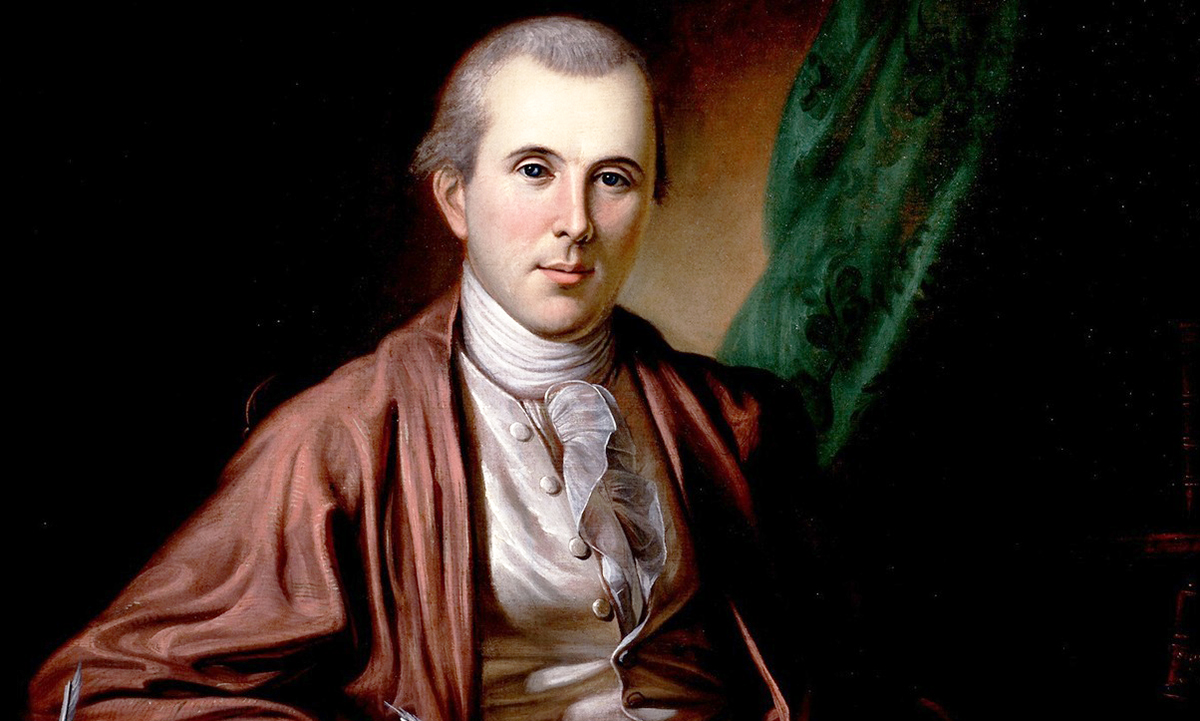

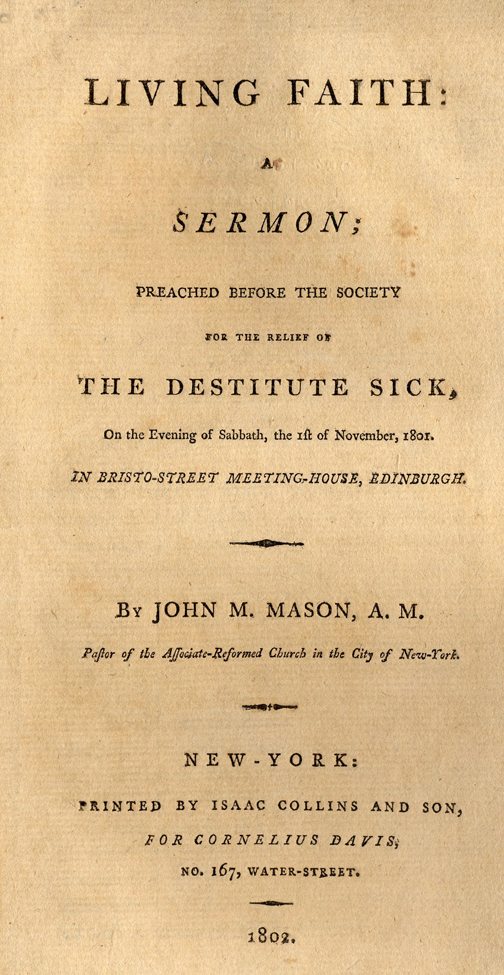

John Mitchell Mason (1770-1829) was a minister from New York. He received a doctor of divinity degree from Princeton University in 1794 and was a pastor of two churches in New York City during his lifetime. Mason founded the first seminary of the Associate Reformed Church, in New York City (1804), was president of Dickinson College (1821-1824), and was a trustee (1795-1811) and provost of Columbia College (1811-1816). This sermon was preached by him in 1801.

A

SERMON;

Preached Before The Society

For The Relief Of

THE DESTITUTE SICK,

On the Evening of Sabbath, the 1st of November, 1801.

IN BRISTO-STREET MEETING HOUSE, EDINBURGH.

By JOHN M. MASON, A.M.

Pastor of the Associate-Reformed Church in the City of New-York.

ACTS XV. 9 compared with GAL. V. 6.

PURIFYING THEIR HEARTS BY FAITH, — FAITH WHICH WORKETH BY LOVE.

The church of Christ, chosen out of the world to bear his cross and to partake of his holiness, has, from the very nature of her vocation, many obstacles to surmount, and many foes to vanquish. A warfare, on the issue of which are staked her privileges, her consolations, her everlasting hope, opens an ample field for exertion, and ought to concentrate her strength and wisdom. Unhappily, however, controversies about things which do not involve her substantial interests, have, at all times, interrupted her peace and married her beauty. Weakness, prejudice, and passion found their way into the little family of the Master himself; and, even after the descent of the Spirit of truth, invaded and violated his sanctuary. Disputes concerning the Mosaic ritual had arisen among Christians to so great a height, and were conducted with so much ardour and so little love, that the power of godliness was in danger of being stifled in a contest about the form, and the Head of the church deemed it necessary to interpose his rebuke. “Whether ye are called Jews or Gentiles; whether ye observe or neglect some formulas of the typical law, are not questions which should kindle your animosities and exhaust your vigours. A more awful subject claims your enquiries. While you are occupied in vain jangling, the winged moments are hurrying your should to their eternal state. Are you ready to depart? Is your title to the kingdom clear? Pause, listen, examine. In Christ Jesus neither circumcision availeth any thing, nor uncircumcision; but a new creature; but a faith of the operation of God; but a faith which purifies the heart and the works by love.”

To us, my brethren, not less than to those early professors of the cross, is the heavenly oracle addressed. We, too, have our weakness, our prejudices, our passions, which often embark us in foolish and frivolous litigation. We, too, have immortal souls of which the whole world cannot repay the loss, and which are hastening to the bar of God’s righteousness. Come then, let us endeavour to collect our wandering thoughts; to shut out the illusions of external habit; to put a negative on the importunities of sense, and try whether our religion will endure the ordeal of God’s word. If our faith is genuine, it purifies the heart, and works by love. Precious faith, therefore, in its effects upon spiritual character; that faith which draws the line of immutable distinction between a believer and an unbeliever, and without which no man has a right to call himself a Christian, is the subject of our present considerations. And while the treasure is in an earthen vessel, may the excellency of the power be of God!

Before we attempt to analyse the operations of faith, we must obtain correct views of his nature.

Some imagine it to be a general procession of Christianity, and a decent compliance with his ceremonial. They accordingly compliment each other’s religion and are astonished and displeased if we demur at conceding that all are good Christians who have not ranged themselves under the banners of open infidelity.

Others advancing a step farther, suppose that faith is an assent to the truth of the gospel found on the investigation of its rational evidence. — without asking what proportion of the multitudes who profess Christianity have either leisure, or means, or talents for such an investigation, let us test this dogma by plain fact. Among those legions of accursed spirits whom God has delivered into chains of darkness to be reserved unto judgment, and their miserable associates of the human race, who have already perished from his presence, there is not one who doubts the truth of revelation. Men may be skeptics in this world, but they carry no skepticism with them into the bottomless pit. They have their rational evidence which is impossible to resist; evidence shining in the blaze of everlasting burnings, that every word of God is pure. That faith, then, by which we are saved, must be altogether different from a conviction however rational, which is yet compatible with a state of perdition. If any incline to set light by this representation, as taking the advantage of our ignorance, and retreating into obscurity which we cannot explore, let him open his eyes on the common occurrences of life. He may see, for there is not even the shadow of concealment, he may see both these good Christians of fashion, and these good Christians of argument, without God in the world — He may see them betraying those very tempers and pursuing those very courses by which the bible describes the workers of iniquity— He may see them despising, reproaching, persecuting that profession and practice, which, if the Scriptures are true, must belong to such as live godly in Christ Jesus. Of both these classes of pretended Christians the faith is found to be spurious, and at an infinite remove from the faith of God’s elect; for in neither of them does it purify the heart, or work by love. The Scriptures teach us better.

As faith, in general, is reliance upon testimony, and respects solely the veracity of the testifier; so that faith which constitutes a man a believer before God, is a simple and absolute reliance upon his testimony, exhibited in his word, on this solid and SINGLE ground, that he is the God who cannot lie. It was not a process of reasoning, which riveted in Abraham’s mind the persuasion that in his seed all the nations of the earth should be blessed, and procured him the appellation of the father of the faithful. It was an act of NAKED TRUST in the Veracity of his covenant-God, not only without but above, and against the consultations of the flesh and blood. Abraham BELIEVED GOD, believed him in hope, against hope; and it was counted to him for righteousness. It is the same at this hour. The mouth of the Lord hath spoken it — must silence every objection, and cut short every debate. And they who do not thus receive the Scriptures, cannot give another proof that they believe in God, as a promising God, at all.

The testimony of God which faith respects, comprising the whole revelation of his will, centers, particularly, in the free grant which he has made of his Son, the Lord Jesus Christ, to sinners of the human race; assuring them, that whosoever believeth on him shall not perish, but shall have everlasting life; that he will be a father unto them and they shall be his sons and his daughters; that he will dwell in them, and walk in them, and be their God, blessing them, and walk in them, and be their God, blessing them, in their precious Redeemer, with all spiritual and heavenly blessings. Now that faith after which we are inquiring, consists precisely in “receiving and resting upon Christ Jesus for salvation, as he is offered to us in the gospel,” that is, in the testimony of his Father.

This faith is not the creature of human power. It is a contradiction to suppose that men can argue themselves, or be argued by others, into a reliance upon the testimony of God. Because this implies a spiritual perception of his eternal veracity ¨whereas the reason of man is corrupted by sin, and the natural tendency of corrupted reason is to change the truth of God into a lie. Nothing can rise above its own level, nor pass the limits of its being. It were more rational to expect that men should be born of beasts, or angels of men, than that a principle of life and purity should be engendered by death in a mass of corruption: and carnal men are DEAD in trespasses and sins. Cast it, therefore, into the fairest mould; polish, and adorn it with your most exquisite skill, that which is born of the flesh will still be flesh; weak, corrupt, abominable: enmity against the law of God, and, if possible, more rank enmity against the gospel of Jesus Christ. From this source it is vain to look for faith in his blood. We must seek it higher.

It is of divine original. A gift which cometh down from the Father of lights: By grace are ye saved, through faith, and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God.

It is of grace — For it is one of those covenant mercies which were purchased by the Saviour’s merit, and are freely bestowed for his sake. It is given us, on the behalf of Christ, to believe on his name.

Of grace — Because it is a fruit of the gracious Spirit. As Jehovah the Sanctifier, he creates and preserves in the soul. For this reason he is called the Spirit of faith, which is, therefore of the operation of God.

I. It purifies the heart.

Human depravity is a first principle in the oracles of God. From within, out of the heart, proceed those evil thoughts, and evil word and evil deeds, which defile, disgrace, and destroy the man. And he who refuses to admit the severe application of this doctrine to himself has not yet arrived at the point from which he must set out in a course of real and consistent piety. He may, indeed, flatter himself in his own eyes until his iniquity be found to be hateful, but who shall ascend into the hill of God? or who shall stand in his holy place? He and he only, who has clean hands, and a pure heart. Now, as it is the grace of faith by which a sinner obtains that purity which qualifies him for the fellowship and kingdom of God, we are to inquire, In what the purity of the heart consists? and what is the influence of faith in producing it?

The heart is a term by which the Scriptures frequently express the faculties and affections of man. As the pollutions of sin have pervaded them all, they all need the purification of grace.

At the head of the perverted tribe stands a guilty confidence. Stern, gloomy, suspicious it cannot abide the presence of a righteous God; and yet lashes the offender with a whip of scorpions. To render the conscience pure, pardon must intervene and shelter it from that curse which rouses both its resentments and its terrors. This is effected by the blood of the covenant, which, speaking better things than the blood of Abel, sprinkles the heart from an evil conscience.

The will is purified, when it is delivered from its rebellion against the authority of God, and cordially submits to his good pleasure. This, too, is from above: For his people are made willing in the day of his power.

The understanding is purified, when its errors are corrected, and the mists of delusion dissipated. When its estimate of sin and holiness; of things carnal and things spiritual; of time and of eternity, corresponds with the sentence of the divine word. This also is from above. The eyes of our understanding are enlightened, that we may know what is the hope of his calling, and what is the riches of the glory of his inheritance in the saints; and what is the exceeding greatness of his power to us-ward who believe.

In fine, the affections are purified when they are diverted from objects trifling and base, to objects great and dignified. When they cease to be at the command of every hellish suggestion, and every vagrant lust — When they add to the crucifixion of those profligate appetites in the gratification of which the ungodly man places his honour, his profit, and his paradise, their delight in a reconciled god, as the infinite good — When they aspire to things above, where Jesus Christ sitteth at God’s right hand; breathe after his communion; and are disciplined and chastened as becometh the affections of a breast which the Holy Ghost condescends to make his temple. —Such affections are surely from heavenly inspiration: for thus faith God, I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean; from all your filthiness and from all your idols will I cleanse you. A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you; I will take away the stony heart out of your flesh, and I will give you a heart of flesh.

While the purification of the heart, thus explained from the Scriptures, is the work of the divine Spirit, it is accomplished by the instrumentality of faith. For he purifies the heart by faith. Under his blessed direction, the grace of faith possesses a double influence.

1. As a principle of moral suasion, 1 it presents to the mind considerations the most forcible and tender for breaking the power of sin, and promoting the reign of holiness. The presence, the majesty, the holiness of god — the sanctity of his law — his everlasting love in the Lord Jesus — the affecting expression of the love in setting him forth to be propitiation for sin — The wonders of his pardoning mercy — The grace of Christ Jesus himself in becoming sin for them, that they might be made the righteous of God in him— The condescension of the Holy Ghost, who designs to well in them as their Sanctifier — The genius of their own peace , their brethren’s comfort, and their Masters glory — These, and similar motives which arise from the exercise of precious faith, operate mightily in causing believers to walk humbly with their God. The love of Christ constraineth us, even as a rational inducement, to live henceforth not unto ourselves, but unto him that died for us and rose again. And while a graceless man is deterred from the commission of crime, not by a regard to God’s authority, or by gratitude for his loving-kindness, but by calculations of prudence, or fear of penalty, a Christian acting like himself, repels temptation with a more generous and filial remonstrance, How can I do this great wickedness and sin against God!

But, brethren, I should wrong the Redeemer’s truth and enfeeble the consolations of his people, were I to confine the efficacy of faith in purifying the heart to the influence of motive. I have not mentioned its chief prerogative; for,

2. Faith is that invaluable grace by which we have both union and communion with our Lord Jesus Christ. In the moment of believing, I become, though naturally an accursed branch, a tree of righteousness, the planting of Jehovah that he may be glorified: I am no longer a root in a dry ground, but am planted by the rivers of water, even the water of life, which proceedeth out of the throne of God, and of the Lamb. — I am engrafted into the true vine, and bring forth fruit in participating of its sap and fatness. — I am made a member of the body of Christ, of his flesh, and of his bones; so that the Spirit which animates his body pervades every fibre of my frame as one of its living members. His vital influence warms my heart. Because he lives, I live: Because he is holy, I am holy: Because he hath died unto sin, I reckon myself dead unto sin. This is the fruit of union.

Communion with him is properly speaking, a common interest with him in his covenant-perfection. The benefits of his communion flow into the would in the exercise of faith. Whatever Jesus has done for his people, (and their sanctification is the best part of his work,) he conveys to them in the promise of the gospel, and that promise is enjoyed in believing. It is by faith that I live upon the Great God my Saviour, and make use of him as Jehovah my strength. By faith I am privileged to go with boldness into the holiest of all, and, be it reverently spoken, to press my Father in heaven with reasons as strong why he should sanctify me, as he can address to me why I should endeavour to sanctify myself. Lord, am I not thine? the called of thy grace? redeemed by the blood of thy dear Son? Hast thou not pledged thy being, that none who come to thee in his name shall be rejected? Is it not for thy praise that my heart be purified, and I made meet for walking in the light of thy countenance among the nations of the saved. Wilt thou leave me to conflict alone unaided, unfriended, with my furious corruptions, and my implacable foes? Wilt thou, though entreated for thy servant David’s sake, refuse to work in me all the good pleasure of thy goodness and the work of faith with power? I cannot, will not let thee go except thou bless me. Such faith is strong; it is omnipotent; it lays hold on the very attributes of the Godhead, and brings prompt and effectual succor into the laboring spirit. This is the reason why it purifies the heart. I know, that to such as have never been brought under the bond of God’s covenant, I am speaking unintelligible things. Blessed be his name, that continuing carnal, ye cannot understand them. If ye could, our hope would be no better than your own. But I speak to some whose burning souls say Amen to the doctrine, and rejoice in the consolation; who, in the struggle with corruption and temptation, have cried unto God with their voice, even unto god with their voice, and he heard their cry; and bowed his heavens and came down; gave them deliverance and victory; and shed abroad in their bosoms the serenity of his grace. — these are precious demonstrations of his purifying their hearts by faith.

It is obvious, that the fruits of faith, which have been now enumerated, cannot be exposed to the eye of the worldling. Deposited in the hidden man of the heart, they are privileges and joys with which no stranger intermeddles. Shall we thence conclude, that the faith from which they spring is unsusceptible of external proof, and never extends its benign influence beyond the happy individual who possesses it? By no means. This would be and Error too gross for any but the theoretical religionist. The text ascribes it to a social effect: For,

II. It does not more certainly purify the heart, than it worketh by love.

Love is the master-principle of al good society. It is the holy bond which connects man, the angel with angel, and angels with men, and all with God. It is itself an emanation from his own purity. For God is love : and he that dwelleth in love, dwelleth in God, and God in him. Consequently the new man, whom regenerating grace creates in elected sinners, and whose activities are maintained by faith, must be governed by love. Its first and most natural exercise is toward that God who hath loved them with an everlasting love, and therefore with loving –kindness hath drawn them. It is the apprehensinon by faith of Jehovah’s love to them in Christ, anticipating them with mercy, forgiving them all trespasses, loading them with covenant-favour, which softens their obduracy, melts them into tenderness, and excites the gracious re-action of love toward their reconciled Father. We love him, says an apostle who had drunk deeply into the spirit of his Master, we love him, because he first loved us.

As an enemy to God is, by the very nature of his temper, an enemy to himself and to all other creatures, so one in whose heart the love of God is shed abroad by the Holy Ghost, not only consults his own true happiness, but is led to consult the happiness of others. Charity, faith the apostle Paul, suffereth long and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vauneth not itself; is not puffed up; doth not behave itself unseemly; seeketh not her own; is not easily provoked; thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; beareth all things; believeth all things; hopeth all things; endureth all things. The Scriptures, indeed mark love to the brethren as the great practical proof of our Christianity. Nothing can be more peremptory than the language of the beloved disciple — If a man say, “I love God,” and hateth his brother, he is a LIAR: for he that loveth not his brother whom he hath seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen? On this point however, there will be little dispute. Men are instinctively led, to measure, by their social effects, all pretensions of love to God. The question before us, and of which the scriptural decision will be far from uniting the mass of suffrage, is how faith works by love?

The apostle asserts, that the faith of a Christian, instead of being a merely speculative assent to the abstract truth of the gospel, is an active moral principle, which cannot have its just course without embodying itself in deeds of goodness. The reasons are many and manifest — By faith in Christ Jesus, we are justified before God, our natural enmity against him is slain, and his love finds access to our hearts. By faith we embrace the exceeding great and precious promises, and, in embracing them, are made partakers of the divine nature; so that we are filled with all of the fullness of God; and out of the abundance of the heart, not only does the mouth speak but the man act : By faith we converse with our Lord Jesus Christ; and are conformed to him; follow him in the regeneration; and learn to imitate that great example which he left us when he went about doing good. By faith we obtain the promised Spirit who sanctifies our powers both of mind and body, so that we yield our members instruments of righteousness unto God. By faith in Christ’s blood, which redeems us from the curse of the law, we are also liberated from the vassalage of sin: for the strength of sin is the law; and receiving the law is fulfilled and satisfied by his righteousness, come under its obligation in his covenant, and are enabled to keep it by his grace. Now the fulfilling of the law, is love; love and kindness to God and our neighbor, in all our social relations : It is, therefore, impossible that faith should not work by love.

All the directions of the book of God, for the practice of the moral virtues, consider them as the evolution of the principle of love residing in a heart which has been purified by faith. Our Lord’s sermon on the mount, by the perversion of which many have seduced themselves and others into a lying confidence in their own fancied merits, was preached not to the promiscuous multitude, but to his disciples, who professed faith in his name. And the scriptures of the apostles, especially the apostle of the Gentiles, follow the same order. They address their instructions to the church of God — to the saints — to such as have obtained like precious faith with themselves. Not a moral precept escapes from their pen, till they have displayed the riches of redeeming love. But when, like wise master-builders, they have laid a broad and stable foundation in the doctrines f faith, they rear, without delay, the fair fabric of practical holiness. — It is after they have conducted their pupils to the holiest of all, through the new and living way which Jesus hath opened, that you hear their exhorting voice, Mortify, therefore, your members which are upon the earth; fornication, uncleanness, inordinate affection, evil concupiscence, and covetousness which is idolatry. — Put off also all these, anger, wrath, malice, blasphemy, filthy communication out of your mouth. Lie not one to another, seeing ye have put of the old man with his deeds, and have put on the new man which is renewed in knowledge after the image of him that created him; where there is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision; barbarian, Scythian, bond nor free; but Christ is all and in all, put on therefore, as the elect of God, (for this very reason ye are his elect,) holy and beloved put on the bowels of mercies, kindness, humbleness of mind, meekness, long-suffering, forbearing one another, and forgiving one another if any man have a quarrel against any, even as Christ forgave you, so also do ye. And above all these things, above bowels of mercies, above kindness, above humbleness of mind, above meekness, above long-suffering, above forbearance, above forgiveness, above all these things, put on CHARITY which is the bond of perfectness. If the apostles, then understood their own doctrine; or rather, if the spirit, by whom they spake knows what is in man, we are not to look for real love, i.e. for true morality, from any who are not the children of God by faith in Christ Jesus. And, on the contrary, this faith is the most prolific source of good actions; because it purges the fountain of all action, and sends forth its vigorous and healthful streams, purifying the heart and working by love.

I should be unfaithful, my brethren, to truth you, were I to dismiss this subject without employing its aid for repelling an attack which is often made upon the Christian religion — for refuting the calumny which pretended friends have thrown upon its peculiar glory, the doctrine of faith — for correcting the error of those who, separating faith from holiness, have a name to live, and are dead—and for stimulating believers to evidence, by their example, both the truth of their profession, and power of their faith.

The enemies of the gospel have invented various excuses for their infidelity. At one time there is a defect of historical document: at another, they cannot surrender their reason to inexplicable mystery. Now, they are stumbled at a mission sanctioned by miracle: then, the proofs of revelation are too abstracted and metaphysical: and presently they discover, that no proof whatever can verify a revelation to a third person. But when they are driven from all these subterfuges: when the Christian apologist has demonstrated that it is not the want of evidence, but of honesty; that it is not an enlightened understanding, but a corrupted heart, which impels them to reject the religion of Jesus, they turn hardily round and impeach its moral influence!! They will make it responsible for all the mischiefs and crimes; for all the sorrows, and convulsions, and ruins which have scourged the world since its first propagation.

Before such a charge can be substantiated, the structure of the human mind must be altered; the nature of things reversed; the doctrine of principle and motive abandoned forever. It is only for the forlorn hope of impiety to engage in an enterprise so mad and desperate. Say, Can a religion which commands me to love my neighbor as myself, generate or foster malignant and murderous passions? Can a religion which assures me, that all liars shall have their part in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone, encourage a spirit of dissimulation and fraud? Can a religion which requires me to possess my vessel in sanctification and honour, indulge me in violating the laws of sexual purity? in breaking up the sanctuary of my neighbours peace? in throwing upon the mercy of Scandal’s clarion the fair fame of female virtue? Can a religion which forbids me to be conformed to this world, cherish that infuriate ambition which hurls desolation over the earth, and fertilizes her fields with the blood of men? Can a religion —— But I For bear —— From whence come wars and fightings among you? Come they not hence, even from your lusts? Those very lusts from which it is the province of faith to purify the heart. The infidel pleads for his unholy propensions on the pretext that they are innocent, because they are natural: And when a thousand curses to himself and to society follow their indulgence, he charges the consequence upon a religion which enjoins their crucifixion, and which to give them their career, he trampled under foot. But stop, vain man! Was it the religion of Jesus Christ, which, on its first promulgation, breathed out threatenings and slaughter? Shut up the saints in prison? Punished them oft in every synagogue? Compelled them to blaspheme? And, being exceedingly mad against them, persecuted them even unto strange cities? Was it the religion of Jesus Christ which in its subsequent progress, illuminated the city of Rome with the conflagration of a thousand stakes, consuming by the most excruciating of deaths, a thousand guiltless victims? 2 Was it the religion of Jesus Christ which, at a later period, when the Tiber overflowed, or the Nile did not overflow; when the earth quaked, or the heavens withheld their rain; when famine or pestilence smote the nations ordered its opposers to the lions? 3 Was it in obedience to the religion of Jesus Christ, after the expulsion of pagan idolatry, at the mother of harlots and abominations of the earth became drunk with the blood of the saints and with the blood of the martyrs? Was it the religion of Jesus Christ which, after being rejected with marks of unexampled insult, suggested to the knights-errant of blasphemy, the project of regenerating the world by the power of atheistical philosophy? Was it this religion which taught them to blot out the great moral institute of society, the Sabbath of the Lord? To extinguish the best affections of the human heart, to break asunder the strongest ties of human life, and to subvert the basis of human relations, by exploding the marriage-covenant. This, which instigated them to offer up hecatombs of human sacrifices to every rising and every setting sun? to hew down, with equal indifference, the venerable matron and her hoardy lord; the vigorous youth the blooming maid, the sportive boy, and the prattling babe? And while they were thus writing the history of their philosophical experiments in the blood of the dead and the tears of the living, to boast the victories of their virtue? But my soul sickens —Ah no! the wisdom which cometh from above, that wisdom which the gospel teaches, is first pure, the peaceable, gentle, and easy to be entreated; full of compassion and of good fruits; without partiality, and without hypocrisy. Such was its imposing aspect in the primitive ages. “Give me a man,” said a celebrated father of the church, the eloquent Lactantius, “give me a man passionate, slanderous, ungovernable: with very few words of God I will render him as placid as a lamb. Give me a man greedy, avaricious, penurious: I will give him back to you liberal, and lavishing his gold with a munificent hand. Give me a man who shrinks fro pain and death; and he shall presently contemn the sake, the gibbet, the wild beast. Give me one who is libidinous, an adulterer, a debauchee; and you shall see him sober, chaste, temperate. Give me one cruel and blood-thirsty; and that fury of his shall be converted into clemency itself. Give me on addicted to injustice, to folly, to crime; and he shall, without delay become just, and prudent, and harmless.” 4

Similar, in proportion to its reception by faith, are still the effects of this blessed gospel. What has exploded those vices which though once practiced even by philosophers, cannot now be so much as named? What has softened the manners, and refined the intercourse of men? What is it which turns any of them from sin to God, and makes them conscientious, humble, pure, though at the expence of ridicule and scorn from the licentious and the gay? What has espoused the cause of suffering humanity? Who explores the hospital, the dungeon, the darksome retreat of unknown, unpitied anguish? The infidel philosopher? Alas, he amuses himself with dreams of universal benevolence, while the wretch perishes unheeded at his feet : and scruples not to murder the species in detail, that he may promote its happiness in the gross! On his proud lift of general benefactors, you will look in fain for the name of a Howard; and in their system of conduct your search will be equally fruitless for the traces of his spirit. Christianity claims, as her own, both the man and his principles. She formed his character, sketched his plans, and inspired his zeal. And might the modesty of goodness be overcome; might the sympathies of the heart assume visible form; might secret and silent philanthropy be called into view, ten thousand Howards would issue, at this moment from her temples; from the habitations of her sons; from the dreary abodes of sickness and of death. Tell me not of those foul deeds which have been perpetrated in her name. Tell me not that her annals are filled with the exploits of imposture and fanaticism : that her priests and her princes have been ambitious, profligate, and cruel : that they have bared the arm of persecution, and shed innocent blood upon the rack and the scaffold; at the stake and in the field : that they have converted whole nations into hordes of banditti, and led them, under the auspices of the cross, to pillage and massacre their brethren who boasted only the “simple virtues” of pagans and infidels. The question is not what actions her name has been abused to sanctify, but what have accorded with her principles, and are prompted by her spirit? It is no discovery of yesterday, that Satan is transformed into an angel of light; and therefore no great thing if his ministers also be transformed into ministers of righteousness. Ignorance and dishonesty have borrowed a Christian guise for the more successful practice of knavery and rapine. But when they have violated all the maxims of the Christian religion; when they have contemned her remonstrances, and stifled her cries; shall they be permitted to plead her authority? Or shall the scoffer insult her with the charge of being their accomplice and adviser? No! In so far as men do not study whatsoever things are true, honest, just, pure, lovely, and of good report, they evince not the power of faith, but the power of unbelief; in other words, not the spirit of the gospel, but a spirit directly opposed to it; i. e. the spirit of infidelity. If, then, you think to justify you incredulity by shewing a man, who to a profession of Christianity adds a life of crime, the indignant gospel tears the mask from his face, and exposes to your view the features of a brother. Whatever be his profession, we disown his kindred; he acts wickedly, not because he is a Christian, but because he is not a Christian. His crimes conspire with his hypocrisy to prove him and infidel.

Here we must part with some who have cheerfully accompanied us in the detection and reproof of avowed unbelievers. For I am to employ the doctrine of the text for refuting the calumny which pretended friends have thrown upon the peculiar glory of Christianity, the doctrine of faith.

Multitudes, and would to God that none of them were found among the teachers of religion, multitudes who profess warm zeal for revelation, are yet hostile to all those cardinal truths which alone render it worthy of a struggle. Omitting the mockery of such as call Christ Lord, Lord, while they rob him of every perfection which qualifies him to be the Saviour of sinners, let me call your attention to those whose enmity is particularly directed against the doctrine that has been preached to you this evening. Nothing, to use their own stile, can exceed their veneration for religion in general; but if you venture to speak of the righteousness of the Son of God “imputed to us, and received by faith alone;” if you insist on the desperate wickedness of the heart, and the necessity of Almighty Power to regenerate and cleanse it; if you rejoice in the blessedness of that union with the Lord Jesus which places you beyond the reach of condemnation; so that neither death nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature shalt be able to separate you from his love, or shut you out of his kingdom, you must expect to pass, with rational Christians, for a weak though perhaps well-meaning enthusiast; nay, you must expect to hear those blessed truths which are the life of your soul, stigmatized as relaxing the obligations of the moral law; as withdrawing the most cogent motives to obey its precepts : as ministering incentives to all ungodliness. Impossible! Nothing but ignorance of the grace of God in its saving energy, could give birth or aliment to such a slander. It proceeds on the supposition that a sinner may be pardoned, and not sanctified; that he may be delivered from his penalty, and yet retain an unabated affection for his lusts. Were this the fact; did faith in Christ’s blood set him free from the condemning authority of God’s law, and yet leave him under the tyranny of sinful habits, there is no doubt, that it would encourage him to work all uncleanness with greediness. But the reverse is true. The blood of Jesus Christ, applied by faith, does not more certainly abolish guilt, than it paralyzes lust. He is made of God unto us, in a connection which nothing can dissolve, wisdom, and righteousness, and SANCTIFICATION. Our old man is crucified with him, that the body of sin might be destroyed, that henceforth we should not serve sin. The grace of faith is the leading faculty of that new man, which after God is created in righteousness and true holiness. Holiness is the proper element of a believer, as sin is the proper element of an unbeliever. And, therefore, although the notion of grace may be abused to licentiousness, the principle never can; for it is that principle from which we learn to deny ungodliness, and worldly lusts, and live soberly, righteously, and godly, in this present world. To insinuate, then, that the doctrine of free and plenary justification by faith in Christ Jesus, tends to licentiousness, is to give the lie direct to the testimony of the Holy Ghost, and to the uniform experience of his people. Whoever cherishes such an opinion however highly esteemed by himself or by others is not a Christian : he is in the gall of bitterness and in the bond of iniquity. But there is no cause of wonder. The natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God, for they are foolishness unto him. It has been so from the beginning; and will continue so to the end. The objection which he makes, at this hour to the doctrine of grace, is as stale as it is unfounded. It is the very objection which was combated by the apostle Paul. What shall we say then? exclaimed his adversaries, when he preached justification by faith through the imputed righteousness of the Lord Jesus, and the absolute certainty of being saved from wrath through him in virtue of believing, what shall we say then? shall we continue in sin that grace may abound? Or, in modern language, Does not this doctrine of your tempt men to throw the rein upon the neck of their passions, by removing the fear of condemnation and especially by furnishing them with the pretext, that the more they sin, the more is grace exalted in their pardon, seeing that where sin hath abounded, grace doth much more abound? The apostle admits, that the depraved heart is prone to draw such a conclusion, and that it was actually drawn by his enemies : who took occasion from it to represent him as making void the law. But he repels it with the most indignant reprobation. God forbid! the inference is absurd. How shall we that are DEAD to sin, LIVE any longer therein? That doctrine, therefore, which wicked men never accused of leading to licentiousness, is NOT the doctrine of God’s word. That doctrine, on the contrary, against which, by misrepresenting it, they bring this accusation, is the very doctrine of the apostle. But is true and only effect, which we maintain, which the Scriptures teach, and which all believers experience and exemplify, is, that sin shall not reign in their mortal body, that they should fulfill it in the lusts thereof.

Of the same nature and from the same source with the calumny which I have endeavoured to refute, is the practical error4 of many who, separating faith from holiness, have a name to live, and are dead. The error must be rectified, for it is fatal. Some console themselves with their doctrinal accuracy, while their hearts and conduct are estranged from moral rectitude. They hope that their faith, however inactive shall save them at last. Others, in the opposite extreme, disregarding faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, trust in their upright intentions and actions. They know little of what Christians call believing, but they are good moral men. Their Gospel is the trite and delusive aphorism,

“He can’t be wrong, whose life is in the right;”

not considering that

He can’t be right, whose faith is in the wrong.

They talk, indeed, on both sides, with much familiarity, of “our holy religion,” as if its best influences had descended upon themselves. Holy religion it is: But what made it yours? One of you does not pretend to have RECEIVED Christ Jesus the Lord; the other, notwithstanding his profession, has no solicitude to WALK in him: and both are equally far from the salvation of God. Jesus Christ is the way, the truth, and the life; no man cometh unto the Father but by him: No man entertains good thoughts, or performs good works, without being a partaker of his holiness. Every plant which his heavenly Father hath not planted, shall be rooted up. At the great day of his appearance to judge the world in righteousness, no virtue will be approved which did not grow upon his cross, was not consecrated by his blood, and nourished by his Spirit. Such virtues, however they may be applauded here, are only brilliant acts of rebellion against him, and will not, for one moment reprieve the rebels from the damnation of hell. Nor let those whose belief does not purify the heart, nor work by love flatter themselves that their condition is better, or that their doom shall be more tolerable. Whatever judgment shall be measured to others, they who know their Lord’s will, and do it not shall be beaten with many stripes. Be not deceived. The threatening bears directly upon you. You possess to know God, but in works you deny him. Your inconsistency reproaches his truth, and causes his enemies to blaspheme. You lay stumbling-blocks in the way of the unwary. You multiply the victims of that very infidelity against which you declaim: and in as far as they have been seduced by your example, their blood shall be required at your hands. For yourselves, if you die without being renewed in the spirit of your minds, your faith will not save you. The farce of a mock profession will terminate in the tragedy of real and everlasting woe. Oh, then while it is called TO-DAY harden not your hearts! To sinners of every class and character, the forgiveness of God is preached. From his throne in heaven the Saviour speaks this evening. Unto you, O men, do I call and my voice is to the sons of men! Hearken unto me, ye stouthearted, that are far from righteousness: behold I bring near my righteousness. In him is grace, and peace, and life. Now therefore, choose life that ye may live. And may his blessed Spirit visit you with his salvation, creating in you that faith which purifies the heart, and works by love!

Finally, Let Christians be admonished by the doctrine of my text to evince, in their behavior both the truth of their profession and the power of their faith.

They cannot too often nor too solemnly repeat the question of their Lord, What do ye MORE than others? It is not enough for them to equal, they must excel, their neighbours. They have mercies, motives, means, peculiar to themselves. They have a living principle of righteousness in their own hearts; and, in their great Redeemer, they have, as the fountain of their supply, all the fullness of the Godhead. It is but reasonable that much should be required of them to whom much is given. Let your whole persons, O believers, be temples of God. Set your affections on things above, where Jesus Christ sitteth at his right hand. Remember, that every one who hath the hope of seeing Jesus as he is, purifieth himself even as he is pure. Walk in love as he hath loved you. Let this amiable grace shed her radiance over your character, and breathe her sweetness into your actions. Compel, by her charms, the homage of the profane. Cleave not to earth, because your treasure is in heaven. Make use of it to exercise the benevolence of the Gospel, to glorify your Father who is in heaven, to diffuse comfort and joy among the suffering and disconsolate. To do good and to communicate forget not : for with such sacrifices God is well pleased. This evening presents you with an opportunity of shewing that faith worketh by love. The society, on whose account I address you, carry, in their very name, a resistless appeal to the sentiments of men and of Christians. Devoting their labours to “the relief of the DESTITUTE SICK,” they have sought out and succoured, not here and there a solitary individual; but scores and hundreds, and thousands of them that were ready to perish. Sickness, thought softened by the aids of the healing art, by the sympathy of friends, and by every external accommodation, is no small trial of patience and religion. But to be both SICK and DESTITUTE is one of the bitterest draughts in the cup of human misery. Far from me be the attempt to harrow your feelings with images of fictitious woe. Recital must draw a vail over a large portion of the truth itself. I barely mention that the mass of sorrow which you are called to alleviate, appears in as many forms as there are affinities among men.

Is there in this assembly a father, the sons of whose youth are stay of his age, and the hope of his family? In yonder cell lies a man of gray hairs, crushed by poverty, and tortured by disease. His children scattered abroad, or have long since descended into the tomb. The sound of “Father,” never salutes his ears : He is a stranger in his own country : His only companions are want and anguish.

Is there a wife of youth encircled with domestic joys? or is there one whose heart, though solaced with a thousand outward blessings, calls back the aching remembrance of the loved relation? Behold that daughter of grief. The fever rankles in her veins. She has no partner, darer than her own soul, on whose bosom she may recline her throbbing head. Her name is Widow. Desolate, forsaken, helpless, she is stretched on the ground. The wintry blast howls through her habitation and famine keeps the door.

Is there a mother here whose eyes fill in the tenderness of bliss, while health paints the cheeks of her little offspring, and they play around her in all the gaiety of infantine simplicity? I plead for a mother, the toil whose hands was the bread of her children. The bed of languishing destroys her strength and their sustenance. “The son of her “womb” turns pale in her feeble arms; her heart is wrung with double anguish while, unconscious of the source of his pain, he cries for bread and there is none to give it.

Is there here a man of public spirit who exults in the return of Plenty and of Peace? Let him think of those who suffer under the stern arrest of hunger and disease. Ah! Let him think that this wretchedness belongs to the wife and family of the soldier who has fought the battles of his country. The messenger of peace arrives: The murmur of the crowd swells into ecstasy: Their shout echoes through the hills. She raises her drooping head and hears, not that her friend and helper is at hand, but that herself is a widow, and her children fatherless. The blood of her husband and of their father has flowed for the common safety — He shall never return.

Is there a Christian here, who knows how to do good unto all, but especially to them that are of the household of faith? Among these afflicted who are sinking under their infirmities, and have not where to lay their heads, are some whom the celestials minister, and who are fellow-heirs with Christ in glory. I state these facts: I use no arguments: I leave the result with your consciences, your hearts, and your God.

This institution was formed in the year 1785, for the special purpose of relieving those who are disabled by sickness from following the occupations by which they provide for themselves and their families — who are without friends to support them— and who have no acknowledged claim on any public charity.

The business of the Society is conducted by a Committee of twelve, who are annually chosen, and who meet once a week. It is an established rule that previously to granting any supply, a sub-committee of two, on which all the members of the general committee, are placed in weekly rotation, visit the applicants personally, to inquire into their situation, assist them in the mean time if proper objects, and give in their report at the next meeting of the Committee, when it is determined who shall be put on the list for weekly supply, and what shall be their allowance. To prevent abuse or confusion each of the twelve members of the Committee has particular bounds assigned to him, within which he must personally visit the Society’s pensioners at least once a week; give them their pittance; and make such inquiry into their condition, as shall enable the Committee to judge at the subsequent meeting whether the charity should be continued or withdrawn.

The funds arise from small quarterly payments by the members — from private Donations by the affluent and generous — from occasional Legacies; — and from public Collections.

Contributors wishing to be satisfied as to the application of their money, may have full information by calling at the Society-Hall, Warriston’s Close — where regular accounts of all transactions are kept; and where the books are always open for inspection.

From the commencement of the Society to November 1800, being a period of fifteen years and about three months, they have distributed £3460 : 1 : 5 ½ among 7234 families, consisting of 16, 679 persons. And during the last twelve months, they have distributed £319 : 19 : 6 among 719 families consisting of 1789 persons, many of whom, it is to be presumed have been prevented from experiencing all the wretchedness inseparable from united penury and sickness.

Endnotes

1 By moral suasion is here meant not that king of reasoning which one graceless man may address to the understanding of another : but those persuasive to holiness which the Spirit of God in his word addresses to his grace in the heart. These faith applies and improves.