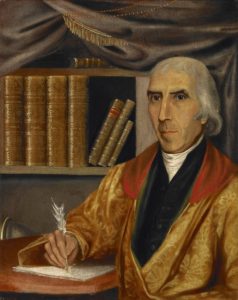

Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826) Biography:

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Morse also held a lifelong interest in education. In fact, shortly after his graduation in 1783, he started a school for young ladies. As an avid student of geography, he published America’s very first geography textbook, becoming known as the “Father of American Geography,” and he also published an historical work on the American Revolution. He was part of the Massachusetts Historical Society and a member in numerous other literary and scientific societies.

Morse also had a keen interest in the condition of Native Americans, and in 1820, US Secretary of War John C. Calhoun appointed him to investigate Native tribes in an effort to help improve their circumstances (his findings were published in 1822). His son was Samuel F. B. Morse, who invented the telegraph and developed the Morse Code.

A

SERMON

DELIVERED BEFORE

THE

ANCIENT & HONOURABLE ARTILLERY COMPANY,

In Boston, June 6, 1803,

BEING THE

ANNIVERSARY

OF THEIR

ELECTION OF OFFICERS.

By JEDIDIAH MORSE, D. D.

Minister of the Congregational Church in Charlestown.

“Ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls.”

The Prophet Jeremiah.

ARTILLERY SERMON.

PSALM LXXVII, 5.

I have considered the days of old, the years of ancient times.

JEHOVAH in governing that universe, which he has created, is uniform in all the operations of his administration. His throne is established in righteousness. All his ways are just and equal. With him there is no variableness, neither shadow of turning. What has happened in former ages, will happen again under similar circumstances. Like causes invariably produce like effects. For these reasons wise men will ever highly value and diligently consult faithful history. It is a mirror, in which nations and smaller communities, acquainted with their own civil and religious state and character, may perceive, what they have to hope or to fear from the righteous Governor and Judge of the world. From it they may learn, what causes have conduced to exalt nations to the favor and protection of God; and what character and conduct of a people have exposed them to his displeasure, and operated their final destruction. It will therefore be our wisdom with the psalmist, to “consider the days of old, the years of ancient times.” In particular it is our duty to examine the history of our own nation, to trace effects, which fall under our notice, to their legitimate causes, and to profit by the wisdom and experience of our sage and pious ancestors.

From the candor of this respectable audience I will hope that I shall not be considered, as deficient in respect for the remaining portion of the United States, or as intending to make any invidious distinction, if in this occasional discourse I confine my observations chiefly to New England. The history of this division of the United States, which is probably better known from its earliest settlement than that of any other portion of the globe, is marked with some peculiar facts and circumstances, recurrence to which may not be deemed unsuitable to this anniversary.

The settlement of New England was a regular, though remote effect of the grand Protestant Reformation. This purifying fire, kindled first in Germany about the year 1517 by the instrumentality of Luther and Melancton, soon spread through Switzerland and Geneva under the direction of Zuinglius and Calvin; and afterward, in the reign of Henry the 8th, under the preaching of Cranmer, Ridley, Latimer, and the famous John Knox, pervaded the native country of our venerable ancestors. 1

Of those in England, who appeared in favor of the Reformation, many, constrained by the torrent against popery to disguise their real opinions, were in heart papists, and retained the ‘old leaven.’ Others, influenced by political views, heartily joined in casting off the papal yoke, but were unwilling to relinquish the rites and ceremonies of the Romish worship. Some from a mistaken and timid policy advocated a gradual reform in hope, that by tolerating some things, which they disapproved, prejudices would be removed, and proselytes to the Reformation be multiplied. This accommodating policy to reconcile Christ and Belial, truth and error, has ever, when practiced, produced most pernicious effects both in church and state. There was still another class of the reformed, who, possessing more honesty, discernment, Christian zeal, and independence, boldly appealed to “the law and to the testimony,” and the only standard of religious truth. They openly renounced all the dogmas of popery, and all human impositions, asserted liberty of conscience in matters of faith, were enemies to ecclesiastical tyranny, to the splendor and magnificence of the Romish worship, and strenuous advocates of Scripture purity and simplicity, and hence acquired for themselves the distinctive name of Puritans. From these heroic disciples of Christ our ancestors descended; and they were worthy of their descent. They were men indeed of like passions with others; they had their imperfections, and they partook in a degree of the errors and delusions, peculiar to the times and circumstances, in which they lived. But these were only as spots in the sun; so resplendent were their virtues, that their blemishes are scarcely visible but to the telescopic eye of modern philosophism.

At the period, when the settlement of New England commenced, the parent country was in an advanced stage of improvement. The darkness and ignorance of popery had in a good degree been dissipated by the light of the Reformation, and the useful sciences began to be cultivated with success. It was at the same time in such a state of agitation from religious intolerance and persecution, as was calculated to force into exile the most wholesome members of the community. Accordingly the first settlers of New England were among the best and most enlightened people of the age, in which they lived. In servant Christian piety, independence of soul, and boldness of enterprise; in firmness to encounter danger, in patience to endure trials and hardships most severe, in wisdom to devise, and ability, energy, and perseverance to execute plans for the honor, safety, and lasting happiness of their posterity, they have been exceeded by no body of people in any age of the world. It is but justice to class the mothers with the fathers of New England. Each in their station equally excelled, and have an equal claim to the veneration and esteem of their posterity.

In evidence of the truth of this high character of our ancestors I adduce the testimony of that great and good man Mr. W. Stoughton, first a preacher and afterward promoted to the command of the Province of Massachusetts. He was cotemporary with these worthies, and declared, what he knew from personal observation. In his Election Sermon of 1668 he says, “As for extraction and descent, if we be considered, as a posterity, to what parents and predecessors, may we the most of us look back? As to New England, what glorious things might here be spoken unto the praise of free grace, and to justify the Lord’s expectations upon this ground? Oh what were the open professions of the Lord’s people, that first entered this wilderness? How did our fathers entertain the Gospel, and all the pure institutions thereof, and those liberties, which they brought over? What was their pitch of brotherly love, of their zeal for God and his ways, and against ways destructive of truth and holiness? What was their humility, their mortification, their exemplariness? How much of ‘holiness to the Lord’ was written upon all their ways and transactions? God sifted a whole nation, that he might send choice grain over into this wilderness.” Again, he asks, “Those, that have gone before us in the cause of God here, who and what were they? Certainly choice and picked ones, whom he eminently prepared, and trained up, and qualified for this service. They were worthies, men of singular accomplishments, and of long experience.” 2

“There were among them,” says another competent witness, 3 “many plants of renown, trees of righteousness, some of the choicest in the whole garden of Christ; and their transplantation from Britain to New England did but add to their beauty, verdure, and refinement. They flourished in this foil, and multiplied, and brought forth abundantly the fruits of righteousness.” They were “a noble army of confessors,” educated in the school of patience, purified in the furnace of affliction, and, finding no rest at home, fought an asylum abroad, and were directed by that “wisdom, which is first pure, then peaceable,” to this “land, which God had espied for them.” They were Abrahams, the friends of God, and their lot in life, in many particulars, bore a striking resemblance to his. The kindred and countrymen of this father of the faithful were given up to idolatry and superstition. Their example was contagious. The pure worship of God could not in safety be maintained. Liberty of conscience was denied. The true religion could be preserved only by emigration of the few, who remained uncorrupted, into a foreign country. Under these circumstances God called Abraham “to go out into a place, which he should after receive for an inheritance,” there to establish and maintain in its purity the worship of the true God. By faith he obeyed the call, and “took Sarai his wife, and Lot his brother’s son, and all the substance, that he had gathered, and the souls, that they had gotten in Haran, and went forth,” ignorant of the way, “to go into the land of Canaan,” an unknown country; but confiding in God, as their guide, they persevered, and “into the land of Canaan they came.” Almost literally the same may be said of our progenitors. Indeed, “if there has been any people in the world, whose general history runs parallel with that” of the descendants of Abraham, “it is the people of New England.” 4

Such were our ancestors; and such the circumstances, under which they commenced the settlement of this portion of the globe.

A country like New England rough, healthful, pleasant, calling for that portion of labour and industry, which conduces in the highest degree to soundness of body and purity of mind, abounding in all the comforts of life, planted under the special auspices of heaven, and by such men, we should naturally conclude, would become a second Canaan, a favored land. From feed so pure, we should expect a fair and abundant harvest of good fruits. Accordingly in no inconsiderable degree have the following promises, made to Abraham, been fulfilled to the founders of New England: “I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great, and thou shalt be a blessing; and I will bless them, that bless thee; and curse him that curseth thee.”

The little company who first went out like Abraham and his family “not knowing whither they went,” has increased into a very numerous people. Hardships incredible they were indeed called to endure in the infancy of the colony; but God had compassion on them, for his covenant’s sake, and permitted not the sword of the wilderness to devour, nor cold, nor famine to destroy, nor fatal sickness to make the land desolate. In all their afflictions he was afflicted, and the angel of his presence saved them. In his love and his pity he redeemed them , and he bare them, and carried them all the days of old. The righteous saw it, and were glad. Iniquity stopped her mouth; or her curse was turned into a blessing. The wrath of man praised God; the remainder thereof he restrained. The Lord was their strength, their fortress, their high tower, and deliverer; their shield, in whom they trusted. He taught their hands to war and their fingers to fight, and gave them victory over their enemies. The beauty of the Lord was upon his people, and he established and prospered the work of their hands. He blessed them in the city and in the field. Zebulon rejoiced in his going out, and Issachar in his tents.

As the righteous Governor of the world ever accomplishes all events by the fittest means; it may be profitable here to inquire, by what means New England rose in opposition to obstacles so formidable, as were opposed in her way, from small beginnings to so high a degree of respectability and prosperity. What causes have operated to secure for her inhabitants so singular a portion of the blessings of heaven?

Doubtless the early and continued increase and prosperity of the people of New England must be considered, as the gracious reward of their singular piety and wisdom; and the precious fruit of those excellent religious, civil, literary, and military institutions, which their piety and wisdom prompted and enabled them early to establish, and afterward to maintain.

The first planters of New England, it has been remarked, were not like the Israelites, who went up out of Egypt, a mixed multitude, “a promiscuous assemblage; they were in general of uniform character, agreeing in the most excellent qualities and principles. They were Christians very much of the primitive stamp.” There was nothing indeed in the nature and object of the enterprise, in which they engaged, to tempt men of a different character to quit their native country, and to brave the dangers of crossing a wide ocean, and the hardships of settling a wilderness. It promised to honors to the ambitious, to pleasures to the voluptuary , no gain to the avaricious. It opened no field of action to wicked men of any class. The main object of the hazardous enterprise being to establish and enjoy the pure religion of the gospel, the great body of those, who engaged in it, were men, “who felt the power of that faith, which worketh by love, which overcometh the world, and is the substance of things hoped for, and the evidence of things not seen.” The few, who mingled with them from sinister motives, or “came hither upon sudden and undigested grounds,” soon returned disheartened and in disgust to their native country, leaving behind them “a shining collection of sincere professors, who enlivened and animated each other in following after holiness by the reciprocal influences of an alluring example.” 5

Anxious to perpetuate for themselves and their posterity the liberty and privileges, both religious and civil, which they enjoyed, they fought, and received direction from heaven concerning the best means for this end. In every plantation their first care was to establish a church, and settle a minister, that the worship of God might be regularly and decently performed, and the people instructed in the doctrines and duties of the Christian religion. Knowing that the declension of piety and the corruption of morals are invariable consequences of neglect and profanation of the Christian Sabbath, they regarded, and by laws protected, this sacred day with uncommon strictness.

When the churches were multiplied and scattered over a considerable extent of country, in order to preserve unity and purity of faith in the bonds of love and peace, they assembled in Synod by their delegates, and framed and adopted a “Platform of church discipline.” From this instrument of union, which long continued to regulate all ecclesiastical proceedings, and which even now is appealed to, as an authority of weight, great good has resulted to the Newengland churches. We should readily suppose this from the characters, which formed it. According to the joint and dying testimony of the venerable and aged Higginson and Hubbard, who in the year 1701, had lived, one of them sixty, the other seventy years in Newengland, the framers of this platform “were men of great renown in the nation, whence the Laudean persecution exiled them. Their learning, their holiness, their gravity struck all men, that knew them, with admiration. They were Timothies in their houses, Chrysostoms in their pulpits, Augustines in disputation. The prayers, the studies, the humble inquiries, with which they fought after the mind of God, were as likely to prosper, as any men’s upon earth. And the sufferings wherein they were confessors for the name and truth of the Lord Jesus Christ, add to the arguments which would persuade us that our gracious Lord would reward and honor them with communicating much of his truth to them. The famous Brightman had foretold, Clariorem lucem adhuc solitude dabit; “God would yet reveal more of the true church state to some of his faithful servants, whom he would send into a wilderness, that he might there have communion with them.” And it was eminently accomplished in what was done for and by the men of God, who first erected churches for him in this American wilderness.” 6

Aware of the necessity of civil government to secure the welfare of the infant colony, the first adventurers, before they landed at Plymouth, formed themselves into a body politic, under a solemn covenant, which they made the basis of their government. By this civil compact they were empowered to “enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices, from time to time as might be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony.” The foundation of their civil polity being thus laid, they religiously selected their wisest and best men to erect the superstructure. 7 Believing that “he, who ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God,” a hater of covetousness, a terror to evil doers, and a praise to them that do well, “they promoted none, but men of this character, to manage the affairs of government. To infidel despisers of religion and its ordinances, to unprincipled demagogues, to sycophantic declaimers, and office seekers, to men in general of corrupt principles and morals, they gave no countenance. They considered and treated the few of this class, who ventured into New England, as the bane of the commonwealth. Abundant testimony of the truth of what I have now stated might be adduced from our history; you will be satisfied, I presume, with that of the venerable Mitchel, Oaks, Prince, and Shepard, in their Election Sermons. In 1667 Mr. Mitchel observes, “This is the 37th year current with the Massachusetts colony, that God hath given them godly magistrate.” He adds, “The sun does not shine on a happier people, than they are in regard of his mercy.”

Six years after this Mr. Oaks testifies, as follows, “Many and wonderful are the favors and privileges, which the Lord your God hath conferred upon you. As to your civil government you have had Moses, men I mean of the same spirit, to lead and go before you. The Lord hath not given children to be your leaders, but pious, faithful, prudent magistrates, men in wisdom and understanding; men of Nehemiah’s spirit, that fought not themselves, but sincerely designed the good, and consulted the welfare and prosperity of these plantations. Good magistrates, good laws, and the vigorous execution of them, have been the privilege and glory of New England, wherein you have been advanced above most of the nations of the earth.”

In 1730 Mr. Prince confirmed the testimony of his predecessors: Speaking of the civil fathers of New England, who had gone before them, he says, 8 “They were mostly men of good estates and families, of liberal education, and of large experience; but they chiefly excelled in piety to God, in zeal for the purity of his worship, reverence for his glorious name and strict observance of his holy Sabbaths; in their respect and maintenance of an unblemished ministry; the spread of knowledge, learning, good order, and quiet through the land, a reign of righteousness, and the welfare of this people; and the making and executing wholesome laws for all these blessed ends.”

At that pure and pious period of our commonwealth there was a happy concurrence between civil and ecclesiastical leaders in promoting religion. “Then” (says Mr. Shepard, 9 one of my worthy predecessors,” “might be seen magistrates and magistrates upon the seat of justice, cemented together for the advancement of the kingdom of Christ in this wilderness. Then might be seen magistrates and ministers together in way of advice: ministers and ministers cleaving together in way of communion: ministers and their respective congregations together in way of prayer and holy worship: churches and churches together in way of consultation, by greater and lesser synods; magistrates and ministers and their people together, uniting hands and hearts in the common cause, breathing a public spirit, and conspiring with holy zeal and vigor, to advance the kingdom of Christ.” The excellent rulers of that day “united with their pastors in consultations and endeavors for the advancement and preservation of religion, and the privileges, peace, and order of the churches. By their grave and prudent carriage they happily preserved a veneration for their persons and authority among the people; and yet carefully protected them in the full enjoyment of their precious liberties.” 10

Blessed be the God of our fathers, who hath not forsaken us. Such characters, as we have now described, men of like excellent spirit, still govern in our favored New England. They are consoling evidences of our remaining health, previous guardians of our dearest privileges, the salt of the earth; pledges of the continued favor and protection of heaven. For such rulers we most fervently wish long life, increasing influence, and the blessing of God Almighty.

The doctrines, that “ignorance is the mother of devotion,” that human learning is not a requisite qualification in the ministers of religion, nor yet in those, who govern, and legislate for the commonwealth, were not the doctrines of our fathers. They had no belief, that the fear of God could be preserved, or that the rights of citizens would be secure, should the lowest of the people be advanced to the priesthood, or promoted to make and execute the laws of the commonwealth. They considered learning, as the handmaid of true religion and rational liberty; and that neither could flourish, or long exist, without her aid. Accordingly, prompted by their piety, and directed by their superior wisdom, they established schools on a plan new, liberal, and useful, far beyond any before or since invented; a plan, which, providing equally for the poor and the rich, who mingled in the same school, was admirably calculated to draw into notice and use, genius and worth, which, but for this device, might have been forever concealed in the obscure abodes of poverty. By means of this excellent institution of free schools, sufficient of itself to immortalize the memories of our sage progenitors, thousands have been advanced from the humblest sphere of life, and introduced upon the public stage, where they have acted parts in behalf of the state, and of the church, highly honorable to themselves and useful to their fellow citizens.

Sixteen years 11 only after the first landing of our fathers at Plymouth, and within less than eight after the first planting of the Massachusetts colony, while they were yet without wealth, in a wilderness, surrounded by a savage and faithless race, they laid the foundation of Harvard College. So highly did they value the advantages of liberal education. This seminary, nurtured by the prayers of its pious founders and friends, and the liberal benefactions of the legislature and of private individuals, greatly flourished, and diffused its benign influence through New England. From this ancient institution, respectable and pleasant in our eyes, early established “to enlighten and rejoice our land,” have proceeded some of the most brilliant and useful ornaments of New England, both in church and state. Shall not the example of those excellent men, who established, and fostered, and prayed for this institution; shall not the rich harvest of blessings, which it has yielded to our country, secure for it still the affection and patronage of our civil fathers? So shall it continue first, as she is the eldest, among her sisters, the beauty of New England, and the mother of illustrious worthies for ages and ages to come.

On all the glory of New England God was pleased to create a defense by inspiring the people in general with a brave, intrepid spirit, suited to their perilous circumstances, and particularly by leading them early to establish that very useful and honorable military association, whose anniversary we now religiously celebrate in the house of God; to whose history, agreeably to their request, I shall now invite your attention.

Our sagacious forefathers laid deep and broad foundations for the happiness of their posterity. They seem to have left nothing undone, which they could do, to secure the grand object of their migration to this country. Pacific and inoffensive as they were in their principles and conduct; fair and honorable as were their treaties and traffic with their Indian neighbors; they were still exposed to their insidious and hostile attacks. To their religious, civil, and literary institutions, it therefore seemed necessary to add one of a military kind, which might serve, as a school, in which the knowledge of this important art might be advantageously cultivated, and as a nursery for the formation of officers and soldiers for the defense of their country.

It appears from a paragraph in Governor Winthrop’s Journal, 12 that as early as December 1637, a number of respectable gentlemen, with others, had associated in a military company, and requested to be made a corporation. “But the council, considering from the example of the Praetorian band, among the Romans, and the Templars 13 in Europe, how dangerous it might be to erect a standing authority of military men, which might easily, in time, overthrow the civil power,” thought fit to decline granting their request. However, on the 24th of April following the Governor and Council established the Company by the name of “THE MILITARY COMPANY OF THE MASSACHUSETTS;” but they expressly provided that nothing, contained in their charter, should “extend to free the said company, or any of them, their persons or estates, from the civil government and jurisdiction” of the commonwealth.

This association, as we are informed in the preamble or their charter, originated from a concern in its members for “the public weal and safety; and to promote these, by the advancement of the military art and exercise of arms.” The situation of New England, at this period, was peculiarly calculated to inspire a disposition to promote military discipline. A long, distressing, and very bloody war, the first which had happened between the English and the Indians, in which the Pequod nation were utterly exterminated, had just closed. 14 Although the success of this war on the part of the English was so signal and complete, as to refrain the surrounding Indian tribes from waging open war for nearly forty years after; 15 yet, as this effect could not be foreseen, all felt the necessity of being armed, disciplined, and prepared for any emergency. Hence too the disposition in the government to patronize and distinguish it with peculiar privileges.

Its original charter, 16 grants liberty to choose its own officers, the two first in grade to be always such, as the Court or Council shall approve. Members of this company, (officers of other trained bands excepted,) were excused from ordinary trainings. The first Monday in every month was appointed for their meeting and exercise; and that they might not be interrupted, all other trainings, and particular town meetings, were prohibited on these days. They were also empowered to make, and by fines to enforce, such regulations for the management of their military affairs, as they might think expedient, which should be of force, when allowed by the Court. They had liberty to meet for military exercises in any town within the jurisdiction. And to assist them in defraying expenses, incident to their extraordinary exertions for promoting military discipline, the Court granted them first one thousand, and afterward in addition five hundred acres of land, for their use and that of their successors for ever. If we except the Roman, Praetorian band, no military association perhaps was ever distinguished by government, with similar privileges. The Council, by subjecting the association to the civil authority, while at the same time they extended to it liberal patronage, manifested great discernment and prudence, as they effectually secured all the advantages, while they avoided the dangers of the Praetorian band.

It appears, that the company at its commencement was composed in part at least, of some of the first men in the colony. Men of like character have ever since been ranked among its members. Before the close of a century from its establishment, the association, from the high respectability of its members, and from its extensive and acknowledged usefulness, received the name of “THE ANCIENT AND HONORABLE ARTILLERY COMPANY OF MASSACHUSETTS,” which name it still merits and retains.

The best institutions have their seasons of decline. Such a season, it appears this company experienced previously to the year 1700. A long time it had continued “a nursery for training up soldiers in military discipline, and who had been prepared for, and employed in, the service of their king and country.” 17 From various causes, not recorded, it had been for several years “under some decay.” Anxious to preserve the reputation, honor, and good influence of their institution, the company, in September 1700, met, and revised their former grants and orders, and considered what part of them might with propriety be annulled, and what additions made, to meet the increase and improved state of the country. The result was that the three, instead of the two first officers of the company, should be allowed by the Governor; that they should have liberty to meet for military exercises, not in “any town within the jurisdiction,” but, “in any neighbouring town at their discretion;” that instead of the first Monday in every month, training days should in future be the Election day, being the first Monday in June, annually, and the first Mondays in September, October, April, and May; that out of the several companies in Boston there may be enlisted 40 soldiers and no more; that upon the reasonable request of any member of the company they may have their dismission granted: The names of such are enrolled on an honorary list, kept for the purpose. 18

Though the great changes in the state of the country rendered it less necessary for the company to claim rigid respect to some of their peculiar privileges; yet as late as April 1st, 1748, one of the training days of the company, a town meeting called in Boston on this day, was declared illegal, null, and void, because contrary to their charter. 19 At a recent period also, I have been informed, a commanding officer of another military company, having inadvertently ordered out his soldiers on one of the training days of the honorable artillery company, very politely countermanded the order, as an infringement of their ancient rights.

This company, from the beginning, has shared the countenance and patronage of the public. No other company has succeeded in procuring like privileges. Its funds are exempted from taxes; its anniversaries have ever been celebrated by religious solemnities, as well as by military exhibitions, and honored with the presence of the civil fathers of the commonwealth, of numbers of the clergy, and of many other respectable members of the community.

Care is taken in the choice of members, to preserve the reputation of the company. None are admitted, but by a concurrence of three quarters of the votes; and sureties are required for their good behavior. Upward of fourteen hundred persons have been members of this association since its establishment.

Previous to the year 1767, owing in part to the extraordinary expenses, necessarily incurred by the officers, the association experienced another decline. Timely and effectual exertions however were made, to revive it again.

In 1772 the threatening aspect of public affairs awakened the attention of this company. Elevated by their profession and privileges, as centinels to watch the movements of those, who meditated evil against the commonwealth, it became them to take the lead in military preparations for the last resort. They were not ignorant of their duties, nor unfaithful in performing them. They resolved to adopt a uniform dress, to be very particular in the selection of their members, and strict and punctual in observing the rules of their institution. These and other vigorous measures were adopted with a view to inspire a military spirit into their own body, and to diffuse it among their fellow citizens. These exertions were continued with no inconsiderable effect, we may presume to say, upon the interesting transactions of that portentous period, till the opening of the revolutionary war in April 1775. In this war many of the members of this company engaged, and some, whose names adorn their records, acted very distinguished parts, both in the field and in the cabinet; whose names will with honor descend to posterity on the pages of history.

From April 1775 to August 1786, the company for obvious reasons intermitted their regular meetings. At the period, last mentioned, they reassembled, and organized themselves under their last elected officers. This was another period of danger, and these patriots and veterans were prompt in their preparations to meet it. A formidable insurrection, which for some time had been generating from a combination of causes, in the subsequent autumn burst forth in the western parts of this commonwealth, under the direction of Daniel Shays, and others, which threatened the most serious consequences, not to this state only, but to our whole country. At this anxious period, when all the blessings, purchased by the blood and treasure of our citizens, was put to the most imminent hazard, this patriot band, descrying the danger, and animated with noble ardor to repel it, at the call of the commander in chief declared, immediately and unanimously, “their readiness (these are their own words) to exert themselves in every thing in their power to support the government of the commonwealth, and to hold themselves in readiness, on the shortest notice, to turn out in defense of the same.” Accordingly they appeared foremost in discharging the duties of this momentous crisis. Considering their character as men, as patriots, and as soldiers, their example must have had a commanding influence upon others; and at so critical a moment, when many hesitated on which side to engage, when a short delay, a little less resolution and spirit manifested, would have turned the scale in favor of anarchy, it is probably doing but justice, to say that this ancient and honorable company, under Providence, contributed much, very much to the salvation of this state, of our country, and of all in this world, that our hearts hold dear.

Since this period under the smiles of heaven, our country has enjoyed peace and prosperity, and of course the history of this institution has been marked with no prominent event. Its time of action is, when the interests of our country are put to the hazard by invading foes. Its post of honor is the post of danger. It is sufficient, that in times of peace its members hold themselves prepared for war.

A remarkable feature of this honorable association must not escape our notice. On the day of election new officers are always chosen, and those of the preceding year return to the ranks, and continue to perform the duties of privates, till again promoted at some future election. This is done with appropriate ceremonies on the public common, in presence of the Governor and Council, surrounded with a crowd of spectators. “This is the very marrow and pith of republicanism.

A military association, founded in the purest age of New England, at once subject to, and nurtured by the government, highly republican in its principles, embracing, as it has done, in successive periods, so many characters of distinction and worth, reverencing the religious institutions of their country, must have diffused a salutary influence over the commonwealth. Placed, as a city on a hill, distinguished by their privileges, sensible that to whom much is given of them much is required, they must have felt a peculiar responsibility, and taken unusual pains to perfect themselves in the art military. They must have been, more especially in the infancy of the country, an example, which other military companies would aspire to imitate. The members, not belonging to a single town, but dispersed over the commonwealth, carried home with them a military spirit, and the knowledge of correct discipline, and spread them among their neighbors. When they emigrated into the surrounding provinces, thither also they conveyed their disciplinary and tactical improvements. This company, no doubt, has had large influence directly and remotely, in raising the military character of New England. Like leaven, it has operated in leavening the whole lump.

It is presumed, that nothing, which has now been said of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery, will be so construed, as to detract in any degree from the merit of our respectable militia, or from the high reputation of the many volunteer companies, formed in various parts of the commonwealth, several of which, in point of skill and exactness in military maneuvers and discipline, vie with the parent institution. As to the militia it is enough, that their Commander in Chief has said that, their body, “was never perhaps in a more respectable condition, than at present.” 20

My subject, I fear has led me to trespass already too long upon your patience. I must ask your indulgence, however, a few minutes longer, while I apply my discourse, first to the Ancient and Honorable Company, whose anniversary we this day celebrate; then to the audience at large.

Brethren, of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company.

Agreeably to a wish, expressed to me by your respected officers, I have attempted a summary history of your venerable institution. You cannot contemplate its origin, its uniform respectability, and extensive usefulness, without mingled emotions of devout gratitude, and virtuous emulation. Your Association was formed in perilous times by Christian patriots, trained up in scenes adapted to try their souls. It did not originate in ambition to create a military influence, to overawe the civil authority, and prostrate at its feet the liberties of the people; but in a just and pious concern for “the public weal and safety;” in a desire to co-operate in the military department with the legislative and executive authority, with the ministers of religion, and the cultivators and friends of science and literature, in laying deep, and broad, and secure, the foundations of the future peace, prosperity, and glory of New England. The piety and wisdom of our fathers led them to combine all their means and efforts, to produce the greatest possible good. We trust, brethren, that it will be your aim to keep in view the original design, of your association. It will be your study, how you shall most effectually preserve its high reputation, and render it most useful to the community. Should foreign foes again dare to invade our country’s rights, or anarchy to raise her hydra head in our own bosom, which may heaven forbid, you will be alert at the post of danger, and by your example inspire others to unite in repelling the aggressions and preventing the havoc of the presumptuous enemy. It will be your glory, as it was that of your renowned predecessors, to co-operate, in your department with all other useful institutions in promoting the safety, honor, and independence of our country. To this end you will place continually before you the excellent example of those of your predecessors, whose names adorn the list of your members; you will imbibe their spirit, emulate their moral and civic as well, as military virtues. Above all you will aspire to imitate their piety toward God, their zeal for his honor, their reverence for his Sabbath and ordinances: You will, in a word, be Christian patriots, and good soldiers of Jesus Christ. “Watch ye, stand fast in the faith, quit you like men, be strong.” So shall your ancient company still remain honorable, preserve its high rank, its respectable patronage, and extensive influence; and you yourselves, my brethren, having followed your predecessors, who through faith and patience now inherit the promises; having, like those Christian heroes, fought the good fight, finished your course, and kept the faith, you will receive from the righteous Judge the crown of righteousness the laurel of victory, that fadeth not away.

The view we have taken of the settlement of Newengland, and of the character and institutions of our venerable ancestors, furnishes to us all abundant matter for useful reflection. The hand of God was very visible in planting this country, in sustaining, protecting, and prospering its first Christian inhabitants. They were a chosen generation, and received wisdom from above to enact laws, and establish institutions, surpassing in excellence and utility those of perhaps any other nation under heaven. It is our honor and our privilege to have descended from such progenitors, to live under such laws, to enjoy the benefits of such institutions. Amid dangers, and trials, and hardships of which we can have but a faint idea, our fathers planted, God in his abundant goodness watered, and we are reaping, in manifold blessings, a large increase. Seeing these things are so, what manner of persons ought we to be in all holy conversation and godliness? How fervent should be our gratitude to God; how warm and enlightened our zeal for his honor; how cheerful and perfect our obedience to all his holy laws and institutions?

It is said of Rome, that “in her youth and manhood she was the seat of piety, of the purest patriotism, simplicity of manners, justice, honor, temperance, frugality, and splendid poverty.” Among all the heathen nations none perhaps ever enjoyed more light, advantages, and blessings, than the Romans, till the introduction of luxury; when money became the sole object of pursuit, and all veneration for religion, oaths, justice, and modesty, was by degrees annihilated. Their punishment was proportioned to the privileges and blessings, which they had enjoyed, and to the sins by which they had forfeited them. Tacitus thus describes their degenerate state. “Most hideous were the ravages of cruelty at Rome: for there it was treasonable to be noble; capital to be rich; criminal to have sustained honors; criminal to have declined them; and the reward of worth was quick and inevitable destruction. There the baneful villanies of informers were not more shocking, than their mighty and distinguishing rewards,” (for on them were conferred the most honorable and lucrative offices of the empire,) while “every station, exerting all their terrors, and pursuing their hate, they controlled and confounded all things; slaves were suborned to accuse their masters; freedmen their patrons; and such as had no enemies, were betrayed and undone by their friends.”

The Jews furnish an example still more in point. They were God’s peculiar people, on whom he bestowed his richest favors. He dealt so with no other nation. When they were but few in number, yea a very few and strangers; when they went from one nation to another, from one kingdom to another people, he suffered no man to do them wrong: Yea he reproved kings for their sakes. He increased his people greatly, and made them stronger, than their enemies. He sent Moses his servant, and Aaron, whom he had chosen, to lead them forth by a right way; and gave them the land of the heathen, that they might observe his statutes and keep his laws. Jacob was the lot of his inheritance; he instructed him, he kept him, as the apple of his eye. He made him to eat of the increase of the fields, and to suck honey and oil out of the rock. Butter of kine, did he give them, and milk of sheep, with fat of lambs, and kidneys of wheat, and they drank of the pure blood of the grape. This happy state of things continued so long as this people remained faithful in the service of the God of their fathers. “But Jeshurun waxed fat and kicked; and forsook God, who made him, and lightly esteemed the rock of his salvation. And, when the Lord saw it, he abhorred them, because of the provoking of his sons and his daughters.” The scene was reversed. Their blessing was turned into a curse; and their condition became as deplorable, as it was before prosperous. All this evil came upon them, because they had “forsaken the Lord God of their fathers, and served other gods.”

If then, like the ancient Romans, we lose our veneration for religion and its sacred institutions, our regard to justice and modesty, with our love of country; if we suffer luxury to destroy our simplicity of manners, and to create artificial wants, and money to become the chief object of our pursuit; if by any means we become so politically depraved, as that vice shall triumph and “impious men bear sway,” and the honorable man shall be found only in the private walks of life. Or, if, like Jeshurun, we wax fat and wanton in our prosperity, and depart from the old paths and the good way, and forsake the God of our fathers, the Rock of our salvation, then we may be assured, our destruction draweth nigh. And, when God shall enter into judgment with New England, it will be a day of his fiercest wrath. The plagues and miseries, inflicted by Jehovah on ancient Rome, on modern France, or even those poured out on his chosen people, are more tolerable, than those in store for us, if under our superior privileges, and more solemn warnings, we follow the example of these apostate nations. And are there not already upon us many symptoms of decline? Let us compare the modern with the primitive state of this part our country, and mark the difference. Oh that we were wise, that we understood this, that we would consider our latter end, and know the things, that belong to our peace, before they be hidden from our eyes!

Suffer me, in this connection, to address you in the solemn words of the excellent Gov. Stoughton: “Consider, and remember always, that the books, that shall be opened at the last day, will contain genealogies in them. There shall then be brought forth a register of the genealogies of New England’s sons and daughters. How shall we, many of us, hold up our faces then, when there shall be a solemn rehearsal of our descent, as well, as of our degeneracies! To have it published, whose child thou art, will be cutting to thy soul as well, as to have the crimes reckoned up, of which thou art guilty.” 21

But, though we have much to fear from our degeneracies, we have, through the mercy of our God, many things to encourage our hopes. Numerous and animating are the tokens of the favor of heaven, still visible among us, when we look into the state of our churches, of our colleges and schools, of our political, and military affairs. The institutions of our fathers still yield to us their increase, though the harvest is diminished and marred by our degeneracies. Shall we not then take courage, awake, unite, and strengthen the things which remain?

To this end let us “consider the days of old, the years of ancient times,” and reflect often on our descent, more highly to be valued, than that of kings and nobles. Let us venerate and by all means preserve uncorrupted, those institutions, which our fathers planted in their wisdom and piety, watered and cherished with their tears and their prayers, and defended with their blood; which have borne for their posterity so fair and plentiful a harvest of blessings. We cannot leave to our posterity a richer inheritance, than these institutions, in their primitive purity.

Let us guard against the insidious encroachments of innovation, that evil and beguiling spirit which is now stalking to and fro through the earth, seeking whom he may destroy. His business is to take off all salutary restraints upon the passions of men, to annihilate the force of law, to unkennel vice, to uncivilized man and reduce him to a state of nature. His path may be descried by the tears and groans of his seduced followers. It leads through the noisy, and bloody abodes of anarchy and wild misrule to the dreary, cheerless regions of despotism.

As we value our liberties and happiness, let us reject the visionary schemes of modern reformers; be contented with experimental knowledge; adhere unwaveringly to “the old paths and the good way,” in which our fathers walked, and found rest to their souls; cherish those found political and religious principles, and “steady habits,” which in this stormy period, will guide us safely, between Scylla and Charybdis, anarchy and despotism. Let those men, and those only, share the honors and offices of government, who are just, and will rule in the fear of God. If we see men anxious and intriguing for posts of trust and profit, uttering groundless clamors against those in office, claiming to be the exclusive friends of the people; calumniating the religion and the ministers of the gospel, and habitually neglecting its holy ordinances; indulging the lusts of the flesh, despising dominion, and speaking evil of dignities; we may be assured, such men are false hearted patriots; they are not to be trusted. “Clouds they are without water, carried about of winds; trees, whose fruit withereth; without fruit, twice dead, plucked up by the roots. Raging waves of the sea; foaming out their own shame; wandering stars, to whom is reserved the blackness of darkness for ever.”

While we diligently promote sound principles in religion, in politics, and science; while we study those things which make for peace; such are the hostile dispositions and attitudes of the nations of the earth; such our commercial connections with them, that it is necessary we be prepared for war. The example of Jehoshaphat, king of Judah, merits, in this connection, our notice and imitation. His kingdom was surrounded with enemies. He therefore wisely “strengthened himself against them; placed forces in all the fenced cities of Judah, and in the cities of Ephraim.” With these preparations for war he connected instruction in righteousness. “In the third year of his reign he sent of his princes to teach in the cities of Judah, and with them he sent Levites and priests. And they taught in Judah, and had the book of the law of the Lord with them, and went out through all the cities of Judah, and taught the people.” Mark the consequence of these combined efforts for the safety of the nation: “And the fear of the Lord fell upon all the kingdoms of the lands, that were round about Judah, so that they made no war against Jehoshaphat.”

Sound policy surely dictates to us the same means of national defense. We are taught by high authority, which will not be controverted, that “it will always be necessary to cultivate the military art, not to enable us to commit outrages with impunity, but to defend ourselves against the attempts of unprincipled and ambitious men, who consider all means, as lawful, that promote their ends; who make their glory consist in spreading misery through the world.” 22

A general knowledge of the art of war among a people, a manly attitude, preparations to meet meddlesome invaders, are necessary preservatives of honorable peace. Depraved and unprincipled men will be restrained only by fear. The wicked prey upon the defenseless. Pusillanimity ever invites insult and outrage. But, though ships and fortresses, the sword, the spear, and weapons of war, are good and necessary means of defense; yet the protection of God is far better; and without this they can avail us nothing. “Righteousness exalteth a nation to an honorable alliance with heaven, and sheltereth it behind the shield of omnipotence. Whatever, therefore, promotes righteousness, must be regarded by every man, who believes a Providence as a part of the national defense.” 23

Even the first Consul of the French nation, of whose military and political talents we have a higher opinion, than of the piety of his heart or the morality of his life, convinced, probably by the dreadful effects of abolishing Christianity in the nation which he now rules with a despotic arm, of the necessity of religion, is constrained to give it his sanction. “The principles of an enlightened religion, (he says) produce union in societies, and the happiest effect on public morals. From their consequence childhood is more docile to the instructions of parents, and youths more submissive to the authority of magistrates. 24

Finally, considering our honorable descent, our distinguished privileges, our consequent high obligations, what we owe to our God, and to our country, to ourselves and our posterity; let us all, magistrates and ministers, men of science and men of war, all of every occupation, and rank, and sex in the community, each in his lot, combine our efforts, to reform or exterminate every thing which mars or endangers our general happiness; and to cherish and invigorate all those things, which tend to promote and secure its continuance.

And now, in language, uttered by king David to an assembled princes, captains, and officers of his kingdom, with the mighty men and all the valiant men, permit me, as an ambassador of Christ, in the fight of this congregation, and in the audience of God, to charge you; “Seek for and keep, all the commandments of the Lord your God; that ye may possess this good land, and leave it for an inheritance to your children after you for ever.” 25

AMEN.If of an

enemy, and he be supposed to advocate religion because he may think it necessary to support a military despotism, while he acknowledges its high importance, and great effect, he utterly mistakes its true design and tendency. For “an enlightened religion,” if we understand by it

true religion, is hostile to every species of despotism, and friendly only to just and equal government. If of a

friend, and he be supposed to speak the language of conviction and sincerity, his talents, discernment and situation, render him a very competent witness; and his authority should have weight with those infidel, visionary theorists, who wish to see tried the experiment of a government administered without the aid of any religion.

NOTE [A].Having mentioned the “Platform of church discipline,” upon which the congregational churches in New England were established, and, which, to the great detriment of the purity, order and harmony of our churches has been for many years passing gradually into neglect and disuse, it may be useful to direct the attention of those who have the interests of evangelical truth at heart, to this subject. In connection with the foregoing quotation from Messrs. Higginson and Hubbard, the pious and learned Mr. Prince of Boston, makes the following observations, which are submitted to the serious attention of the civil fathers, and to the congregational ministers and churches of New England.

“The inspired scripture is our only authoritative rule of faith and worship; and our Platform is no other than the declared judgment of the sense of scripture in matters of church order, discipline and worship which our ancient ministers and others, 26 with abundant prayers and humble, free and diligent inquiries and conferences, almost unanimously came into. But then as no other people in these later ages have been favored with such advantages as the founders of these churches, to search into, discover and put in practice the Christian way of church order, discipline and worship described in the word of God; they being entirely men of piety, knowledge, judgment, the most about the middle age of life, who had made the bible their familiar study, many of them persons of superior learning, and all free from any influence of human powers and constitutions in religious matters; they wholly relinquished all devised schemes of men, and set themselves to consult the sacred scriptures only, that they might happily see what these directed, and submit thereto; and having renounced all prospects of worldly riches, powers and dignities, for this very end. They were on these accounts most likely to find out the truth in those affairs. And though our faith is not to be subjected to their judgment, but we should also humbly, sincerely and carefully search the scriptures, and try these things by them, and see whether they are conformable to those oracles of God or no, as the noble Bereans did when even the apostles taught them; yet the result of their united, pious, anxious and laborious inquiries, under such advantages, demands a very extraordinary veneration from all impartial men, and especially from us their dear posterity.

“And can we do any thing better, both for the advantage of our ministry, the satisfaction of our people, and the quiet of our churches, than to go on upon the scriptural foundations these excellent men have already laid? Not to set aside or build anew, but to go on further as the light of scripture leads us, for our common peace and edification. And I know of nothing of greater moment, than to advise to methods about calling councils in a fairer, more peaceable, equal and harmonious manner, than we are now unhappily liable to; that so this sacred ordinance may not be so subject to be frustrated by the dark intrigues of crafty men, nor anti-councils raised to support contending parties to the great dishonor of Christ, the grief of all good men, and the inflammation and continuance of hatred and divisions.

“And how happy for these churches, and for all this country both to this and future generations, as I would with submission hope, if with the countenance and invitation of our civil fathers, we might have a synod in due time convened; not to make the least injunctions upon any, which is contrary to our known principles, but only to advise and propose those methods which may conduce to the promoting piety, peace and good order in our own churches; but left to every one to receive or not, as they think best. Two such happy synods we had in the reign of king Charles I. and two more in the reign of king Charles II. Without offence; invited by the civil rulers who also sat among them as chosen representatives of our churches, and as grave advisors with the rest, but all without the least coercive power. Our New England synods are not like those of other countries, who make decrees or canons, but for counsel only, for the peace and order of the churches who send their pastors and other delegates to consult together and give their rulers by deriving any power to such a synod, or in inviting the churches to them, the churches being always left at liberty whether to fend or no, to comply or no; there can be no invasion on any power in such a free invitation; it being impossible as I humbly apprehended, there should be any power invaded, where there is none assumed.”

NOTE [B].The

Praetorian band was a body of guards amounting to about 15,000 men, distinguished by double pay, and by privileges superior to the soldiers of the legions. This band was formed by Augustus, who stationed three cohorts, consisting of about 1500 men, in the capital during his reign. Tiberius afterwards assembled the whole corps at Rome, and there established them in a permanent camp, advantageously situated, and well fortified. In the year of our Lord 192,

Pertinax was declared Emperor, and to him the Praetorian band took the oath of allegiance. Eighty seven days after, several hundreds of their number, at noon day, marched toward the imperial palace, where their companions upon guard, immediately threw open the gates, and joined them in assassinating their virtuous and excellent Prince, whose head, after dispatching him with many wounds, they cut off, fixed upon a lance, and carried in triumph to their camp. In those moments of horror,

Sulpicianus, father in law of the murdered

Pertinax, dead to all honor and public virtue, began to treat with these murderers for the throne. Thinking that a higher price might be obtained by exposing it to a public sale, than by private contract, they ran to the ramparts, and with a loud voice, proclaimed that the

Roman world was to be sold at public auction, to the highest bidder. Julianus outbid Sulpicianus. The former promised each soldier 6250 drachms, equal to about 867 dollars, the latter 5000 drachms, equal to about 710 dollars. Accordingly, to Julianus they immediately threw open the gates of the camp, and declared him Emperor, took the oath of allegiance to him, placed him in the centre of their ranks, surrounded him on every side with their shields, and proceeded with him through the deserted streets of Rome, to the Senate, who dared not resist, but pretended great satisfaction at the happy revolution, and acknowledged him Emperor.

27 With this example before them, the fathers of New England would not have acted with their usual wisdom, had they laid the foundation of so fatal a military despotism in their government.

The Templars were a religious order, instituted at Jerusalem, in the beginning of the 12th century, for the defense of the holy sepulcher and the protection of Christian pilgrims. In every nation they had a particular governor, called Master of the Temple, or of the Militia of the Temple. The grand master had his residence at Paris. The order flourished for some time, acquired immense riches, and great military renown. As their prosperity increased, however, their vices multiplied, and their arrogance, luxury and cruelty rose at last to such a monstrous height, that their privileges were revoked, and their order suppressed, with the most terrible circumstances of infamy and severity. Encyclopedia Art. Templars.

Endnotes

1. Bennet’s Historical Account of the several attempts for a further reformation. Also, Foxcroft’s Sermon on the Beginning of Newengland; preached August, 1730.

2. Stoughton’s Election Sermon, April 29, 1668.

3. Foxcroft, page 22.

4. Foxcroft, page 19, Note.

5. Foxcroft, page 25.

6. Quoted in Prince’s Election Sermon, of 1730, p. 41, 42.

7. See Note [A].

8. Election Sermon, page 39.

9. In his Election Sermon.

10. Prince, page 39.

11. 1636. It received the name of Harvard College in 1638.

12. Page 147.

13. See Note [B].

14. See Hutchinson, vol. I. p. 80. Winthrop’s Journal, p. 142 to 147.

15. Hutchinson, vol. I. page 80.

16. See the Records of the Company.

17. Records, page 3.

18. Records, page 3.

19. See Records of this date.

20. See his Excellency’s Speech to the Legislature, May 1803.

21. Election Sermon.

22. Governor Strong’s Speech, May 1803.

23. Ferrier’s Sermon.

24. See a state paper entitled “A view of the state of the French republic, sent by Bonaparte to the legislative body on the 22d Feb. 1803, translated in the Centinel of May 25.

Whatever motives may have prompted Bonaparte to pronounce this eulogy upon religion, it must be received as his testimony in its favor. Of the credibility of this witness each reader will form his own opinion. If it be received as the testimony of an enemy or a friend, in either case it has weight.

25. I Chron. 28, 1 8.

26. “I say others, because it has been a fundamental principle with us, that as churches are composed both of ministers and brethren, and ecclesiastical councils or synods are proper representatives of churches; that therefore there should set in all such assemblies, not only ministers, but also others chosen by the churches to represent them; that they may not be merely clerical, or synods of the clergy, but ecclesiastical, or synods of the churches. And such have been all our Newengland synods and councils from the first; agreeable to that famous precedent in Acts XV.”

27. Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.