It is ironic that two prominent Founding Fathers who owned slaves (Thomas Jefferson and George Washington) were both early, albeit unsuccessful, pioneers in the movement to end slavery in their State and in the nation. Both Washington and Jefferson were raised in Virginia, a geographic part of the country in which slavery had been an entrenched cultural institution. In fact, at the time of the Founders, the morality of slavery had rarely been questioned; and in the 150 years following the introduction of slavery into Virginia by Dutch traders in 1619, there had been few voices raised in objection. That began to change in 1765, for as a consequence of America’s examination of her own relationship with Great Britain, there arose for the first time a serious contemplation of the propriety of African slavery in America. As Founding Father John Jay explained, this was the period in which America’s attitude towards slavery began to change:

Prior to the great Revolution, the great majority . . . of our people had been so long accustomed to the practice and convenience of having slaves that very few among them even doubted the propriety and rectitude of it. 1

As the Colonists increasingly recognized that they themselves were slaves of the British Empire, and were experiencing the discomforting effects of such power exercised over them, their commiseration with those enslaved in America began to grow. As one early legal authority explained:

The American Revolution. . . . was undertaken for a principle, was fought upon principle, and the success of their arms was deemed by the Colonists as the triumph of the principle. That principle was. . . . an ardent love of personal liberty, and hence, the very declaration of their political liberty announced as a self-evident truth that all men were created free and equal. 2

Notwithstanding this emerging change in attitude, the response across America on how to end slavery differed widely according to geographical regions. As Thomas Jefferson explained:

Where the disease [slavery] is most deeply seated, there it will be slowest in eradication. In the northern States, it was merely superficial and easily corrected. In the southern, it is incorporated with the whole system and requires time, patience, and perseverance in the curative process. 3

As a middle colony, Virginia experienced the stress from the divergent pull of both northern and southern beliefs meeting in conflict in that State. Several northern States were moving rapidly toward ending slavery, while the deepest southern States of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia largely refused even to consider such a possibility. 4Virginia contained strong proponents of both attitudes. While many Virginia leaders sought to end slavery in that State (George Mason, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, etc.), they found a very cool reception toward their ideas from many of their fellow citizens as well as from the State Legislature. As explained by a southern abolitionist, part of the reason for the unfriendly reception to their proposals proceeded from the fact that:

Virginia alone in 1790 contained 293,427 slaves, more than seven times as many as [Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey] combined. Her productions were almost exclusively the result of slave labor. . . . The problem was one of no easy solution, how this “great evil,” as it was then called, was to be removed with safety to the master and benefit to the slave. 5

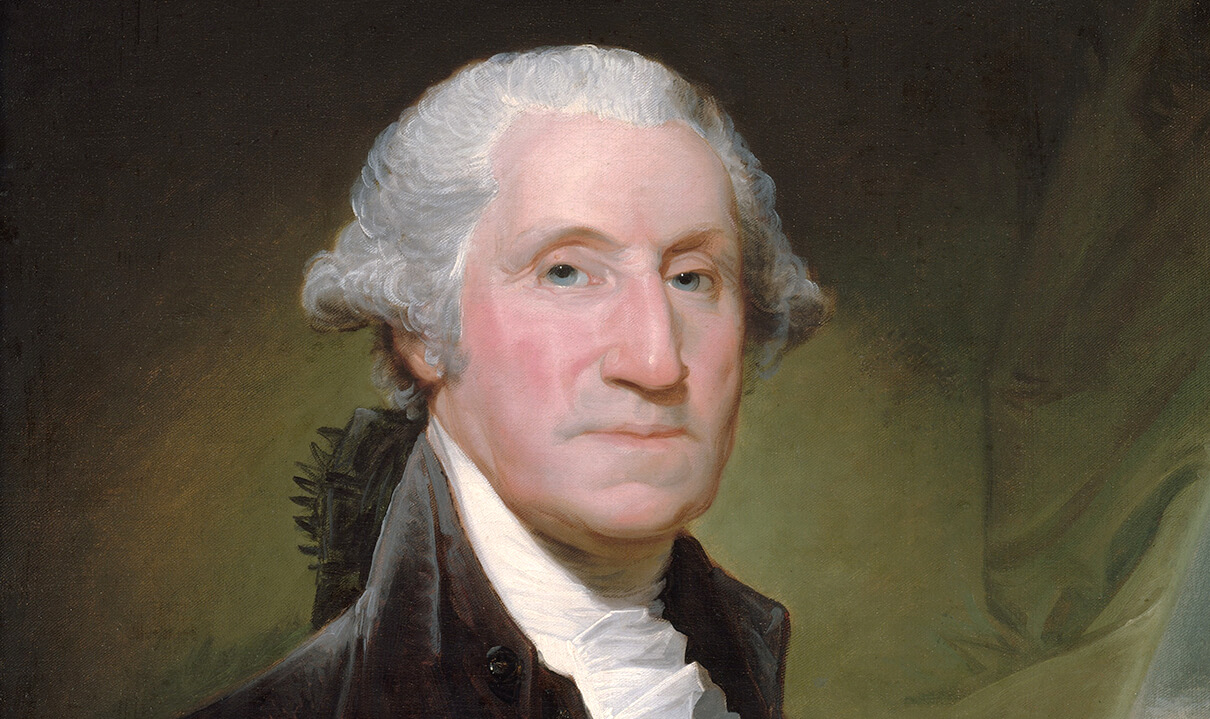

As Jefferson and Washington sought to liberalize the State’s slavery laws to make it easier to free slaves, the State Legislature went in exactly the opposite direction, passing laws making it more difficult to free slaves. (As one example, Washington was able to circumvent State laws by freeing his slaves in his will at his death in 1799; by the time of Jefferson’s death in 1826, State laws had so stiffened that it had become virtually impossible for Jefferson to use the same means.) What today have become the almost unknown views and forgotten efforts of both Washington and Jefferson to end slavery in their State and in the nation should be reviewed. Consider first the views of George Washington. Born in 1732, his life demonstrates how culturally entrenched slavery was in that day. Not only was Washington born into a world in which slavery was accepted, but he himself became a slave owner at the tender age of 11 when his father died, leaving him slaves as an inheritance. As other family members deceased, Washington inherited even more slaves. Growing up, then, from his earliest youth as a slave owner, it represented a radical change for Washington to try to overthrow the very system in which he had been raised. Washington astutely recognized that the same singular force would be either the great champion or the great obstacle to freeing Virginia’s slaves, and that force was the laws of his own State. Concerning the path Washington desired to see the State choose, he emphatically declared:

I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it [slavery]; but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by Legislative authority; and this, as far as my suffrage [vote and support] will go, shall never be wanting [lacking]. 6

As Washington had pledged, he did provide his support and leadership in efforts to end the slave trade. For example, on July 18, 1774, the committee which Washington chaired in his own Fairfax County passed the following act:

Resolved, that it is the opinion of this meeting that during our present difficulties and distress, no slaves ought to be imported into any of the British colonies on this continent; and we take this opportunity of declaring our most earnest wishes to see an entire stop for ever put to such a wicked, cruel, and unnatural trade. 7

Having developed this position, Washington maintained it throughout his life and reaffirmed it often. For example, when General Marquis de Lafayette decided to buy a plantation in French Guiana for the purpose of freeing its slaves and placing them on the estate as tenants, Washington wrote Lafayette:

Your late purchase of an estate in the colony of Cayenne, with a view of emancipating the slaves on it, is a generous and noble proof of your humanity. Would to God a like spirit would diffuse itself generally into the minds of the people of this country, but I despair of seeing it. Some petitions were presented to the [Virginia] Assembly at its last session for the abolition of slavery, but they could scarcely obtain a reading. 8

And to his nephew and private secretary, Lawrence Lewis, Washington wrote:

I wish from my soul that the legislature of this State could see the policy of a gradual abolition of slavery. 9

In addition to the slaves he inherited, Washington also bought some fifty slaves prior to the Revolution, although he apparently purchased none afterward, 10 for he had reached the decision that he would no longer participate in the slave trade, and would never again buy or sell a slave. As he explained:

I never mean . . . to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by which slavery in this country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees. 11

As the laws of Virginia did not permit him to emancipate his slaved (those laws will be reviewed later in this work), the only other means for him to dispose of the slaves he held was to sell them. And had Washington not become so opposed to selling slaves, he gladly would have used that means to end his ownership of all slaves. As he explained:

Were it not that I am principled against selling Negroes . . . I would not in twelve months from this date be possessed of one as a slave. 12

Interestingly, the personal circumstances faced by Washington provide decisive proof that his convictions were indeed genuine and not merely rhetorical. The quantity of slaves which he held was economically unprofitable for Mount Vernon †and caused a genuine hardship on the estate. As Washington explained:

It is demonstratively clear that on this Estate (Mount Vernon) I have more working Negroes by a full [half] than can be employed to any advantage in the farming system. 13

What, then, could Washington do to reduce his expenses and to increase profits? An obvious solution was to sell his “surplus” slaves. Washington could thereby readily accrue immediate and substantial income. As prize-winning historian James Truslow Adams correctly observed:

One good field hand was worth as much as a small city lot. By selling a single slave, Washington could have paid for two years all the taxes he so complained about. 14

Washington acknowledged the profit he could make by reducing the number of his slaves, declaring:

[H]alf the workers I keep on this estate would render me greater net profit than I now derive from the whole. 15

Yet, despite the vast economic benefits he could have reaped, Washington nevertheless adamantly refused to sell any slaves. As he explained:

To sell the overplus I cannot, because I am principled against this kind of traffic in the human species. To hire them out is almost as bad because they could not be disposed of in families to any advantage, and to disperse [break up] the families I have an aversion. 16

This stand by Washington was remarkable. In fact, refusing not only to sell slaves but also refusing to break up their families distinctly differentiates Washington from the culture around him and particularly from his State legislature. Virginia law, contrary to Washington’s personal policy, recognized neither slave marriages nor slave families. 17

Yet, not only did Washington refuse to sell slaves or to break up their families but he also felt a genuine responsibility to take care of the slaves he held until there was, according to his own words, a “plan adopted by which slavery in this country may be abolished.” One proof of his commitment to care for his slaves regardless of the cost to himself was his order that:

Negroes must be clothed and fed . . . whether anything is made or not. 18

Not only did George Washington commit himself to caring for his slaves and to seeking a legal remedy by which they might be freed in his State but he also took the leadership in doing so on the national level. In fact, the first federal racial civil rights law in America was passed on August 7, 1789, with the endorsing signature of President George Washington. That law, entitled “An Ordinance of the Territory of the United States Northwest of the River Ohio,” prohibited slavery in any new State that might seek to enter the Union. Consequently, slavery was prohibited in all the American territories held at the time; and it was because of this law, signed by President George Washington, that Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin all prohibited slavery. Despite the slow but steady progress made in many parts of the nation, especially in the North, the laws in Virginia were designed to discourage and prevent the emancipation of slaves. The loophole which finally allowed Washington to circumvent Virginia law was by emancipating his slaves on his death, which he did. Notice the following provisions from his will which embodied the two policies he had pursued during his life,the care and well-being of his slaves and their personal emancipation:

Upon the decease of my wife, it is my will and desire that all the slaves which I hold in my own right shall receive their freedom. -To emancipate them during her life would, though earnestly wished by me, be attended with such insuperable difficulties on account of their intermixture by marriages with the Dower [inherited] Negroes as to excite the most painful sensations, if not disagreeable consequences from the latter, while both descriptions are in the occupancy of the same proprietor; it not being in my power, under the tenure by which the Dower Negroes are held, to manumit [free] them. -And whereas among those who will receive freedom according to this devise, there may be some who from old age or bodily infirmities, and others who on account of their infancy, that will be unable to support themselves; it is my will and desire that all who come under the first and second description shall be comfortably clothed and fed by my heirs while they live; -and that such of the latter description as have no parents living, or if living are unable or unwilling to provide for them, shall be bound by the court until they shall arrive at the age of twenty five years; -and in cases where no record can be produced whereby their ages can be ascertained, the judgment of the court upon its own view of the subject, shall be adequate and final. -The Negroes thus bound are (by their masters or mistresses) to be taught to read and write and to be brought up to some useful occupation agreeably to the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia providing for the support of orphan and other poor children. -And I do hereby expressly forbid the sale or transportation out of the said Commonwealth of any slave I may die possessed of, under any pretense whatsoever. -And I do moreover most pointedly and most solemnly enjoin it upon my executors hereafter named, or the survivors of them, to see that this clause respecting slaves and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled at the epoch at which it is directed to take place without evasion, neglect or delay, after the crops which may then be on the ground are harvested, particularly as it respects the aged and infirm; -Seeing that a regular and permanent fund be established for their support so long as there are subjects requiring it, not trusting to the uncertain provision to be made by individuals. -And to my mulatto man, William (calling himself William Lee), I give immediate freedom; or if he should prefer it (on account of the accidents which have rendered him incapable of walking or of any active employment) to remain in the situation he now is, it shall be optional to him to do so: In either case, however, I allow him an annuity of thirty dollars during his natural life, which shall be independent of the victuals and clothes he has been accustomed to receive, if he chooses the last alternative; but in full, with his freedom, if he prefers the first; -and this I give him as a testimony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War. 19

Significantly, numerous incidents in George Washington’s life provide ample proof that he suffered from no racial bigotry. Those incidents include his approving a free black, Benjamin Banneker, as a surveyor to lay out the city of Washington, D. C., and his patronage of black poet Phillis Wheatley. In fact, after Phillis wrote a poem in 1775 praising General Washington, Washington made plans to publish the piece but then feared that the public would misunderstand his publication of a poem praising himself, believing it was a sign of his own vanity rather than as an intended tribute to Phillis. As Washington told her:

I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me in the elegant lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyric [lofty praise], the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical talents. In honor of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the poem had I not been apprehensive that, while I only meant to give the world this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public prints. If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favored by the muses and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. 20

Additional proof of Washington’s lack of personal bigotry is provided by numerous black authors. One, for example, was Edward Johnson, a former slave and an abolitionist who was an author of textbooks for school children, particularly for young African-American students following the Civil War. Johnson provided the following anecdote:

Washington [was] out walking one day in company with some distinguished gentlemen, and during the walk he met an old colored man, who very politely tipped his hat and spoke to the General. Washington, in turn, took off his hat to the colored man; on seeing this, one of the company, in a jesting manner, inquired of the General if he usually took off his hat to Negroes. Whereupon Washington replied: “Politeness is cheap, and I never allow any one to be more polite to me than I to him.”21

Other anecdotes were provided by William C. Nell, a former slave who became an ardent abolitionist. Nell wrote numerous works on black history and against slavery preceding the Civil War, and in one of those works, he provided the following anecdote of Washington and Primus Hall:

Primus Hall. -Throughout the Revolutionary war, he [Primus Hall] was the body servant of Col. Pickering, of Massachusetts. He [Hall] was free and communicative, and delighted to sit down with an interested listener and pour out those stores of absorbing and exciting anecdotes with which his memory was stored.

It well known that there was no officer in the whole American army whose friendship was dearer to Washington, and whose counsel was more esteemed by him, than that of the honest and patriotic Col. Pickering. He was on intimate terms with him, and unbosomed himself to him with as little reserve as, perhaps, to any confidant in the army. Whenever he was stationed within such a distance as to admit of it, he [Washington] passed many hours with the Colonel, consulting him upon anticipated measures and delighting in his reciprocated friendship.

Washington was, therefore, often brought into contact with the servant of Col. Pickering, the departed Primus. An opportunity was afforded to the Negro to note him [Washington] under circumstances very different from those in which he is usually brought before the public and which possess, therefore, a striking charm. I remember [one] anecdote from the mouth of Primus. . . . so peculiar as to be replete with interest. The authenticity of . . . may be fully relied upon. . . .

[T]he great General was engaged in earnest consultation with Col. Pickering in his tent until after the night had fairly set in. Head-quarters were at a considerable distance, and Washington signified his preference to staying with the Colonel over night, provided he had a spare blanket and straw.

“Oh, yes,” said Primus, who was appealed to; “plenty of straw and blankets-plenty.” Upon this assurance, Washington continued his conference with the Colonel until it was time to retire to rest. Two humble beds were spread, side by side, in the tent, and the officers laid themselves down, while Primus seemed to be busy with duties that required his attention before he himself could sleep. He worked, or appeared to work, until the breathing of the prostrate gentlemen satisfied him that they were sleeping; and then, seating himself on a box or stool, he leaned his head on his hands to obtain such repose as so inconvenient a position would allow. In the middle of the night Washington awoke. He looked about and descried the Negro as he sat. He gazed at him awhile and then spoke.

“Primus!” said he, calling; “Primus!”

Primus started up and rubbed his eyes. “What, General?” said he.

Washington rose up in his bed. “Primus,” said he, “what did you mean by saying that you had blankets and straw enough? Here you have given up your blanket and straw to me that I may sleep comfortably while you are obliged to sit through the night.”

“It’s nothing, General,” said Primus. “It’s nothing. I’m well enough. Don’t trouble yourself about me, General, but go to sleep again. No matter about me. I sleep very good.”

“But it is matter-it is matter,” said Washington, earnestly. “I cannot do it, Primus. If either is to sit up, I will. But I think there is no need of either sitting up. The blanket is wide enough for two. Come and lie down here with me.”

“Oh, no, General!” said Primus, starting, and protesting against the proposition. “No; let me sit here. I’ll do very well on the stool.”

“I say, come and lie down here!” said Washington, authoritatively. “There is room for both, and I insist upon it!”

He threw open the blanket as he spoke and moved to one side of the straw. Primus professes to have been exceedingly shocked at the idea of lying under the same covering with the commander-in-chief, but his tone was so resolute and determined that he could not hesitate. He prepared himself, therefore, and laid himself down by Washington; and on the same straw, and under the same blanket, the General and the Negro servant slept until morning. 22

Nell also provided the following story entitled “A Tribute from the Emancipated, by Washington’s Freed Men” from the Alexandria, D.C. Gazette to illustrate the respect that Washington’s former slaves had for him:

Upon a recent visit to the tomb of Washington [at Mount Vernon], I was much gratified by the alterations and improvements around it. Eleven colored men were industriously employed in leveling the earth and turfing around the sepulcher. There was an earnest expression of feeling about them that induced me to inquire if they belonged to the respected lady of the mansion. They stated they were a few of the many slaves freed by George Washington, and they had offered their services upon this last melancholy occasion as the only return in their power to make to the remains of the man who had been more than a father to them; and they should continue their labors as long as anything should be pointed out for them to do. I was so interested in this conduct that I inquired their several names, and the following were given me: -Joseph Smith, Sambo Anderson, William Anderson his son, Berldey Clark, George Lear, Dick Jasper, Morris Jasper, Levi Richardson, Joe Richardson, Wm. Moss, Win. Hays, and Nancy Squander, cooking for the men. -Fairfax County, Va., Nov. 14, 1835. 23

Washington was truly one of the leaders in Virginia who sought to end slavery in that State (and the nation) and who worked to bring civil rights to all Americans, regardless of color. Jefferson, too, sought similar goals, but by living twenty-seven years longer than Washington, Jefferson faced additional hostile State laws which Washington had not. But before reviewing Jefferson’s words and actions regarding slavery, a brief review of the overall trend of the laws of Virginia on the subject are in order. In 1692, Virginia passed a law that placed an economic burden on any slave owner who released his slaves, thus discouraging owners from freeing their slaves. That law declared:

[N]o Negro or mulatto slave shall be set free, unless the emancipator pays for his transportation out of the country within six months. 24

(Subsequent laws imposed additional provisions that a slave could not be freed unless the slave owner guaranteed a security bond for the education, livelihood, and support of the freed slave in order to ensure that the former slave would not become a burden to the community or to the society. 25 Not only did such laws place extreme economic hardships on any slave owner who tried to free his slaves but they also provided stiff penalties for any slave owner who attempted to free slaves without abiding by these laws.) In 1723, a law was passed which forbid the emancipation of slaves under any circumstance-even by a last will and testament. The only exceptions were for cases of “meritorious service” by a slave, a determination to be made only by the State Governor and his Council on a case by case basis. 26 Needless to say, this law made the occasions for freeing slaves even more rare. In 1782, however, Virginia began to move in a new direction (for a short time) by passing a very liberal manumission law. As a result, “this restraint on the power of the master to emancipate his slave was removed, and since that time the master may emancipate by his last will or deed.” 27 (It was because of this law that George Washington was able to free his slaves in his last will and testament in 1799.) In 1806, unfortunately, the Virginia Legislature repealed much of that law, 28 and it became more difficult to emancipate slaves in a last will and testament:

It shall be lawful for any person, by his or her last will and testament, or by any other instrument in writing under his or her hand and seal . . . to emancipate and set free his or her slaves . . . Provided, also, that all slaves so emancipated, not being . . . of sound mind and body, or being above the age of forty-five years, or being males under the age of twenty one, or females under the age of eighteen years, shall respectively be supported and maintained by the person so liberating them, or by his or her estate. 29 (emphasis added)

That law even made it possible for a wife to reverse a portion of an emancipation made by her husband in his will:

And . . . a widow who shall, within one year from the death of her husband, declare in the manner prescribed by law that she will not take or accept the provision made for her . . . [is] entitled to one third part of the slaves whereof her husband died possessed, notwithstanding they may be emancipated by his will. 30

Furthermore, recall that Virginia law did not recognize slave families. Therefore, if a slave was freed, the law made it almost impossible for him to remain near his spouse, children, or his family members who had not been freed, for the law required that a freed slave promptly depart the State or else reenter slavery:

If any slave hereafter emancipated shall remain within this Commonwealth more than twelve months after his or her right to freedom shall have accrued, he or she shall forfeit all such right and may be apprehended and sold. 31

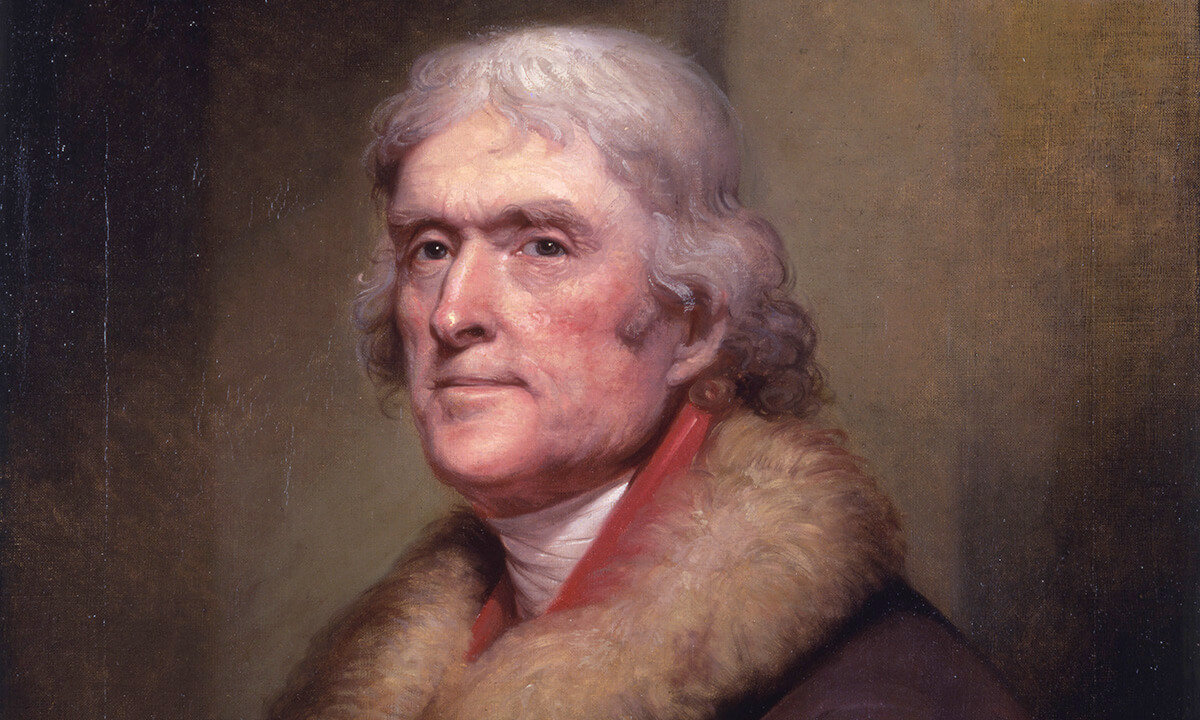

It was under difficult laws like these-under laws even more restrictive than those Washington had faced-that Jefferson was required to operate. Nevertheless, as a slave owner (he, like Washington, had inherited slaves), Jefferson maintained a consistent public opposition to slavery and assiduously labored to end slavery both in his State and in the nation. Jefferson’s efforts to end slavery were manifested years before the American Revolution. As he explained:

In 1769, I became a member of the legislature by the choice of the county in which I live [Albemarle County, Virginia], and so continued until it was closed by the Revolution. I made one effort in that body for the permission of the emancipation of slaves, which was rejected: and indeed, during the regal [crown] government, nothing [like this] could expect success. 32

Jefferson’s reference to the role of the British Crown in the continuance of slavery in Virginia is significant. Virginia, as a British colony, was subject to the laws of Great Britain, and those laws, executed by order of King George III, prevented every attempt to end slavery in America-or in any British colony. The specific law which the Crown invoked to strike down the attempts of the Colonies to free slaves had been passed in 1766 (three years before Jefferson’s election to office and his first efforts to end slavery), and declared:

[B]e it declared by the King’s most Excellent Majesty . . . that the said Colonies and plantations in America have been, are, and of right ought to be, subordinate unto and dependent upon the Imperial Crown and Parliament of Great Britain; and that the King’s Majesty . . . had, hath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the Colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever. And be it further declared and enacted by the authority aforesaid that all resolution, votes, orders, and proceedings whereby the power and authority of the Parliament of Great Britain to make laws and statutes . . . is denied, or drawn into question, are, and are hereby declared to be, utterly null and void to all intents and purposes whatsoever. 33

This law gave to the Crown the unilateral and unambiguous power to strike down any and all American laws on any subject whatsoever. Significantly, prior to the American Revolution some of the Colonies had voted to end slavery in their State, but those State laws had been struck down by the King. 34 This inability of individual Colonies to abolish slavery, even when they wished to do so, had caused Thomas Jefferson to include in the Declaration of Independence a listing of this grievance as one of the reasons propelling America to separate from Great Britain:

He [King George III] has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people which never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium [disgrace] of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian King of Great Britain. He has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain an execrable commerce [that is, he has opposed efforts to prohibit the slave trade], determined to keep open a market where men should be bought and sold. 35

Following America’s separation from Great Britain in 1776, individual States, for the first time in America’s history, were finally able to begin abolishing slavery. For example, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts abolished slavery in 1780, Connecticut and Rhode Island did so in 1784, Vermont in 1786, New Hampshire in 1792, New York in 1799, New Jersey in 1804, etc. Significantly, Thomas Jefferson helped end slavery in several States by his leadership on the Declaration of Independence, and he was also behind the first attempt to ban slavery in new territories. In 1784, as part of a committee of three, they introduced a law in the Continental Congress to ban slavery from the “western territory.” That proposal stated:

That after the year 1800 of the Christian era, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of the said States, otherwise than in punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted to have been personally guilty. 36

Unfortunately, that proposal fell one vote short of passage. Three years prior to that proposal, Jefferson had made known his feelings against slavery in his book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1781). That work, circulated widely across the nation, declared:

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But generally it is not sufficient. . . . The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances. And with what execration should the statesman be loaded who permits one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other. . . . And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that His justice cannot sleep for ever. . . . The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest. . . . [T]he way, I hone [is] preparing under the auspices of Heaven for a total emancipation. 37

Nearly twenty-five years later, Jefferson bemoaned that ending slavery had been a task even more difficult than he had imagined. In 1805, he lamented:

I have long since given up the expectation of any early provision for the extinguishment of slavery among us. [While] there are many virtuous men who would make any sacrifices to affect it, many equally virtuous persuade themselves either that the thing is not wrong or that it cannot be remedied. 38

Jefferson eventually recognized that slavery probably would never be ended during his lifetime. However, this did not keep him from continually encouraging others in their efforts to end slavery. For example, in 1814, he wrote Edward Coles:

Dear Sir, -Your favor of July 31 [a treatise opposing slavery] was duly received and was read with peculiar pleasure. The sentiments breathed through the whole do honor to both the head and heart of the writer. Mine on the subject of slavery of Negroes have long since been in possession of the public and time has only served to give them stronger root. The love of justice and the love of country plead equally the cause of these people, and it is a moral reproach to us that they should have pleaded it so long in vain. . . . From those of the former generation who were in the fullness of age when I came into public life, which was while our controversy with England was on paper only, I soon saw that nothing was to be hoped. Nursed and educated in the daily habit of seeing the degraded condition, both bodily and mental, of those unfortunate beings, not reflecting that that degradation was very much the work of themselves and their fathers, few minds have yet doubted but that they were as legitimate subjects of property as their horses and cattle. . . . In the first or second session of the Legislature after I became a member, I drew to this subject the attention of Col. Bland, one of the oldest, ablest, and most respected members, and he undertook to move for certain moderate extensions of the protection of the laws to these people. I seconded his motion, and, as a younger member, was more spared in the debate; but he was denounced as an enemy of his country and was treated with the grossest indecorum. From an early stage of our revolution, other and more distant duties were assigned to me so that from that time till my return from Europe in 1789, and I may say till I returned to reside at home in 1809, I had little opportunity of knowing the progress of public sentiment here on this subject. I had always hoped that the younger generation, receiving their early impressions after the flame of liberty had been kindled in every breast and had become as it were the vital spirit of every American, that the generous temperament of youth, analogous to the motion of their blood and above the suggestions of avarice, would have sympathized with oppression wherever found and proved their love of liberty beyond their own share of it. But my intercourse with them since my return has not been sufficient to ascertain that they had made towards this point the progress I had hoped. . . . Yet the hour of emancipation is advancing in the march of time. It will come, whether brought on by the generous energy of our own minds or by the bloody process. . . . This enterprise is for the young; for those who can follow it up and bear it through to its consummation. It shall have all my prayers, and these are the only weapons of an old man. . . . The laws do not permit us to turn them [the slaves] loose. . . . I hope then, my dear sir. . . . you will come forward in the public councils, become the missionary of this doctrine truly Christian; insinuate and inculcate it softly but steadily through the medium of writing and conversation; associate others in your labors, and when the phalanx [brigade or regiment] is formed, bring on and press the proposition perseveringly until its accomplishment. It is an encouraging observation that no good measure was ever proposed which, if duly pursued, failed to prevail in the end. . . . And you will be supported by the religious precept, “be not weary in well-doing” [Galatians 6:9]. That your success may be as speedy and complete, as it will be of honorable and immortal consolation to yourself, I shall as fervently and sincerely pray. 39

The next year, 1815, Jefferson wrote David Barrow:

The particular subject of the pamphlet [against slavery] you enclosed me was one of early and tender consideration with me, and had I continued in the councils [legislatures] of my own State, it should never have been out of sight. The only practicable plan I could ever devise is stated under the 14th Query of my Notes on Virginia, and it is still the one most sound in my judgment. . . . Some progress is sensibly made in it; yet not so much as I had hoped and expected. But it will yield in time to temperate and steady pursuit, to the enlargement of the human mind, and its advancement in science. We are not in a world ungoverned by the laws and the power of a superior agent. Our efforts are in His hand and directed by it; and He will give them their effect in His own time. Where the disease is most deeply seated, there it will be slowest in eradication. In the northern States, it was merely superficial and easily corrected. In the southern, it is incorporated with the whole system and requires time, patience, and perseverance in the curative process. That it may finally be effected and its progress hastened will be the last and fondest prayer of him who now salutes you with respect and consideration. 40

In 1820, Jefferson again reaffirmed his continuing opposition to slavery, declaring:

I can say, with conscious truth, that there is not a man on earth who would sacrifice more than I would to relieve us from this heavy reproach in any practicable way. The cession of that kind of property-for so it is misnamed is a bagatelle [possession] which would not cost me a second thought if, in that way, a general emancipation and expatriation could be effected; and gradually, and with due sacrifices, I think it might be. But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. 41

Then less than a year before his death, Jefferson responded to a young enthusiast:

At the age of eighty-two, with one foot in the grave and the other uplifted to follow it, I do not permit myself to take part in any new enterprises, even for bettering the condition of man, no even in the great one which is the subject of your letter and which has been through life that of my greatest anxieties. The march of events has not been such as to render its completion practicable with the limits of time allotted to me; and I leave its accomplishment as the work of another generation. And I am cheered when I see that on which it is devolved, taking it up with so much good will and such minds engaged in its encouragement. The abolition of the evil is not impossible; it ought never therefore to be despaired of. Every plan should be adopted, every experiment tried, which may do something towards the ultimate object. 42

And just weeks before his death, Jefferson reiterated:

On the question of the lawfulness of slavery, that is of the right of one man to appropriate to himself the faculties of another without his consent, I certainly retain my early opinions. 43

Since the State laws on slavery had significantly stiffened between the death of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson twenty-seven years later (as Jefferson had observed in 1814, “the laws do not permit us to turn them loose” 44), Jefferson was unable to do what Washington had done in freeing his slaves. However, Jefferson had gone well above and beyond other slave owners in that era in that he actually paid his slaves for the vegetables they raised and for the meat they obtained while hunting and fishing. Additionally, he paid them for extra tasks they performed outside their normal working hours and even offered a revolutionary profit sharing plan for the products that his enslaved artisans produced in their shops. 45

As a final note on Jefferson’s personal views and actions, Jefferson had occasionally offered the view that blacks were an inferior race to whites. For example, in his Notes on the State of Virginia in which he had expressed his ardent desire for the emancipation of blacks, he also offered his opinion that:

Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior. 46 [T]he blacks . . . are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind. 47

Notwithstanding such opinions, Jefferson was willing to be proved wrong. In fact, when Henri Gregoire in Paris read Jefferson’s views on the intellectual capacity of blacks, he sent to Jefferson several examples of blacks for the purpose of disproving Jefferson’s thesis. Jefferson responded to him:

Be assured that no person living wishes more sincerely than I do to see a complete refutation of the doubts I have myself entertained and expressed on the grade of understanding allotted to them by nature and to find that in this respect they are on a par with ourselves. My doubts were the result of personal observation on the limited sphere of my own State, where the opportunities for the development of their genius were not favorable, and those of exercising it still less so. I expressed them therefore with great hesitation; but whatever be their degree of talent it is no measure of their rights. Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding, he was not therefore lord of the person or property of others. On this subject they are gaining daily in the opinions of nations, and hopeful advances are making towards their reestablishment on an equal footing with the other colors of the human family. I pray you therefore to accept my thanks for the many instances you have enabled me to observe of respectable intelligence in that race of men, which cannot fail to have effect in hastening the day of their relief. 48 (emphasis added)

And to Benjamin Banneker (a former slave distinguished for his scientific and mathematical talents, the publisher of an almanac, and one of the surveyors who laid out the city of Washington, D. C.), Jefferson wrote:

I thank you sincerely for your letter . . . and for the almanac it contained. Nobody wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren talents equal to those of the other colors of men. . . . I have taken the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet, Secretary of the Academy of Sciences at Paris, and member of the Philanthropic Society, because I considered it as a document to which your color had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them. 49

When considering Jefferson’s views on the capacity of blacks (views apparently not stridently held), Jefferson’s actions to end slavery must be seen as even more remarkable. His efforts to achieve full freedom for a race he perhaps considered inferior indicate not only the sincerity of his belief that all men were indeed created equal but also his abiding conviction-expressed at the age of 77, only five years before his death-that “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people are to be free.” 50

While today both Washington and Jefferson are roundly condemned for owning slaves, it is nevertheless true that they both laid the first seeds for the abolition of slavery in the United States. One historian summarized their pioneer efforts in these words:

With the minds of thoughtful men thoroughly wakened on the subject of human rights [shortly before the American Revolution], it was impossible not to reflect on the wrongs of the slaves, incomparably worse than those against which their masters had taken up arms. As the political institutions of the young Federation were remolded, so grave a matter as slavery could not be ignored. Virginia in 1772 voted an address to the King remonstrating against the continuance of the African slave trade. The address was ignored, and Jefferson in the first draft of the Declaration alleged this as one of the wrongs suffered at the hands of the British government, but his colleagues suppressed the clause. In 1778, Virginia forbade the importation of slaves into her ports. The next year Jefferson proposed to the Legislature an elaborate plan for gradual emancipation, but it failed of consideration. Maryland followed Virginia in forbidding the importation of slaves from Africa. Virginia in 1782 passed a law by which manumission of slaves, which before had required special legislative permission, might be given at the will of the master. For the next ten years manumission went on at the rate of 8000 a year. . . . Jefferson planned nobly for the exclusion of slavery from the whole as yet unorganized domain of the nation a measure which would have belted the slave States with free territory, and so worked toward universal freedom. The sentiment of the time gave success to half his plan. His proposal in the ordinance of 1784 missed success in the Continental Congress by the vote of a single State. The principle was embodied in the ordinance of 1787. 51

Significantly it was the efforts of both Washington and Jefferson, and especially the documents which Jefferson had written, that were so heavily relied on by later abolitionists such as John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln in their efforts to end slavery. For example, John Quincy Adams, called the “Hell Hound of Abolition” for his extensive endeavors against that institution, regularly invoked the efforts of the Virginia patriots, particularly Jefferson, to justify his own crusade against slavery. In fact, in a speech in 1837, John Quincy Adams declared:

The inconsistency of the institution of domestic slavery with the principles of the Declaration of Independence was seen and lamented by all the southern patriots of the Revolution; by no one with deeper and more unalterable conviction than by the author of the Declaration himself [Jefferson]. No charge of insincerity or hypocrisy can be fairly laid to their charge. Never from their lips was heard one syllable of attempt to justify the institution of slavery. They universally considered it as a reproach fastened upon them by the unnatural step-mother country [Great Britain] and they saw that before the principles of the Declaration of Independence, slavery, in common with every other mode of oppression, was destined sooner or later to be banished from the earth. Such was the undoubting conviction of Jefferson to his dying day. In the Memoir of His Life, written at the age of seventy-seven, he gave to his countrymen the solemn and emphatic warning that the day was not distant when they must hear and adopt the general emancipation of their slaves. 52

And Daniel Webster, whose efforts in the U. S. Senate to end slavery paralleled those of John Quincy Adams in the U. S. House, also invoked the efforts of Washington and Jefferson to bolster his own position that slavery must be ended. In fact, on January 29, 1845, Webster was one of three individuals who helped frame an “Address to the People of the United States’ promulgated by the Anti-Texas Convention. . . . [to] lift our public sentiment to a new platform of anti-slavery.” 53 Part of that address declared:

Soon after the adoption of the Constitution, it was declared by George Washington to be “among his first wishes to see some plan adopted by which slavery might be abolished by law;” and in various forms in public and private communications, he avowed his anxious desire that “a spirit of humanity,” prompting to “the emancipation of the slaves,” “might diffuse itself generally into the minds of the people;” and he gave the assurance, that “so far as his own suffrage would go,” his influence should not be wanting to accomplish this result. By his last will and testament he provided that “all his slaves should receive their freedom,” and, in terms significant of the deep solicitude he felt upon the subject, he “most pointedly and most solemnly enjoined” it upon his executors “to see that the clause respecting slaves, and every part thereof, be religiously fulfilled, without evasion, neglect, or delay.” No language can be more explicit, more emphatic, or more solemn, than that in which Thomas Jefferson, from the beginning to the end of his life, uniformly declared his opposition to slavery. “I tremble for my country,” said he, “when I reflect that God is just-that His justice cannot sleep forever.” * * “The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.” In reference to the state of public feeling as influenced by the Revolution, he said, “I think a change already perceptible since the origin of the Revolution;” and to show his own view of the proper influence of the spirit of the Revolution upon slavery, he proposed the searching question: “Who can endure toil, famine, stripes, imprisonment, and death itself, in vindication of his own liberty, and the next moment be deaf to all those motives whose power supported him through his trial, and inflict on his fellow men a bondage, one hour of which is fraught with more misery than ages of that which he rose in rebellion to oppose?” “We must wait,” he added, “with patience, the workings of an overruling Providence, and hope that that is preparing the deliverance of these our suffering brethren. When the measure of their tears shall be full-when their tears shall have involved Heaven itself in darkness, doubtless a God of justice will awaken to their distress, and by diffusing light and liberality among their oppressors, or at length, by his exterminating thunder, manifest his attention to things of this world, and that they be not left to the guidance of blind fatality!” Towards the close of his life, Mr. Jefferson made a renewed and final declaration of his opinion by writing thus to a friend: “My sentiments on the subject of the slavery of Negroes have long since been in possession of the public, and time has only served to give them stronger root. The love of justice and the love of country plead equally the cause of these people; and it is a moral reproach to us that they should have pleaded it so long in vain and should have produced not a single effort-nay, I fear, not much serious willingness to relieve them and ourselves from our present condition of moral and political reprobation.” 54

And Abraham Lincoln specifically invoked the words and efforts of Thomas Jefferson to justify his own crusade to end slavery and achieve civil rights and equality for blacks. For example, Lincoln invoked Jefferson to condemn the Kansas-Nebraska Act permitting territories that allowed slavery to become States in the Union:

Mr. Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, and otherwise a chief actor in the Revolution; then a delegate in Congress; afterwards twice President; who was, is, and perhaps will continue to be, the most distinguished politician of our history; a Virginian by birth and continued residence, and withal, a slave-holder; conceived the idea of taking that occasion to prevent slavery ever going into the northwestern territory. . . . and in the first Ordinance (which the acts of Congress were then called) for the government of the territory, provided that slavery should never be permitted therein. This is the famed ordinance of ‘87 so often spoken of. . . . Thus, with the author of the Declaration of Independence, the policy of prohibiting slavery in new territory originated. Thus, away back of the Constitution, in the pure, fresh, free breath of the Revolution, the State of Virginia and the national Congress put that policy in practice. Thus through sixty odd of the best years of the republic did that policy steadily work to its great and beneficent end. And thus, in those . . . States, and five millions of free, enterprising people, we have before us the rich fruits of this policy. But now new light breaks upon us. Now Congress declares this ought never to have been; and the like of it, must never be again. . . . We even find some men who drew their first breath, and every other breath of their lives, under this very restriction [against slavery], now live in dread of absolute suffocation if they should be restricted in the “sacred right” of taking slaves to Nebraska. That perfect liberty they sigh for-the “liberty” of making slaves of other people-Jefferson never thought of. 55

On other occasions, Lincoln quoted Jefferson’s words from the Declaration of Independence, pointing out that Jefferson had . . .

. . . established these great self-evident truths that when in the distant future some man, some faction, some interest, should set upon the doctrine that none but rich men, or none but white men, were entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, their posterity might look up again to the Declaration of Independence and take courage to renew the battle which their fathers began. . . . Now, my countrymen, if you have been taught doctrines conflicting with the great landmarks of the Declaration of Independence; if you have listened to suggestions which would take away from its grandeur and mutilate the fair symmetry of its proportions; if you have been inclined to believe that all men are not created equal in those inalienable rights enumerated by our chart of liberty; let me entreat you to come back. . . . [C]ome back to the truths that are in the Declaration of Independence. 56

It is undebatable that the early efforts and words both of George Washington and of Thomas Jefferson provided one of the strongest platforms on which later generations of abolitionists, and some of their most notable orators, erected their arguments. While it is difficult for today’s critics of Washington and Jefferson to understand the culture of America two centuries ago, it is nevertheless true that both Washington and Jefferson were influential in slowly turning that culture in a direction which-generations later-eventually secured equal civil rights for all Americans, regardless of their color.

Endnotes

1 John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, Henry P. Johnston, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891), Vol. III, p. 342, to the English Anti-Slavery Society in June 1788.

2 Thomas R. R. Cobb, An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in the United States of America, to Which is Prefixed an Historical Sketch of Slavery (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson & Co., 1858), Vol. I, p. 169).

3 Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Paul Leicester Ford, editor (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), Vol. XI, pp. 470-471, to David Barrow on May 1, 1815.

4 Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington, D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1903), Vol. I, p. 28, from his Autobiography; see also James Madison, The Papers of James Madison (Washington: Langtree and O’Sullivan, 1840), Vol. 111, p. 1395, August 22, 1787; see also James Madison, The Writings of James Madison, GaiIlard Hunt, editor, (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910), Vol. IX, p. 2, to Robert Walsh on November 27, 1819.

5 Cobb, Vol. 1, p. 172.

6 George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Washington, D. C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1936), Vol. 38, p. 408, to Robert Morris on April 12, 1786.

7 George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, Jared Sparks (Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1837), Vol. 11, p. 494.

8 Washington, Writings (1936), Vol. 28, p. 424, to Marquis de Lafayette on May 10, 1786.

9 Washington, Writings (1936), Vol. 36, p. 2, to Lawrence Lewis on August 4, 1797.

10 George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, 1748-1799, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, published for the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1925), Vol. I, p. 117 (on January 25, 1760, Washington sought to purchase a joiner, a bricklayer, and a gardener), p. 278 (on July 25, 1768, Washington purchased a bricklayer), and p. 383 (on June 11, 1770, Washington purchased two slaves). Additional information on the total number of slaves Washington urchased, and the dates of those purchases, was provided by research specialist Mary Thompson of Mt. Vernon.

11 Washington, Writings (1939), Vol. 29, p. 5, to John Francis Mercer on September 9, 1786.

12 Washington, Writings (1939), Vol. 34, p. 47, to Alexander Spotswood on November 23, 1794.

13 Washington, Writings (1940), Vol. 37, p. 338, to Robert Lewis on August 18, 1799.

14 James Thomas Flexner, George Washington: Anguish and Farewell, 1793-1799 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1972), p. 342.

15 Washington, Writings (1940), Vol. 37, p. 338, to Robert Lewis on August 18, 1799.

16 Washington, Writings (1940), Vol. 37, p. 338, to Robert Lewis on August 18, 1799.

17 Mount Vernon, “George Washington and Slavery. Slave Census, 1996,” www.mountvernon.org/education/slavery/census.html.

18 Washington, Writings (1931), Vol. 111, p. 285, to Edward Montague on April 5, 1775.

19 George Washington, The Last Will and Testament of George Washington and Schedule of his Property to Which is Appended the Last Will and Testament of Martha Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Washington, D. C.: The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, 1939), pp. 2-4.

20 Washington, Writings (1931), Vol. 4, pp. 360-361, to Phillis Wheatley on February 28, 1776.

21 Edward Johnson, A School History of the Negro Race in America, from 1619 to 1890, with a Short Introduction as to the Origin of the Race; Also a Short Sketch of Liberia (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1891), p. 68.

22 William C. Nell, Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1852), pp. 39-40, taken from the Appendix, quoting Rev. Henry F. Harrington, “Anecdotes of Washington,” Godeys Ladys Book, June, 1849.

23 Nell, Services, p. 38.

24 W. O. Blake, The History of Slavery and the Slave Trade; Ancient and Modern. The Forms of Slavery that Prevailed in Ancient Nations, Particularly in Greece and Rome. The African Slave Trade and the Political History of Slavery in the United States (Ohio: J. & H. Miller, 1857), pp. 373-374.

25 Blake, The History of Slavery and the Slave Trade, p. 381.

26 George M. Stroud, A Sketch of the Laws Relating to Slavery in the Several States of the United States of America (Philadelphia: Henry Longstreth, 1856), pp. 236-237.

27 Stroud, A Sketch of the Laws Relating to Slavery, pp. 236-237.

28 Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time: Volume Six, The Sage of Monticello (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1981), p. 319.

29 The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia: Being A Collection of all Such Acts of the General Assembly, of a Public and Permanent Nature, as are Now in Force (Richmond: Printed by Thomas Ritcher, 1819), pp. 433-436.

30 The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia, pp. 433-436.

31 The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia, pp. 433-436; see also, Stroud, A Sketch of the Laws Relating to Slavery, pp. 236-237.

32 Jefferson, Writings (1903), Vol. I, p. 4, from his Autobiography.

33 Anno Regni Georgii III. Regis Magne Britanniæ, Franciæ, & Hiberniæ, Sexto (London: Printed by Mark Baskett, Printer to the King’s most Excellent Majesty; and by the assigns of Robert Baskett, 1766).

34 Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, Jared Sparks, editor (Boston: Tappan, Whittemore, and Mason, 1839), Vol. VIII, p. 42, to the Rev. Dean Woodward on April 10, 1773.

35 Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1906), Vol. V, 1776, June 5-October 8, p. 498, Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence.

36 Journals of the Continental Congress, Volume XXVI, pp. 118-119, Monday, March 1, 1784.

37 Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (New York: M. L. & W. A. Davis, 1794, Second Edition), pp. 240-242, Query XVIII.

38 Jefferson, Works (1905), Vol. X, p. 126, to William A. Burwell on January 28, 1805.

39 Jefferson, Works (1905), Vol. XI, pp. 416-420, to Edward Coles on August 25, 1814.

40 Jefferson, Works (1905), Vol. XI, pp. 470-471, to David Barrow on May 1, 1815.

41 Jefferson, Works (1905), Vol. XII, pp. 158-159, to John Holmes on April 22, 1820.

42 Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XVI, pp. 119-120, to Miss Frances Wright on August 7, 1825.

43 Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XVI, pp. 162-163, to the Hon. Edward Everett on April 8, 1826.

44 The Constitutions of the Sixteen States (Boston: Manning and Loring, 1797), p. 249, Vermont, 1786, Article I, “Declaration of Rights.”

45 Information obtained from Monticello, at www.monticello.org/jefferson/plantation/dig.html.

46 Jefferson, Writings (1903), Vol. II, p. 194, from Query XIV of Notes on Virginia.

47 Jefferson, Writings (1903), Vol. II, p. 201, from Query XIV of Notes on Virginia.

48 Jefferson, Writings (1904), Vol. XII, p. 255, to M. Henri Gregoire on February 25, 1809; see also Vol. XII, p. 322, to Joel Barlow on October 8, 1809, wherein, speaking on the same subject, he declares, “It is impossible for doubt to have been more tenderly or hesitatingly expressed than that was in the Notes of Virginia, and nothing was or is farther from my intentions that to enlist myself as the champion of a fixes opinion where I have only expressed a doubt.”

49 Jefferson, Writings (1903), Vol. VIII, pp. 241-242, to Benjamin Banneker on August 30, 1791.

50 Jefferson, Writings (1903), Vol. I, p. 72, from Jefferson’s Autobiography.

51 George S. Merriam, The Negro and the Nation: A History of American Slavery and Enfranchisement (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1906), pp. 8-10.

52 John Quincy Adams, An Oration Delivered Before The Inhabitants Of The Town Of Newburyport at Their Request on the Sixty-First Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1837 (Newburyport: Charles Whipple, 1837), p. 50

53 Daniel Webster, The Writings and Speeches of Daniel Webster Hitherto Uncollected (Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1903), Vol. 111, pp. 192-193, n., “Address on the Annexation of Texas,” January 29, 1845.

54 Daniel Webster, Writings . . . Hitherto Uncollected, Vol. III, pp. 204-205, “Address on the Annexation of Texas,” January 29, 1845.

55 Abraham Lincoln, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Roy P. Basler, editor (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953), Vol. II, pp. 250-251, from his speech at Peoria, Illinois, on October 16, 1854.

56 Lincoln, Works, Vol. II, p. 546, from his speech on August 17, 1858.