(There is an outline and a select dictionary at the end of this Address.)

Friends and Fellow-Citizens:

The period for a new election of a citizen, to administer the Executive Government of the United States being not far distant, and the time actually arrived, when your thoughts must be employed in designating the person, who is to be clothed with that important trust, it appears to me proper, especially as it may conduce to a more distinct expression of the public voice, that I should now apprise you of the resolution I have formed to decline being considered among the number of those out of whom a choice is to be made.

I beg you at the same time to do me the justice to be assured, that this resolution has not been taken, without a strict regard to all the considerations appertaining to the relation which binds a dutiful citizen to his country; and that in withdrawing the tender of service, which silence in my situation might imply, I am influenced by no diminution of zeal for your future interest, no deficiency of grateful respect for your past kindness, but am supported by a full conviction that the step is compatible with both.

The acceptance of, and continuance hitherto in the office to which your suffrages have twice called me have been a uniform sacrifice of inclination to the opinion of duty and to a deference for what appeared to be your desire. I constantly hoped that it would have been much earlier in my power, consistently with motives which I was not at liberty to disregard, to return to that retirement from which I had been reluctantly drawn. The strength of my inclination to do this previous to the last election had even led to the preparation of an address to declare it to you; but mature reflection on the then perplexed and critical posture of our affairs with foreign nations, and the unanimous advice of persons entitled to my confidence impelled me to abandon the idea. I rejoice, that the state of your concerns, external as well

as internal, no longer renders the pursuit of inclination incompatible with the sentiment of duty, or propriety, and am persuaded, whatever partiality may be

retained for my services, that in the present circumstances of our country, you will not disapprove my determination to retire.

The impressions with which I first undertook the arduous trust were explained on the proper occasion. In the discharge of this trust, I will only say that I have, with good intentions, contributed towards the organization and administration of the government the best exertions of which a very fallible judgment was capable. Not unconscious in the outset of the inferiority of my qualifications, experience in my own eyes, perhaps still more in the eyes of others, has strengthened the motives to diffidence of myself; and every day the increasing weight of years admonishes me more and more that the shade of retirement is as necessary to me as it will be welcome. Satisfied that if any circumstances have given peculiar value to my services they were temporary, I have the consolation to believe that, while choice and prudence invite me to quit the political scene, patriotism does not forbid it.

In looking forward to the moment which is intended to terminate the career of my public life my feelings do not permit me to suspend the deep acknowledgment of that debt of gratitude, which I owe to my beloved country for the many honors it has conferred upon me; still more for the steadfast confidence with which it has supported me, and for the opportunities I have thence enjoyed of manifesting my inviolable attachment by services faithful and persevering, though in usefulness unequal to my zeal. If benefits have resulted to our country from these services, let it always be remembered to your praise and as an instructive example in our annals, that under circumstances in which the passions, agitated in every direction, were liable to mislead; amidst appearances sometimes dubious; vicissitudes of fortune often discouraging; in situations in which not unfrequently want of success has countenanced the spirit of criticism, the constancy of your support was the essential prop of the efforts and a guarantee of the plans by which they were effected. Profoundly penetrated with this idea, I shall carry it with me to my grave as a

strong incitement to unceasing vows that Heaven may continue to you the choicest tokens of its beneficence that your union and brotherly affection may be perpetual; that the free Constitution which is the work of your hands may be sacredly maintained; that its administration in every department may be stamped with wisdom and virtue; that, in fine, the happiness of the people of these States, under the auspices of liberty, may be made complete by so careful a preservation and so prudent a use of this blessing as will acquire to them the glory of recommending it to the applause, the affection, and adoption of every nation which is yet a stranger to it.

Here, perhaps, I ought to stop. But a solicitude for your welfare which cannot end but with my life, and the apprehension of danger natural to that solicitude, urge me on an occasion like the present to offer to your solemn contemplation and to recommend to your frequent review some sentiments which are the result of much reflection, of no inconsiderable observation, and which appear to me all important to the permanency of your felicity as a people. These will be offered to you with the more freedom as you can only see in them the disinterested warnings of a parting friend, who can possibly have no personal motive to bias his counsel. Nor can I forget as an encouragement to it your indulgent reception of my sentiments on a former and not dissimilar occasion.

Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the attachment.

The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so, for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquillity at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that from different causes and from different quarters much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth, as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment, that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual

happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned, and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

For this you have every inducement of sympathy and interest. Citizens by birth or choice of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together. The independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts, of common dangers, sufferings, and successes.

But these considerations, however powerfully they address themselves to your sensibility, are greatly outweighed by those which apply more immediately to your interest. Here every portion of our country finds the most commanding motives for carefully guarding and preserving the union of the whole.

The North, in an unrestrained intercourse with the South, protected by the equal laws of a common government, finds in the productions of the latter great additional resources of maritime and commercial enterprise and precious materials of manufacturing industry. The South, in the same intercourse, benefiting by the same agency of the North, sees its agriculture grow and its commerce expand. Turning partly into its own channels the seamen of the North, it finds its particular navigation invigorated; and while it contributes in different ways to nourish and increase the general mass of the national navigation, it looks forward to the protection of a maritime strength to which itself is unequally adapted. The East, in a like intercourse with the West, already finds, and in the progressive improvement of interior communications by land and water will more and more find, a valuable vent for the commodities which it brings from abroad or manufactures at home. The West derives from the East supplies requisite to its growth and comfort, and what is perhaps of still greater consequence, it must of necessity owe the secure enjoyment of indispensable outlets for its own productions to the weight, influence, and the future maritime strength of the Atlantic side of the Union, directed by an indissoluble community of interest as one nation. Any other tenure by which the West can hold this essential advantage, whether derived from its own separate strength, or from an apostate and unnatural connection with any foreign power, must be intrinsically precarious.

While, then, every part of our country thus feels an immediate and particular interest in union, all the parts combined in the united mass of means and efforts cannot fail to find greater strength, greater resource, proportionately greater security from external danger, a less frequent interruption of their peace by foreign nations, and what is of inestimable value, they must derive from Union an exemption from those broils and wars between themselves which so frequently afflict neighboring countries not tied together by the same governments, which their own rivalries alone would be sufficient to produce, but which opposite foreign alliances, attachments, and intrigues would stimulate and embitter. Hence, likewise, they will avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty. In this sense it is, that your union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty, and that the love of the one ought to endear to you the preservation of the other.

These considerations speak a persuasive language to every reflecting and virtuous mind, and exhibit the continuance of the union as a primary object of patriotic desire. Is there a doubt whether a common government can embrace so large a sphere? Let experience solve it. To listen to mere speculation in such a case were criminal. We are authorized to hope that a proper organization of the whole, with the auxiliary agency of governments for the respective subdivisions, will afford a happy issue to the experiment. It is well worth a fair and full experiment. With such powerful and obvious motives to union affecting all parts of our country, while experience shall not have demonstrated its impracticability, there will always be reason to distrust the patriotism of those who in any quarter may endeavour to weaken its bands.

In contemplating the causes which may disturb our union it occurs as matter of serious concern that any ground should have been furnished for characterizing parties by geographical discriminations Northern and Southern, Atlantic and Western whence designing men may endeavor to excite a belief that there is a real difference of local interests and views. One of the expedients of party to acquire influence within particular districts is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heart burnings which spring from these misrepresentations; they tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection. The inhabitants of our Western country have lately had a useful lesson on this head. They have seen in the negotiation by the Executive and in the unanimous ratification by the Senate of the treaty with Spain, and in the universal satisfaction at that event

throughout the United States, a decisive proof how unfounded were the suspicions propagated among them of a policy in the General Government and in the Atlantic States unfriendly to their interests in regard to the Mississippi. They have been witnesses to the formation of two treaties – that with Great Britain and that with Spain – which secure to them everything they could desire in respect to our foreign relations towards confirming their prosperity. Will it not be their wisdom to rely for the preservation of these advantages on the union by which they were procured? Will they not henceforth be deaf to those advisers, if such there are, who would sever them from their brethren and connect them with aliens?

To the efficacy and permanency of your union a government for the whole is indispensable. No alliances, however strict, between the parts can be an adequate substitute. They must inevitably experience the infractions and interruptions which all alliances in all times have experienced. Sensible of this momentous truth, you have improved upon your first essay by the adoption of a Constitution of Government better calculated than your former for an intimate union and for the efficacious management of your common concerns. This Government, the offspring of our own choice, uninfluenced and unawed, adopted upon full investigation and mature deliberation, completely free in its principles, in the distribution of its powers, uniting security with energy, and containing within itself a provision for its own amendment, has a just claim to your confidence and your support. Respect for its authority, compliance with its laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true liberty. The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government. But the constitution which at any time exists till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole people is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very

idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government.

All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction; to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community, and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans, digested by common councils and modified by mutual interests.

However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely in the course of time and things to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people, and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

Toward the preservation of your Government and the permanency of your present happy state, it is requisite not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority, but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles, however specious the pretexts. One method of assault may be to effect in the forms of the Constitution alterations which will impair the energy of the system, and thus to undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In all the changes to which you may be invited remember that time and habit are at least as necessary to fix the true character of governments as of other human institutions; that experience is the surest standard by which to test the real tendency of the existing constitution of a country; that facility in changes upon the credit of mere hypothesis and opinion exposes to perpetual change, from the endless variety of hypothesis and opinion; and remember especially that for the efficient

management of your common interests in a country so extensive as ours a Government of as much vigor as is consistent with the perfect security of liberty is indispensable. Liberty itself will find in such a government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest Guardian. It is, indeed, little else than a name where the Government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.

I have already intimated to you the danger of parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on geographical discriminations. Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally.

This Spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but in those of the popular form it is seen in its greatest rankness and is truly their worst enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual, and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the public councils, and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another; foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passion. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of the government, and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true and in governments of a monarchical cast patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose; and there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.

It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration to confine themselves within their respective constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism. A just estimate of that love of power and proneness to abuse it which predominates in the human heart is sufficient to satisfy us of the truth of this position. The necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power, by dividing and distributing it into different depositories, and constituting each the guardian of the public weal against invasions by the others, has been evinced by experiments ancient and modern, some of them in our country and under our own eyes. To preserve them must be as necessary as to institute them. If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this in one instance may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit which the use can at any time yield.

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness – these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked, “where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice?” And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

It is substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule indeed extends with more or less force to every species of free government. Who that is a sincere friend to it can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric?

Promote, then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible, avoiding occasions of expense by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it; avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertions in times of peace to discharge the debts which unavoidable wars have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear. The execution of these maxims belongs to your representatives; but it is necessary that public opinion should cooperate. To facilitate to them the performance of their duty it is essential that you should practically bear in mind that towards the payment of debts there must be revenue; that to have revenue there must be taxes; that no taxes can be devised which are not more or less inconvenient and unpleasant; that the intrinsic embarrassment inseparable from the selection of the proper objects (which is always a choice of difficulties), ought to be a decisive motive for a candid construction of the conduct of the Government in making it, and for a spirit of acquiescence in the measures for obtaining revenue which the public exigencies may at any time dictate.

Observe good faith and justice towards all nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all. Religion and morality enjoin this conduct. And can it be that good policy does not equally enjoin it? It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and at no distant period a great nation to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence. Who can doubt that in the course of time and things the fruits of such a plan would richly repay any temporary advantages which might be lost by a steady adherence to it? Can it be that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a nation with its virtue? The experiment, at least, is recommended by every sentiment which ennobles human nature. Alas! is it rendered impossible by its vices?

In the execution of such a plan nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded, and that in place of them just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The nation which indulges towards another an habitual hatred or an habitual fondness is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. Antipathy in one nation against another disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur. Hence frequent collisions, obstinate, envenomed, and bloody contests. The nation prompted by ill-will and resentment sometimes impels to war the government contrary to the best calculations of policy. The government sometimes participates in the national propensity, and adopts through passion what reason would reject. At other times it makes the animosity of the nation subservient to projects of hostility,

instigated by pride, ambition, and other sinister and pernicious motives. The peace often, sometimes perhaps the liberty, of nations has been the victim.

So, likewise, a passionate attachment of one nation for another produces a variety of evils. Sympathy for the favorite nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter without adequate inducement or justification. It leads also to concessions to the favorite nation of privileges denied to others, which is apt doubly to injure the nation making the concessions by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained, and by exciting jealousy, ill-will, and a disposition to retaliate in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld; and it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favorite nation) facility to betray or sacrifice the interests of their own country without odium, sometimes even with popularity, gilding with the appearances of a virtuous sense of obligation, a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption, or infatuation.

As avenues to foreign influence in innumerable ways, such attachments are particularly alarming to the truly enlightened and independent patriot. How many opportunities do they afford to tamper with domestic factions, to practise the arts of seduction, to mislead public opinion, to influence or awe the public councils! Such an attachment of a small or weak toward a great and powerful nation dooms the former to be the satellite of the latter. Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow-citizens), the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government. But that jealousy, to be useful, must be impartial, else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defense against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots who may resist the intrigues of the favorite are

liable to become suspected and odious, while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is, in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.

Europe has a set of primary interests which to us have none or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.

Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one people, under an efficient government, the period is not far off when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by our justice, shall counsel.

Why forgo the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor, or caprice?

It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world, so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it; for let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing engagements. I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs that honesty is always the best policy. I repeat, therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But in my opinion it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Taking care always to keep ourselves by suitable establishments on a respectable defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.

Harmony, liberal intercourse with all nations are recommended by policy, humanity, and interest. But even our commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand, neither seeking nor granting exclusive favors or preferences; consulting the natural course of things; diffusing and diversifying by gentle means the streams of commerce, but forcing nothing; establishing with powers so disposed, in order to give trade a stable course, to define the rights of our merchants, and to enable the Government to support them, conventional rules of intercourse, the best that present circumstances and mutual opinion will permit, but temporary and liable to be from time to time abandoned or varied as experience and circumstances shall dictate; constantly keeping in view that it is folly in one nation to look for disinterested favors from another; that it must pay with a portion of its independence for whatever it may accept under that character; that by such acceptance it may place itself in the condition of having given equivalents for nominal favors, and yet of being reproached with ingratitude for not giving more. There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favors from nation to nation. It is an illusion which experience must cure, which a just pride ought to discard.

In offering to you, my countrymen, these counsels of an old and affectionate friend I dare not hope they will make the strong and lasting impression I could wish – that they will control the usual current of the passions or prevent our nation from running the course which has hitherto marked the destiny of nations. But if I may even flatter myself that they may be productive of some partial benefit, some occasional good – that they may now and then recur to moderate the fury of party spirit, to warn against the mischiefs of foreign intrigue, to guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism – this hope will be a full recompense for the solicitude for your welfare by which they have been dictated.

How far in the discharge of my official duties I have been guided by the principles which have been delineated the public records and other evidences of my conduct must witness to you and to the world. To myself, the assurance of my own conscience is that I have at least believed myself to be guided by them.

In relation to the still subsisting war in Europe my proclamation of the 22d of April, 1793, is the index to my plan. Sanctioned by your approving voice and by that of your representatives in both Houses of Congress, the spirit of that measure has continually governed me, uninfluenced by any attempts to deter or divert me from it.

After deliberate examination, with the aid of the best lights I could obtain, I was well satisfied that our country, under all the circumstances of the case, had a right to take, and was bound in duty and interest to take, a neutral position. Having taken it, I determined as far as should depend upon me to maintain it with moderation, perseverance, and firmness.

The considerations which respect the right to hold this conduct it is not necessary on this occasion to detail. I will only observe, that, according to my understanding of the matter, that right, so far from being denied by any of the belligerent powers, has been virtually admitted by all.

The duty of holding a neutral conduct may be inferred, without any thing more, from the obligation which justice and humanity impose on every nation, in cases in which it is free to act, to maintain inviolate the relations of peace and amity towards other nations.

The inducements of interest for observing that conduct will best be referred to your own reflections and experience. With me a predominant motive has been to endeavor to gain time to our country to settle and mature its yet recent institutions, and to progress without interruption to that degree of strength and consistency which is necessary to give it, humanly speaking, the command of its own fortunes.

Though, in reviewing the incidents of my Administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope that my country will never cease to view them with indulgence, and that, after forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.

Relying on its kindness in this as in other things, and actuated by that fervent love toward it which is so natural to a man who views in it the native soil of himself and his progenitors for several generations, I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I promise myself to realize without alloy the sweet enjoyment of partaking in the midst of my fellow citizens the benign influence of good laws under a free government – the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers.

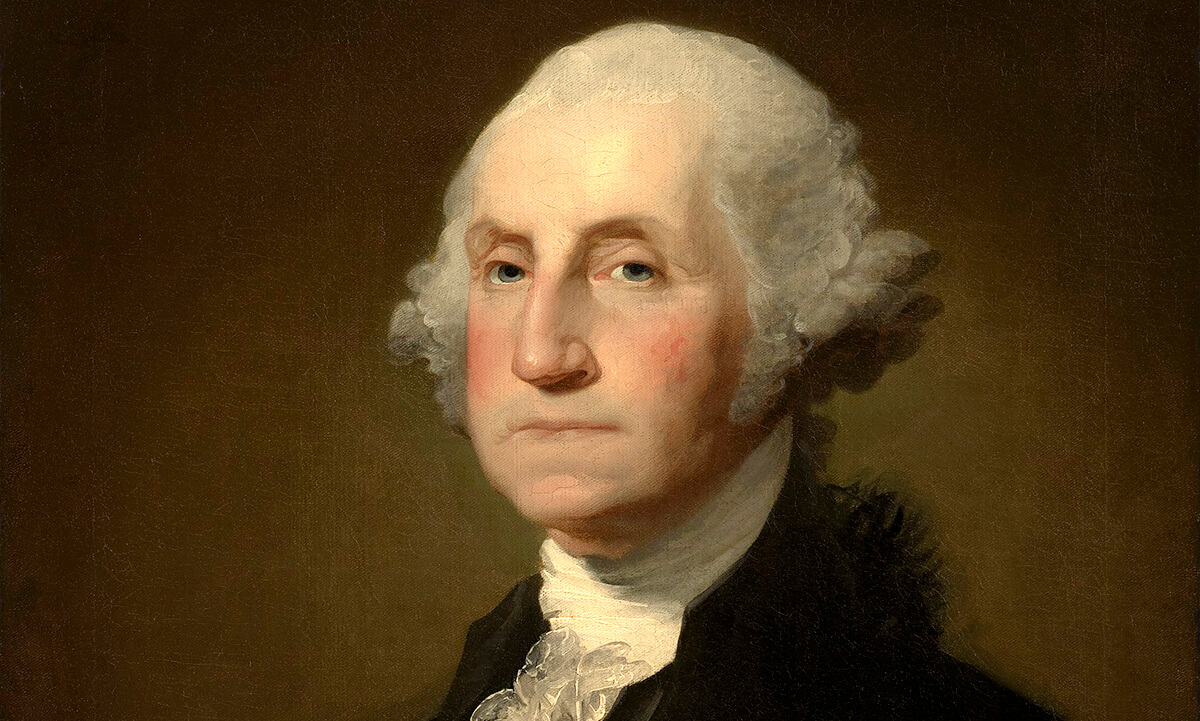

George Washington

OUTLINE

- Retirement from office.

- He realizes people must be thinking about his replacement, therefore he declines re-election.

- He has thought it through, and feels like it is in everyone’s best interest.

- He wanted to retire earlier, but foreign affairs and advice from those he respected caused him to “abandon the idea.”

- Now that everything is calm, he is persuaded that the people will not disapprove of this “determination to retire.”

- He is convinced his age forces retirement, and he welcomes the opportunity.

- He offers gratitude for the people’s support.

- He offers a blessing “that Heaven may continue to you the choicest tokens of its beneficence. . .”

- Scope of the Address.

- His sentiments are for the people’s “frequent review,” he wanted us to read and re-read the Address.

- His only motive was as a friend.

- He felt no need to recommend a love of liberty – it was already there.

- Unity of Government.

- Unity is a “main pillar” of “real independence”:

- for the support of “tranquility at home”

- for “your peace abroad”

- for “your safety”

- for “your prosperity”

- for “that very liberty which you so highly prize.”

- Common attributes of unity:

- same religion

- manners

- habits

- political principles.

- The most commanding motive is to preserve the “union of the whole.”

- The North, South, East, and West all depend on each other.

- Unity leads to greater strength, resources, and security.

- Unity will help “avoid the necessity of . . . overgrown military establishments” and will be the main “prop of your liberty.”

- He questions the patriotism of anyone who tries to “weaken its bands.”

- It was unity that brought two valuable treaties:

- with Great Britain

- with Spain.

- Government for the whole – via the Constitution – is indispensable; not just alliances between sections.

- the adoption of the Constitution was an improvement on the former “essay.”

- respect for its authority, compliance with its laws, and acquiescence in its measures are fundamental maxims of true liberty.

- the people’s right to alter constitutions is the basis of our political system.

- Spirit of Party.

- Parties are “potent engines” that men will use to take over the “reins of government.”

- Washington warns against parties’ “baneful effects”:

- leads to the absolute power of an individual

- “discourage and restrain” the spirit of party

- leads to “jealousies and false alarms”

- “animosity of one part against another”

- can lead to “riot and insurrection”

- opens “door to foreign influence and corruption”

- “it is a spirit not to be encouraged.”

- Spirit of Encroachment.

- Leads to “a real despotism.”

- There is a necessity of “reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power.”

- If a problem arises, correct it by an amendment, not by “usurpation.”

- Religion and Morality.

- Are “indispensable supports” for “political prosperity.”

- Are the “firmest props of the duties of Men and Country.”

- The oaths in our courts would be useless without “the sense of religious obligation.”

- “And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion.”

- “Reason and experience both forbid us to expect, that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

- “Promote, then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge.”

- Debt.

- “Avoid occasions of expense by cultivating peace . . . .”

- “Timely disbursements to prepare for danger” are better than “greater disbursements to repel it.”

- Avoid debt: in time of peace, pay off debts..

- Public opinion should “cooperate” with their representatives to pay off debt.

- Some taxes are necessary even though “inconvenient and unpleasant.”

- Foreign Policy.

- We should exercise “good faith and justice towards all nations.”

- “religion and morality enjoin this conduct”

- we should be guided by “an exalted justice and benevolence.”

- Replace “inveterate antipathies” (hatred) and passionate attachments with “just and amicable feelings.”

- “passionate attachments” produce a variety of evils

- these attachments will lead you into “quarrels and wars”

- they will also lead to favoritism, conceding “privileges denied to others.”

- Foreign “attachments” are “alarming” because they open the door to foreigners who might:

- “tamper with domestic factions”

- “practise the arts of seduction”

- “mislead public opinion”

- influence “Public Councils.”

- “Foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of Republican Government.”

- “The great rule of conduct for us”: “as little political connection as possible.”

- we should fulfill obligations, then stop

- we should not get involved in Europe’s affairs.

- Our “detached and distant situation . . . enables . . . a different course.”

- “Steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.”

- However, we may have “temporary alliances, for extraordinary emergencies.”

- Maintain “a liberal intercourse with all nations.”

- Conclusion.

- Washington hopes his counsel will:

- “help moderate the fury of party spirit”

- “warn against the mischiefs of foreign intrigue”

- “guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism.”

- He believes himself to be guided by the “principles which have been delineated” above.

- A “neutral position” is the best course to take regarding the “subsisting war in Europe.”

- that neutrality is the right course has been “admitted by all.”

- our “motive has been to endeavor to gain time for our country to settle and mature” until America has “command of its own fortunes.”

- Washington asks “the Almighty” to correct any unintentional errors or defects from his administration.

- He looks forward to retiring and enjoying “good laws under a free government.”

- Closing words.

VOCABULARYacquiescence – agreement without protest. Consent.

actuate – put into motion. Motivate.

admonish – to counsel against. Caution.

alienate – to cause to become unfriendly. Exclude.

alliance – a formal pact between nations. Partnership.

animosity – bitter hostility. Hatred.

antipathies – strong feelings of hatred or opposition. Aversions.

apostate – abandoning one’s principles. Defective or Traitorous.

appellation – a name or title.

appertaining – relating to.

apprise – to give notice; to inform. Notify.

arduous – demanding great care, effort, or labor. Difficult.

artifices – subtle but base deceptions. Tricks.

assuage – make less burdensome or painful. Relieve.

auspice – protection or support. Authority.

auxiliary – giving assistance or support. Supplementary.

avert – to turn away. Prevent.

baneful – causing death, destruction, or ruin. Harmful.

belligerent – inclined or eager to fight. Hostile.

beneficence – a charitable act or gift. Kindness.

benevolence – an inclination to do kind or charitable acts. Goodness.

benign – tending to promote well-being. Beneficial.

beseech – to call upon earnestly. Request.

bias – to cause to have a prejudice view. Distort.

conceded – acknowledged as true, just, or proper. Given.

conjure – to call upon or entreat solemnly. Call upon.

consigned – turned over to another’s charge. Delivered.

consolation – the comforting in time of grief, defeat, or trouble. Comfort.

contemplation – thoughtful observation. Meditation.

countenanced – to give or express approval to. Approved.

covertly – concealed, hidden, or secret.

cultivate – promote the growth of. Develop.

deference – yielding to the wishes of another. Consideration.

deliberate – planned in advance. Intentional.

delineated – depicted in words or gestures. Outlined.

despotisms – political system with one man in absolute power. Oppression.

diffidence – the quality of lacking self-confidence. Humility.

diffusing – causing to spread freely. Spreading.

diffusion – the process of diffusing. Spreading.

diminution – reduction. Decrease.

disbursements – money paid out. Expenditures.

discriminations – acts based on prejudice. Prejudices.

dispositions – an habitual tendency or inclination. Tendencies.

diversifying – giving variety to. Varying.

dubious – causing doubt or uncertainty. Uncertain.

edifice – a building of imposing appearance or size. Structure.

efficacy – power to produce a desired effect. Effectiveness.

encroach – to advance beyond proper limits. Intrude.

enmities – deep-seated mutual hatred. Hostilities.

ennobles – raises in rank. Elevates.

envenomed – poisoned or embittered. Poisoned.

evinced – to show clearly or convincingly. Demonstrated.

exemption – a freedom from obligation or duty. Freedom.

exigencies – situations needing immediate attention. Necessities.

expedients – something adopted to meet an urgent need. Schemes.

facilitating – making something easier. Assisting.

fallible – capable of making an error. Imperfect.

felicity – great happiness or bliss. Happiness.

fervently – having great emotion or warmth. Earnestly.

hypothesis – something considered to be true. Assumption.

impostures – deceptions through false identities. Deceptions.

inauspicious – unfavorable.

incongruous – not consistent with what is logical, customary, or correct.

Disagreeable.

indispensable – not able to be done away with. Essential.

indissoluble – impossible to break or undo. Indestructible.

inducement – something that leads to action. Influence.

indulgent – granted as a favor or privilege. Agreeable.

inferred – figured out from evidence. Understood.

infidelity – lack of loyalty. disloyalty.

insidiously – spreading harm in a subtle way. Dishonestly.

instigated – stirred up or urged on. Aroused.

intercourse – communication between persons or groups. Business.

intimated – to announce or proclaim. Spoken.

intractable – hard to manage or govern. Stubborn.

intrigue – secret schemes or plots. Affairs.

intrinsic – having to do with the very nature of a thing. Natural.

inveterate – firmly established and deeply rooted. Established.

inviolate – not violated or changed. Unchanged.

invigorated – given strength and vitality. Energized.

inviolable – not able to be violated. Unchanging.

laudable – deserving approval. Praiseworthy.

magnanimous – noble of mind and heart. Idealistic.

maxim – fundamental principle or rule of conduct. Principle.

mitigate – to make less severe or intense. Weaken.

monarchy – a state ruled by an absolute ruler, such as a king or emperor.

obligatory – legally or morally binding. Required.

oblivion – the condition of being completely forgotten. Nonexistence.

obstinate – hard to manage, control, or subdue. Uncontrollable.

odium – a strong dislike for something. Disfavor.

pernicious – causing great harm and destruction. Destructive.

perpetrated – to be guilty of bringing something about. Committed.

perpetual – lasting for eternity. Unending.

plausible – appearing to be valid, likely, or acceptable. Believable.

posterity – future generations.

precarious – lacking in security and stability. Uncertain.

precedent – an act used as an example in future situations.

predominant – having great importance, influence, or authority. Important.

procured – obtained or acquired.

progenitors – a direct ancestor. Ancestors.

propensity – a tendency to do something. Tendency.

propagated – cause to multiply. Spread.

provocation – a reason to take action.

prudence – good judgment and common sense. Wisdom.

recompense – payment for something done. Repayment.

requisite – essential or required.

scrupulously – to do something with ethical considerations. Conscientiously.

seduction – the act of leading away from proper conduct. Misleading.

solicitude – the state of being concerned or eager. Concern.

specious – appearing to be true, but being false. Deceptive.

subservient – under the control of something. Subject.

subvert – to undermine the character, morals, or allegiance of. Overthrow.

suffrages – votes.

supposition – the idea that something is true. Idea.

tenure – the terms under which something is held. Terms.

tranquility – the state of being free from disturbance. Peace.

transient – passing away with time. Temporary.

umbrage – offense. Resentment.

usurpation – the seizing of power by force and without legal right. Overthrow.

vicissitudes – changes or variations. Changes.

vigilance – alert watchfulness. Watchfulness.

virtuous – morally excellent and righteous. Pure.

weal – the welfare of the community. Welfare.

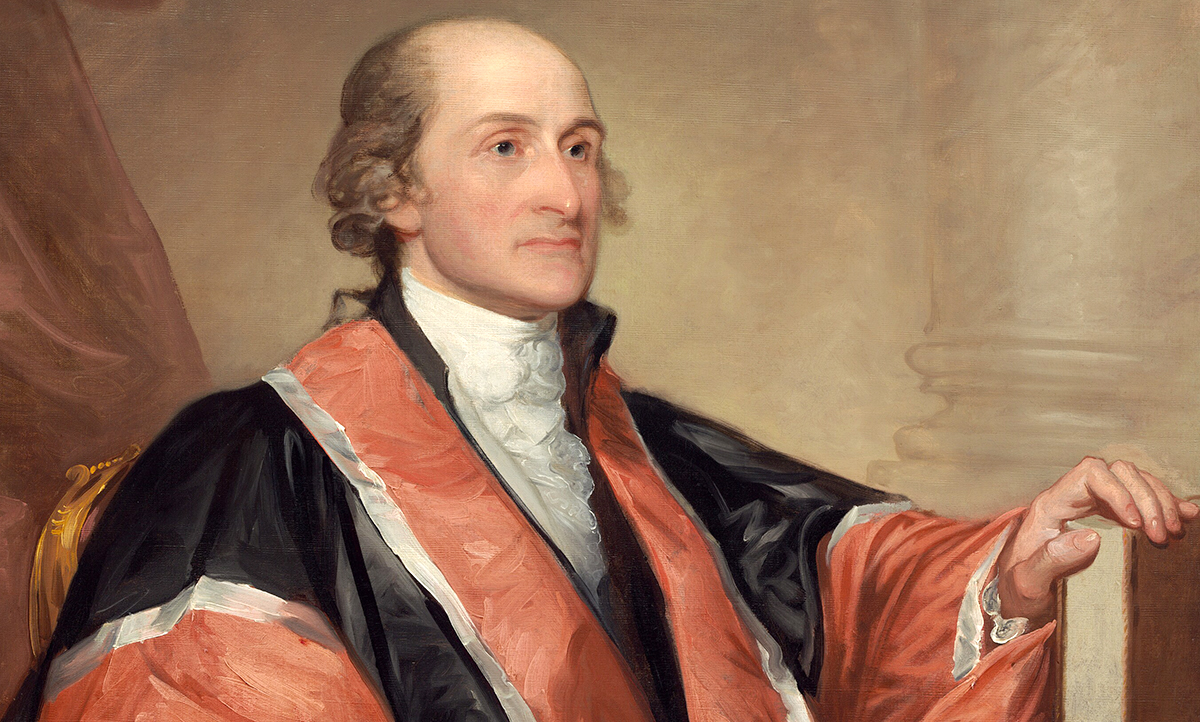

Founding Father John Jay (1745-1829) was appointed by President George Washington as the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. In addition to serving on the Supreme Court, Jay had a very distinguished history of public service. He was a member of the Continental Congress (1774-76, 1778-79) and served as President of Congress (1778-79). He helped write the New York State constitution (1777) and authored the first manual on military discipline (1777). Jay served as Chief-Justice of New York Supreme Court (1777-78) and was minister to Spain (1779). He signed the final

Founding Father John Jay (1745-1829) was appointed by President George Washington as the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. In addition to serving on the Supreme Court, Jay had a very distinguished history of public service. He was a member of the Continental Congress (1774-76, 1778-79) and served as President of Congress (1778-79). He helped write the New York State constitution (1777) and authored the first manual on military discipline (1777). Jay served as Chief-Justice of New York Supreme Court (1777-78) and was minister to Spain (1779). He signed the final