Joseph Reed (1741-1785) was born in New Jersey; graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) in 1757; and practiced law in New Jersey and Philadelphia. He served in the American army as aide-de-camp and secretary to George Washington (1775) and as Adjutant General (1776-1777). Reed was a member of the Continental Congress in 1778 where he signed the Articles of Confederation. He served as President (Governor) of Pennsylvania from 1778-1781.

Joseph Reed issued the following proclamation on November 29, 1779 as president of Pennsylvania declaring December 9, 1779 a day of Thanksgiving. The text and image of this proclamation is taken from The Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser published on November 30, 1779.

JOSEPH REED, Esquire,

President, and the Supreme Executive Council of the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

A PROCLAMATION.

WHEREAS the Honorable the Congress of the United States of America, by their resolve of the twentieth day of October last, did recommend in the following words, to wit:

“WHEREAS it becomes us humbly to approach the throne of Almighty God, with gratitude and praise, for the wonders which His goodness has wrought in conducting our forefathers to this Western world; for His protection to them and to their prosperity, amid difficulties and dangers; for raising us their children from deep distress, to be numbered among the nations of the earth; and for arming the hands of just and mighty Princes in our deliverance; and especially for that He hath been pleased to grant us the enjoyment of health, and so to order the revolving seasons, that the earth hath produced her increase in abundance, blessing the labors of the husbandman and spreading plenty thro’ the land; that He hath prospered our arms and those of our ally, been a shield to our troops in the hour of danger, pointed their swords to victory and led them in triumph over the bulwarks of the foe that He hath gone with those who went out into the wilderness against the savage tribes; that He hath stayed the hand of the spoiler, and turned back His meditated destruction, that He hath prospered our commerce and given success to those who fought the enemy on the face of the deep; and above all, that He hath diffused the glorious light of the Gospel, whereby, through the merits of our gracious Redeemer, we may become the heirs of His eternal glory. Therefore,

“RESOLVED, That it be recommended to the several States to appoint THURSDAY the ninth of December next, to be a day of public and solemn THANKSGIVING to Almighty God, for His mercies, and of PRAYER, for the continuance of His favor and protection to these United States; to beseech Him that He would be graciously pleased to influence our public councils, and bless them with wisdom from on high, with unanimity, firmness and success, that He would go forth with our hosts and crown our arms with victory; that He would grant to His Church the plentiful effusions of Divine grace, and pour out His Holy Spirit on all Ministers of the Gospel; that He would bless and prosper the means of education, and spread the light of Christian knowledge through the remotest corners of the earth; that He would smile upon the labors of His people and cause the earth to bring forth her fruits in abundance, that we may with gratitude and gladness enjoy them; that He would take into His Holy protection our illustrious Ally, give him victory over his enemies, and render him signally great, as the father of his people, and the protector of the rights of mankind; that He would graciously be pleased to turn the hearts of our enemies, and to dispense the blessings of peace to contending nations; that He would in mercy look down upon us, pardon all our sins, and receive us into His favor; and, finally, that He would establish the Independence of these United States upon the basis of religion and virtue, and support and protect them in the enjoyment of peace, liberty and safety.”

WHEREFORE, as well in respect of the said recommendation of Congress, as the plain dictates of duty, to acknowledge the favor and goodness of Providence, and implore Its further protection: We Do hereby earnestly recommend to the good people of Pennsylvania, to set apart THURSDAY, the ninth day of December next, for the pious purposes expressed in the said resolve; and that they abstain from all labor on that day.

GIVEN under the Hand of His Excellency Joseph Reed, Esq; President, and the Seal of the State, at Philadelphia, this twenty-ninth day of November, in the year of our Lord One thousand seven hundred and seventy nine, and in the Fourth year of the Independence of the United States of America.

JOSEPH REED, President.

Attest, T. MATLACK, Secretary.

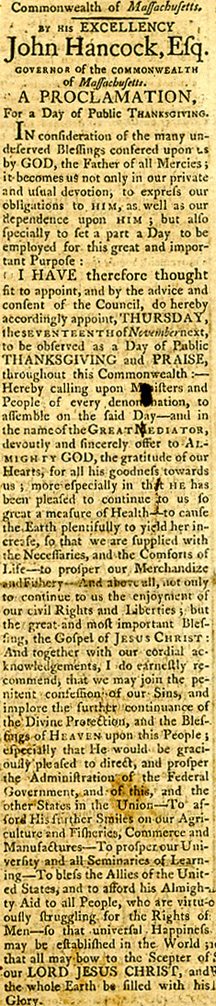

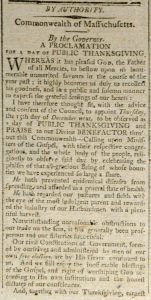

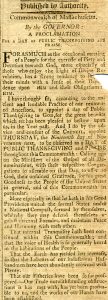

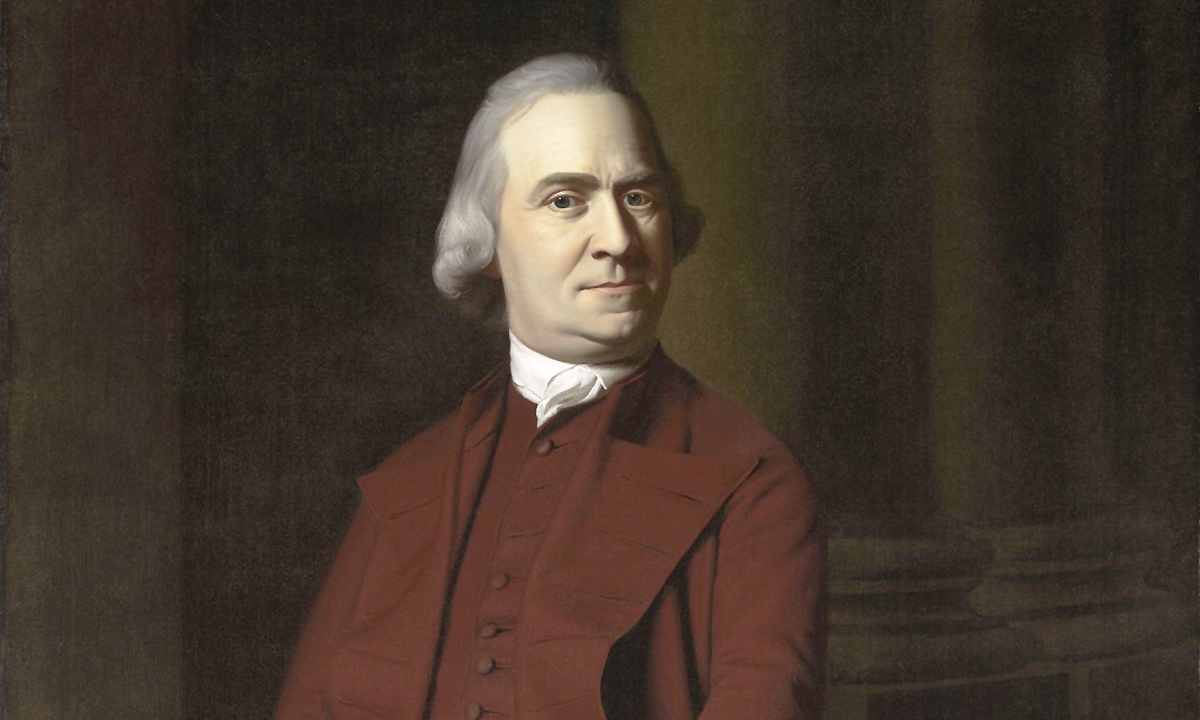

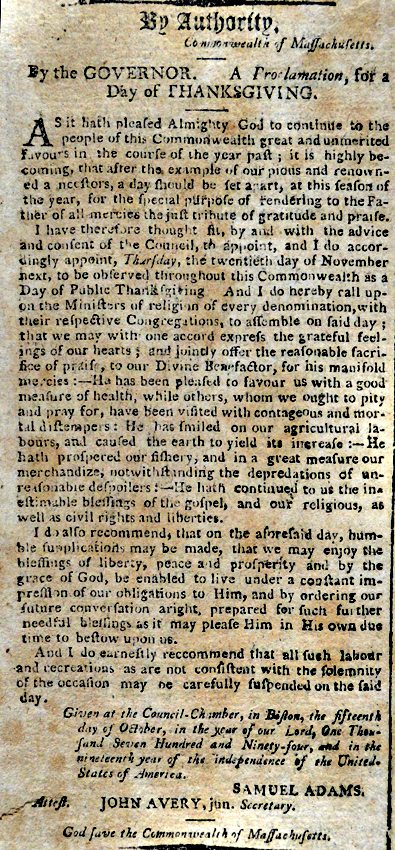

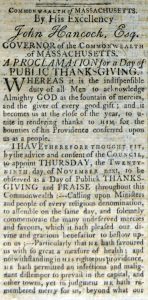

WHEREAS it is the indispensable duty of all Men to acknowledge Almighty GOD as the fountain of mercies, and the giver of every good gift; and it becomes us at the close of the year, to unite in rendering thanks to Him for the bounties of his Providence conferred upon us as a people.

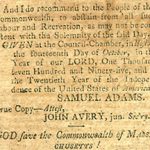

WHEREAS it is the indispensable duty of all Men to acknowledge Almighty GOD as the fountain of mercies, and the giver of every good gift; and it becomes us at the close of the year, to unite in rendering thanks to Him for the bounties of his Providence conferred upon us as a people. And, together with our sincere and pious acknowledgments, I do earnestly recommend, the penitent confession of our sins; amendment of our hearts and lives, and humble supplication to GOD, for His further aid, protection and blessing:—That He would especially be pleased to endue the administrators of the federal constitution, and of this, and the other States in the Union, with sound wisdom and understanding; the fear of GOD, and love of their country, and a single aim to preserve and promote the liberty, prosperity and happiness of the people: And that He would grant to all, a spirit of truth, and discernment; a due regard to every wise administration, and to the importance of internal peace and Union:—To afford His further smiles on our agriculture, fisheries, commerce, and all the labor of our hands;—To guide and direct the University, and all schools and seminaries of learning, so that our children and youth, by a wholesome education, may be deeply impressed with the principles of true religion, and solid virtue.—That He would be pleased to afford His almighty aid to all people, and more especially the French Nation, who are virtuously struggling for their just and equal rights. And finally, that He would be pleased to overrule the commotions and confusions that are in the earth, to the speedy downfall of tyranny and oppression, so that the kingdom of our LORD and SAVIOR JESUS CHRIST may be established in Peace and Righteousness, among all the Nations of the Earth.

And, together with our sincere and pious acknowledgments, I do earnestly recommend, the penitent confession of our sins; amendment of our hearts and lives, and humble supplication to GOD, for His further aid, protection and blessing:—That He would especially be pleased to endue the administrators of the federal constitution, and of this, and the other States in the Union, with sound wisdom and understanding; the fear of GOD, and love of their country, and a single aim to preserve and promote the liberty, prosperity and happiness of the people: And that He would grant to all, a spirit of truth, and discernment; a due regard to every wise administration, and to the importance of internal peace and Union:—To afford His further smiles on our agriculture, fisheries, commerce, and all the labor of our hands;—To guide and direct the University, and all schools and seminaries of learning, so that our children and youth, by a wholesome education, may be deeply impressed with the principles of true religion, and solid virtue.—That He would be pleased to afford His almighty aid to all people, and more especially the French Nation, who are virtuously struggling for their just and equal rights. And finally, that He would be pleased to overrule the commotions and confusions that are in the earth, to the speedy downfall of tyranny and oppression, so that the kingdom of our LORD and SAVIOR JESUS CHRIST may be established in Peace and Righteousness, among all the Nations of the Earth.