Joseph Lyman (1749-1826) graduated from Yale in 1767 and was pastor of a church in Hatfield, MA (1772-1826). This election sermon was preached by Rev. Lyman in Boston, MA on May 30, 1787.

SERMON

PREACHED BEFORE

His Excellency JAMES BOWDOIN, ESQ.

GOVERNOR

His Honor THOMAS CUSHING, Esq.

Lieutenant – Governor;

the Honorable the Council, And the Honorable the Senate, And the House of Representatives,

Of the Commonwealth of

MASSACHUSETTS

May 30, 1787

Being the Day of GENERAL ELECTION

By Rev. JOSEPH LYMAN

Pastor of the Church in Hatfield

Boston:

Printed by ADAMS and NOURSE

Printers to the Honorable the General Court

ROMANS, Chap. 13: 4, first clause

For he is the Minister of God to thee for good.

And this is the minister’s happiness, that he is ready furnished with instructions suited to every auditory before whom we may speak. All men need instruction, to be prompted to the discharge of their supreme obligation to God, and their relative obligations to each other: And this their common privilege that the blessed Jesus by his written word and preached gospel, provides for all a portion in due season.

The words selected for the basis of a discourse upon the present occasion, contain instruction for rulers; to point them to the origin of their power and the use they should make of it: They comprise a lesson equally useful to subjects; how to conduct themselves in relation to their rulers, and what views to entertain of their authority.

Should the Preacher conform himself to the text, and place to view the solemn importance of it, the present occasion might be richly profitable to this great assembly. May that Divine Teacher, who spake as never man spake, by the aids of his a Spirit, assist the Preacher to find out acceptable words and the words of truth and soberness; to recommend his doctrines in their purity and power to his servants, now convened to learn the law in his sanctuary.

-

- I. That civil authority is of divine institution.

-

- II. That civil authority is instituted for the good of the people in general, and for the benefit of the church of Christ in particular.

-

- III. What measures must the civil authority pursue to answer the end of their institutions?

- IV. What are the obligations of subjects to the civil authority?

Order is Heaven’s first law. Without it the gracious designs of the Creator cannot be accomplished. He has made his creatures of various powers and degrees; rising by an easy and happy graduation, from the lowest species of animals, to the most exalted rank of heavenly intelligencies. Creatures of the same species are constituted with certain differences, by which they greatly excel each other. Men, who are said to be born in a state of equality, are yet endowed with unequal measures of strength and wisdom. And hence there is a greater variety amongst men, than amongst several species of animals. Some are qualified to teach and guide; others to be taught and led by their superiors. To affirm that in the qualifications to rule and guide, all men are equal, is to blend characters totally diverse, to confound wisdom and folly, and affability and condescension with ill-nature and pride. There have been distinctions in the world, and various degrees amongst men; while endowed with such various qualities and affections, the distinction will remain. To gainsay this distinction, is to counteract one of the principal laws of humanity. Some must be in authority; others in subordination. And happy id that people who are allowed in Providence, to look out from among their brethren persons of the best disposition, and most aptly qualified to rule over them.

That particular persons should be distinguished and exalted in society, may be argued from the methods of Providence, ever since man hath been upon earth. No people were ever able to subsist for a length of time, without forming into some kind of civil government, and setting aside those boasted equalities, with which men are born into the world. They must be subject to some common rule and authority, in order to possess any measure of happiness and security. Where there are no rulers to govern the community, all things are immediately involved in confusion and misery. The countenance of our original equality is a state of nature, and all ages have found a state of nature to be a state of war. Therefore it has pleased the common Parent of man, to lead them to a state of civil subordination , by which a part of the community are intrusted to ordain and carry into effect, laws and regulations for that whole.

That the establishment of civil government is by the counsel with wisdom of God, we are taught both from the history of his Providence, and the testimony of his inspired truth. Israel, the people of his love, were formed into a civil community, and made subordinate to established laws, to be administered by rulers appointed by rulers appointed for that purpose. And it was time of sore rebuke, when there was no magistrate in the land of sufficient authority, to put them in fear. The exaltation and degradation of rulers is the work of god, and not the production of a blind and fortuitous chance, according to the opinion of idle and infidel wits. For faith the word of enlightening truth: Promotion cometh neither from the east, nor from the west, nor from the south. But God is the Judge; he putteth down one and setteth up another. The prerogative of ordaining magistracy and civil authority belongs to our Lord Jesus Christ; this claim he assumes to himself under the name of Wisdom. “By me Kings reign and Princes decree justice. By me Princes rule, and nobles, even all the judges of the earth.” These words imply the power of God, in supporting civil authority, and also his approbation of civil magistracy, as one of the blessings of the Redeemer’s purchase. In what estimation the blessing of civil government is holden by God, may be learned from the apostolical direction to Titus, how to teach the flock of Christ.

“Put them in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, and to obey magistrates.” So far is Christ interested in the support of civil authority, that he will acknowledge those only to his be his followers, who willingly obey rulers, and submit to their administrations.

But we need not go far for arguments: Our text is encompassed with proofs of the divine institution of civil authority. The argument in the first verse, for subjection to the higher powers, is, for there is no power but of god: the powers that be are ordained by God. The reason alleged for not opposing the power, is in the second verse. Whosoever resisteth the power resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation. Thrice in this argument the Apostle stiles the magistrate, God’s minister; that is, a public servant appointed by God. He is stiled also into God’s revenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil. And Christians must needs be subject, not only from fear and constraint, but cheerfully in discharge of a good conscience. Therefore our argument for the Divine institution of civil authority, rests upon the uniformity of Providence, in bringing mankind under government; upon he clear testimony of scripture; and upon our Lord’s repeated instructions to his disciples to yield a willing homage to rulers, even when they are neither of their faith, nor even of exemplary morals.

Not that God hath ordained any particular form of Government. This is left to the judgment of men, and the circumstance of particular countries and communities. But some government is necessary. God wills mankind to be in subordination, and that they stand to each other in the relation of rulers and subjects. He does not set up the claim of Kings, to an indefeatible and hereditary right: Such a claim is without support n scripture, and is repugnant to common sense. The leading idea of scripture is, that communities constitute certain of their brethren to rule over them: and thus constituted, they the ordinance of the Supreme Ruler.

Our argument is not, hat every power which assumes to be authority is really so; or that God would have it acknowledged as his institution. Usurpers and incurable tyrants are not the ordinance of God. Invaders are to be rejected as hostile to civil authority and subversive of government. The Apostle would show, that rulers allowed by long use, submitted to by promises of allegiance, or introduced according to the stated maxims of the community over whom they preside, are invested with power by God himself, and are to be obeyed by Christians as his ordinance; and this, however their characters may be faulty, and their administrations in many respects injudicious and reprehensible.

I proceed to prove,

That God has instituted civil authority for the common good, is a full demonstration, that he utterly abhors that tyranny and oppression, which is so frequently practiced by the intolerant Rulers of the earth: His benevolence is incensed at the abuse of his gifts, and the perversion of those prayers and talents which he has bestowed upon magistrates for the happiness of his creatures. Rulers, who misapply their authority for their personal advantage, and use of force of the State, to feed their ambition and revenge, or to gratify the guilty passions of minions and favorites, at the expense of public misery, are singular objects of divine resentments, and a strange punishment is prepared for them by the righteous Avenger. No man has authority from God for partial advantage, but for the common good. And while God suffers such rulers to hold dominion among men, he utterly abhors the injustice and wickedness of their administrations; he will bring to swift destruction these haughty oppressors of the nations, and proportion his plagues to their violence, and to their fellow men. He will eventually shew his power, and makes his wrath known in their wonderful perdition.

But let none imagine, that God has no gracious purposes to answer by an iniquitous administration of civil government. Insatiable oppressors, bloody conquerors and imperial butchers, are of use in the scheme of Providence, to correct and amend the revolting tribes of men. While they make the earth to tremble, and turn fruitful fields into a desolate wilderness, they are the messengers of divine displeasure, the rod of God’s anger, and the staff of his indignation, against an hypocritical and rebellious people. If a wise and merciful administration will not correct the dissoluteness of an obdurate people, God scourges them with the stings of scorpions, with the relentless cruelty and ambition of unprincipled tyrants. Such dispensations are necessary, both to reclaim the disobedient, and as an example of retributive justice upon the incorrigible, that others may shun the rocks on which they split.

God’s judgments are full of mercy. That greatest temporal calamity which men experience, an unrighteous administration of civil power, has yet a gracious mixture of compassion, and tends to make perfect the scheme of Providence.

But a good and equal administration of government is a blessing to the community in a different sense. The enjoyments and tranquility of subjects are ae secured by the protection of rulers. To advance general happiness, to secure property, to increase true, rational liberty, and to preserve the lives of men, are the original purposes for which civil laws and magistrates are ordained by heaven. The Supreme Ruler has given to magistrates no warrant to pursue unequal or partial measures; to consult personal or family interests; nor to foster the wishes and pursuits of the cringing favorites.—The sword of the state is not committed to them for the exclusive advantage of particular societies or classes of men. To promote the general good, to cherish virtue, and to diffuse joyous prosperity through the whole community, are the ends for which God has exalted them to power. And they may pursue the interests of individuals, only in consistency with the public benefit. The design of their institution is to encourage virtue, to protect good men, to frown upon the courses of the wicked, and to repress the fraud and injustice, by which oppressors consume the faithful of the land, and devour the widow and him who hath no helper.

Our Apostle would teach the civil authority, that the great objects of their care, are to cherish virtue, and extirpate vice; to avenge public and individual wrongs; to curb the excesses of selfish avarice and ambition, and to foster that philanthropy and integrity, by which alone, nations can be built up and established. And they would do well to remember, that not only the general welfare of the community is a principal object with all rulers who pursue the end of their appointment, but that god requires of them, a constant and watchful attention to the happiness of the church of Christ; and for this plain reason, that magistrates can in no way so substantially promote the public good, as by honoring the doctrines and followers of Jesus. Whatever infidel wits may dream to the contrary, Jesus Christ is appointed by the Father to a universal kingdom. For the Father hath committed all judgment to the Son: And gave him to be head over all things to the Church. By him Kings reign, and at his pleasure he sets up and casts down all human rule and authority. And those are short sighted politicians, who pay no special regard to Christ. As the Governor of all States, he will be acknowledged Supreme, sitting in the assemblies of the mighty, and judging among the God’s: States that have heard of Christ, and his exaltation, and give him no public acknowledgments, are profanely impious against the Father and the Son, and may well fear the wrath of the Lamb. Let rulers then receive their power, as proceeding from Christ, and by solemn testimonies of respect to him and to his disciples, honor him as their Sovereign: And thus kiss the Son, lest he be angry and they perish from the way. They are ordained for the particular benefit of the Church, for the prosperity of which, all the wheels of Providence, and all the revolutions of empire, have been in motion from the morning of time. It should lie upon the minds of rulers, especially of those who make a profession, that they believe the truth of the Christian religion, to honor Christ by a true profession, and an answerable life, and by their immediate regards in all their administrations, to the prosperity and dignity of Christ’s family upon earth. This is God’s governing end in their appointment to rule, that his children may lead peaceable and quiet lives in godliness and honesty. It is a gross mistake, an affront upon the Lord of all worlds, to affirm, that civil magistrates have nothing to do for the church of Christ: Their paramount Sovereign, their civil trust, without a diligent attention to his church upon earth. As well may the minister of an earthly Prince allege that he has nothing to do for the peace and dignity of his master’s family, as civil rulers can allege that they have no concern with the church, the family of the King of Zion. The magistrates most assiduous and unwearied labors are due by his appointment to the church of God.

Our attention is called under the next head, to specify,

1st, to be the minister of God for good, the ruler must entrain an ardent love for his people.

Love is the main spring of every interchange of kind offices amongst men. In no case has this Divine principle a more efficacious operation, than when the ruler’s heart is inspired with a paternal affection towards his subjects. To be the father of his people, is the magistrate’s dignity: This constitutes his nearest conformity to our universal Parent: This will animate him to prosecute the common happiness, under all temptations, and in seasons of the most pressing trials and difficulties: Without this, he will faint under the perverseness and ingratitude of his people, when they oppose his labors for their good, and ill requite his faithful and painful services for national establishment and prosperity. Love animated the patience and perseverance of Moses, to plead for Israel in their numerous rebellions, and finally to pledge his own prosperity, for their salvation, when he prayed that God would spare them, altho’ to vindicate his justice, he should blot him out of his book; that is, cut him off from a name and inheritance among the tribes of the Lord, in the land of promise.

This noble affection filled David with all the agonies of distress, and the importunity of prayer, that God would spare the sheep of his flock, from the sword of the destroying Angel, which was drawn over Jerusalem. This fortified Nehemiah, to a life of denial, conflict and danger, while he built the city of his father’s sepulchers. And this will give energy to the endeavors of all magistrates for the prosperity of their brethren, and make them to esteem diligence, watchfulness, personal expense, self-denial, continual humiliation and supplication before God, but reasonable and pleasant services for the public benefit. That he may pursue their prosperity, the ruler must cultivate a tender and benevolent affection for his people. Again,

2nd, to be God’s minister for good, the ruler must learn the characters and interest of his people.

Ignorant and uninformed Statesmen, however honest in their intentions, can do very little for the happiness of the community. Their limited views create local prejudices, and subject them to the artifices of interested politicians. While a part of the community make undue advantages of their ignorant mismanagement, the body languishes and withers away for want of counsel, energy and uniformity in the civil administration. It concerns rulers, therefore, to be well acquainted with the tempers, capacities, views and interests of the citizens, in all parts of their government, that they may adapt their administration to the advantage of the whole, without material injury to individuals. Rulers unacquainted with the interests of the several professions, and the reputation and capacities of the principal characters, will make grievous mistakes in government, by confining their labors to a narrow circle, and by losing the services of the most suitable men in the community. What is more preposterous, than for rulers to exert their influence and authority, for the partial interest of the territory in their vicinity, to make the interest of one class or profession yield to the avarice and ambition of another; to be a stickler for this or that faction in the State? A ruler should have an enlarged heart, a noble, well-instructed mind; able to comprehend the characters and interests of his brethren, and disposed, with a generous impartiality and dissuasive benevolence, to speak peace to all his seed. And for this end he must study the dispositions, the employments, the weaknesses and abilities, and the substantial interests of all his subjects. This knowledge is essentially requisite to be a useful and reputable magistrate. Again,

3rd, to be a minister for good to the people, the ruler must be instructed in the political maxims and laws of the State, in which he governs.

The safety of a people, especially of a free people, depends upon a sacred adherence to the original principles of their government. When those principles are disregarded, every blessing is insecure, and the administration degenerates into an arbitrary despotism. Therefore rulers should understand the system of laws, and those forms of administration, to which the people are accustomed, and conform themselves to those original principles; then they will have a line of conduct in their office, and the people will know what to expect from them. As a general knowledge of civil policy is necessary to make an accomplished ruler, so a thorough acquaintance with their own state policy is necessary to make a tolerable one. When ignorance is in place, the people will mourn, and folly and wickedness be exalted on every side. It was an essential qualification for government in Solomon, that God had given him wisdom of heart, very much, even as the sand upon the sea-shore. WO to thee, O land, when thy King is a child. The curse of ignorant uninformed rulers is taught us by the prophet Isaiah, and I will give children to be their Princes, and babies shall rule over them: As for my people, children are their oppressors, and women rule over them: O my people, they which lead thee, cause thee to err. And faith Solomon, the Prince that wanted understanding, is also a great oppressor. But by wisdom and understanding the throne is established, and the expectations of the people are richly gratified. No man therefore, should undertake to rule amongst men, until he is fully instructed into the civil constitution and laws of the community, where he is to govern. Again,

4th, to promote the public good, rulers must be controlled in all their measures, by truth and integrity.

For wisdom without integrity, will soon degenerate into cunning and artifice, by which the interests of the community will fall a prey to those who should be their friendly protectors. A magistrate without truth and sincerity is the snare and perdition of his subjects. All power should be founded in truth, both in the attainment and the exercise of it. The lip of truth shall be established forever: but a lying tongue is for a moment. Excellent speech becometh not a fool; much less do lying lips a prince. An administration founded in truth and righteousness, will bear the test of scrutiny: and measures dictated by honesty, shall come forth approved and prosperous in the end: while the duplicity of deceitful politicians shall perish, and involve both rulers and subjects in the snares of perplexity and ruin. All men, especially all leading men, carry their measures with the most success and reputation, when they prosecute them with simple uniformity and honest sincerity. It should therefore be the first object with him who rules over men, to be just, to be true in his administrations: not having a mysterious system of delusion to deceive others into his fraudulent intentions.

To gain the confidence of their subjects, rulers must be men upon who whom they may safely depend. And without this confidence, subjects can derive very little advantage from government. Men in place, therefore, must make declarations and promises strictly just and clearly intelligible, and by adhering to them, the subject must know what to expect from authority. Rulers, to be useful, must deal fairly and honestly with the people; distribute equal justice; protect them from wrongs, and punish injuries with integrity and decision: not leave honest men the prey of fraud.

It is a sad time, when rulers are so inattentive to justice and veracity, that truth falls in the streets, and he who departs from iniquity, makes himself a prey. Good rulers make fair promises and keep them, and are exemplary in fulfilling contracts. The magistrate, who defrauds his subjects, will have a poor face to punish individuals who defraud one another. Do rulers wish to be public blessings? Then let them keep good the public faith, sustain the credit of the state, and pay punctually the public contracts. This will give energy to government, establish the influence and credit of authority, and teach the people that uprightness and veracity, by which alone the various members of society can be closely cemented. A dissembler and a cheat among individuals, is a base character; and a fraudulent administration of government, is a character as much more detestable, as the number and authority of the rulers exceed one individual. Some have acted as though a fraud or falsehood might be lost in the number of partners, or be sanctified by great and powerful names: but he who sitteth in the Heavens, will manifest their error, and prove, that lying lips are an abomination to the Lord, that they are but for a moment, that the feet of unrighteous rulers stand in slippery places; and when the good man seeth their end, he shall suddenly curse their habitation. Does the ruler wish to be useful and reputable? Let him be a true and honest man. Would he involve himself and the community in infamy and perplexity? Let him be unequal in his administrations; let his performances contradict his promises; by false weights and false measures of justice and equity, let him frame iniquity by law, and teach the Lord’s people to transgress. Again,

5th, to rule well, the magistrate must cultivate habits of industry and frugality.

Rulers have so much to do, that they have no time to lose. An indolent ruler, like the useless and unwieldy drone, devours the honey which others have gathered. He consumes the people’s tribute without earning it. The support which subjects should liberally furnish for the maintenance of government, rulers should merit by their diligent services. And while they carefully avoid avarice in withholding expenses for the public good, it concerns them to use the revenues of the State, with economy, that no part of the public treasure be applied to useless and trifling purposes. Covetousness and prodigality are both mischievous vices in rulers, and they should avoid each extreme, if they would be blessings to the people.

Indolent rulers will be other ways vicious. Idleness will cloud their minds and extinguish the nobler sensations of the soul, and the most noxious weeds will spring up in their place. By their example, habits of idleness, intemperance, dissipation, gaming, and profaneness, like some infectious contagion, will spread through all ranks of people. An enervated, poor and contemptible people will be the consequence of an indolent and dissipated administration of government. Such wicked rulers will rule over a poor, worthless people; the community will sink into effeminacy, dependence and wretchedness. It becomes the magistrate then to be a man of business, not a man of pleasure; to be attentive to his office, and painful in his exertions for the common good. Thus shall his example recommend hardiness, patience, frugality and self-denial to his subjects, and through the prevalence of these virtues, they shall be able to meet the enemy in the gate, and rise with luster among the nations. It was the maxim of a Grecian Prince, worthy to be adopted by the Christian magistrate; it ill becomes a Statesman, to sleep all night.

The virtues of industry, and well-judged frugality, are the support of republican governments, and are therefore peculiarly requisite in their civil authority, who by their example, should teach the people habits of diligence, hardiness and economy, not to consume, according to the baneful customs of our republics, in dissipation and luxury, much more than we earn by our labor and industry. Again,

6th, to answer the purpose of their institution, civil rulers must protect good citizens, and punish the wicked.

The scripture character of rulers is that they are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Power is grossly abused and perverted, when wicked citizens are fostered and protected by authority.

God has ordained rulers to avenge the wrongs of injustice and oppression, and the violence of sedition and rebellion. It is only when bad men are in authority, that vile men are exalted and screened from justice. No favor or friendship, no relation or connection with men in power, should cover the wicked from punishment. Rulers are to execute the laws: And the laws are made for the lawless and disobedient. All delays of justice, the exemption from chastisement , which corrupt citizens receive in breaking the peace and violating the ordinances of justice, is a sore malady in the State, and proves that the head is sick and the heart faint. Good magistrates, by their influence, suppress immorality, and every transgression of relative justice. God commands it, and faithful subjects have a claim upon their rulers, to be protected from fraud and oppression, to have the laws executed, their persons, and their liberty and properly protected, from the depredations of designing and unprincipled men. And the magistrate who does not endeavor to punish and reclaim, or utterly to purge from the State wicked and disobedient subjects, forgets the main design of his exaltation. And when good men are left to the fear and danger of losing their privileges and possessions, they are sadly neglected; and the God of Heaven will avenge their quarrel against such slothful and unrighteous magistrates. To let the wicked go unpunished, and the righteous live without protection, is both a contemptible weakness and a scandalous wickedness in authority. For it should be an abomination to Kings to do wickedness, and the throne is established by righteousness. Righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is the reproach of any people. He that justifies the wicked and he that condemns the just, even they both are an abomination to the Lord. For this end rulers wait upon their work to make a clear distinction between the just and the unjust; and it is an illustrious display of benevolence, to over-whelm incorrigible offenders by the arm of power, and raise to safety and honor the faithful of the land. It is a precept grounded upon moral reasons, and consequently of perpetual obligation,– The man that will do presumptuously and will not hearken unto the Priest, which standeth there to minister before the Lord thy God, or unto the judge, even that man shall die; and thou shall put away the evil from Israel. The State must employ punishments adequate to the suppression of vice, and rewards commensurate to the encouragement of virtue and fidelity: and the ruler who permits the rod of the wicked to rest upon the lot of the righteous, is disobedient to God, and an enemy to his people. Again,

7th, Rulers, to be ministers of God for good, must be men of religion.

All Christian graces are of immediate use in the administration of government. And as rulers receive their ordination from God, he expects that as servants they honor him, and obey his Son Jesus Christ, as their liege Lord. Since religion furnishes men with those excelling gifts and good dispositions, which qualify them to govern, so they can never cultivate faith and piety with too careful an assiduity. Their success in office, and their usefulness among their subjects, depends primarily upon the Divine presence and blessing. Therefore they should be men of exemplary faith in their King and Savior, and not lean unto their own understanding. That illustrious magistrate Nehemiah thought it a most essential qualification in his brother Hananiah, to take charge over Jerusalem. Because he was a faithful man and feared God above many. Magistrates should be men of prayer, that God may dwell with them and direct their counsels. They should be accustomed to appear before God in the posture of suppliants, that he would enlighten their ignorance, and prosper their exertions. None have more need of wisdom than they; and to whom should they apply but to give to him who giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not. Would they be honored by the obedience of their subjects? Let them obtain this honor by obeying God, by lives of temperance, sobriety and a becoming gravity. Like their blessed Master, let them be meek, humble and gentle towards all men; like him, love righteousness and hate iniquity, be constant, watchful, and fervent in duty, bearing their sorrows, and relieving the distresses of their fellow men; like him go about doing good. It is incumbent upon them , to honor Christ in his institutions, setting a pattern before their brethren of family religion, resolving with the pious and valiant Joshua, that as for us and our houses, we will serve the Lord; attending uniformly upon the ordinances of public worship, hallowing God’s Sabbaths, and receiving his sanctuary, attentively waiting upon the dispensation of the gospel. From rulers we may well expect submission to all God’s commandments, and that they cherish the appointed means of diffusing Christian knowledge, and by honoring Christ’s ministers and followers, become nursing fathers of the Church. Some have thought that religion is no important part of a ruler’s character: It is true, that rulers without religion are to be obeyed. But when it is considered that they are made rulers ultimately for the good and prosperity of the Church, we must censure those for their ignorance or irreligion, who adopt a maxim so pernicious to civil society, and embarrassing to the interests of virtue and morality. Without religion, rulers have no God, unto whom thy may repair and expect his blessing upon their administration. God is not with them, and when his presence is withdrawn, darkness and perplexity will fill their paths with snares and adversity. Immoral and ungodly rulers may affect courtesy, affability, and patriotism to gain popularity; but they have no moral principle upon which the public may depend, and too often have they proved the scourge of the community, and the rod of God’s indignation against a profane or hypocritical people. Therefore we lay it down as a qualification of great moment to the State, that magistrates be men of piety, who have a governing regard to the glory of God, and a warm affection for the gospel of Christ. Such are the sentiments avowed in our form of government, which requires the great officers of government, before they enter upon their trust, to declare their belief of the Christian religion, as the religion taught from Heaven, for the happiness and salvation of lost men. Again,

8th, to influence them to a useful discharge of their trust, it is important, that rulers keep in mind their mortality and their future account before the bar of God.

I have said ye are Gods: and all of you are children of the Most High. But ye shall die like men. Like their brethren of the dust they shall go to the grave, the house appointed for all the living. To death succeeds their solemn account at the tribulation of the son of man, who will judge the secrets of men according to our gospel. The wise, the great and the mighty of the earth, will stand before the impartial judgment-seat, upon a level with the despised and indigent of their subjects. At that solemn hour when the opinions of men shall be lighter than the dust of the balance, and the flattering tongue shall be put to perpetual silence, when the judgment shall be the Lord’s and shall be administered without respects of persons, the enquiry will be, not whether we have been great in the earth, enjoyed the applauses of our fellow worms, and exercised dominion among the sons of the dust: but whether we have filled our station, kept in view our last account, and prepared matters for our acquittal at the solemn trial. Rulers should remember that their reward will be in exact proportion to their benevolence and fidelity, not according to their power and authority; and that their punishment will be alleviated by any instances of present impunity from the importance of human justice: but according to their sloth and luxury, their wantonness and ambition, their oppression and avarice, such will be their retribution from the sentence of the Lord of Saboath, who hears the groans of injured and neglected subjects, and has prepared a strange punishment for the haughty oppressors of the earth.

Were the day of retribution, which will soon overtake us all, duly realizes by magistrates, how could they fail to discharge with assiduity and care their sacred trust, and to be in earnest to become ministers of God for good, to the people? Having stated the methods, by which rulers may answer the benevolent purposes of Heaven in their appointment, it concerns us under the last general head,

I have finished my doctrinal observations; may I be indulged in some practical reflections, and sundry cursory observations upon the present situation of this Commonwealth, and the methods which god requires to be pursued for restoring and lengthening out our tranquility, and then conclude with addresses suited to this important occasion. As I have endeavored in the whole, so in this branch of discourse I would with to speak with the unfettered freedom of a Servant of that Prince, whose kingdom is not of this world.

This country was planted by men of singular piety, of whom the old world was not worthy. God found them a refuge from the oppression of civil and spiritual tyranny. Having planted, he protected them from the most pressing dangers. Often hath he delivered them by signs and wonders, and by an out-stretched arm. In some feeble measure our Forefathers lived worthy of the Divine care over them, and by grateful obedience acknowledged the salvations wrought for them. But their children forgot his benefits, and by irreligion and sensuality, by dissipation and luxury, by worldliness and pride, they provoked the Holy One of Israel, to threaten them with the loss of those privileges and blessings, which he had so richly bestowed, and they had so unthankfully abused.

Many have celebrated the virtues, and confidently predicted the rising glories of the American States. But while we continue our provocations, we may do well to enquire, whether these flattering panegyrists do not speak to us smooth things, and prophecy deceit? Would not the sublime prophet Isaiah address us in another stile? ”Hear O heavens, and give ear O earth! For the Lord hath spoken. I have nourished and brought up children, and they have rebelled against me. Ah sinful nation, a people laden with iniquity, a seed of evil doers, children that are corrupters, they have forsaken the Lord, they have provoked the Holy One of Israel unto anger, they have gone away backward. Because the Lord was wroth with his heritage, he did of late raise up adversaries unto them of their brethren. The British parliament, in support of a groundless claim, levied an unnatural war against us, and assumed without warrant to be the Highest Powers in our governments.

By the will of God, and the direction of his ordinance, our civil authority, to whom our first allegiance was due, we were called to contend for our possessions, our liberties, and our lives, even unto blood. Long and distressing was the conflict. In the confusions of war, and especially in the perplexities of such a war, in which the minds of the people were divided as to their duties of allegiance, order and government were essentially injured among us, and the spirit of subordination and loyalty, which was before habitual, was nearly lost, and for a season we were threatened with all the miseries of that people, who have no magistrate to put them in fear. But in the season of our declensions, He who remembered mercy for his people, interposed for our help, and in due time ordained peace for us. But in nothing was his grace more remarkable than in leading us out of a distempered state of partial anarchy into a state of order and government. He gave us laws and testimonies right and good, a civil constitution perhaps the most perfect in the world, which is the security of good citizens, the admiration of the wise, and the envy of tyrants: To which if we strictly adhere, we cannot in a political sense, fail of being a happy people.

Since this mercy of our God upon us, in saving us from the evils of war, and plucking us from the confusion of anarchy, we have walked unworthy of his great goodness. We sang his praises, but soon forgot his benefits. We have continued to those follies and excesses, for which he had already chastised us. While deeply involved in debt, our distempered passion for the fashions of luxurious and affluent nations plunged us into our former prodigality and unprofitable expenses. Instead of applying ourselves to discharge the claims of public and private creditors, and thus to vindicate our honor and independence, we employed the riches of our soil in purchasing the trappings of an exotic dress, and in indulging our vitiated appetites in the expensive productions of distant regions, and thus are we become the servants of foreigners, and strangers rule over us. Poor and dependent, our minds are enervated to the pursuits of a national freedom and dignity. And yet restless under the unavoidable pressure of our follies, we are little inclined to satisfy our creditors, and pay the price of our beloved dissipation. Like the prodigal, exhausted and worn down by riot, we complain of our pains and embarrassments, and idly resolve into a grievance, that poverty, from which no created power but our own can save us. Jaded by our devices, indigent through profuse living, rendered intractable by long exemption from the restraints of human and Divine laws, and proud in a licentious liberty, that fore-runner of despotism, we have become restless under necessary burdens, and with a mistaken resentment, have complained of public requisitions as the source of our sorrows and perplexities. Lavish expenses have made us poor, and a temper not duly subordinate, has turned our complaints from our own follies, against our Fathers, our best friends and benefactors. How many of us have labored to free ourselves from the necessary burdens of public and private debts, that we might obtain a wider scope for the indulgence of appetites, which it were much better to mortify?

Will the enquiry be thought immodest, when I ask, whether our wealthy and leading characters have not been first in this transgression? Of the legislators of our republican government, we might have expected effectual laws to discourage excesses, by which the citizens are so certainly degraded to a state of servility and dependence. They knew better than their constituents, the evil of such excesses. Might they not in due season, have encouraged industry, temperance and frugality, among the people; laid restrictions upon foreign luxuries, and made it as necessary as it was useful, for the people to produce the accommodations of life by their own labor, and upon their own soil. And especially might not the examples of men in power, and families of fashion and affluence, in preferring the productions of our own country, to commodities received from abroad, have produced the most salutary effects among all classes of our citizens? Such examples would have been more influential and authoritative, than a whole code of commercial regulations. This is one of our wounds: I mention it freely, since I hope in good Providence, that our rulers, our public teachers and the multitude of our brethren, will think it important to apply themselves to a radical cure of the evil. For nothing kills the noble spirit of freedom, like the state of dependence, which will ever attend the folly of spending more than we earn. Let our rulers not merely in word, but indeed, by a laudable example, be first in this matter, and teach republicans to be honest, industrious and frugal in their modes of living. Then shall substantial wealth and independence be the joyous portion, of all classes of our happy citizens.

That we have been transgressors in many moral and Christian duties, the god of judgment hath testified, in the calamities brought upon us. To punish and to reclaim us, he hath sent among us the rod of his visitation. Shall there be evil in the city, and the Lord hath not done it?

The last year, a year equally distinguished for the gifts of Providence, and for our unthankfulness and disobedience to human and Divine authority, has been fruitful in new and perplexing evils. God has suffered a spirit of insurrection and resistance of lawful authority to rise up in this Commonwealth. As a correction from him, it is a righteous testimony of his holy displeasure; as proceeding from man, perhaps an opposition to government, and a war against the community, has been seldom more wanton and unprovoked. The objects sought after, in these tumults, have been of the most faulty kind. One avowed end was to compel the Legislature into an emission of a paper currency, to be a tender in payment of all public and private contracts. A measure wholly preposterous, when the public ought to be discharging their old obligations, and not contracting a new debt by borrowing money by an emission of paper; a measure totally unjust, and as truly impolite as to administer opiates to cure a lethargy. The faultiness of such violent attempts arose also from the utter impossibility in the present state of our affairs, that the Legislature could make a promise upon their paper and keep it; that is, they could never honestly redeem the money, by saving it from a rapid depreciation, and making punctual payment. Such a measure then would have been a gross violation of commutative justice, the unwavering observance of which is enjoined upon all bodies of men under all possible circumstances. To endeavor by hostility to compel the Legislature into a measure, which they wisely thought impolitic, and knew to be palpably unjust, was a high-handed offence, and clearly proves, that multitudes were under the clouds of God’s anger, and were sadly forsaken of restraining grace.

But the design was filled with other mischiefs. It was to wrest from the Legislature the power of governing; from the tribunals of law the power of decreeing justice; and from the Executive, the essential prerogative of carrying into effect the laws of the Commonwealth. Thus were our foundations to have been destroyed. The declared intentions of the male-contents, and what they attempted by levying an impious war upon their country, was to arrest the arm of government, and seize the administration of a despotic rule into their own hands; to sap the foundations of our glorious constitution, to change its essential forms, and thus to break down the barriers of our rights, and overwhelm this great republic in dreary confusion and irretrievable ruin. Whoever has been acquainted with their complaints and their claims, and has been a witness of their proceedings, will consider this, as a charitable representation of their views and pursuits.

Blessed be the Lord god of our salvation, that in the midst of our unworthiness and provocations, he has interposed and saved us from the sword of the oppressor, and the violence of the wicked men. Ardent thanksgivings are this day due to the Father of mercies, that in the season of alarming dangers, he raised up an administration of government, who, in the faithful page of history, will be celebrated for their wisdom, their moderation and integrity.

After many outrageous and treasonable excesses, had prevailed, in several parts of the State, and the lives and estates of the guilty authors were forfeited to their country, our Chief Magistrate, at the request of the Legislature, offered a free and full pardon to all the promoters and abettors of those seditious tumults. Through an infatuated obduracy, that pardon was scornfully rejected, even under the clearest light and evidence exhibited to them, that their complaints were groundless, and that the government had been administered with great integrity. Former violences were renewed, the criminal demands of the insurgents increased, and the existence of the Commonwealth, was put to the hazard. When unmixed mercy could not reclaim bur raised to higher excesses the resistance of the offenders, authority assumed a more firm and decisive tone, and raised a military force to repel their violence: Yet great as the forbearance and compassion of the government in all their exertions to suppress the rebellion. Forgiveness was still extended to the body of the rebels; the leaders only were left to the justice of the law, and even with the leaders much lenity was used by proffering terms of pardon to many of them. The steps of our civil administration were the marks of their justice and humanity. The wisdom and decision of the Council demand our admiration and gratitude: the measures of our Chief Magistrate all denoted the firmness of his spirit, his regard for our laws, his inflexible adherence to the principles of the constitution, and his unshaken determination to protect his country, and repress the violence of wicked men. His conduct was equally distinguished for benignity and moderation, that aversion from bloodshed and that ardent wish to recover and preserve offenders, which is a shining part of the character of a good man and a Christian magistrate. He hath shewed himself the Father and Friend of his country: The minister of God for good to his people.

That worthy personage, who acted under his immediate orders in suppressing the public commotions, has added fresh laurels to his former honors, and evinced how much he deserves the appellation of the Christian Hero. The officers and men employed in this important and unwelcome service, by their firm, temperate and wise conduct, discovered that excellent spirit which ought ever to reign in the bosoms of free citizens. Ye authors and leaders of these happy operations, if we forget your services, let our right hand forget its cunning. Thou country thus saved of the Lord from the horns of the unicorn, if we do not remember thee above our chief joy, let our tongue cleave to the roof of our mouth.

Thrones of judgment are established, and the fear of violence is drive from us: and by the uninterrupted execution of our wholesome laws, we may sit quietly under our own vines and under our own fig-trees. And we may gladly hope that without connivance from men of influence, these seeds of sedition will e’er long be totally eradicated from our republic: The methods of Providence in protecting the Commonwealth and succeeding the measures of government, merit particular notice and unfeigned gratitude. The finger of God has been conspicuous in directing and prospering our public counsels. Operations dictated by wisdom and moderation, have been succeeded by remarkable interpositions of Heaven. The hearts of those in rebellion melted like wax, and they could perform no part of their enterprise; and the measures of administration were crowded with the wishes for success.

May the author of all effectual influences impress the minds of deluded citizens with a conviction of the criminality of their conduct, and of the evident hand of God, which was lifted up against them. It is but justice to observe, that the measures of government, have been conformable to the system of God’s government over a sinful world. Mercy has been freely proffered, and when despised, has been followed by a mixture of judgment and mercy. Because the Lord loved his people, he hath inclined the hearts of their rulers into such a prosperous and salutary administration. To regard these foot-steps of Providence, and pursue a similar system of administration, can scarcely fail to recover us from our confusions, and establish our public tranquility. But inattention to the finger of God, and an abuse of his healing mercies, the continuance of our rebellious and resistance of his civil ordinance, will provoke him to empty us from vessel to vessel, and for the iniquities of our land, many will be the rulers thereof, unstable as water we shall not excel. But if conscious of past ingratitude and abuse of blessings, we will turn unto him by repentance and works of righteousness, will speak the truth one to another and love as brethren; if our rulers will go before us in the duties of prayer, faith and obedience, submission to Christ, and respect to his doctrines and institutions; if they will love the people and consult their interest by integrity and goodness, study rather to do them good than to gratify their idle humors; if they will measure their administrations by the line of truth and honesty, although thousands frown,; if they will be temperate and industrious in their work, will punish the wicked and protect obedient subjects, and thus set the Lord always before their face, then shall their reputation flourish and their authority prove an unspeakable blessing to the people: God shall fill Zion with judgment and righteousness, and wisdom and knowledge shall be the stability of our times and strength of salvation: And the fear of the Lord shall be our treasure; and shall lift us high among the nations.

The time calls me to a conclusion, in suitable addresses.

Our first attention is due to our worthy Chief Magistrate, called by God and his country to the chair of government.

May it please your Excellency,

THAT happy tranquility which we enjoyed under your former administration, cannot fail to excite our congratulations, that God has so far restored your health, that you are able to accept the chief Magistracy in this Commonwealth. Appointed by God to bear the rule over your brethren, you will be pleased to accept our best wishes that your health may be adequate to the weighty burthens of your high and sacred office. Our prayer to the almighty is, that he would be the health of your countenance and your God; that he would strengthen you to eminent usefulness among the people. May divine preservation and illumination accompany your administrations that you may continue to act worthily for Christ our King, and be accepted of the multitude of your brethren. May that diffusive love which you so early manifested for your country, by placing yourself in the first rank of danger s, to repel foreign usurpation, and vindicate the privileges and laws of your country still animate you, to pursue the happiness of the community, by supporting the dignity of civil authority, the prerogatives and independence of the Supreme Executive, and the other branches of administration; by making law terrible to all invaders and usurpers of the powers of government, and by drawing aa line of distinction between faithful subjects, and those who may be so lost to virtue, as to disturb the public peace, and assail the property, the liberties and the lives of their fellow-citizens.

With pleasing anticipation, we behold your Excellency God’s minister for good, bearing the sword of the State, not as a terror to good works, but to the evil. Our eye with delight marks your path, while you lead us your children into the duties of relative of relative and Christian life, and by your example teach us, that self-denial, frugality and industry, so essential to the happiness of a free people. From your Excellency, will our Legislature expect advice in those measures, which may maintain inviolate the principles of our civil constitution against every species of encroachment; how the public good is to be pursued, honesty and integrity, diligence and application encouraged, and dissipation driven from the State; how the laws of justice may be effectually vindicated, and the seat of fraud and oppression, be removed far from us. Our expectations are from your Excellency, that liberty shall be maintained by law, and all subjects be secure in their possessions; that public faith, and national credit and dignity, be solicitously preserved.

May the institutions of literature flourish under your friendly patronage; especially may that illustrious university to which the public is so much indebted for laying the foundation of science in your Excellency, and qualifying you for such extensive services in this, and through the United States, be the object of your peculiar care, and by your powerful influence be protected in all its important rights and immunities.

We hope in the goodness of the universal Parent, that by affording you his presence and grace, he will shew, that because he loved his people, he hath therefore appointed you to rule over them. From your Excellency, the interests of piety and the Christian religion justly expect continual aid and friendly countenance. May the Angel of the Divine presence, enlighten and beautify the paths of your administration. In your days, religion, truth and peace dwell on the earth, and after you have served your generation by the will of God, may you receive the rewards of your fidelity, from the approbation of your Judge. May you here enjoy a portion, better than many sons, and late be welcomed to the presence of your Divine Savior and Judge, and from him obtain that Crown of glory which fadeth not away.

Our respects are now due to the Gentlemen who compose the Honorable the Senate, and the Honorable the House of Representatives.

Fathers of our country, and Elders of our tribes,

YOU are this day, constituted by Jesus Christ, the ordinance of God, for the god of his church, and the sacred principles of our excellent constitution: a constitution which wisdom will approve, as the national bulwark of our independence and sovereignty, the effectual protection of good citizens, the security of freedom, property and life, and our defense against the rude encroachments of anarchy and despotism. You have this day declared your belief of the Christian religion. Integrity in this profession will lead you to prize our constitution the more, since it is so friendly to morality, and the Christian faith. You have bound yourselves in the discharge of your office, to promote the common good upon gospel principles, by cultivating in your temper, and practice, those benevolent graces of Christianity, which will enable you to rule with reputation to yourselves, and advantage to the people. You have pledged yourselves to honor Christ’s institutions, to protect his servants, to discountenance all contempt of the doctrines and maxims of his holy faith. Thus from the manner of your inauguration, we may expect, that you may be nursing Fathers to the Church. It becomes a minister of that church,(and will therefore be acceptable to you) to stir up your pure minds to use the gift that is in you, for the good of the people. YOU ARE THE Ministers of God, and as such, accountable at the tribunal of the Son of Man, in the great day of dread decision. Let me exhort you as candidates for eternity, to keep in mind that solemn day, and as faithful servants, to be habitually prepared for it. And that through Divine grace, you may give up a good account at last, be entreated to regard the eye of God, which is upon you, and look to him to pardon your unworthiness, to counsel you by his unerring wisdom, and to quicken you by his truth: that he would not take his Holy Spirit from you, but by his effectual influences, guide you into the paths of uprightness. The scriptures will teach you your liableness to error; and your desire to be useful. Will excite your applications for that anointing of the Holy One, by which you will not err fatally. As Rulers, it concerns you to be men of prayer, to maintain an intercourse with Heaven, and a humble dependence upon Divine teaching and guidance. Do you wish to be honored of God in your office? You must honor him by submitting your administrations to his government, by a respect to his name, his institutions and those eternal laws of righteousness, ordained for the careful observance of all his rational subjects. With you the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom, and to depart from evil is understanding.– To you as their Fathers , will the people look for patterns of moral and Christian duty. You will therefore go before them in personal, in family and public religion and obedience. Care for the State will arm your zeal and fortitude against vicious and immoral practices, to frown upon gross breaches of human and divine laws. Your services will be approved of God, and useful to the community, whenever you shall punish with decision and impartiality, the lawless practices of vicious and disobedient subjects. Through your example and official exertions shall those virtues of benevolence, integrity, industry and frugality, so essential to a republican and Christian community, greatly prevail. And your testimony shall suppress the insolence of fraud and injustice, falsehood and perjury, by which the bonds of society are dissolved. May the oath of God become terrible, and all human promises and contracts be held sacred. Punctuality in Rulers to their contracts is the first step towards a general honesty in the State. Their example gives energy to laws against private fraud and injustice. You will feel the bond of that law of your Master, to owe no man anything; but according to the ability of the people, to make a punctual and satisfactory payment of public debts. You will utterly disallow all measures, which may put honest and feeble citizens into the power of griping and unprincipled oppressors; than such measures, nothing is more repugnant to that Gospel, by which you are to be judged. Every indirect method to extricate the people from embarrassments is a new load to sink them in the mire. The Fathers of our tribes will therefore cultivate public and private faith, and teach us all not to go neighbor beyond, or to defraud our neighbor.

May the good God influence our honorable Legislature, into a system of administration, which shall defend our Constitution, render venerable our laws, protect from violence the seats of Justice and the Throne of Judgment, and by a due mixture of mercy and justice, allure offenders to obedience, or by adequate penalties incapacitate them from disturbing the public tranquility. You will think nothing too much to encourage a spirit of loyalty and patriotism; and to this end you will encourage the means of grace and education. To your wisdom does it belong to discover the political measures, for promoting the good designs which have been mentioned, but I may suggest, that they should be such as are approved by the gospel of Christ.

OUR national concerns, as a confederated Republic, are serious concerns. Your deliberate counsels will be requisite to invent some remedy for our national imbecility and reproach. Unless effectual and liberal measures are soon taken, our glory and independence will vanish into air. Be entreated Fathers, to lay aside limited views and local prejudices, and to encompass the Union in exertions of your wisdom and patriotism.

THE better to answer the ends of your appointment, you will consider it highly important, in filling up the vacancies in the Legislature, and in constituting a Council for His Excellency, to choose faithful and approved men, who fear God and obey Christ above many, men of noble minds, superior to intrigue, and unfettered by faction, or independent sentiments, who abhor covetous practices, men whose circumstances are not embarrassed, and who will not fear to do the thing which is just, who love the people, and will by personal labors and self-denial, and unwearied diligence, pursue their solid and lasting advantages, and yet disdain by meanness and artifice, and by sacrificing their own judgment, to gain an empty popular applause.

A Legislature thus constituted, and what a respectable number of such amiable and worthy characters do I now behold; such a Legislature, shall in the issue enjoy the blessings of their country, while time serving politicians, shall sink in the dirt of their deserved ignominy: Such a Legislature may hope to have God with them, to prosper the work of their hands. From the faithful discharge of an earthly trust, they shall in their time and order, be received to the plaudit of their final Judge. Such is the reward which we pray that every member of our public administration, in the Executive, Legislative and Judicial department, may now deserve, and in future obtain from the mouth of him, who sits upon the Throne.

MAY we all repent, and do our first works, that God may be in the midst of us. That he may sit in the assembly of our Rulers, is the devout supplication of all, who hope in his mercy, and wish well to this Commonwealth.

BLESSED art thou O land, hen thy King is the Son of nobles, and thy Princes eat in due season. Happy is that people, that is in such a case; yea happy is that people, whose God is the Lord.

Thus with sincerity, and as well as I was able, have I spoken unto you the Lord’s message. May the effectual co-operations of the Blessed Spirit, render the truths which have been delivered, useful to this whole Assembly, and by the consequent fruits may it appear, that in very deed God has been among us. And when we shall severally stand in the great congregation of the assembled universe, by a precious holy life, may we be prepared to be found of our Judge in peace.

First, Jefferson did not coin the phrase. It was introduced in the 1500s by leading clergy in England who objected to the government taking control over religious doctrines and punishing religious activities and expressions. In America, many famous early ministers also used the phrase – all well over a century before Jefferson did.

First, Jefferson did not coin the phrase. It was introduced in the 1500s by leading clergy in England who objected to the government taking control over religious doctrines and punishing religious activities and expressions. In America, many famous early ministers also used the phrase – all well over a century before Jefferson did. Third, on multiple occasions, Jefferson called his state to Christian prayer and worship. In 1774, he called for a day of fasting and prayer,

Third, on multiple occasions, Jefferson called his state to Christian prayer and worship. In 1774, he called for a day of fasting and prayer,  That 1797 treaty was one of several that America negotiated with Muslim nations during America’s first War on Islamic Terror (1784-1816),

That 1797 treaty was one of several that America negotiated with Muslim nations during America’s first War on Islamic Terror (1784-1816),

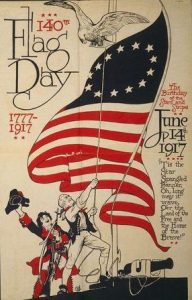

June 14th is Flag Day which commemorates the day in 1777 when the Continental Congress passed a resolution “that the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

June 14th is Flag Day which commemorates the day in 1777 when the Continental Congress passed a resolution “that the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth- that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that “except the Lord build the House they labor in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without His concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel.

I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth- that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that “except the Lord build the House they labor in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without His concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel.

The signers of the Declaration of Independence pledged their “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” so that they and their posterity (us!) could enjoy both spiritual and civil liberties to a degree unknown in the world at that time. That pledge literally cost many of them their lives and fortunes. Some of the 56 signers who sacrificed much include John Hancock, Robert Morris, and John Hart. Richard Stockton was another who paid a great price.

The signers of the Declaration of Independence pledged their “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” so that they and their posterity (us!) could enjoy both spiritual and civil liberties to a degree unknown in the world at that time. That pledge literally cost many of them their lives and fortunes. Some of the 56 signers who sacrificed much include John Hancock, Robert Morris, and John Hart. Richard Stockton was another who paid a great price.

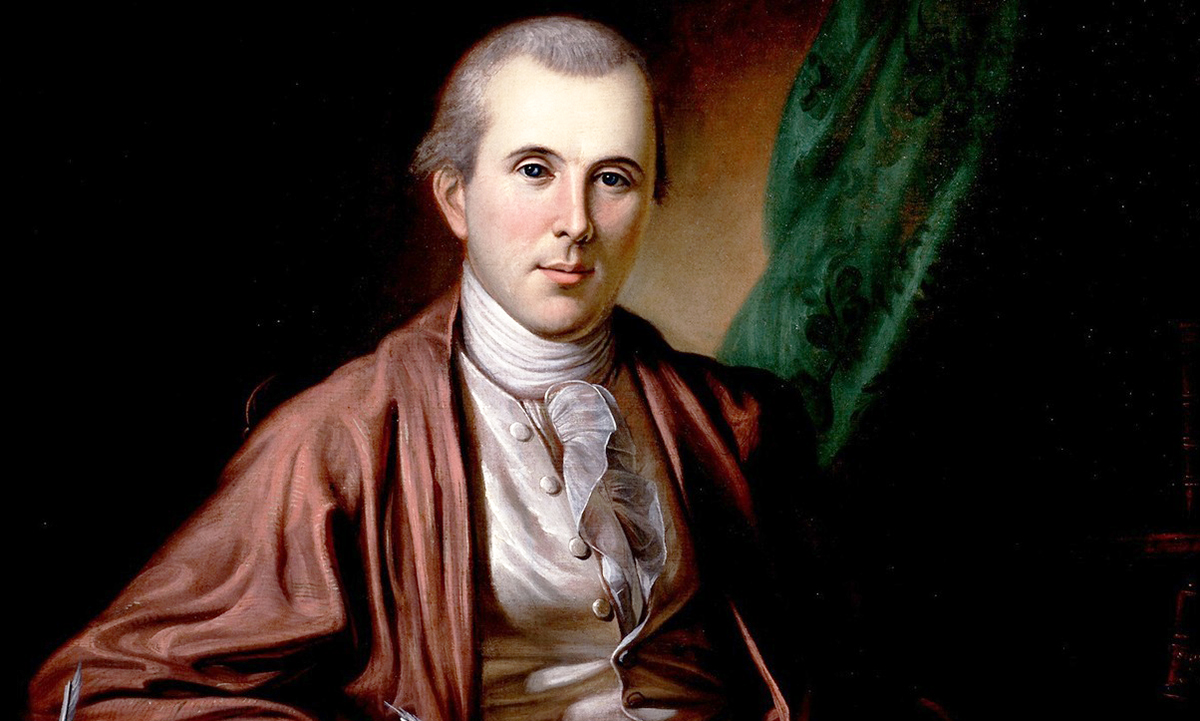

WallBuilders mission is “presenting America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on our moral, religious, and constitutional heritage.” Two of our great heroes largely forgotten today include Dr. Benjamin Rush (signer of the Declaration, who John Adams considered as one of America’s three most notable Founders

WallBuilders mission is “presenting America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on our moral, religious, and constitutional heritage.” Two of our great heroes largely forgotten today include Dr. Benjamin Rush (signer of the Declaration, who John Adams considered as one of America’s three most notable Founders  Elisha was active in the patriot cause

Elisha was active in the patriot cause

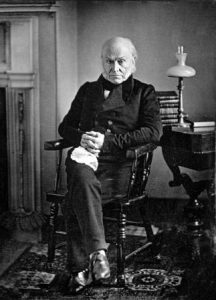

If you answered John Quincy Adams (the earliest serving President to have a photograph taken of him), then you were right!

If you answered John Quincy Adams (the earliest serving President to have a photograph taken of him), then you were right!

Shortly after John Quincy’s death on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1848, those nine letters were quickly printed as a book for all of America’s youth,

Shortly after John Quincy’s death on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1848, those nine letters were quickly printed as a book for all of America’s youth,

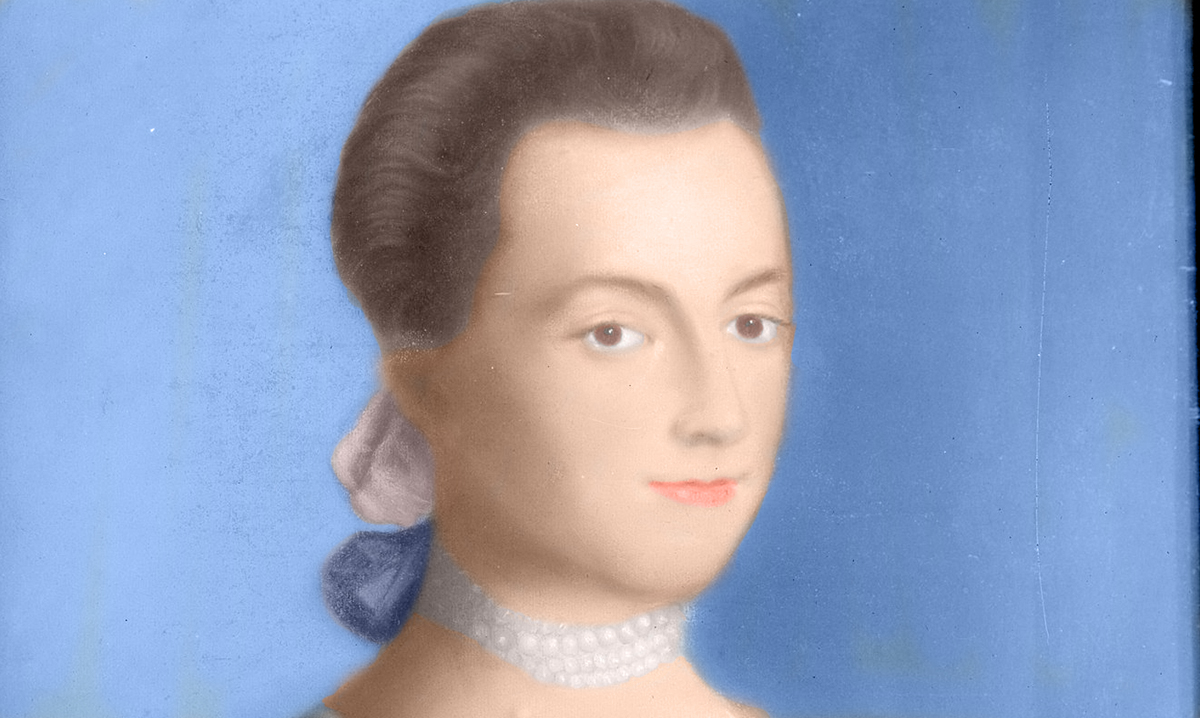

Around that time, she also wrote her close friend, Mercy Otis Warren, America’s first female historian who is called “The Conscience of the American Revolution,” and similarly told her:

Around that time, she also wrote her close friend, Mercy Otis Warren, America’s first female historian who is called “The Conscience of the American Revolution,” and similarly told her: You have seen how inadequate the aid of man would have been if the winds and the seas had not been under the particular government of that Being Who “stretched out the heavens as a span” [Isaiah 40:12], Who “holdeth the ocean in the hollow of His hand” [Isaiah 40:12], and “rideth upon the wings of the wind” [Psalm 104:3]. . . . The only sure and permanent foundation of virtue is religion. Let this important truth be engraven upon your heart. And also that the foundation of religion is the belief of the only one God, and a just sense of His attributes as a Being infinitely wise, just, and good, to Whom you owe the highest reverence, gratitude, and adoration; Who superintends and governs all nature, even to clothing the lilies of the field [Matthew 6:28] and hearing the young ravens when they cry [Psalm 147:9]; but more particularly regards man, Whom he created after His own image [Genesis 1:26], and breathed into him an immortal spirit [Genesis 2:7], capable of a happiness beyond the grave.

You have seen how inadequate the aid of man would have been if the winds and the seas had not been under the particular government of that Being Who “stretched out the heavens as a span” [Isaiah 40:12], Who “holdeth the ocean in the hollow of His hand” [Isaiah 40:12], and “rideth upon the wings of the wind” [Psalm 104:3]. . . . The only sure and permanent foundation of virtue is religion. Let this important truth be engraven upon your heart. And also that the foundation of religion is the belief of the only one God, and a just sense of His attributes as a Being infinitely wise, just, and good, to Whom you owe the highest reverence, gratitude, and adoration; Who superintends and governs all nature, even to clothing the lilies of the field [Matthew 6:28] and hearing the young ravens when they cry [Psalm 147:9]; but more particularly regards man, Whom he created after His own image [Genesis 1:26], and breathed into him an immortal spirit [Genesis 2:7], capable of a happiness beyond the grave.

The right . . . of bearing arms . . . is declared to be inherent in the people. Fisher Ames, A Framer of the Second Amendment in the First Congress

The right . . . of bearing arms . . . is declared to be inherent in the people. Fisher Ames, A Framer of the Second Amendment in the First Congress