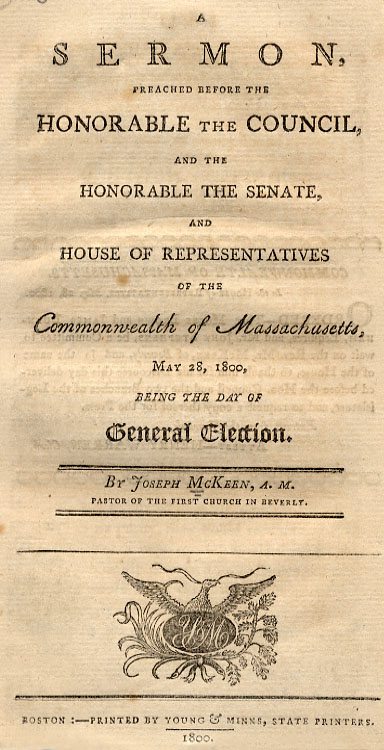

SERMON,

PREACHED BEFORE HIS EXCELLENCY

CALEB STRONG, Esq. Governour,

THE HONOURABLE THE

COUNCIL, SENATE,

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS,

MAY 27, 1801,

THE DAY OF

GENERAL ELECTION.

By AARON BANCROFT,

MINISTER OF THE SECOND CHURCH IN WORCESTER.

In SENATE, May 27, 1801.

ORDERED, That the hon. Elijah Brigham and John Treadwell, Esquires, be a Committee to wait on the Rev. Mr. Bancroft, and in the name of the Senate, thank him for the Sermon this day delivered by him, before his Excellency the Governor, the Hon. Council, and the two Branches of the General Court, and request of him a copy for the press.

GEORGE E. VAUGHAN, Clerk.

ELECTION SERMON.

ISAIAH LX. 21, 22.

Thy people shall be all righteous: they shall inherit the land forever; the branch of my planting, the work of my hands, that I may be glorified.

A little one shall become a thousand, and a small one a strong nation. I the Lord will hasten it in his time.

These verses contain a prophetic description of the influence and the effects of Christianity upon a community. They need not be exclusively applied to any one nation. It is the appointment of God—it is order of nature, that a course of good moral practice shall promote the strength and happiness of a nation. We see this truth illustrated in the pages of sacred and profane history: Our nation must furnish one more example to illustrate and enforce the divine maxim.

The passage before us I have chosen with a design to review the principles and habits, under the influence of which this Commonwealth has attained to its present state of population and strength, wealth and dignity; and to enforce the necessity of their preservation to our future welfare and prosperity.

The review will not be thought impertinent to the occasion, on which we are assembled. The commencement of a new century is an era, which invites to retrospection. We cannot too often recur to first principles. In the review, rulers will find the lines of their duty, and subjects the means of their happiness.

The settlement of America by Europeans is an event interesting to the man of piety and the philosopher. It was one of the boldest enterprises, which ever entered the human mind; and was prosecuted with an effort and constancy honorable to man. It originated neither in the lust of conquest nor the desire of gain. It was the love of civil and religious liberty, which animated our venerable ancestors to attempt the American colonization. They preferred freedom to ease, and the liberty to worship their God agreeably to the dictates of their consciences, to the affluence and splendor of the old world. They fled not from the wholesome restraints of government, but indignantly left a country, which denied them the exercise of the rights of Christians and of men.

The first emigrants to our shores were venerable for endowments, excellent in the human character, and conducive to the well-being of a community. Many of them possessed the essential attainments of solid literature: They lived under habitual impressions of a presiding Deity, and cherished a sacred regard to moral obligations. Their religion was an effectual principle of good practice through all the transactions of social and civil life. They felt the spirit of patriotism, and laid the foundation for a great and happy nation. They adopted the best measures to render their posterity the safe repository of the invaluable privileges, which, with infinite labour and hazard, they were enabled to transmit. While their security against the assault of their Indian neighbours, and the supply of their daily bread, were objects, on which to exercise all the energies of their minds, they opened temples for the worship of God; founded seminaries of literature; and established schools for the education of children.

The wisdom of their system was unfolded in the progress of their settlement. In families children received a religious education, and saw examples of piety and order. The surest principles of virtuous practice were impressed upon the infant mind, which grew with its growth, and were strengthened with its strength. With the incorporation of towns, schools were established upon a plan new to the world; supported at the public expense, they were alike open to the rich and the poor. Here the American youth were initiated into the elements of useful learning, were fitted for the business of society, and were prepared to support an independent and useful character. The general employment was the business originally assigned to man, the tillage of the ground, the natural exciter of sober habits.

Attendance upon the public institutions of the Sabbath was universal; and the adoration of divine perfections, the supplication of divine blessings, which formed the addresses to the throne of Deity; the unchangeable truths and duties of a religious and moral nature, which were explained and enforced in every sermon, tended, by their very reiteration, to keep alive deep impressions of the superintendence of God, a reverence for the divine character, and a view to the final issue of human action. These impressions were carried into all the transactions of the world.

The general influence of the above system was salutary to all the interests of society. The public opinion was formed to a sense of propriety of character and conduct. All orders felt the importance of a pure example. Irreligion and immorality were holden in universal disgrace; or, if the force of religion was not felt, deference to public sentiment constrained to decency of exterior behavior. The votaries of infidelity, impiety and vice dreaded the light of day, and sought darkness and concealment for their unhallowed communion. The evidence of these principles and practices in individuals was a bar to the attainment of every object of popularity and ambition. In this state of society, the love of applause, the desire of distinction, and every similar principle, combined their influence with motives of religion to preserve purity of general practice.

Elections to office by popular suffrage were conducted with purity and delicacy. Every imposition and interference were resented. The attempt of an individual to solicit suffrage was sure to defeat his ambitious wishes. A good moral character was considered an essential qualification in a candidate. Men of exemplary life were alone thought worthy of confidence.

A decent respect was paid to rulers, as the means to facilitate the object of their appointment. The public mind was not poisoned with groundless suspicions of evil designs in those, who managed their concerns. The traduction of public reputation was deemed a malignant vice. The watchful waited until trust was violated, and treacherous measures were adopted, before the confidence of people in their officers was attempted, by artful insinuations, to be destroyed, or the passions of the populace excited in opposition to the measures of government.

The business of government was a plain path, and led to the general good: It was easy, because it was managed without intrigue, upon system, and by uniform principles. The administrators of it were rewarded for their patriotic endeavours by the approbation and gratitude of their constituents.

The excellent judicial arrangements of the parent State were happily accommodated to our circumstances; and by our courts of justice, life, liberty, and property were secured. The execution of government in all its branches was aided by general opinions, customs, and manners favourable to the operation of wholesome laws; and by the sanction, which time always gives, in virtuous minds, to measures of wisdom and expedience.

The clergy of our country were denied that power, which ever inspires ambition, and excites, in eccesiasticks entrusted with it, the attempt to exercise spiritual domination over their fellow men. Those emoluments were not annexed to their offices, which furnish a temptation to luxury and dissipation: confined strictly to their profession, their influence was great and salutary.

A just apprehension of the encroachment of the parent government upon our colonial rights, kept in exercise a vigilant care of public liberty. The danger from the Indian tribes nourished a martial spirit, and habits of industry and sobriety gave nerve to the American character. If our countrymen possessed not the manners of a refined state of society, they were free from its dissimulation: If they were destitute of the blandishments of polished life, they were happily ignorant of the corruptions of old countries.

The American picture doubtless had its shade. With the purest piety, the spirit of religion in some instances, was intolerant; and a greater stress was often laid upon forms and ceremonies, than their nature and design will justify: but intolerance was the weakness of the age; and superstition is less dangerous than indifference to the concerns of religion. Our ancestors, religious in their principles, and chaste in their opinions, simple in their manners, and sober in their practices, rise to our view in the dignity of the human character. The good effects of their principles and habits appeared in the progress of our country from infancy to national manhood. Under the hand of her hardy sons, the wilderness blossomed as the rose; and the desert became a fruitful field. Her resources were increased with the exigencies that required them: She furnished characters to manage her important concerns; and numbered her proportion of men of science and wisdom in the roll of fame. Her growth was like the vigorous expansion of the human frame: The heart was found, and the head was healthy. There was no schism in the body. The head said not to the limbs of immediate action, I have no need of you; nor these to the head, we have no need of you; but whether one member suffered, all the members suffered with it; or one member were honoured, all the members rejoiced with it.

The strength of our countrymen was not to be estimated by their numbers; their principles and habits gave them a force superior to the physical powers of a despotick government. The influence of these was fully displayed, when our country assumed her place among the sovereign and independent nations of the earth. She was prepared in her genius and manners for a free, a republican form of government. Her patriots, educated in her own schools, discovered an acquaintance with political science, which had never been exceeded in the old world: they exhibited an acumen and energy of mind equal to the arduous post they were called to fill.

The habit of order was so effectually interwoven into the national character, that, in the suspension of the administration of justice, between the death of the colonial government, and the life of independence, great evils did not ensue. Our streets were not infested with robbers, nor our houses assaulted by thieves. When the publick mind was agitated by the hazard of objects the most interesting to man; when fear was awake to every impression of danger; when enthusiasm was excited as a necessary stimulus to endure the conflict; although suspicion was pointed against numbers among ourselves as hostile to the interests of the community, yet no individual through our Commonwealth, during the contest, lost his life by an act of popular violence. The men of our country, feeling the dignity of freemen, the lords of the soil, understood the worth of the rights, for which they contended; they were consistent in the measures of defence, and by their energies rose superior to the exertions of a kingdom powerful in the means of annoyance.

Independence acknowledged, we were enabled by the collected wisdom of the country to form, and on the result of due deliberation to adopt, “constitutions of government which combine liberty with order,” and the security of individual right with the necessary energy of the ruling power. The quiet and manly exercise of the highest freedom, which before had never been exercised by any people.

The united influence of the above causes has ripened a state of social order and happiness as near perfection, as the world has known. In our country, the prophetic description of our text has been verified. Our people have been righteous; by the benediction of God they have inherited the land, and risen superior to the thousand difficulties, which rendered the undertaking doubtful even to the sanguine mind. The branch planted by heaven, has been watered by streams of divine munificence; and our God, by it, has been glorified. A little number has become millions; and a weak band a strong nation: The Lord has accomplished it in his time.

Must the period that is now passed, in future, be remembered as the golden age of America? In a conformity to the customs, and in the imitation of the examples of our ancestors, we, their descendants, shall secure our social order and happiness. But is there no appearance, which darkens the prospect of the future glory and prosperity of our country? Is there no danger lest prosperity will intoxicate us? Have not too many fallen off from the principles and habits of their ancestors? Is not publick opinion in a degree corrupted? Are we not threatened with the loss of that spirit of religion, purity, and order, which thus far has been our union and strength, our honour and happiness? Is merit a security of reputation? Is patriotism sure of its reward in the approbation and gratitude of the community? Is not every candidate for public office made, through the virulence of party, the object of calumny and abuse? In the struggle of party for superiority, are there not given false representations of facts and measures? Under artful pretensions of patriotism, are not groundless insinuations brought into view, of dispositions and designs hostile to publick liberty and publick good? Must not every man, who consents to serve his country in publick life, expect that his character will be tortured upon the rack of jealousy; and even his good name be made to pass through the ordeal of slander and detraction?

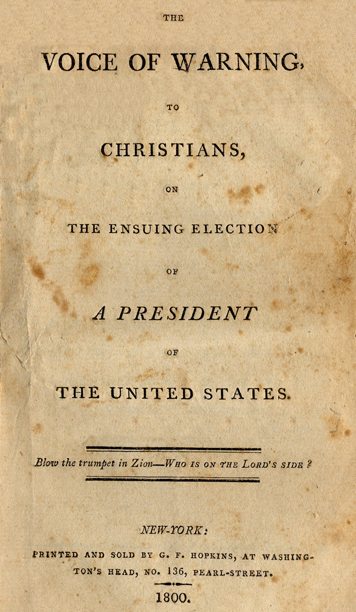

Another dark appearance in our political horizon, is a system of philosophy, which, under the spurious pretence of raising man to his perfectibility, destroys the fine feelings and ingenuous sensibilities of the human heart; which, while it dazzles the undiscerning mind with views of philanthropy, that have no distinct object, removes every restraint from the dissocial passions of human nature, and undermines every security of individual right. It degrades man from his rank, makes him the being of the moment, the sport of accident, and the absolute victim of death. The apostles of this philosophy disregard the wisest maxims of experience, and endeavour to introduce a national administration in politicks and morality, upon abstract principles. With the love of country and of man on their lips, they discover a disposition to demolish those pillars of society, which the world has holden sacred, and time proved to be necessary.

These sophists are not merely the growth of the present day; under other forms they have existed in past ages; and were ever found to be the enemies of the general order and social happiness. In the Roman story we find an order of the Senate to banish this class of men from the city of Rome, one hundred and sixty years before the birth of Christ. The reason assigned for their banishment gives a true character of the brethren of the order in modern times: “Because,” says the historian, “they were looked upon as dangerous talkers; who, while they reasoned on virtue, sapped its foundations, and were capable, by their own sophisms, of corrupting the simplicity of ancient morals, and of spreading among young people, opinions dangerous to their country.” 1 The revival of this philosophy in the present age, has been in the old world; but the corrupt passions of men render every country a soil too fertile in its growth: Wherever it spreads, it must prove destructive to the peace and happiness of human nature, and to the order and welfare of society.

Infidels of the last age generally acknowledged the moral government of the Deity, the immortality of the soul of man, and a future state of retribution. Although they aimed to deprive us of the more animating motives, and the superior hopes of revelation, they left us our God: they left us the system of moral obligation; natural religion was allowed its force. While men acted under the eye of Deity, and with a view to his approbation, we had some security for their probity and general good conduct; but, in the present age, Infidelity has assumed a more daring attitude, and uttered her blasphemies in a bolder tone. She has called in question the government and being of God. She has represented the whole universe, with all its orders of being, in all the variety of its works and harmony of its laws, as existing without an intelligent cause, or a moral end. These positions enervate all the principles, which bind society together, form the security of every valuable right, raise man to the dignity of his character, and direct his exertions to objects worthy the pursuit of a rational and accountable being. The disciples of the system have felt the spirit of proselytism; they have multiplied publications of a skeptical and blasphemous nature, which have too generally circulated in our land.

Experience will correct the error of sophists; but the evils, which operate this correction, may be incalculable. The work of mischief is much easier than that of good. The axe soon prostrates the tree, which time and nature have reared. The brand in a moment consumes the edifice, which years of labour and experience have erected. It is the same in the moral world. The insidious arts of the profligate may soon corrupt the pure mind of the youth, whose moral principles and sober habits were the result of the unwearied attention of a solicitous parent. The evil pens and contagious examples of some few characters of splendid talents and captivating address, may weaken the moral principles and corrupt the manners of a community, which required ages to establish, and which have formed the characters of successive generations of men. The publick opinion once corrupted, and the religious and moral habits of the people destroyed, the strong band of society is broken, and civil liberty is no more. We shall experience the decrepitude of national age, before, in the order of nature, we shall have attained to the full strength of national age, before, in the order of nature, we shall have attained to the full strength of national manhood. The forms of our government may remain, but its spirit will be fled; and some aspiring individual, like the artful Augustus, may adopt our forms to subserve his own ambition. Our nation will be rent by party, or we shall lie in the stupor of despotism. By our vices we shall forfeit the blessings of our God; our own doings will beset us about, and we shall suffer the miseries of impiety and wickedness, of faction and anarchy, of tyranny and oppression.

Had the founders of the Commonwealth established the plan of society upon a different basis, should we have attained our present state of respectability? Would not their successors have suffered by the weakness of the foundation, on which the superstructure was to be erected? Subsequent wisdom might have been insufficient to correct the errour of the first settlement. The future efforts of patriotism would have been ineffectual to raise the Commonwealth to its present state and dignity.

Try the supposition by the experience of those of our sister states, which were formed on different principles. We conceive, that we have maintained a superiority over them on many points of national importance; and we laudably wish to preserve our preeminence. In the above review we find the causes, and they are still operating, although, I fear, with weakened force. To the general information, the religious principles, the industrious and orderly habits, the sober and manly character of our people, we must attribute every superior excellence in our national features and condition. If we part with these for the worst of the maxims and practices of those states, whose social order has been less perfect, we shall sink below their level of worth and dignity.

It cannot be denied, that our whole system of religion and education has been attacked. When this is endangered, we may tremble, as the Israelites trembled when the ark of God was on the field of battle, or in the hands of the enemy. It is the palladium of our liberty, the security of our publick prosperity, and the foundations of our individual happiness.

Christianity assumes no other authority over the affairs of the world, than that, which arises from the influence of its doctrines and precepts upon the lives of men. Its connection with civil society results from its tendency to enrich the heart with every virtue which adorns human nature, or increases social happiness; and to enforce the duties of rulers and subjects by sanctions, which the occurrences of this world cannot weaken. This influence is infinitely important.

The experiment of conducting the concerns of civil government without the aid of religion, has recently been made in the old world, and reason is abashed, and humanity blushes at the scenes of oppression and cruelty that ensued. Religion legitimates every subordinate principle of action: It ennobles ambition, by directing it to its proper object: It renders the love of same safe and laudable, by making it the motive of salutary conduct: It gives to benevolence its active force, by the assurance of its ultimate reward. When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice; but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn. Religion, in all its aspects, is favourable to liberty: It restrains the turbulent passions of men, renders them submissive to good laws, and, in the disposition of their minds, prepares them for the utmost extent of freedom. But when moral restraints are removed; when dissocial passions have uncontrolled license; when the spirit of party and faction is prevalent, energy of government becomes necessary. Unable to govern itself, such a people requires severity in the ruling power, and in some form it will arise.

The situation of the United States is daily changing. Commerce has opened all her sources of wealth to our enterprising merchants; and the luxuries, which the increase of riches has introduced, threaten to contaminate our purity and enervate our strength. The political state of Europe has flung many foreigners among us, whose genius and habits will not amalgamate with the American character. With this unhallowed mixture, our national manners and character are in danger of being corrupted.

The resources of our country are abundant, if the minds of our people can be kept fixed to their interests, and their patriotism and virtue be preserved. With these guards upon our nation, we need not fear foreign powers. If we fall, it will be by our own vices. If we must run the race of impiety and folly, of party and faction, of dissipation and vice, in which all Republicks have preceded us, let the wise and good unite their energies to procrastinate the catastrophe, and to the utmost, continue the reign of virtue and happiness.

In this view, a sacred and important duty devolves upon men in conspicuous stations, and of influential characters, by their example to encourage attention to institutions, which have proved salutary to our country. The force of example is great. The example of those, who move in elevated spheres, and possess commanding talents, has superior influence. Men of this description possess high means of publick good; motives of religion and patriotism conspire to induce their exercise. They may exert themselves free of the prejudice, which often attaches itself to characters, whose professional business is moral instruction and persuasion. They will not be suspected of interested motives in the support of a system of religion, by which they gain their bread, and acquire an influence over the minds of their fellow-men. Their endeavours will probably have effect upon many, who are prejudiced against the common methods of instruction and improvement. These will certainly be effectual with all, who are governed by the fashion of the day, and implicitly follow the direction given by the great and splendid.

The association of distinguished persons in England, to discountenance infidelity, irreligion, and immorality; and to encourage the observance of the Christian Sabbath, attention to the institutions of the gospel, and the general practices of piety and virtue, is worthy the imitation of similar characters in our country.

The political opinions of the speaker will be discovered by the tenour of his observations: But he addresses himself to no party. He disavows the spirit. Of the evils which menace our peace, all complain: In the preservation of the principles and habits recommended, all discerning patriots will be united. He has not the presumption to dictate to the rulers of the Commonwealth, the measures of their publick conduct: Yet they will permit him to suggest the importance of an adherence to a system which has been productive of so much publick good. Religion, as a transaction between God and the souls of men, is too sacred for human regulation. Civil government may not intermeddle with this holy subject. But it clearly falls within the province of a Christian legislature, to support institutions, which facilitate the instruction of people in the truths and duties of religion, which are the means to give efficacy to the precepts of the gospel, and are calculated to instill the spirit of morality and order into the minds of the community. The oath of office makes this the duty of our Legislature, by the third article of the Bill of Rights. The denial of the being or government of God, blasphemy, and the derision of moral obligation, destroys the solemnity and use of oaths, and weakens the principles, on which the administration of justice and the peace and order of society are suspended; laws, therefore, against these crimes, the freest governments have conceived to be within their powers, and have enacted. To regulate the dissocial affections, to restrain the licentious passions of human nature, and to render “man mild and sociable to man,” is one essential end of civil government. Errours of speculation, which sap not the foundation of society, must be left, for their correction, to the natural force of truth. Many errours in practice we must leave to the operation of moral causes; suffer their endurance until a remedy shall be found in their consequences; until the misery they produce shall correct them. If profligate publications cannot be prevented, their deleterious influence may be counteracted by habits of wise reflection and sober practice. As the means of this important end, government will extend its patronage to our university, colleges, and schools. On these institutions are dependant our prospects for characters to fill the publick stations of society, and to defend our country from the insidious attacks of the disciples of infidelity and vice.

The general education of youth is a subject of as high importance as can occupy the mind of the patriot or the Christian. To render them the worthy heirs of the invaluable inheritance, which we hope to transmit, they must understand the nature of a free government; distinguish social order from anarchy; liberty from licentiousness; the freedom of law from the unrestrained freedom of the savage. They should be inspired with moral principles, as a security against the seductions of a country, rapidly increasing in the means of dissipation and voluptuousness: by habits of piety and virtue, their minds should be armed to repel the assaults of infidelity and libertinism.

The speaker wishes, with deference to suggest, whether some plan might not be grafted into our general system of education, to disseminate the political information necessary to a republican government; and to secure the rising generation from that spirit of innovation, and rage for change, which endanger the primary principles of good order. Care will be taken, that our youth fall not into the hands of instructors of profligate characters, and abandoned principles. The purity of elections will be guarded, and encouragement given to the wise and faithful exercise of the rights of suffrage; that our government may not become corrupt in its first operation. By measures directed to these important objects, our civil rulers will be the nursing fathers of the Christian church, and the guardians of the manners and habits of the community.

The large majority, by which his Excellency is re-elected to the chief seat of government, evidences the approbation of the Commonwealth, of his past services, in this elevated and responsible office. Unanimity, at this day, was not an object of expectation. It is an honourable testimonial of personal merit, that his support has been the greatest where his private character was best known. The unanimous suffrage of those, who were conversant with his walks in social life, must be grateful to the feelings of his Excellency. Confident, that he will lend the united force of his authority and example, to support the institutions of religion, and to preserve the purity of publick morals; that he will execute his trust in righteousness, and with an impartial view to the general good, we wish him the guidance of heaven. May the measures of his administration be applauded by the wise, and approved by the just: May he possess the increasing confidence of his country, and obtain the reward of his God!

The present state of politicks renders the publick service of the two Branches of the Legislature arduous and difficult. They will be watched with critical attention. Their best designs may be attributed to impure motives, and their wisest measures censured. Under these circumstances, worldly principles of action would fail; but the man, who looks within himself for the rule of his publick conduct, will never want support. In the testimony of his heart to the purity of his intentions and the rectitude of his actions, he will find a reward. He will be strengthened to persevere in the path of patriotism and virtue, from a regard to the approbation of Him, who is higher than the highest, whose eyes survey the children of men, and who requires that which is altogether just. Although they now fit as gods, they will reflect, that they must die as men, and give account like one of the people. May wisdom direct their deliberations, and the benediction of heaven render the measures of their adoption beneficial to their country!

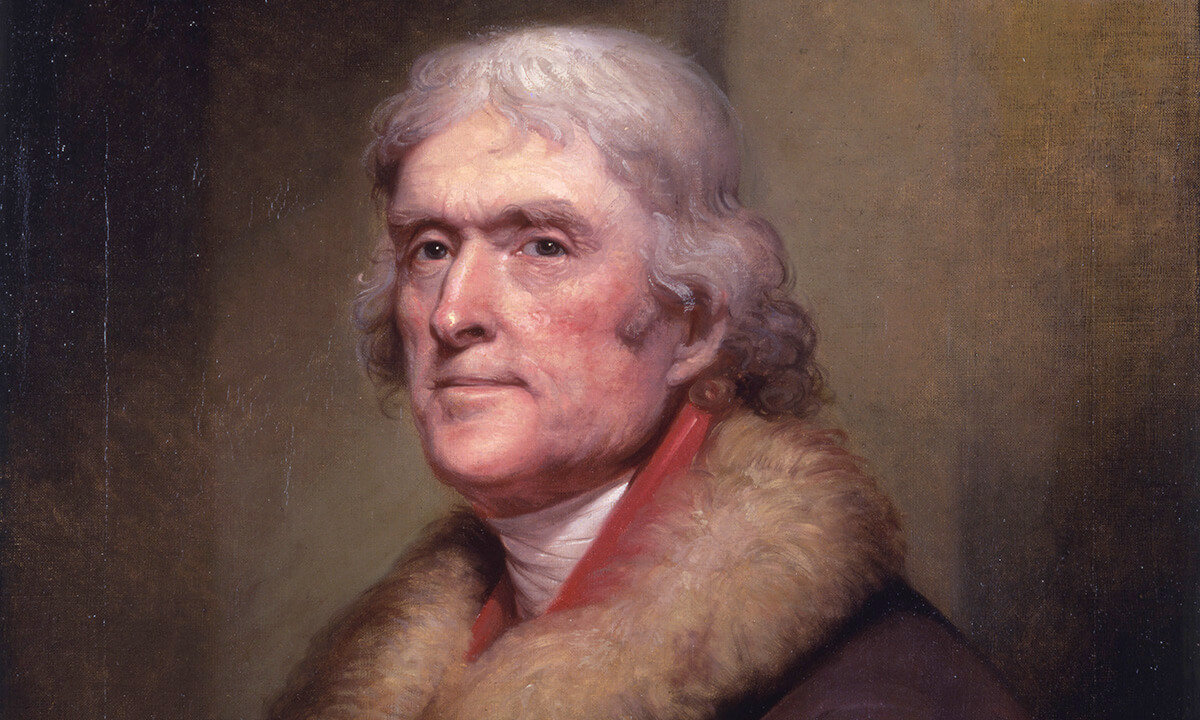

To pass unnoticed, on this occasion, the general government of the United States, might be deemed critical omission.

It has been our happiness, that the men placed at the head of the government, were distinguished as well for their piety, as for their political wisdom. Its administration has accorded with the characteristic maxims of our own Commonwealth. Never was a people under higher obligations to a government, than we are to that of the Union. At its organization, the country was embarrassed in every national operation. In each department, the administration was without a precedent: It had new paths to explore, and first principles to adopt. The state of Europe rendered its connexions with foreign nations critical and hazardous. The convulsions of that country soon reached us: We were annoyed by the maritime force of the powers at war: We were the objects of their diplomatick artifice and intrigue: The honest prejudices of our own countrymen aided the interested designs of one of the belligerent powers, and made the business of our rulers the more delicate and laborious. War, like a portentous cloud, hung over our land, and threatened us with all its evils. Under these perplexing circumstances, the administration firmly took the ground of neutrality, and with moderation exercised its rights. It sacredly preserved publick faith; impartially executed national justice and in this way secured us the blessings of peace and tranquility. While the stablest pillars of old governments, and the long established order of society were convulsed, under the auspices of the general government, the resources of our country were called into action; publick credit was established; individual right secured; and the property of the nation doubled. As the price of these blessings, we have paid but one direct tax. Is not a debt of gratitude due to those, who, under God, have been the instruments of this unexampled prosperity? That no mistakes have been committed in the management of our national concerns, is not presumed. Infallibility is not the portion of man: But experience, the best test of the wisdom of publick measures, has given its sanction to those of the federal administration.

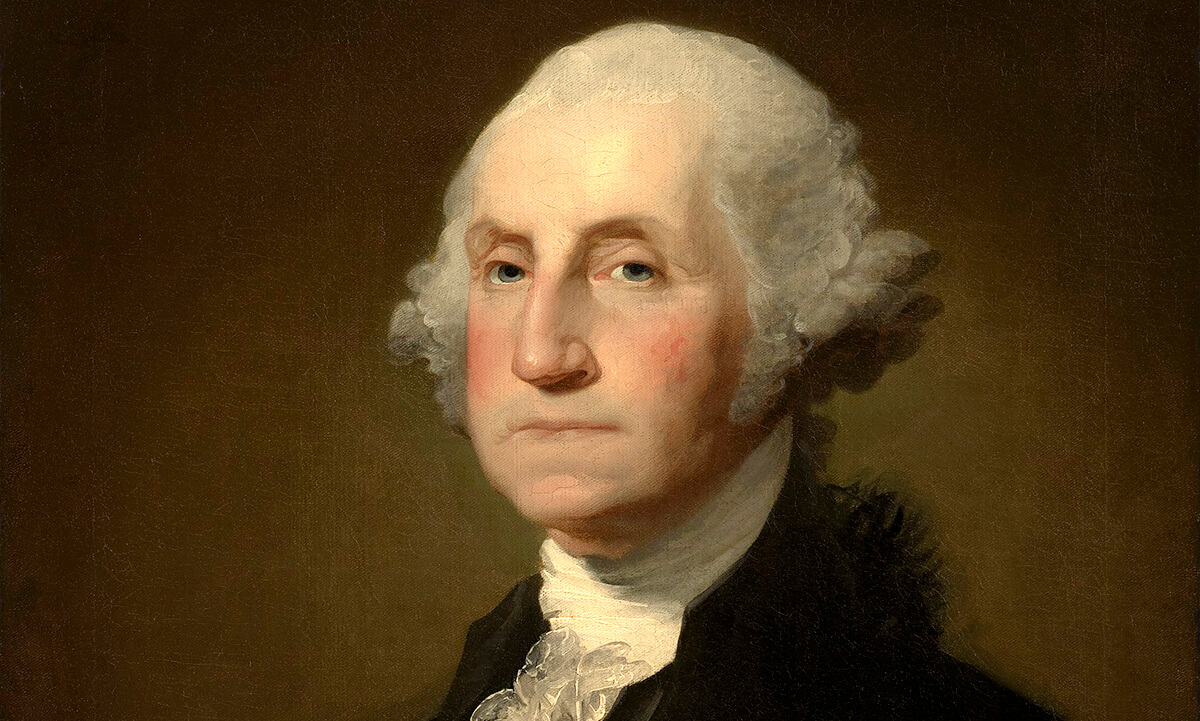

Our own venerable patriot, who has now retired to private life, to enjoy dignity with ease, demands the grateful acknowledgements of his signal services. He was among the first to vindicate the invaded rights of his country. He was a primary agent in the establishment of independence; and the confidential minister of the publick during the revolutionary war. By his diplomatick negotiations, he conciliated the friendship of some respectable nations in Europe to our infant Republick, and obtained a loan of money, when our exigencies were the greatest. Under his auspices, as the federal head, our country has probably passed the crisis of danger from the commotions of Europe. His active life has been devoted to publick employment, and through all his stations of trust and responsibility, his integrity and patriotism have been without a stain. Difference of opinion on questions of high national moment, may, for the present, prevent his worth from being duly appreciated; but the impartial historian will do justice to his merits: In future time, the State which gave him birth will derive a lustre from his name.

The return of this anniversary is calculated to animate the minds of all, who attend upon it. The human heart must be enobled by the reflection, that our governours and legislators are raised to office by our own suffrages. To behold them assembled in a body, by their united wisdom, to consult the welfare, and transact the business, of the Commonwealth, is a sight to give joy to every lover of liberty and of country. What impressions would this sight make on the reflecting minds of those, who groan in the chains of despotism? To behold this venerable body around the altar of God, to implore divine wisdom in their deliberations, and the blessing of Heaven upon the measures of their future adoption, must raise every soul in devout gratitude to the original author of all mercies.

Happy America, didst thou know thine happiness! Would to God, that all nations of the earth might annually pass in review before thee, to teach thee the excellence of thy situation, and to inspire thee with a conduct necessary to perpetuate thine advantages! Search the globe, and where can be found, a people, among whom, civil and religious privileges are more perfectly enjoyed? What people of the earth may more justly be attached to their country, than those of Columbia? Where may the spirit of patriotism be cherished with brighter prospects? O! that I could speak with an energy to reach the hearts, and animate the practices, of all the citizens of the United States. Our governments, with all their attendant blessings, are bottomed on the broad basis of publick opinion; and in their support, require the individual exertions of our countrymen.

Can prosperity never content the human mind? Having obtained the highest object of freedom, do we desire a change? From a jealousy that our rulers may do us evil, shall we deprive them of the means to do us good? Shall we leave the protecting arm of Deity, to become the sport of atheistical chance and accident? Shall we turn from the light of revelation to follow the blind guides of infidelity, that we may be left in dark and desolate regions, where there is no path to direct our steps, no object to reward our labours? Shall we give up the enobling hope of immortality, to become like the brute, the victim of perpetual sleep? Shall we part with the maxims of our venerable ancestors, which time has proved to be wise, for a spirit of innovation, which nothing sacred or profane can restrain? Shall we part with the certain blessings of civil freedom and social order, for the fanaticism of ideal liberty and equality, which the nature of man, and his condition of action make it impossible to realize?

God grant, that the spirit of our text may possess the hearts and regulate the lives of our countrymen. Our people being all righteous, the work of righteousness will be peace; and the effect of righteousness, quietness and security forever. Our rulers being just, ruling in the fear of God, they will be to us like the morning when the sun riseth, even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth by clear shining after rain.

Under this spirit, the general and state governments will operate on each other like the laws of cohesion and attraction, in nature; like the heavenly bodies, they will revolve in harmony, and from their combined influence we shall derive national prosperity and individual security. We, the branch which God has planted, shall inherit the land to His glory. With the steady progress of time, we shall advance towards national perfection, for our God will bless us.

Endnotes

1 Suctonius in his book of Rhetoricians.

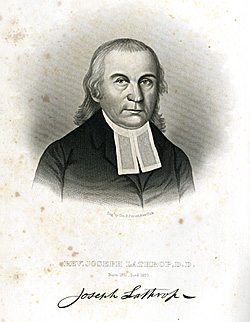

(1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography: