David Barton 2008

While uninformed laymen erroneously believe the theory of evolution to be a product of Charles Darwin in his first major work of 1859 (The Origin of Species), the historical records are exceedingly clear that the evolution-creation-intelligent design debate was largely formulated well before the birth of Christ. Numerous famous writings have appeared on the topic for almost two thousand years; in fact, our Founding Fathers were well-acquainted with these writings and therefore the principle theories and teachings of evolution – as well as the science and philosophy both for and against that thesis – well before Darwin synthesized those centuries-old teachings in his writings.

Nobel-Prize winner Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) explains: “The general idea of evolution is very old; it is already to be found in Anaximander (sixth century B.C.). . . . [and] Descartes [1596-1650], Kant [1724-1804], and Laplace [1749-1827] had advocated a gradual origin for the solar system in place of sudden creation.”1 Professor Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857-1935), a zoologist and paleontologist, agrees, declaring that there are “ancient pedigrees for all that we are apt to consider modern. Evolution has reached its present fullness by slow additions in twenty-four centuries.”2 He continues, “Evolution as a natural explanation of the origin of the higher forms of life . . . developed from the teaching of Thales [624-546 B.C.] and Anaximander [610-546 B.C.] into those of Aristotle [384-322 B.C.]. . . . and it is startling to find him, over two thousand years ago, clearly stating, and then rejecting, the theory of the survival of the fittest as an explanation of the evolution of adaptive structures.”3 And British anthropologist Edward Clodd (1840-1930) similarly affirms that, “The pioneers of evolution – the first on record to doubt the truth of the theory of special creation, whether as the work of departmental gods or of one Supreme Deity, matters not – lived in Greece about the time already mentioned: six centuries before Christ.”4

For example, Anaximander (610-546 B.C.) introduced the theory of spontaneous generation; Diogenes (412-323 B.C.) introduced the concept of the primordial slime; Empedocles (495-455 B.C.) introduced the theory of the survival of the fittest and of natural selection; Deomocritus (460-370 B.C.) advocated the mutability and adaptation of species; the writings of Lucretius (99-55 B.C.) announced that all life sprang from “mother earth” rather than from any specific deity; Bruno (1548-1600) published works arguing against creation and for evolution in 1584-85; Leibnitz (1646-1716) taught the theory of intermedial species; Buffon (1707-1788) taught that man was a quadruped ascended from the apes, about which Helvetius also wrote in 1758; Swedenborg (1688-1772) advocated and wrote on the nebular hypothesis (the early “big bang”) in 1734, as did Kant in 1755; etc. It is a simple fact that countless works for (and against) evolution had been written for over two millennia prior to the drafting of our governing documents and that much of today’s current phraseology surrounding the evolution debate was familiar rhetoric at the time our documents were framed.

In fact, Dr. Henry Osborn (1857-1935), curator of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, identifies four periods of evolution: I. Greek Evolution – 640 B.C. to 1600 A.D.; II. Modern Evolution – 1600-1800 A.D.; III. Modern Inductive Evolution – 1730-1850 A.D.; and IV. Modern Inductive Evolution – 1858 to the present.5 He describes the third period in the history of evolution – the period in which our Framers lived – as a period which produced the pro-evolution writings of “Linnaeus, Buffon, E[rasmus] Darwin, Lamarck, Goethe, Treviranus, Geof. St. Hilaire, St. Vincent, Is. St. Hilaire. Miscellaneous writers: Grant, Rafinesque, Virey, Dujardin, d’Halloy, Chevreul, Godron, Leidy, Unger, Carus, Lecoq, Schaafhausen, Wolff, Meckel, Von Baer, Serres, Herbert, Buch, Wells, Matthew, Naudin, Haldeman, Spencer, Chambers, Owen.”6

The debate over the origins of man has always been between a theistic and a non-theistic approach; and among those who embrace the theistic approach have been found (and still are found) three distinct sub-approaches: (1) intelligent-design (that which exists came into being by divine guidance, but the period of time required or the specifics of the process are unsettled, possibly unprovable, and therefore remain debatable); (2) theistic evolution (that which exists came into being over a long, slow passing of time through natural laws and processes but under divine guidance); and (3) special creation (that which exists came into being in six literal days). This, then, makes four separate historic approaches to the origins of man: three theistic, and one non-theistic.

In the non-theistic camp, Empedocles (495-435 B.C.) was the father and original proponent of the evolution theory, followed by advocates such as Democritus (460-370 B.C. ), Epicurus (342-270 B.C.), Lucretius (98-55 B.C.), Abubacer (1107-1185 A.D.), Bruno (1548-1600), Buffon (1707-1788), Helvetius (1715-1771), Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), Lamarck (1744-1829), Goethe (1749-1832), Lyell (1797-1875), etc.

In the theistic camp, Anaxigoras (500-428 B.C.) was the father of intelligent design; that same belief was also expounded by such distinguished scientists and philosophers Descartes (1596-1650), Harvey (1578-1657), Newton (1642-1727), Kant (1729-1804), Mendel (1822-1884), Cuvier (1769-1827), Agassiz (1807-1873), etc. Significantly, even Charles Darwin (1809-1882), strongly influenced by the writings of Paley (1743- 1805),7 embraced the intelligent design position at the time that he wrote his celebrated word, explaining:

Another source of conviction in the existence of God, connected with the reason and not with the feelings, impresses me as having much more weight. This follows from the extreme difficulty, or rather impossibility, of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe, including man with his capacity of looking far backwards and far into futurity, as the result of blind chance or necessity. When thus reflecting I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent mind in some degree analogous to that of man; and I deserve to be called a Theist. This conclusion was strong in my mind about the time, as far as I can remember, when I wrote the Origin of Species.8

John Dewey, an ardent 20th century proponent of Darwinism, explained why the intelligent design position – scientifically speaking – was reasonable:

The marvelous adaptation of organisms to their environment, of organs to the organism, of unlike parts of a complex organ (like the eye) to the organ itself; the foreshadowing by lower forms of the higher; the preparation in earlier stages of growth for organs that only later had their functioning – these things are increasingly recognized with the progress of botany, zoology, paleontology, and embryology. Together, they added such prestige to the design argument that by the later eighteenth century it was, as approved by the sciences of organic life, the central point of theistic and idealistic philosophy.9

(This position of intelligent design, also called the anthropic or teleological view, is now embraced by an increasing number of contemporary distinguished scientists, non-religious though many of them claim to be.10)

The second camp within the theistic approach is theistic evolution, which was first propounded by Aristotle (384-322 B.C.). Other prominent expositors of this view included Gregory of Nyssa (331-396 A.D.), Augustine of Hippo (354-430 A.D.), St. Gregory the First (540-604 A.D.), St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), Leibnitz (1646-1716), Swedenborg (1688-1772), Bonnet (1720-1793), and numerous contemporary scientists. In fact, many of Darwin’s contemporaries embraced this view, believing that “natural selection could be the means by which God has chosen to make man.”11

As confirmed by Dr. James Rachels, professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham: Mivart [1827-1900, a professor in Belgium] became the leader of a group of dissident evolutionists who held that although man’s body might have evolved by natural selection, his rational and spiritual soul did not. At some point God had interrupted the course of human history to implant man’s soul in him, making him something more than merely a former ape. . . . Wallace [1823-1913, who advocated natural selection prior to Darwin] took a view very similar to that of Mivart: he held that the theory of natural selection applies to humans, but only up to a point. Our bodies can be explained in this way, but not our brains. Our brains, he said, have powers that far outstrip anything that could have been produced by natural selection. Thus he concluded that God had intervened in the course of human history to give man the “extra push” that would enable him to reach the pinnacle on which he now stands. . . . Natural selection, while it explained much, could not explain everything; in the end God must be brought in to complete the picture.12

In fact, Clarence Darrow himself (the lead attorney during the famous Scopes Monkey Trial in 192513), admitted during the trial that this was a prominent position of many in that day;14 and Dudley Malone, Darrow’s co-counsel, even declared:

We shall show by the testimony of men learned in science and theology that there are millions of people who believe in evolution and in the stories of creation as set forth in the Bible and who find no conflict between the two.15

Interestingly, writers who chronicle the centuries-long history of the evolution debate16 confirm that there have always been numerous evolutionists in both the theistic and the non-theistic camps, and much of the proceedings in the Scopes trial reaffirmed that a belief in evolution was not incompatible with teaching theistic origins and a belief in a divine creator.

The third camp, special (or literal) creation, was championed by Francisco Suarez (1548-1617) and later by Pasteur (1822-1895) as well as by subsequent contemporary scientists.

Significantly, then, the history of this controversy through recent years and even previous centuries makes clear that subsequent scientific discovery across the centuries has not yet significantly altered any of these four views. Therefore, it was not in the absence of knowledge about the debate over evolution but rather in its presence, that our Framers made the decision to incorporate in our governing documents the principle of a creator.

One example affirming the Framers’ view on this subject is provided by Thomas Paine.

Thomas Paine

Although Paine was the most openly and aggressively anti-religious of the Founders, in his 1787 “Discourse at the Society of Theophilanthropists in Paris,” Paine nevertheless forcefully denounced the French educational system which taught students that man was the result of prehistoric cosmic accidents, or had developed from some other species:

It has been the error of schools to teach astronomy, and all the other sciences and subjects of natural philosophy, as accomplishments only; whereas they should be taught theologically, or with reference to the Being who is the Author of them: for all the principles of science are of divine origin. Man cannot make, or invent, or contrive principles; he can only discover them, and he ought to look through the discovery to the Author.

When we examine an extraordinary piece of machinery, an astonishing pile of architecture, a well-executed statue, or a highly-finished painting where life and action are imitated, and habit only prevents our mistaking a surface of light and shade for cubical solidity, our ideas are naturally led to think of the extensive genius and talent of the artist.When we study the elements of geometry, we think of Euclid. When we speak of gravitation, we think of Newton. How, then, is it that when we study the works of God in creation, we stop short and do not think of God? It is from the error of the schools in having taught those subjects as accomplishments only and thereby separated the study of them from the Being who is the Author of them. . . .

The evil that has resulted from the error of the schools in teaching natural philosophy as an accomplishment only has been that of generating in the pupils a species of atheism. Instead of looking through the works of creation to the Creator Himself, they stop short and employ the knowledge they acquire to create doubts of His existence. They labor with studied ingenuity to ascribe everything they behold to innate properties of matter and jump over all the rest by saying that matter is eternal.

And when we speak of looking through nature up to nature’s God, we speak philosophically the same rational language as when we speak of looking through human laws up to the power that ordained them.

God is the power of first cause, nature is the law, and matter is the subject acted upon.

But infidelity, by ascribing every phenomenon to properties of matter, conceives a system for which it cannot account and yet it pretends to demonstrate.17

Paine certainly did not advocate this position as a result of religious beliefs or of any teaching in the Bible, for he believed that “the Bible is spurious” and “a book of lies, wickedness, and blasphemy.”18 Yet, this anti-Bible founder was nevertheless a strong supporter of teaching the theistic origins of man. Many other Founding Fathers also held clear positions on this issue.

John Quincy Adams

It is so obvious to every reasonable being, that he did not make himself; and the world which he inhabits could as little make itself that the moment we begin to exercise the power of reflection, it seems impossible to escape the conviction that there is a Creator. It is equally evident that the Creator must be a spiritual and not a material being; there is also a consciousness that the thinking part of our nature is not material but spiritual – that it is not subject to the laws of matter nor perishable with it. Hence arises the belief, that we have an immortal soul; and pursuing the train of thought which the visible creation and observation upon ourselves suggest, we must soon discover that the Creator must also he the Governor of the universe – that His wisdom and His goodness must be without bounds – that He is a righteous God and loves righteousness – that mankind are bound by the laws of righteousness and are accountable to Him for their obedience to them in this life, according to their good or evil deeds.19

But the first words of the Bible are, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” The blessed and sublime idea of God as the creator of the universe – the Source of all human happiness for which all the sages and philosophers of Greece and Rome groped in darkness and never found – is recalled in the first verse of the book of Genesis. I call it the source of all human virtue and happiness because when we have attained the conception of a Being Who by the mere act of His will created the world, it would follow as an irresistible consequence (even if we were not told that the same Being must also be the governor of his own creation) that man, with all other things, was also created by Him, and must hold his felicity and virtue on the condition of obedience to His will.20

Benjamin Franklin

It might be judged an affront to your understandings should I go about to prove this first principle: the existence of a Deity and that He is the Creator of the universe; for that would suppose you ignorant of what all mankind in all ages have agreed in. I shall therefore proceed to observe that He must be a being of infinite wisdom (as appears in His admirable order and disposition of things), whether we consider the heavenly bodies, the stars and planets and their wonderful regular motions; or this earth, compounded of such an excellent mixture of all the elements; or the admirable structure of animate bodies of such infinite variety and yet every one adapted to its nature and the way of life is to be placed in, whether on earth, in the air, or in the water, and so exactly that the highest and most exquisite human reason cannot find a fault; and say this would have been better so, or in such a manner which whoever considers attentively and thoroughly will be astonished and swallowed up in admiration.21

That the Deity is a being of great goodness appears in His giving life to so many creatures, each of which acknowledges it a benefit by its unwillingness to leave it; in His providing plentiful sustenance for them all and making those things that are most useful, most common and easy to be had, such as water (necessary for almost every creature to drink); air (without which few could subsist); the inexpressible benefits of light and sunshine to almost all animals in general; and to men, the most useful vegetables, such as corn, the most useful of metals, as iron, & c.; the most useful animals as horses, oxen, and sheep, He has made easiest to raise or procure in quantity or numbers; each of which particulars, if considered seriously and carefully, would fill us with the highest love and affection. That He is a being of infinite power appears in His being able to form and compound such vast masses of matter (as this earth, and the sun, and innumerable stars and planets), and give them such prodigious motion and yet so to govern them in their greatest velocity as that they shall not fly out of their appointed bounds not dash one against another for their mutual destruction. But it is easy to conceive His power, when we are convinced of His infinite knowledge and wisdom. For, if weak and foolish creatures as we are, but knowing the nature of a few things, can produce such wonderful effects, . . . what power must He possess, Who not only knows the nature of everything in the universe but can make things of new natures with the greatest ease and at His pleasure! Agreeing, then, that the world was a first made by a Being of infinite wisdom, goodness, and power, which Being we call God.22

John Adams

When I was in England from 1785 to 1788, I may say I was intimate with Dr. Price [Richard Price was a theologian and a strong British supporter of American rights and independence, with Congress bestowing on him an American citizenship in 1778]. I had much conversation with him at his own house, at my houses, and at the house and tables of many friends. In some of our most unreserved conversations when we have been alone, he has repeatedly said to me, “I am inclined to believe that the Universe is eternal and infinite. It seems to me that an eternal and infinite effect must necessarily flow from an eternal and infinite Cause; and an infinite Wisdom, Goodness, and Power that could have been induced to produce a Universe in time must have produced it from eternity.” “It seems to me, the effect must flow from the Cause”… It has been long – very long – a settled opinion in my mind that there is now, never will be, and never was but one Being who can understand the universe, and that it is not only vain but wicked for insects [like us] to pretend to comprehend it.23

James Wilson

When we view the inanimate and irrational creation around and above us, and contemplate the beautiful order observed in all its motions and appearances, is not the supposition unnatural and improbable that the rational and moral world should be abandoned to the frolics of chance or to the ravage of disorder? What would be the fate of man and of society was every one at full liberty to do as he listed without any fixed rule or principle of conduct – without a helm to steer him, a sport of the fierce gusts of passion and the fluctuating billows of caprice?24

Daniel Webster

The belief that this globe existed from all eternity (or never had a beginning), never obtained a foothold in any part of the world or in any age. Even the infidel writer of modern times, however, in the pride of argument they may have asserted it but believed it not, for they could not help perceiving that if mankind, with their inherently intellectual powers and natural capacities for improvement, had inhabited this earth for millions of years, the present inhabitants would not only be vastly more intelligent than we now find them but there would be vestiges of the former races to be found in every inhabitable part of the globe, floods and earthquakes notwithstanding. Unless we adopt Lord Monboddo’s [1714-1799, a Scottish legal scholar and pioneer anthropologist who advocated evolution through natural selection and man’s ascent from chimps] supposition that mankind were originally monkeys, it is impossible to admit the idea that they could have existed millions of years without making more discoveries and improvements than the early histories of nations warrant us to believe they had done. The belief in an uncreated, self-existent intelligent First Cause takes possession of our minds whether we will or not, because if man could not create himself, nothing else could; and matter, if it were not external, could produce nothing but matter; it could never produce thought nor free will nor consciousness. There must have been, therefore, a time when this globe and its inhabitants did not exist. The question then arises, what gave it existence? We answer God, the great First Cause of all things. What is God? We know not. We know Him only through His creation and His revelation. What do these teach us? They teach us, first this; incomprehensible power, next His infinite mind, and lastly His universal benevolence or goodness. These terms express all that we can know or believe of Him.25

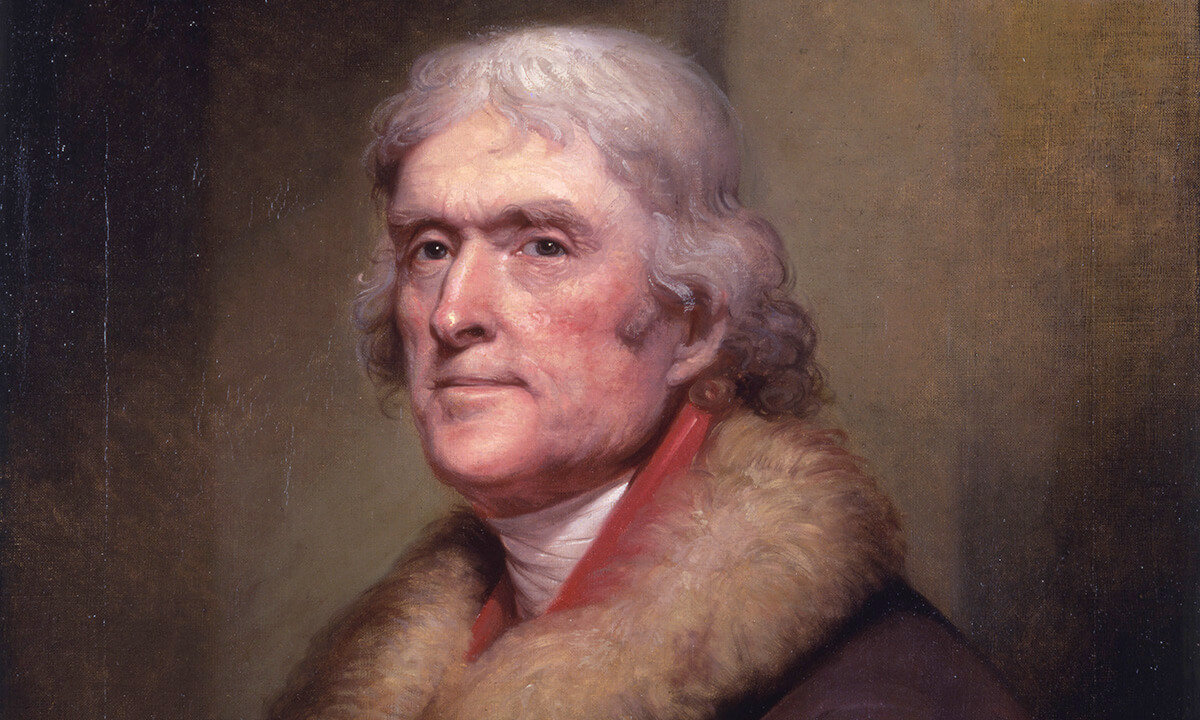

Thomas Jefferson

[W]hen we take a view of the universe in its parts, general or particular, it is impossible for the human mind not to perceive and feel a conviction of design, consummate skill, and indefinite power in every atom of its composition. The movements of the heavenly bodies, so exactly held in their course by the balance of centrifugal and centripetal forces; the structure of our earth itself, with its distribution of lands, waters, and atmosphere; animal and vegetable bodies, examined in all their minutest particles; insects, mere atoms of life, yet as perfectly organized as man or mammoth; the mineral substances, their generation and uses – it is impossible, I say, for the human mind not to believe that there is, in all this, design, cause, and effect, up to an ultimate cause, a Fabricator of all things from matter and motion, their Preserver and Regulator while permitted to exist in their present forms, and their regeneration into new and other forms. We see, too, evident proofs of the necessity of a superintending power, to maintain the universe in its course and order.26

(A longer and more extensive piece on the history of evolution and the Founding Fathers can be read in David Barton’s law review article published for Regent Lawschool on the 75th anniversary of the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial. That piece, entitled “Evolution and the Law: A Death Struggle Between Two Civilizations,” is accessible here.)

Endnotes

1 Bertrand Russell, Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1948), 33-34.

2 Henry Fairfield Osborn, From the Greeks to Darwin (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924), 1.

3 Osborn, From the Greeks to Darwin (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924), 6.

4 Edward Clodd, Pioneers of Evolution From Thales to Huxley (New York: Books for Libraries Press), 3.

5 Osborn, From the Greeks (1924), 10-11.

6 Osborn, From the Greeks (1924), 11.

7 James Rachels, Created From Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 10.

8 Charles Darwin, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, ed. Nora Barlow (London: Collins, 1958), 92-93.

9 John Dewey, The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy, and Other Essays on Contemporary Thought (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1910), p. 11.

10 Some of the contemporary academics and researchers embracing this position include Dr. Mike Behe of Lehigh University, Dr. Walter Bradley of Texas A & M, Dr. Sigrid Hartwig-Scherer of Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich, Phillip Johnson and Dr. Jonathan Wells of the University of California at Berkeley, Dr. Robert Kaita of Princeton, Dr. Steven Meyer of Whitworth, Dr. Heinz Oberhummer of Vienna University, Dr. Siegfried Scherer of the Technical University of Munich, Dr. Jeff Schloss of Westmont, etc. There are numerous others that, to varying degrees, embrace the anthropic position, including Dr. Brandon Carter of Cambridge, Dr. Frank Tipler of Tulane, Dr. Peter Berticci of Michigan State, Dr. George Gale of University of Missouri Kansas City, Dr. John Barrow of Sussux University, Dr. John Leslie of the University of Guelph, Dr. Heinz Pagels of Rockefeller University, Dr. John Earman of University of Pittsburgh, and many others.

11 Rachels, Created From Animals (1990), 3.

12 Rachels, Created From Animals (1990),57-58.

13 Scopes v. State, 289 S. W. 363 (1927).

14 The World’s Most Famous Court Trial: Tennessee Evolution Case; A Word for Word Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-Evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925 . . . (Cincinnati: National Book Company, 1925), 83-84, Clarence Darrow, July 13, 1925.

15 The World’s Most Famous Court Trial (1925), 113, Dudley Malone, July 15, 1925.

16 See Osborn, From the Greek (1924); Peter J. Bowler, Evolution: The History of an Idea (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984); Edward Clodd, Pioneers of Evolution From Thales to Huxley (New York: Books for Libraries Press); Robert Clark, Darwin: Before and After, and Examination and Assessment (London: The Paternoster Press, 1958),

17 Thomas Paine, Life and Writings of Thomas Paine, ed. Daniel Edwin Wheeler (New York: Printed by Vincent Parke and Company, 1908), 7:2-8, “The Existence of God,” A Discourse at the Society of Theophilanthropists, Paris.

18 Paine, Life and Writings, ed. Wheeler (1908), 6:132, from his “Age of Reason Part Second,” January 27, 1794.

19 John Quincy Adams, Letters of John Quincy Adams to His Son on the Bible and Its Teachings (Auburn: James M. Alden, 1850), Letter II, 23-24.

20 Adams, Letters of John Quincy Adams (1850), Letter II, 27-28.

21 Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Jared Sparks (Boston: Tappan, Whittemore, and Mason, 1836), II:526, “A Lecture on the Providence of God in the Government of the World.”

22 Franklin, Works, ed. Jared Sparks (1836), II:526-527, “A Lecture on the Providence of God in the Government of the World.”

23 John Adams, The Adams-Jefferson Letters, ed. Lester Cappon (North Carolina: University of North Carolina, 1959) 374-375, to Thomas Jefferson, September 14, 1813.

24 James Wilson, The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, ed. Bird Wilson (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), I:113-114.

25 From Daniel Webster’s 1801 Senior Oration at Dartmouth, translated from the Latin by John Andrew Murray, received by the author from the translator on February 21, 2008. The oration is titled “On the Goodness of God as manifested in His work, 1801.”

26 Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb (Washington, D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), XV:426-427, letter to John Adams, April 11, 1823.