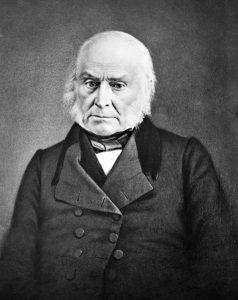

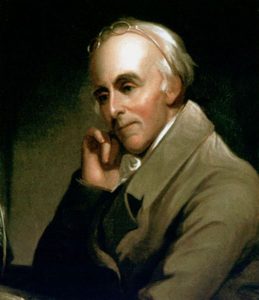

John Adams (1735-1826) Adams was an attorney, diplomat, and statesman; he graduated from Harvard (1755); leader in the opposition to the Stamp Act (1765); delegate to the Continental Congress (1774-77) where he signed the Declaration of Independence (1776); appointed Chief Justice of Superior Court of Massachusetts (1775); delegate to the Massachusetts constitutional convention (1779-80) and wrote most of the first draft of the Massachusetts Constitution; foreign ambassador to Holland (1782); signed the peace treaty which ended the American Revolution (1783); foreign ambassador to Great Britain (1785-88); served two terms as Vice-President under President George Washington (1789-97); second President of the United States (1797-1801); he and his one time political nemesis- turned-close-friend Thomas Jefferson both died on July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence; Adams was titled by fellow signer of the Declaration Richard Stockton as the “Atlas of American Independence.”

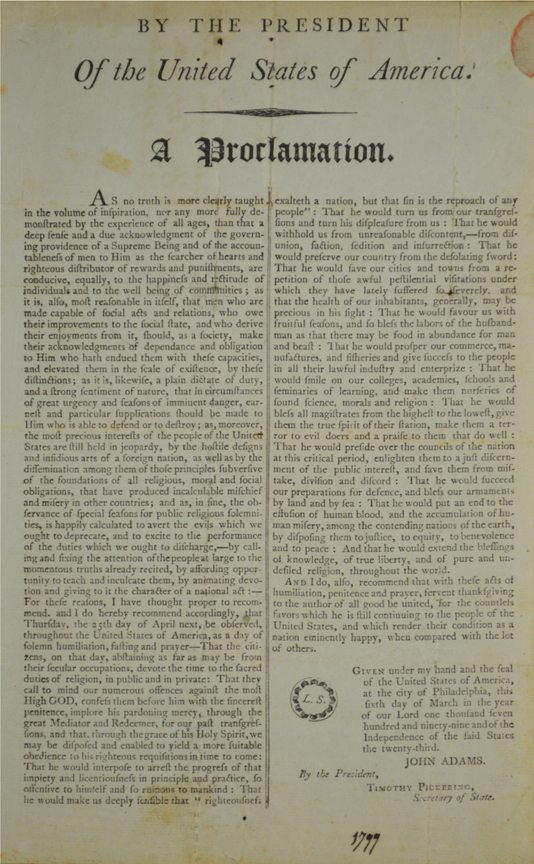

This is the text of a national day of humiliation, fasting, and prayer proclamation issued by President John Adams. This proclamation was issued on March 6, 1799 declaring April 25, 1799 the day of fasting for the nation. See a sermon preached by Rev. Manneseh Cutler on the 1799 fast day here.

By the President of the United States of America.

A Proclamation.

As no truth is more clearly taught in the Volume of Inspiration, nor any more fully demonstrated by the experience of all ages, than that a deep sense and a due acknowledgment of the governing providence of a Supreme Being and of the accountableness of men to Him as the searcher of hearts and righteous distributor of rewards and punishments are conducive equally to the happiness and rectitude of individuals and to the well-being of communities; as it is also most reasonable in itself that men who are made capable of social acts and relations, who owe their improvements to the social state, and who derive their enjoyments from it, should, as a society, make their acknowledgments of dependence and obligation to Him who hath endowed them with these capacities and elevated them in the scale of existence by these distinctions; as it is likewise a plain dictate of duty and a strong sentiment of nature that in circumstances of great urgency and seasons of imminent danger earnest and particular supplications should be made to Him who is able to defend or to destroy; as, moreover, the most precious interests of the people of the United States are still held in jeopardy by the hostile designs and insidious acts of a foreign nation, as well as by the dissemination among them of those principles, subversive of the foundations of all religious, moral, and social obligations, that have produced incalculable mischief and misery in other countries; and as, in fine, the observance of special seasons for public religious solemnities is happily calculated to avert the evils which we ought to deprecate and to excite to the performance of the duties which we ought to discharge by calling and fixing the attention of the people at large to the momentous truths already recited, by affording opportunity to teach and inculcate them by animating devotion and giving to it the character of a national act:

For these reasons I have thought proper to recommend, and I do hereby recommend accordingly, that Thursday, the Twenty-fifth day of April next, be observed throughout the United States of America as a day of solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer; that the citizens on that day abstain as far as may be from their secular occupations, devote the time to the sacred duties of religion in public and in private; that they call to mind our numerous offenses against the Most High God, confess them before Him with the sincerest penitence, implore His pardoning mercy, through the Great Mediator and Redeemer, for our past transgressions, and that through the grace of His Holy Spirit we may be disposed and enabled to yield a more suitable obedience to His righteous requisitions in time to come; that He would interpose to arrest the progress of that impiety and licentiousness in principle and practice so offensive to Himself and so ruinous to mankind; that He would make us deeply sensible that “righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people;” that He would turn us from our transgressions and turn His displeasure from us; that He would withhold us from unreasonable discontent, from disunion, faction, sedition, and insurrection; that He would preserve our country from the desolating sword; that He would save our cities and towns from a repetition of those awful pestilential visitations under which they have lately suffered so severely, and that the health of our inhabitants generally may be precious in His sight; that He would favor us with fruitful seasons and so bless the labors of the husbandman as that there may be food in abundance for man and beast; that He would prosper our commerce, manufactures, and fisheries, and give success to the people in all their lawful industry and enterprise; that He would smile on our colleges, academies, schools, and seminaries of learning, and make them nurseries of sound science, morals, and religion; that He would bless all magistrates, from the highest to the lowest, give them the true spirit of their station, make them a terror to evil doers and a praise to them that do well; that He would preside over the councils of the nation at this critical period, enlighten them to a just discernment of the public interest, and save them from mistake, division, and discord; that He would make succeed our preparations for defense and bless our armaments by land and by sea; that He would put an end to the effusion of human blood and the accumulation of human misery among the contending nations of the earth by disposing them to justice, to equity, to benevolence, and to peace; and that he would extend the blessings of knowledge, of true liberty. and of pure and undefiled religion throughout the world.

And I do, also, recommend that with these acts of humiliation, penitence, and prayer, fervent thanksgiving to the Author of all good be united for the countless favors which He is still continuing to the people of the United States, and which render their condition as a nation eminently happy when compared with the lot of others.

Given, under my hand and the seal of the United States of America, at the city of Philadelphia, this sixth day of March, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and ninety nine, and of the Independence of the said States the twenty-third.

By the President, John Adams.

Timothy Pickering, Secretary of State.

* Originally Posted: September 9, 2017

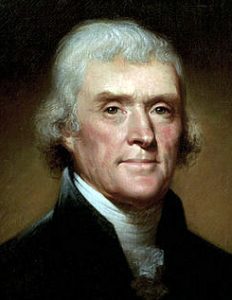

When writing to Thomas Jefferson on June 28, 1813, John Adams discusses the fact that America achieved independence through the general principles of Christianity. The letter itself, however, was the culmination of events which began nearly fifteen years earlier.

When writing to Thomas Jefferson on June 28, 1813, John Adams discusses the fact that America achieved independence through the general principles of Christianity. The letter itself, however, was the culmination of events which began nearly fifteen years earlier. After waiting for twelve days without a response, Adams again took up his pen on June 10, 1813, and went through the 1801 Jefferson letter responding to the various claims made against him. Adams focused on the part where Jefferson had quoted him, writing: “The President himself declaring that we were never to expect to go beyond them in real science.”

After waiting for twelve days without a response, Adams again took up his pen on June 10, 1813, and went through the 1801 Jefferson letter responding to the various claims made against him. Adams focused on the part where Jefferson had quoted him, writing: “The President himself declaring that we were never to expect to go beyond them in real science.”

On

On  Biblical faith permeated Morse’s life. For example, in an

Biblical faith permeated Morse’s life. For example, in an

June 14th is the birthday of the Army, created by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775.

June 14th is the birthday of the Army, created by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775. We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood (like France)–if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage–if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth–if the Star-Spangled Banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization–we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.

We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood (like France)–if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage–if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth–if the Star-Spangled Banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization–we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us. And in WWII, General George Marshall spoke about the mission of the United States:

And in WWII, General George Marshall spoke about the mission of the United States:

I advise you, my son, in whatever you read, and most of all in reading the Bible, to remember that it is for the purpose of making you wiser and more virtuous. I have myself, for many years, made it a practice to read through the Bible once every year. I have always endeavored to read it with the same spirit and temper of mind, which I now recommend to you: that is, with the intention and desire that it may contribute to my advancement in wisdom and virtue.

I advise you, my son, in whatever you read, and most of all in reading the Bible, to remember that it is for the purpose of making you wiser and more virtuous. I have myself, for many years, made it a practice to read through the Bible once every year. I have always endeavored to read it with the same spirit and temper of mind, which I now recommend to you: that is, with the intention and desire that it may contribute to my advancement in wisdom and virtue. I was much mortified to find the whole force of this man’s vain genius pointed at the youth of America….This awful consequence created some alarm in my mind lest at any future day you, my beloved child, might take up this plausible address of infidelity….I have endeavored to…show his extreme ignorance of the Divine Scriptures…not knowing that “they are the power of God unto salvation, to everyone that believeth” [Romans 1:16].

I was much mortified to find the whole force of this man’s vain genius pointed at the youth of America….This awful consequence created some alarm in my mind lest at any future day you, my beloved child, might take up this plausible address of infidelity….I have endeavored to…show his extreme ignorance of the Divine Scriptures…not knowing that “they are the power of God unto salvation, to everyone that believeth” [Romans 1:16].

President John Adams oversaw the construction of the Navy,

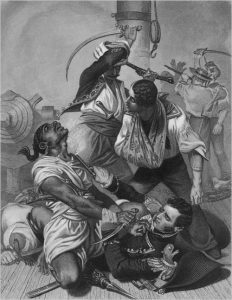

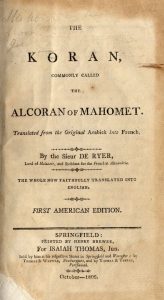

President John Adams oversaw the construction of the Navy, In short, if you read the Koran, you will understand their unprovoked attacks against us. But the fighting still wasn’t over. While America was engaged in the War of 1812 against Great Britain, Algiers (one of the Muslim Powers that had negotiated a peace treaty with the US in 1795

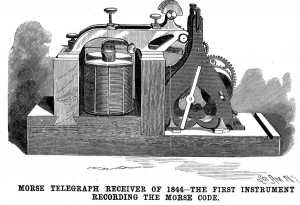

In short, if you read the Koran, you will understand their unprovoked attacks against us. But the fighting still wasn’t over. While America was engaged in the War of 1812 against Great Britain, Algiers (one of the Muslim Powers that had negotiated a peace treaty with the US in 1795 Morse’s pious character clearly exhibits itself in the historic message relayed during the public demonstration of the telegraph on May 24, 1844. Morse had promised Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the Commissioner of Patents that she would get to decide what would be said. After talking with her mother, Annie decided to send a portion from Numbers 23:23: “What hath God wrought!”

Morse’s pious character clearly exhibits itself in the historic message relayed during the public demonstration of the telegraph on May 24, 1844. Morse had promised Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the Commissioner of Patents that she would get to decide what would be said. After talking with her mother, Annie decided to send a portion from Numbers 23:23: “What hath God wrought!”

On March 3rd, 1931, an

On March 3rd, 1931, an  At that time, attorney Francis Scott Key

At that time, attorney Francis Scott Key

Easter is celebrated across the world as one of the most significant Christian holy days — as a time when we pause to remember the great sacrifice of Jesus on the cross as well as the ultimate triumph of His resurrection. America’s Founding Fathers often commented on Easter.

Easter is celebrated across the world as one of the most significant Christian holy days — as a time when we pause to remember the great sacrifice of Jesus on the cross as well as the ultimate triumph of His resurrection. America’s Founding Fathers often commented on Easter. The approaching festival of Easter, and the merits and mercies of our Redeemer copiosa assudeum redemptio [with the Lord there is plentiful redemption] have lead me into this chain of meditation and reasoning, and have inspired me with the hope of finding mercy before my Judge, and of being happy in the life to come — a happiness I wish you to participate with me by infusing into your heart a similar hope.

The approaching festival of Easter, and the merits and mercies of our Redeemer copiosa assudeum redemptio [with the Lord there is plentiful redemption] have lead me into this chain of meditation and reasoning, and have inspired me with the hope of finding mercy before my Judge, and of being happy in the life to come — a happiness I wish you to participate with me by infusing into your heart a similar hope. He forgave the crime of murder on His cross; and after His resurrection, He commanded His disciples to preach the gospel of forgiveness, first at Jerusalem, where He well knew His murderers still resided. These striking facts are recorded for our imitation and seem intended to show that the Son of God died, not only to reconcile God to man but to reconcile men to each other.

He forgave the crime of murder on His cross; and after His resurrection, He commanded His disciples to preach the gospel of forgiveness, first at Jerusalem, where He well knew His murderers still resided. These striking facts are recorded for our imitation and seem intended to show that the Son of God died, not only to reconcile God to man but to reconcile men to each other.