Cyrus Augustus Bartol (1813-1900) graduated from Harvard divinity school in 1835. He was a co-pastor with Charles Lowell at the West Church in Boston in 1837 and became the sole pastor of that church in 1861.

Relation of the Medical Profession to the Ministry:

A

DISCOURSE

PREACHED IN THE WEST CHURCH,

ON OCCASION OF THE DEATH OF

DR. GEORGE C. SHATTUCK.

BY C. A. BARTOL.

DISCOURSE.

Luke IX. 2: “AND HE SENT THEM TO PREACH THE KINGDOM OF GOD, AND TO HEAL THE SICK.”

Such was the commission which the great Physician of the human body and soul gave to his twelve disciples, when he clothed them with their office of carrying on his work in the world. In prophetic metaphor, the older revelation, too, had symbolized this very likeness of the mortal frame to the immortal spirit in their common exposure to disease, when it inquired if there were no balm in Gilead, and no physician there, to recover the health of the daughter of God’s people. Nay, the pagan religion itself foreshadowed the same thing from the remotest point and faintest beginning of its mythology, owning the healing art for a sacred function. The first that practiced it, to the heathen mind was a god and the child of a god; his immediate descendants, at the same time physicians and priests, lived in the temple, and allowed none to be initiated into the secrets of their knowledge without a solemn oath; while the most famous of the Greek physicians, who founded a school and was the earliest to raise medicine to the dignity of a science, was reputed to stand in the line of the same divine descent. You know, moreover, how intimately medicine and religion have been connected by the rudest savage tribes of our own day, as well as by the most civilized races of antiquity. But, to indicate for the pulpit my theme to-day of the medical profession in its relation to the ministry,—which you will allow me to treat in the plainest and most familiar manner,—it is enough to know, that a being before whom all the deities of classic story grow pale and fade away, in his own life and in his charge to his apostles, associated the ills of the flesh with those of the mind for the merciful remedies of his gospel.

There is something very touching in his selecting, for the particular proof of his own heavenly authority, this gracious work of relief and cure to the suffering human frame; restoring from fever and palsy and epilepsy and insanity, from blindness, deafness, dumbness, death. Ah! A cordial truth did his beneficent deeds express, that he came to be for ever the friend of the human body as well as soul, redeeming them both from anguish and corruption, from the sin that runs over into the dying part, and the sickness that penetrates to the undying: for he saw, as a superficial philosophy does not, the companionship between these two natures, so intimate no thought can divide and bound their territories, and so he took the whole man for his love and tenderness; and when the age of outward miracles ceased, and the Christian believer, as such, could no longer wondrously bring back lost health to the sick man, they who religiously devoted themselves to the study and exercise of the art of healing, in worship of the Divinity that made them, and in love of their fellow-creatures, in a business essentially partaking as much as any other of piety and humanity, in some sense in this respect succeeded to the apostles and to the great Lord and Master of us all.

One of the most interesting aspects of this general statement is the friendly relation that should subsist between the professors of medicine and the ministry. Surely they should be friends. Jesus Christ has formed the bond of their amity. He is in his life their common parent. They meet in his spirit. They trace back all that is benign and holy in their several offices and highest purposes to his temper and his acts. Jealousy between them is nothing less than an affront to him who, through all Galilee, taught in the synagogues, and healed the diseases of the people; and any mutual discord, from whatever cause arising, is a quarrel in the very body of the Son of God, and as though those messengers of his, when they went out through all Judea, bearing in one hand soundness for the flesh, and in the other comfort and salvation for the heart of man, had fallen out by the way. Distrust, alienation, divorce, between these professions, so long wedded, and ever in the daily round following in each other’s track, would indeed be not according to history, or according to Christianity, or according to the best hopes and auguries of the future welfare, private or public, of mankind. Therefore let us rejoice in the wide and substantial harmony that has ever prevailed in these two classes. The minister who refers to this topic, truly should not only rejoice, but give thanks, because of a peculiar generosity of the physician’s gratuitous service to his calling, a matter of less pecuniary than moral meaning. The minister, on his part, however, should at least pay with his gratitude his respect to the skill and science of the physician, honoring his vocation, and not lightly giving, as I see it said he sometimes does, the most precious, though commonly accounted the cheapest, thing a man can give, his name and recommendation to every presumption of ignorance and charlatan’s elixir, by whose author or vender he may be entreated. It is not the less but the more necessary to say this, because, in these times of the broader diffusion of light and a growing individual independence, the once marked enclosures and high fences of all the professions are somewhat invaded; men without title or preparation choosing to argue their own case, to hold forth their own revelations, and be their own doctors. With the awakening of thought and the spread of knowledge has come the ascertainment of our ignorance; no claims, private or professional, pass as they once did; and no occupation can stand any more on the ground of mere caste, of a strange tongue or a black letter, but only on the actual benefit it can yield to human beings, in mind, body, or estate.

Yet, in this shock to confidence and loss of reverence, accruing on the universal assertion of intellectual freedom, on the reign, too, of empiric observation, and the custom here in all things of our proverbial and characteristic American haste, there is danger that men will desert the truly wise, who have patiently and expensively qualified themselves for their instruction, defence, or restoration, and foolishly rely on their own imprudence, or the shallow boasts of those who have more at heart their own gain and interest, than any benefit to their kind. To this particular disadvantage, probably no one of the professions is so grossly exposed as the medical. For, while the severe preparation required for the law may reduce the number there of mere pretenders, and while the facts and themes of religion are for the most part matters of sober, scholarly investigation,—vulgar criticism, popular and rudely practical doubt, roused in part very possibly by many contrariant doctrines, seems to have fixed on the medical profession for its especial prey or chosen quarry to pursue; so that we ought not to be surprised were its members sometimes worried and vexed in this chase of hungry questioning and skepticism, sharpened by the lively concern everybody has in an affair so near to him as his own health, especially if this running after them be shared in or cheered on by any whose social position, reputation for learning, or personal hold on the affections of others, invests them with power to hinder or further any sentiment or cause.

It should, however, be some antidote to any irritation hence, that every one of the professions, in this curious and prying age, in some way, coarser or more refined, partakes in this trial of secret insinuations or open assaults. In the wisdom of God, no less than in the folly of man, it may be best for them that they should; for the miserable jeers that charge the lawyer with cunning and selfish appropriations of the sum in dispute, the minister as a dumb dog or covert infidel, and the doctor as at work to physic his patient into the grave, may but combine with candid or subtle investigations of the basis of each several vocation to impart a more finished quality, a nobler and disinterested stamp, to every worthy member of them all. Nay, the doubtful and deliberative tone thus infused into the habit of their minds, leading them to consider well before they act or speak, to indulge or enlighten all honest unbelief in others, and to lay aside whatever might be arrogant or overweening in themselves, will, in their simple modesty, and frank confession of how little as well as how much they know, assuming no oracular airs, but, for the ancient look of mysterious consequence or magical power, putting the benign aspect of depending on true science and a higher strength to secure a humane end, make them, with more accomplished control of their art, greater benefactors to their kind. Accordingly, I believe that justice was never more sure, or health safer, or morality and religion better cared for, than in their modern hands. You will not hint a worldly motive for this declaration. The man who basely attacks his own profession, and rends the cloth he wears, is as likely to have a worldly or ambitious aim, as he that respects his guild or calling; for well said old Samuel Johnson, that he who rails at established authority in any thing shall never want an audience; and an audience is what some seem most of all to crave! But, at whatever former period any of the professions may have been exalted in a more awful or formal respect, it may be doubted whether there was ever more earnestness or vitality, than may not seldom now be seen, in their exercise of every one of them.

The provinces of the minister and the physician, which I am now particularly considering, lie so near to each other, that there doubtless is in their relations a peculiar delicacy. They must be in fellowship, or else in some degree of envy, if not collision; for wholly separate they cannot be, nor should be. Indeed, both the human mind and body are, in their disordered states, so brought under the inspection alike of the messengers of health and of salvation, or spiritual health; the affections of the inner and outer part of human nature so run into, and are often well-nigh confounded with, one another; temperament is so close to temper, habit of body so linked with habit of mind, phlegm is such a name for sloth, and a sanguine or nervous frame such a neighbor to heat and irritability; there is so much gloom or brightness in the digestion; so much kindness in the circulations of the heart, or wrath in the flow of the bile; the vapors that rise or the beams that shine in one region of our marvelous soul or structure so soon overspread the other; a permanently morbid mood of mind, as one has said, so invariably indicates physical disorder; in fine, the soul owes so much to the body, as its organ, dwelling, school, and means of discipline, and the body so much to the soul in every good disposition and holier person; and virtue or vice, soundness or disease, wherever existing, seems so to take them both for a common abode; religion itself is sometimes such a medicine, and medicine such a succor and aid to the conscience; the roots and springs of health or sickness are so much in the moral condition, and make us think so often of—-

“the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,”—

that they who have attempted to divine in its morbid conditions this wondrous double-empire into their distinct rules may occasionally find themselves unwittingly assuming each other’s prerogatives, and trespassing or treading a little on each other’s grounds. Then, as the minister may know very little of medicine, and the physician as little of the springs of the moral life; as one may, in his meditations, have neglected the order of physical facts, and the other, in the ken scent of his observations, been drawn away from contemplating spiritual and invisible realities or principles,—they may interfere with each other, and do each some harm to the incarnate yet spiritual creature let down from Almighty Power into their associated charge. Therefore, it no doubt is best each should in general, as far as many be, occupy his own, avoiding the debatable land.

Yet, what singular opportunities are at times offered to the physician of giving spiritual counsel, peradventure all the more all the more potently because it is not precisely his technical place! How not unfrequently he has availed himself, as in duty bound, of openings for moral influence! Indeed, shall I say, it curiously illustrates the state of the case, that I have known the same worthy physician, who had complained of ministers looking after the bodies of his patients, to feel under the obligation of himself looking after and ministering to their souls! It were, in fact, but ungrateful for me to lose the memory, or omit here the mention, of my own sympathetic meetings, from time to time, with physicians on either side the bed, over the same suffering and the same death. Truly, for one, I am free to confess a sincere and unaffected pleasure, looking not with an evil eye, but with unalloyed admiration, whenever a word has been so fitly spoken, the kingdom of God preached, and the sick healed, as of old, by the same person! On the other hand, if a clergyman, not dealing in panaceas, or endorsing nostrums, or presuming to stand umpire between rival systems of medicine, should state or illustrate any of those great laws of nature that are over us, and in us, and through us all, on which human sanity hangs, and the transgression of a single one of which is sin, the generous and sensible physician, who is really laboring for the sake of God and man, will welcome the good service of his brother, as much as the farmer would the friendly hand, that, from its own concluded avocation, should come over to mow in his field or thresh on his floor. Let there be on either side no selfishness, no officiousness, no needless volunteering; but an inclination each one to do his own stint, lending help beyond only at the divine command in case of necessity; and, though they be borderers, they will, without strife or foray, live in peace.

But my purpose is not so much to adjust the terms of intercourse or mode of personal bearing between the two professions, as, being moved by the decease of an ornament of one and a friend of the other, to pay a warm and honest tribute of my regard to that to which I do not belong. The desk, whose incumbents everywhere are so indebted to that profession, may well offer, more frequently than it has done, such a tribute. At least, I shall not fail of it now according to the poor measure of my ability, partly as a token of regard for one who loved his own profession and mine both so well, and who would value honor done to his vocation, so long and nobly by him discharged and adorned, more than were it done to himself. The physician has in stewardship under God this mortal body in all the ills it incurs, or to which it is heir. It is a great and holy and most responsible trust. It seems to me so grand and tender, that I will not seek any-wise to lessen, but let it, for the moment, fill the whole field of view, that we may learn to do it and its holders more justice. I will not speak now of theology, the princely science, or alone of religion, the paramount concern, though I shall be enjoining a duty truly religious, or of the soul, the only endearing essence,—but of the body, the body which every one of us brought in hither this morning, and must lay down yonder at life’s evening,—our companion for a short stage, a poor, feeble, weary, ailing thing, but all we have to work with in this world, and which therefore, by every pain, dislocation, or infirmity it is rescued from, by every fever it burns, or chill it shakes with, by every fit which convulses it, or consumption in which it pines, pathetically appeals to us to render due credit to them who keep this many[jointed, myriad-chorded instrument, harp of thousand strings, of so universal play and turn, the true history of whose derangements would be almost as various and tragic as that of the passions of the human mind of which it is the earthly organ, in tune and repair.

Yes, honor to those who have probed he hiding-places of its power, laid open its minute cells; traced the course of its flowing streams; caught every one of the trembling nerves by which it acts or feels, communicates or receives; discovered the causes of its throbbings and its tears; snatched it so often from its most fearful jeopardizes; warned it of its many foes; hovered over it in its most critical emergencies; searched out every one of its disturbed conditions, and labored untiringly to redeem it from them all; actually converted many of its troubles, once fatal, into tolerable and curable maladies; in their devoted friendship passed night after night, as well as the lie-long day, with it, and encountered the fiercest storms that ever blew, and travelled over the most broken ways ever traversed in its behalf, never deserting it while breath remained; and, while spending themselves in outward toils, have brooded over all the elements and phenomena of nature, its grosser brother, in their relation to its symptoms, with the profoundest and most persevering study, to detect and gather every kind of material and invent every tool that advancing human knowledge could fit to alleviate its anguish, free it from the occasions of its distress, check the tendencies to disease, remove the obstructions from the way of its living nature, and lengthen out its days for the increase of human happiness and the manifestation of all the faculties and attributes of the immortal mind. They deserve well of their kind. Let them have their meed of praise and renown! Let those who have experienced their favors, if paid yet priceless, bring it! Let the pulpit yield it,—and even my weak words, for their sincerity, pass for the present hour and spot, as one of its humble signs and expressions!

Physicians, so honorably placed as we have seen in the Christian faith, one of them being styled “Luke the beloved,” have, as we well know, a corresponding rank and sphere in society. And here gain we touch on their inevitable union with the ministry. Their function, like the pastoral, is one of the threads that pass through the entire system of human life. It is one of the great bonds of union among men. Appointed to re-unite the sundered or confirm the debilitated bonds of corporeal well-being, to rejoin the dissevered ligaments, close gaping wounds, and set in motion the suspended workings of the animal frame, they are, by the unlimited reach of their benevolent and indispensable offices, also a solder and cement in the edifice of the common-weal. They do much to cure the body politic, as well as the individual constitution. The rich and the poor, the citizen and the stranger, the high and the low, the virtuous and the vile, the physician must take care of them all; and he follows the example of his Great Master in so doing. Like the central iron rod, or the main supporting beam, or the stout traversing keel, with which all is connected and on which all is more or less suspended or built, is the operation of his so strong and busy hand. None has more disagreeable, and it may be thankless, tasks than he. Yet this must be his consolation, that none comes nearer to the human heart, as well as to that which covers that heart, than the good physician who is also a good man. His chaise passing round is the very emblem of a benignant errand; or waiting at the door, an earnest to the passer-by, that good is going on within. “Who, is your physician?” is a question asked perhaps as often as any other, and always asked by friends with lively interest; and “my physician” are words rarely pronounced without a glow of emotion, if not a gush of thanksgiving, accorded to but few earthly benefactors. For all endeavor, patience, and watching, so spoken they are beyond silver and gold a remuneration to that human heart of ours which craves indeed many things beneath the sun, but above all other things hungers and thirsts for a just respect and a holy love. They that visit and heal the sick, that bring the color back into the pallid cheek, that enliven again the heavy lack-luster eye, enable hand and foot and head to resume their wonted avocations in all effort and delight of body or mind, and thus put a new song into the mouth for restoring mercy, certainly do not miss large and perhaps unequalled measures of that consideration which, second to the favor and blessing of Almighty God, is rightfully dearest to the soul. Heaven grant to them both benedictions, the human and the divine, with the grace to fulfill both the commandments,—the first of supreme love with all the heart and strength to God, and the second, which is like to it, of loving one’s neighbor as one’s self. Such the wish and prayer which the voice of this place would breathe towards them, and breathe for them up into the sky! And might I say one word further, from my theme, it would be,—May the prophecy of their friendship with the ministry of religion reach as far forward as its tradition reaches back!

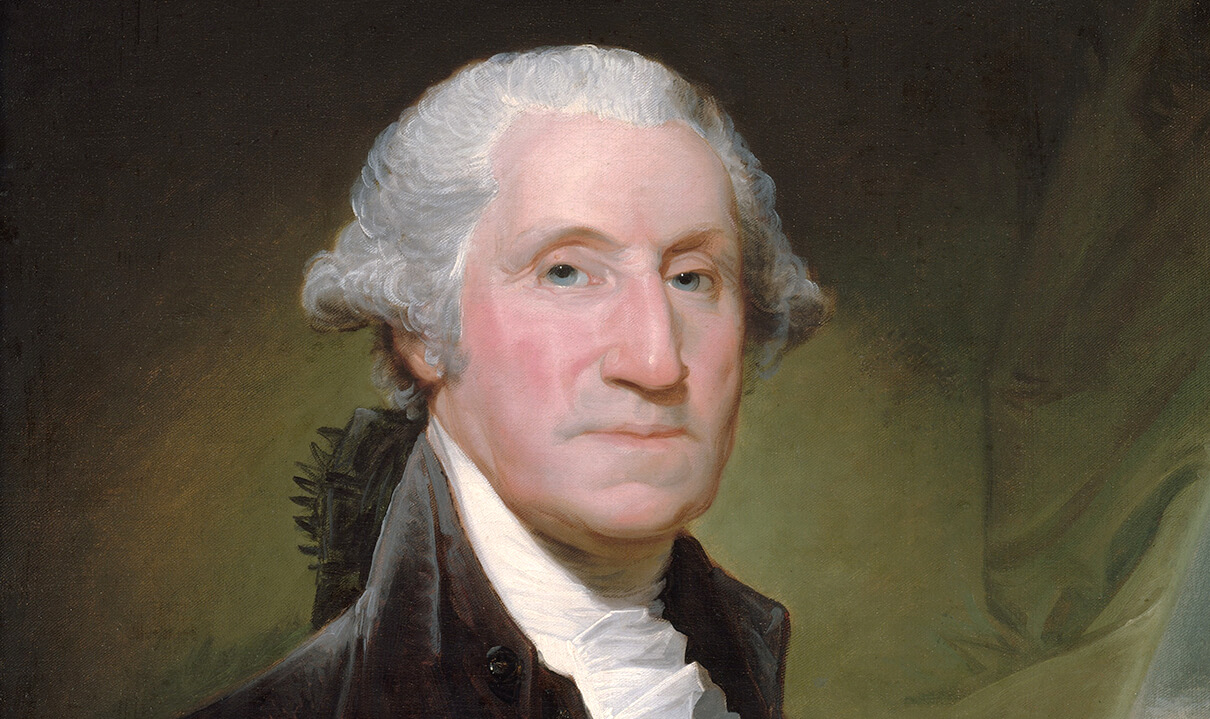

But the physician, who heals and under Providence lengthens out the lies of others, must himself sicken and die. While many, through his instrumentality, remain in the land of the living, he himself may have gone. Those he raised from prostration may visit his couch, and those he rescued from the grave weep grateful at his sepulcher. A vacancy here noticeable by you all makes needless any explanation of the motive of my present subject. A form, familiar for many years, and ever growing more venerable in our eyes, has disappeared. It was the form of one who might well suggest to me the text of this discourse; for no man ever respected more either his own profession or that of the ministry, or more closely associated them together in his mind; so that once, being examined under oath as to some record he might have made, he exclaimed that “by the grace of God the name of a minister was never entered with a charge on his books”! Yet he began his career, as perhaps it is best every young man should, having nothing in particular to trust to but his own talent and fidelity, with what I have heard him in his own phrase style “the healthy stimulus of prospective want;” and, waiting quietly for his first patients, attending slowly to case after case, he laid silently, stone by stone, the foundation of his fame. Every truly noble building rests on just such a basis of deep and secret diligence; and as a great merchant once said that the making of his first thousand dollars cost him more perplexity than all the rest of his immense fortune, so is it with the first achievement, by manifest, undeniable, and unmistakable power, of all professional success. The towering reputation far seen over the land, the wide-spread practice opening through a thousand portals, reposed simply and solidly on the genuine qualities which both assured skilful handling to the sick, and bore off prize after prize in the early competitions of the literary medical essay.

But our friend did more than eminently exemplify the essential traits of a wise and able practitioner. Though he has said to me he was a physician, and nothing but a physician,—while it is utterly superfluous for me to bring the fact of his professional superiority to your notice,—he was consulted on other matters beside the hazards and extremities of mortal life. Extraordinarily distinguished for insight into the soul as well as body, joining, in fact, the physical and the spiritual, that are brought into such juxtaposition in our text; reading character as he did health or disease; leaping through obstructions to his point, with an electric spark of genius that was in him; clothing his conclusions sometimes with a poetic color, and sometimes with the garb of a quaint phraseology; employing now a pithy proverb, and now a cautious and tender circumlocution, to utter what could scarce have been otherwise conveyed, in a method of conversation, which, in its straight lines or through all its windings, I never found otherwise than very instructive,—an intuitive sagacity and perfect originality marked all his sayings and doings. He could never be confounded with any other man. Borrowing neither ideas nor expressions, he was always himself. Yet there was nothing cynical or recluse or egotistical about him. I never heard him boast himself or despise another. He had a large and warm heart, with room in it for many persons and all humanity. Though he was so peculiar, much of his heart was the common heart, as the most marked and lofty mountains have in them most of the common earth. While not a few are absorbed in some single relation, he observed and acted well in the multitude of his relations to his fellow-men. He was remarkable for this broad look and observance of all the interests, material or moral, mechanical or spiritual, of the world, and was equally at home in a question of finance or an enterprise for religion; actually, in his early life and growing thrift, giving a large part of his property for the building of a church. He had, moreover, this precious singularity, that he never seemed to belong to any one class or little social circle, but to stand well and beneficently related to all. Often have I had occasion to perceive, not only his large and cordial, but very various and wide, hospitality. He fulfilled, as nearly as I remember to have seen it, that remarkable, difficult, and apparently almost uncomprehended precept of our Saviour, in which he tells, when we make a feast, not to call to it our friends and rich neighbors, but the poor, the maimed, the lame, the blind; and probably no man in this city could die, who would be remembered by a greater number of those in their necessity touched by his timely beneficence; for he seemed ever to discern the season, as well as to feel the inclination, to do good; his relief of another was less a tax or duty than a self-gratification; while he never forgot a favor he had received, he never allowed any one to feel a load from the favor he conferred. He did not wait to be asked. He did not yield to all solicitations. He preferred generally to give in his own way and of his own motion; and to no one did good deeds offer and suggest themselves more abundantly or opportunely. Before my personal acquaintance began, the first thing I knew of him was his attendance upon a sick fellow-student in Cambridge, coming often, yet refusing to receive any fee. And the next thing I knew of him was his receiving into his house, and then, like the good Samaritan with his message to the host of the inn, commending to a distant professional brother, another friend and fellow-student. It might not please him or those nearest to him, if I should attempt even partially to enumerate his bounties, so ample, to various institutions of learning, for their libraries or chairs of instruction, which in some instances may have come to your hearing; but I have reason to think that his kindness much more frequently flowed in private channels, beheld only by the recipients and the All-seeing.

Being such a hearty and unostentatious philanthropist, it is perhaps unnecessary to say, in addition, that he was a real Christian. But he belonged to no one sect or denomination of Christians. Referring all to God, taking the highest view of the divine dignity of Jesus Christ, hoping to be accepted, saved, reconciled to the Father through the mediation of the Son, he extended his sympathy and hand of fellowship to all the faithful preachers of the gospel. He was truly catholic. You will excuse me, but there must be put into any conscientious report of him, what will indeed appear as but one practical exposition of the general truth of this discourse, his repeated mention of his especial regard for ministers,—“ministers,” he added with emphasis, “not of one name, but of all;” and his deference to the ministerial office is a quality in him, certainly in these days, standing out with some prominence. Indeed, the inclination of his respect might have been embarrassing but for he fraternal and authentic good-will from which it came. His respect ever somewhat veiled his heart, protecting an exquisite sensibility, which all might not notice, and hindered him from professing the entire warmth of personal affection he felt. But a reverence for the Most High was in him wholly distinct from all other principles. His will towards men was strong. But he seemed to have no will towards God. His will vanished before the Supreme; and he would have none beside. As a physician, he looked not to his medicines alone, but to God, for success, and prayed before he prescribed.

So it was with him, with ever-increasing interest, to the last. “Pray with me” was commonly his first salutation as I entered his sick chamber. “I want your prayers: they are a great comfort and consolation.” “Pray not for my recovery.” “I am going to God.” “I wish in your prayer to go as a sinner.” “I humbly thank you” was in the pressure of his hand, as much as in the articulate motion of his lips, when the express act of devotion was over. “Next to my God, I want to be near to my minister,” referring, of course, not to the individual, but, as was his wont, the office. And, at the last, having spoken his love to those most closely related to him, just before he went, “Time, Eternity, Eternity, Eternity,” were his expiring words; knowing, as he retained possession of his mind, that he was just stepping over that mysterious causeway, hid from mortal eyes, the sight of which no fleshly vision could bear, which separates one from the other.

I need not say, for the information of any in this society, that, being thus devout, he was a willing and open-handed supporter of religious institutions. To the utmost extent of his strength and opportunity, he was a constant, as he was a happy, worshipper in this house. He was an humble, penitent, affectionate confessor of his Lord at this communion-table, from which he had been long restrained by diffidence; but, in the last year of his life, was ready joyfully to bear witness, through the emblems of the broken body and flowing blood of the Saviour, that the confidence which, whether coming or staying away, we cannot feel in ourselves, we may feel in him and in God. The square and fountain in front of this church; the marble baptismal font before this altar, much of whose expense it was one of his dying bequests should be paid by his kindred survivors, at the same time declaring his delight in its beauty, thus associating it for ever with his departure; the repair and enlargement of the room for the Sunday-school, to which he chiefly contributed, affirming to me more than once how important he considered the religious instruction of the youth among us; the libraries for the school and the parish, which he increased with special donations,—are but examples selected from the numerous fruits and demonstrations of his Christian and reverential charity. Ah! But for faith and encouragement to emulation of such good deeds, it were a sorry day for any religious body when such a benefactor dies!

In thus reporting, as truly and exactly as I am able, the positive excellencies of our friend, I intend not, as is the custom in some eulogies, to imply that they were all; when the value of any praise of mortals lies in the definite truth that leaves room for fair exceptions, while the fulsome commendation that does not discriminate is merely worthless, signifying nothing. It would be a poor compliment to one, who perhaps was never guilty of an insincerity in his life, to intimate that he had no failings, or to present any panegyric of perfection for his character; to declare that this good man and true-hearted Christian had but one immaculate side, or moral features only of absolute beauty, which would so contradict his own word and consciousness. And were I to say that his fine natural ardor went not to the least excess; that his energetic purpose in no instance was imperious; that, bent upon action, and on speedily executing his good plans, he never became impatient of debate, or did any injustice to others’ thoughts, or exercised mastery over others’ designs; or that, prospered greatly as he was in his fortunes, it was never requisite for him to struggle against the world’s getting undue possession of his mind; that he was such a paragon, he never spoke harshly or acted hastily; in short, that no defects qualified and mingled with the rare and unsurpassed nobilities of his soul; and that even unawares he favored nothing wrong, nor opposed and put down any thing right,—I should insult his honesty, and belie my own conscience, and might do despite to that spirit of grace and truth, which, above the highest human attainments, still holds the unreached standard of moral goodness and infinite glory. But, if he could set his face as flint, oh! He could pour out his heart like water; the rock of rugged strength welling with currents copious and pure, for he was a pure-hearted man; and never was a gentler or more pathetic soul, a breast quicker to throb, or an eye more moist, at any grand or affecting spectacle or tale; if he was not caressing, neither was he self-indulgent; and if his passion ever overstepped the bounds of equity, he was prompt to feel remorse, humility, and grief, as more than once I have myself had occasion to note; while his character was continually softening, improving, ripening, as he went on,—ripe, fully ripe, indeed, at last!

But the question, in regard to any among mortals, is not whether he is faultless, none that breathe or ever did breathe being such; but, after the faults are subtracted, the question is, what mass, what weight, what height of worth, is left behind. Some seem to have neither grievous faults nor shining virtues; and a man may be apparently well-nigh blameless, without being very good, as a pure ore of iron or copper is not so precious as the mineral gold, though with earth and stone intermixed. My friend always seemed to me to be the mineral gold. Nor do I know where, in any individual, to look for a larger amount of the sterling treasure. Ah, while I speak of him, I can hardly imagine him away! A vision, he rises in my path, invites my gaze, greets me at the door, sits there in the sanctuary! The intensity of this abiding presence that will not down, of this reality that will not go, is the measure of force that has been in a man. And he surely was one of the powers among us that cannot cease even here below.

It is not the habit of this place to celebrate the merits of any human being. Nor might I have done it now, save to unfold with livelier interest, through a solemn dispensation of Providence, a subject of universal concern. The characters of all human beings sink before that Holy Majesty which fills this place, and which we here assemble to adore. But God is glorified not only by direct praise and ascending prayer. He is glorified, too, in his faithful servants, imperfect men though they be. All the beauty and splendor of the earth and heavens cannot compass so fair or sublime a pitch of his glory as is displayed in the loyal and loving souls of his children. We do not honor him by hiding out of sight, or passing over in silence, aught just or worthy in his intelligent creatures; but every light of virtue, taken from under the bushel of privacy to shine out of the candlestick of a true confession before men, illuminates also, to their view, the spotless attributes of the Creator. To the Creator, as its source, we ascribe all that is worthy and good. We thank him for the fruit of the earth. We thank him for the brightness of the sun. We thank him for the better beams of knowledge, and the nobler springing from every germ and disclosure of his sacred truth. We thank him, above all, for that manifestation of his wisdom and love which we discern in his obedient offspring, and which was incarnate in his beloved Son.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!