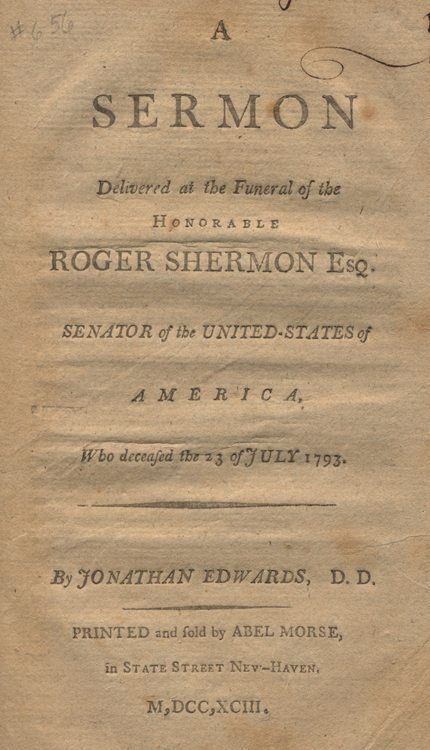

Jonathan Edwards (1745-1801) was a son of the First Great Awakening preacher, the senior Jonathan Edwards. He graduated from the College of New Jersey (1765), and was a tutor at Princeton (1767-1769). He also was pastor of: the society at White Haven, CT (1769-1795), and a Church at Colebrook, CT (1796-1799). This sermon by Edwards was preached at the funeral of Roger Sherman.

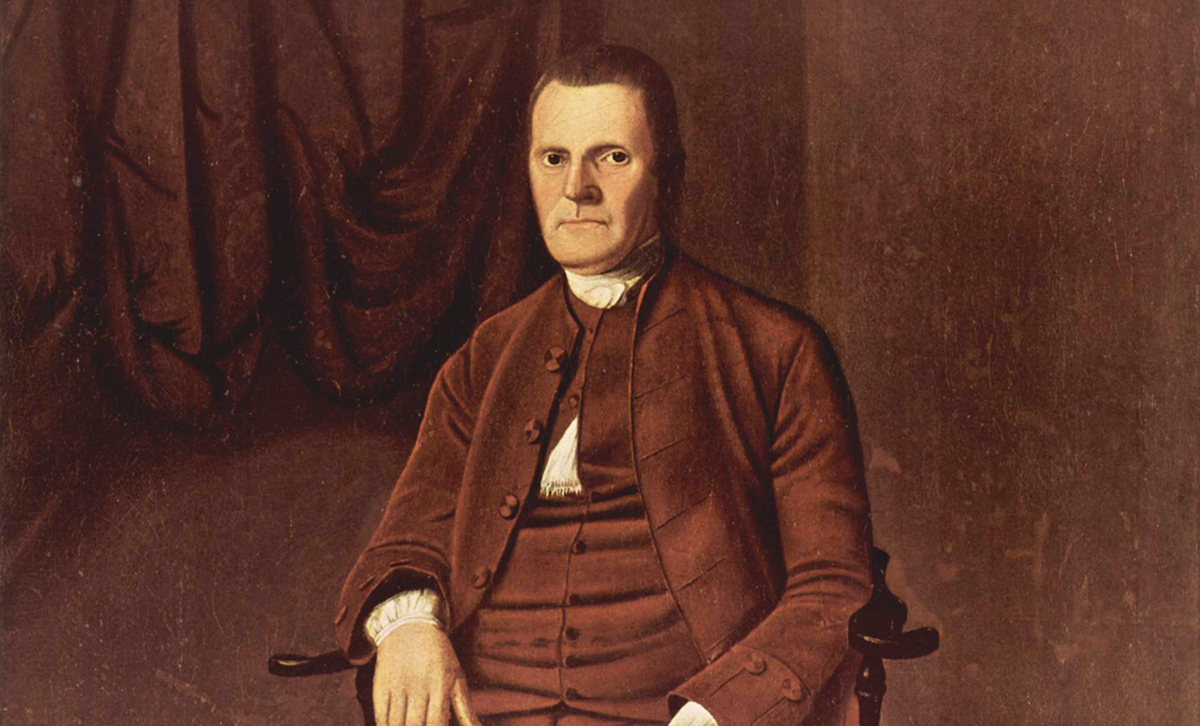

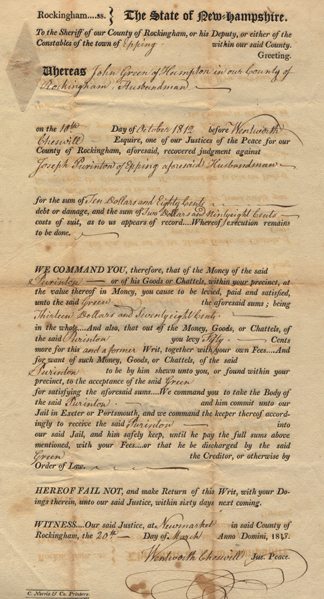

Roger Sherman (1721-1793) served in many public offices including: Justice of the Peace (1765-1766), state senator (1766-1785), a member of the Continental Congress (1774-1781, 1784), mayor of New Haven (1784-1793), delegate to the Constitutional Convention (1787), U.S. Representative (1789-1791), and U.S. Senator (1791-1793). Sherman is known for signing the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution.

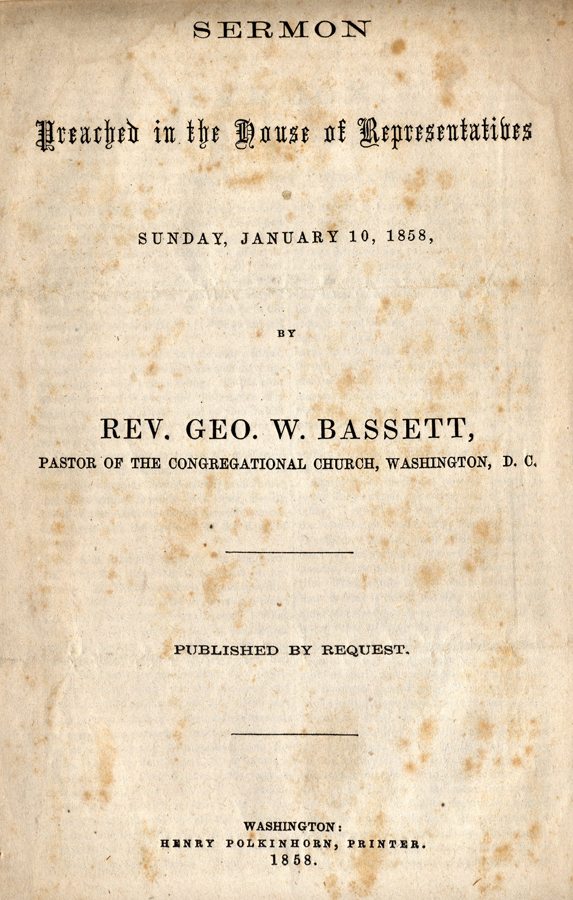

SERMON

Delivered at the Funeral of the

HONORABLE

ROGER SHERMON ESQ.

SENATOR of the UNITED STATES of

AMERICA

Who deceased the 23 of JULY 1793.

By JONATHAN EDWARDS, D. D.

Psalm, XLVI. I. God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.

Man is always dependant and therefore always wants help and strength. But he especially wants these in a time of trouble. A time of trouble is often, if not always a time of danger: and in danger we want a refuge, a place to which we may flee and be safe. Even in prosperity we are dependant, and want help, strength and refuge; but at such a time we are not apt to be so sensible of our wants. In trouble a sense of them is wont to be lively and strong and to carry full conviction to the mind. Now our text informs us where we may obtain that strength and help, and where we may find that refuge which are so necessary in trouble. God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.

As our text plainly implies, that we are liable to trouble, therefore I shall

1. Mention some of the troubles to which we are most liable.

2. Consider in what respects God is our refuge and strength.

3. Show that he is a very present help in trouble.

I. I am to mention some of the troubles to which mankind are most liable

There are several kinds.

1. We are Liable to personal troubles such as pain, sickness and death. By one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin, and so death passed upon all men, for that all have sinned. And with death came all that train of evils which attend it and lead to it. We are liable to disappointments in our expectation; to disappointment in business; to losses of property; and to poverty with all its attendant evils. There is no dependence on any possessions in Life. The most affluent often lose their property and are reduced to the greatest want. We are liable to the loss of our reputation, and this not only in consequence of ill conduct, but by the mere malice of others. Even the holy apostles and primitive Christians could not be safe from the reproaches of their enemies. I. Cor. IV. 12, 13. Being reviled, we bless : being persecuted, we suffer it : being defamed, we entreat; we are made as the filth of the world, and are the offscouring of all things unto this day.

2. We are liable to bereavement of our friends and relatives. Our happiness in this world often very much depends on them when they are taken away, we of course lose all that happiness which we derived from them. Besides the loss of them is generally attended with a positive affliction which peculiar and pungent. To separate some of the nearest connection of life is like separating soul and body, or tearing man from himself. Yet there is no discharge in this war.

3. We are liable to public calamities, such as drought, famine, wars, internal broils and commotions. Some of those calamities are severely felt at this very time, by several of the nations of the world. But happy are we that are free from them. Another publick calamity to which we and all men are liable, is the loss of wise and faithful magistrates. And this is a very great calamity. A faithful man, who can find? When we have found him and found him in the office of a principal magistrate, we ought highly to prize him, and when he is taken from us, to consider it as a great frown of divine providence.

4. We are liable to spiritual troubles as well as temporal. As sinners, we are already the subjects of that which is the source of all other evils. And in consequence of sin and depravity in general we are liable to various temptations, temptations from our own corruptions, temptations from the world and from our grand adversary. We are liable to spiritual desertions, to the hiding of the light of God’s countenance, to the just withholding of such measures of divine grace as we need for our Christian comfort and edification; nay to the accusations of a guilty conscience, to fear of divine wrath, to spiritual darkness and even to despondency. Also we are liable to trouble which respect the church of God in general. Is there a general opposition to the cause of Christ? A general persecution? Or a perversion or rejection of this truth more or less general? These must affect every Christian and be a sore trial to him. In proportion as the cause of Christianity is promoted and prospers, every real Christian is happy; in proportion as it is opposed and obstructed, it is a trouble and an affliction to him.

These are some of the kinds of trouble both temporal and spiritual, to which we are most liable. In these we need a refuge, we need strength and help: and our text direct us where we may find them.

Therefore I am to proceed,

II. To consider in what respect God is our refuge and strength.

A refuge is a shelter from any danger or distress. A person exposed to an enemy may flee to a fortress. In this case the fortress is his refuge. Exposed to a storm he may flee to his house, and then he makes his house a refuge. Now God is a refuge or a defence to all who will flee to him, whatever their strength too. Those who are weak, need strength: those who are exposed, need a refuge. But we are both weak and exposed. As creatures we are weak originally and necessarily; and are rendered much more weak by sin and depravity. Also we are exposed to innumerable foes, and to be overwhelmed by innumerable evils. Therefore we need a refuge. But God offers himself to us both as our strength and refuge. In all our troubles and dangers we may safely apply to him, and if we apply sincerely, we shall find refuge and strength. He will protect us from all the evil which is not for our good, and will over-rule that for our good, which he permits to come upon us. He will strengthen us by his grace immediately communicated. Thus he strengthened Paul under his trials, and assured him that his grace was sufficient for him: and through Christ strengthening him he could do all things.

Beside the immediate influence of the divine grace and spirit, God is also wont to strengthen by his truth.

Here it may be proper to enquire what considerations of views of God and divine truth have a happy tendency to support and strengthen Christians under the trials of life.

I. The consideration that God reigns universally and that he orders all their afflictions, happily tends to support and strengthen them. His kingdom ruleth over all and his disposal extendeth to all events whatsoever; not only to those which we acknowledge to be important, such as the rise and fall of kingdoms and empires &c. But to those which we are apt to think are most unimportant and trifling. For the former depend on the latter. The selling of Joseph into Egypt, the consequent preservation of the family of Jacob and the fulfilment of God’s covenant with Abraham, all depended on the seemly trifling occurrences of a boy’s dream, and of his father’s making of him a coat of divers colours. And even the crucifixion of our Lord and the redemption of mankind depended on the giving of a sop to one of the disciples. Therefore there is no foundation, for the infidel objection to an universal providence, that some events are too small and trifling to be the objects of the divine attention. The scriptures assure us, that tho’ two sparrows are of such small value as to be sold for a farthing, yet not one of them falleth to the ground without our heavenly father; and that the very hairs of our heads are all numbered by him.

Some readily grant an universal divine disposal as to natural events, but deny it with respect to the free actions of moral agents, as they imagine such a disposal to be inconsistent with the freedom of those actions. If the freedom of those actions consist in contingence, or in the circumstance that they are not caused by anything external to the mind; undoubtedly a disposal of providence extending to those actions would be inconsistent with their freedom. But if the freedom of those actions consist in their voluntariness, and if a man be free to anything with respect to which he is not under either a compulsion or restraint to which his will on the whole is opposed or may be supposed to be opposed; then there is not the least inconsistence between human liberty and an universal and overruling agency of God in all events whatsoever.

As God is perfect, all his works must be perfect, and his providence is directed by perfect wisdom and goodness. Therefore all that he does, or permits to take place, is, considered as a dispensation of providence, perfectly, wise, just and good. The Judge of all the earth with and must do right. He cannot err. This under the greatest afflictions is a most strengthening and supporting consideration.

2. The consideration that God requires submission and patience under all afflictions is of the same happy tendency. As was observed under the preceding particular, the Judge of all the earth cannot do otherwise than right; therefore he requires nothing which is not right and reasonable. This requirement is not only authoritative and in that view must be complied with; but we ought to comply with it, in consideration of the reasonableness and fitness of it: so that in instances of affliction which are most dark and mysterious, we may implicitly believe that submission and acquiescence are no more than our reasonable service, since God requires them. This consideration tends to strengthen against impatience and murmuring, and against fainting in the day of adversity.

3. That all our afflictions will subserve the divine glory and the general good of the created system, is also supporting and strengthening to every pious and benevolent mind. — t

he declarative glory of God and the good of the created system mutually imply each other and are one and the same thing. When good is promoted in the creation, God is glorified; and when God is glorified, Good is promoted in the creation. But the greatest good of the created system no more implies the happiness of every individual, than the greatest good of the state implies the happiness of every citizen.

And as it was the original design of God to glorify himself and to promote the happiness of the creation, to the highest possible degree; so he hath chosen a plan or system of the univers, of all other in the best possible manner adapted to these ends. To imagine the contrary, would be an impeachment of his goodness, and would imply that he was by some principle opposed to goodness, kept back from communicating that good, which he could easily have communicated.

I know that it has been objected, that on the supposition, that God has adopted the best possible system of the universe, he hath exhausted his own infinite goodness; which it is said, is an absurdity, because infinite goodness is by the terms inexhaustible. — But is infinite goodness any more inexhaustible, than any attribute of God? All his attributes are equally infinite, as his goodness; for instance his truth or his wisdom. Yet it will not be denied that he exhausts his truth in all his communications with his creatures, and speaks as truly as it is possible for him to speak; or that he exhausts his wisdom in all his conduct, and acts as wisely as it is possible he should act. Therefore there is no absurdity in supposing, that God acted as wisely as it is possible he should act, in choosing his particular system of the universe, and that he exhausted his infinite wisdom in this, but well as in every other instance of his conduct. — But how could he have acted in the wisest possible manner if he did not choose the best possible system? Does wisdom ever dictate anything inconsistent with goodness? Or are infinite wisdom and infinite goodness opposed to each other?

If the system which God hath in fact adopted the wisest and best possible doubtless every part and every event in this system is in the best manner calculated to subserve the ends of infinite wisdom and goodness. Not that all thing and events have this tendency in their own nature. No many of them have a diametrically opposite tendency. Still under the overruling hand of God they are made to subserve the best purposes.

This then is one great comfort which the Christian has under all his afflictions. Though he suffers, he suffers not in vain. His sufferings answer most important and benevolent purposes. God is thereby glorified and the happiness of the creation is promoted. And nothing can be more comforting and supporting than this to every benevolent soul.

4. The consideration that our afflictions will, unless we misimprove them, subserve our own personal good too, is of the same strengthening tendency. If we improve our afflictions aright, we shall be humbled under them, shall repent of our sins, which are the procuring cause of all divine chastisements, and shall give glory to God. And if we do thus, it will prove, that we are reconciled to God and are of those who love God. But we know that all things work together for good that love God. Therefore their afflictions, as they respect them personally, are not in vain. Their present light afflictions, which are but for a moment, work our for them a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory.

In this view, how can they, even from regard to their own personal interest, with their afflictions had not come upon them? Would they wish their final happiness to be diminished? Would they wish their own best interest to be in a less degree promoted?

Beside these general observations concerning all afflictions, there are particular considerations adapted to support under particular afflictions.

1. Under personal afflictions. If we be visited with sickness, God is able to heal us, and he will, if it be best; if it be most for his glory and our good. Do we meet with losses? God who gave us all we have or ever have had, has a perfect right to take it all from us, and at such time and in such manner as he pleases. And if God deprive us of temporal good things, still he has provided for us eternal good things, even durable riches and righteousness : he offers these to us, freely, without money and without price. Though we suffer shame and obloquy here, we may inherit divine honors hereafter; we may be made Kings and Priests unto God, and inherit a crown of glory which shall not fade away. Though we lose our present lives, we may secure eternal life, a life of compleat happiness and inconceivable glory.

2. Under bereavements he can more than make up the loss by his special grace. Also he can raise up other friends who shall be equally benevolent, as those whom he hath taken away. Or he can provide for us and protect us by his special providence. When father and mother forsake us, he can take us up; Psalm, xxvii. 10. He stiles himself a father of the fatherless and a judge of widows. He can take care of them in every situation in life, and provide for them in all their variety of circumstances; he can make even their losses to work together for their good : so that while they are deprived of their dearest and most important friends and relatives, they may be made rich in faith and heirs of the kingdom. Thus all their afflictions may issue in their unspeakable gain.

Such losses teach those who are the subjects of them, to trust not in the Creature, but in the Creator. They tend to draw off their affections from sublunary enjoyments and objects to shew them the vanity of all hopes from them and dependence on them ; and to excite them to seek another and a better portion. Deprive of their parent, their friend, their guardian, they have strong motives set before them to seek a better friend, a more bountiful benefactor, a more able protector, and a more excellent father.

When our friends or relatives are removed by death, it strongly reminds us of our own death. When they are gone into the eternal world, this naturally leads us to think more of that world, and to realize that we ourselves must shortly go tither, and that therefore we ought to prepare.

3. When we are under public frowns and calamities, we ought to remember, that God reigns over nations as well as over individuals; that we may as safely leave our national, as our private concerns with him; and that with respect to these and all other things we ought to make him our refuge and our strength.

4. Under spiritual troubles our obligation to have recourse to God for help is, if possible still greater, than when we are under troubles of any other kind. For our dependence on him in this case is more immediate and more manifest than in any other. Who but he can heal the broken spirit, can forgive sins, can sanctify the soul or can save from eternal perdition? And he is abundantly and infinitely able and is ready to grant these spiritual and inestimable blessings to those who truly apply to him for them.

III. It was proposed to show, that he is a very present help in trouble.

He is always immediately present with us both as to time and place. We cannot escape from his presence. He therefore is always at hand to receive our applications, to hear our prayers and to afford us help. This is certainly a very great advantage. Help at a very great distance either of time or place is not to be compared to that which is present. Before it shall arrive, we may be wholly overwhelmed and ruined.

Thus I have briefly considered the several subjects, which seemed naturally to arise from our text; I am no to apply these general observations to the present mournful occasion. The present is a time of trouble and affliction. The death of that eminent and excellent man, whose remails are now to be laid in the dust, is a source of affliction in several respects; it is so to his family, to all his friends, to the church of which he was a member, to this city, to the state and to the United States. In this death they have all sustained a loss.

That we may rightly estimate this loss, and be properly humbly under the divine chastisement, let us take a brief survey of his life and character.

He was born at Newtown in Massachusetts, April 19, 1721. He was the son of Mr. William Sherman, the son of Joseph Sherman Esq. the son of Capt. John Sherman, who came from Dedham in England to Watertown in Massachusetts, about the year 1635. He was not favored with a public education, or even with a private tutor. His superior improvements arose from his superior genius, from his thirst for knowledge and from his personal exertions and infatigable industry in the pursuit of it. 1By these he attained to a very considerable share of knowledge in general, particularly in his own native language, in logic, geography, mathematics, the general principles of philosophy, history, theology and above all in law and politics. These last were his favorite studies, and in these he excelled. If he in this manner attained to the same improvements and capacity of usefulness, to which others attain not without the greatest advantages of education, ho far would he have out stripped them, had he been favored with their advantages?

His father died when he was but nineteen years old, and from that time the care of his mother, who lived to a great age, and the education of a numerous family of brothers and sisters, were devolved on him. In this part of his life filial piety to a parent at length worn out by both as to body and mind; and fraternal affection to his brothers and sisters now in a good measure dependant on him, appeared in an unusual degree. Though cramped in his own education, he assisted by advancements of his own property, two of his brethren to a liberal education.

Before he was twenty one, he made a public profession of religion, which he adorned through life.

He came to this then Colony of Connecticut and settled at New-Milford in Jun 1743, being then twenty two years of age; and at the age of twenty eight was married to Miss Elizabeth Hartwell of Stoughton in Massachusetts, by whom he had seven children, two of whom died young at New-Milford, and two since he resided in this town. His wife died in October 1760. At New-Milford he was much respected by his fellow citizens and much employed in public business. In 1745, within two years of his removal into the Colony, and when he was of the age of twenty four, he was appointed a surveyor of lands for the county in which he resided; which is a proof of his early improvement in mathematical knowledge.

Although he was not educated a lawyer, yet by his abilities and application he had acquired such knowledge in the law, and such a reputation as a counsellor, that he was persuaded by his friends to come forward to the bar, and was accordingly admitted an attorney at law, in December 1754. The next year he was appointed a justice of the peace and was chosen by the freemen of the town to represent them in the Legislature, as he was generally thenceforward, during his continuance at New-Milford. Also he sustained the office of a deacon in the Church in that town.

He continued to practice law with reputation, till May 1759, when he was appointed a justice of the Court of common pleas for the county.

He removed to his town in the year 1761. Having lost his wife, as was before observed, he was in May 1763 married to Miss Rebecca Prescot of Danvers in Massachusetts, by whom he had eight children, seven of whom are now living.

After his removal to this town, he was made a justice of the peace for the county of New-Haven, frequently represented the town in the Legislature, and in 1765 was appointed one of the justices of the Court of common pleas for this county. He was for many years the treasurer of the College in this City, and received an honorary degree of Master of Arts.

In 1766 he was by the voice of the freemen of the Colony at large, chosen an assistant and in the same year was appointed a judge of the Superior Court. This last office he sustained for twenty three years, and the office of an Assistant for nineteen years; after which the law was enacted rendering the two offices incompatible and he chose to continue in the office of a Judge.

He was a member of the first Congress in 1774; he was present and signed the glorious act of Independence in 1776; and invariably continued a member of Congress, from the first Congress till his death, whenever the law requiring a rotation in the representation admitted it.

In the time of the war he was a member of the Governor’s Council of safety of this State.

About the close of the late war, the Legislature of this State resolved, that the laws of the State should be revised and amended; and Mr. Sherman was one of a committee of two, to whom this service was assigned; their proceedings being subject to correction by the Legislature itself : and he performed this arduous service with great approbation.

In 1787he was appointed by the State a delegate to the General convention to form the federal constitution of the United States; and he acted a conspicuous part in that business. In the convention of this State to deliberate concerning that constitution, he had a great influence toward the adoption of it by this State.

On the General adoption and ratification of the constitution, he was elected a representative of the State in Congress. As this office was incompatible with the office of a Judge, he then resigned the latter and sustained the former till the year 1791, at which time a vacancy for this State happening in the Senate of the United States. He was elected to fill it; and in this office he continued till his death.

On repeating thus briefly the history of this eminent and excellent man, it is worthy of remarks, that though he sustained so many different offices in civil government, to all which he was promoted by the free election of his fellow-citizens, and in most of which he could not without a new election, continue longer than a year; in the rest, except one, he could not without a new election, continue longer than two, three or four years; and although for all these office there were, as there always are in popular Governments, many competitors at every election : yet our deceased friend was never removed from any one of them, but by promotion or by act of legislature requiring a rotation, or rendering the offices incompatible with each other. Nor with the restriction just mentioned, did he ever lose his election to any office, to which he had been once elected, excepting his election as a representative of the town in the Legislature of the State; which office we all know, is almost constantly shifting. This shows how great a degree and how invariably he possessed the confidence of his fellow-citizens. They found by experience, that both his abilities and his integrity merited their confidence.

Beside this brief history, perhaps some further account of Mr. Sherman will on this occasion be expected.

I need not inform you, that this person was tall, unusually erect and well proportioned, and his countenance agreeably and manly. His abilities were remarkable, not brilliant, but solid, penetrating and capable of deep and long investigation. In such investigation he was greatly assisted by his patient and unremitting application and perseverance. While others weary of a short attention to business, were relaxing themselves in thoughtless inattention or dissipation, he was employed in prosecuting the same business, either by revolving in his mind and ripening his own thoughts upon it, or in conferring with others.

It has been observed, that he had a taste for general improvement and did actually improve himself in science in general. He could with reputation to himself and improvement to others converse on the most important subjects of theology. I confess myself to have been often entertained, and in the general course of my long and intimate acquaintance with him, to have been much improved by his observations on the principal subjects of doctrinal and practical divinity.

But his proper line was politics. For usefulness and excellence in this line, he was qualified only not by his acute discernment and found judgment, but especially by his knowledge of human nature. He had a happy talent of judging what was feasible and what was not feasible, or what men would bear, and what they would not bear in government. And he had a rare talent of prudence, or of timing and adapting his measures to the attainment of his end. By this talent, by his perseverance and his indefatigable application together with his general good sense and known integrity, he seldom failed of carrying any point in government which he undertook and which he esteemed important to the public good. His abilities and success as a politician were successively proved in the Legislature of this State and in Congress; and his great and merited influence in both those bodies, has been, I believe, universally acknowledged.

As he was always industrious, he was always ready to discharge the various duties of his various offices. In the discharge of those duties, as well as in the more private offices of friendship, he was firm and might be depended on.

That he was generous and ready to communicate, I can testify from my own experience. He was ready to bear his part of the expense of those designs, public and private, which he esteemed useful: and he was given to hospitality.

As he was a professor of religion, so he was not ashamed to befriend it, to appear openly on the Lord’s side, or to avow and defend the peculiar doctrines of grace. He was exemplary in attending all the institutions of the gospel, in the practice of virtue in general and in showing himself friendly to all good men. Therefore in his death, virtue, religion and good men have sustained the loss of a sincere, an able and a bold friend, a friend who was in an elevated situation, and who was therefore by his countenance and support able to afford them the more effectual aid.

In private life, though he was naturally reserved and of few words, yet in conversation on matters of importance, he was free and communicative. With all his elevation and all his honors, he was not at all lifted up, but appeared perfectly unmoved.

In the private relations of husband, father, friend &c. he was entirely kind, affectionate, faithful and constant.

In short, whether we consider him in public or private life; whether we consider him as a politician or a Christian, h he was a great and a good man? The words of David concerning Abner may with great truth be applied on this occasion; Know ye not, that there is a great man fallen this day in Israel?

To have sustained so many and so important public offices, and to have uniformly sustained them with honor and reputation; to have maintained an amiable character in every private relation; to have been an ornament to Christianity and to have died in a good old age, in the full possession of all his honors, and of his powers both of body and mind, is a very rare attainment and a very happy juncture of circumstances.

From this brief survey of the character of this our excellent friend, we see our loss and how great are the tokens of divine displeasure, which we suffer this day. The loss is great to our whole country, the United States, for he was still capable of eminent usefulness. It is great to this State; it is great to this city, of which he was the first magistrate; it is still greater to this church and society, of which he was so amiable, eminent and useful a member; but it is greatest of all to his family.

Yet there are not wanting motives of consolation in these cases. God lives and reigns; let us make up our refuge and our strength, he is able to help us in all our trouble. He is able to take care of the United States, of this State, of this City, of this church and society and of the bereaved family. The direction of God himself is, Leave your fatherless children, I will preserve them alive, and let your widows trust in me. The death of this our friend may be designed in mercy to his children : it may be designed to lead them to think more of death and the eternal world, and more of the necessity of preparation for death, and to exite them actually to prepare, by choosing God for their father and by making him their refuge and strength. Thus their present loss, thought great, may be the happy mean of their unspeakable gain. Also it may lead the widow to rely more on her Creator.

May not only the bereaved widow and Children make such an improvement of this afflictive dispensation, but may we all do the same; that when death shall overtake us, as it will very soon, we may have God for our father and friend to conduct us safe through the valley of the shadow of death and afterward to receive us to glory.

Endnotes

1. Hence With great propriety the poet speaking of the declaration of independence by Congress, in which Mr. Sherman acted a distinguished part, says,

The self taught Sherman urged his reasons clear.

Humphreys’ Poems.