Shortly after the December 2012 mass shooting of children and teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, many began calling for severe limitations on private gun ownership and even a complete repeal of the Second Amendment, with its constitutional guarantee for citizens to “keep and bear arms.” David Barton was invited on a one-hour national television program to provide an historical perspective on the issue of gun ownership and gun control. In that one hour show, he presented colonial laws, early state constitutional provisions, statements from the Founding Fathers, positions of various presidents, and court decisions on the issue from both past and present.

In one part of the program, David specifically noted that even in the aftermath of the shootings of Presidents Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, John Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan, there were not calls for gun control – that even Reagan (while lying in the hospital recovering from the wound) voiced opposition to such efforts.1 None of these shootings was used as a reason to immediately call for increased regulation of guns, as was done by President Obama in the aftermath of Sandy Hook (thus applying Rahm Emanuel’s axiom to never let a crisis go to waste). But several of David’s obsessive critics, being more concerned with opportunism than truth or context, quickly took to websites and blogs claiming that his statement concerning Reagan was erroneous – that Reagan did support gun control.2 But David’s statement was completely accurate, for it was ten years after Reagan was shot, and three years after he left office before he declared support for the Brady gun control bill. David had made very clear that his context was presidential responses in the aftermath of shootings; and President Reagan, unlike President Obama, had not used an emotional national crisis to call for gun control.

In another part of the program, David pointed out the Founding Fathers’ emphasis on young people being taught the use of guns from an early age, believing that early training increased gun safety and decreased gun accidents and injuries. This view was clearly articulated by John Quincy Adams.

When he was dispatched by President James Madison as America’s official Minister to Russia, he left his three sons in the care of his younger brother, Thomas. Arriving in St. Petersburg, Adams wrote with specific instructions regarding the education and training of his boys (George, age 9; John, age 7; and Charles, age 3), telling his brother:

One of the things which I wish to have them taught – and which no man can teach better than you – is the use and management of firearms. This must undoubtedly be done with great caution, but it is customary among us – particularly when children are under the direction of ladies – to withhold it too much and too long from boys. The accidents which happen among children arise more frequently from their ignorance than from their misuse of weapons which they know to be dangerous.3

Expressing similar views, Founding Father Richard Henry Lee, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a framer of the Bill of Rights, declared:

[T]o preserve liberty, it is essential that the whole body of the people always possess arms, and be taught alike, especially when young, how to use them.4

Thomas Jefferson likewise advised his young fifteen year-old nephew:

In order to assure a certain progress in this reading, consider what hours you have free from the school and the exercises of the school. Give about two of them, every day, to exercise; for health must not be sacrificed to learning. A strong body makes the mind strong. As to the species of exercise, I advise the gun. While this gives a moderate exercise to the body, it gives boldness, enterprise, and independence to the mind. Games played with the ball, and others of that nature, are too violent for the body and stamp no character on the mind. Let your gun therefore be the constant companion of your walks.5

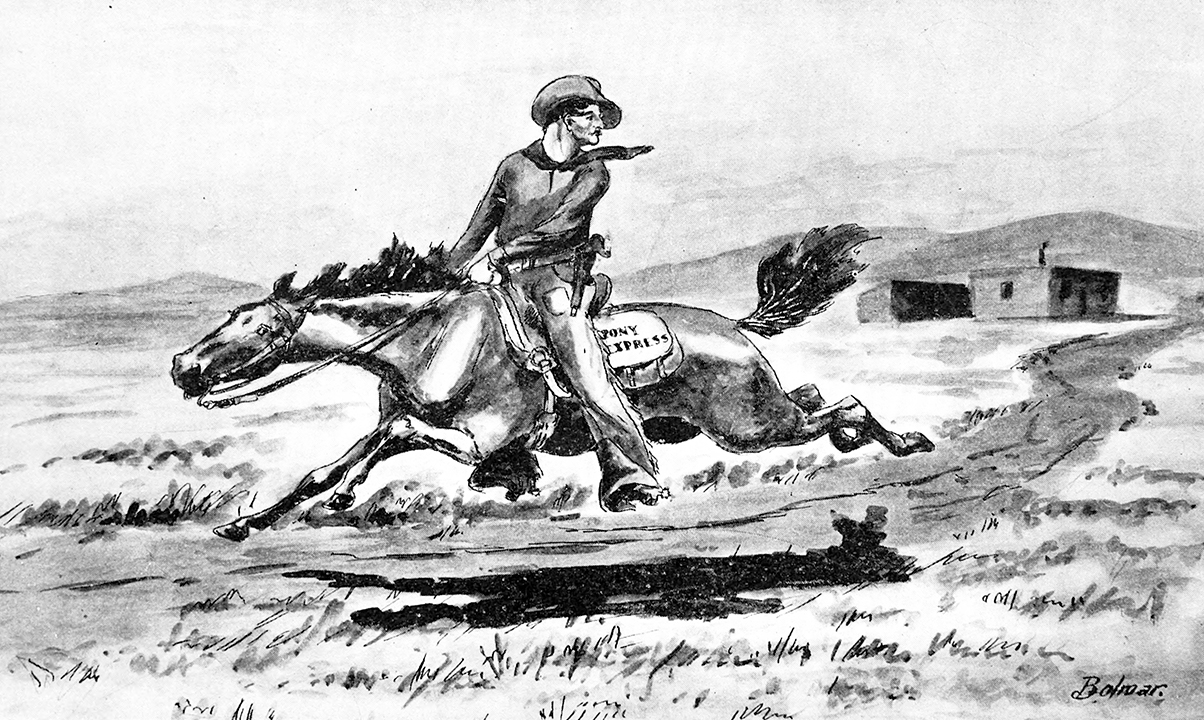

Having established the early American view of training children with the use and handling of guns, David explained that this practice continued for generations thereafter, even citing an example of students in the Old West who drew their guns at a school house in order to protect their teacher from a potential shooter. But David’s critics, being unfamiliar with that story and finding it inconceivable that previous generations could possibly think different about guns than they themselves do today, once against took to websites and blogs, claiming that David had made up this story, or that it was completely fictional.6 They were again wrong.

The account comes from noted western historian, Louis L’Amour, one of the most famous writers of both historical western fiction and non-fiction. L’Amour amassed a personal library of as many as 17,000 rare books/diaries/journals/documents7 particularly focusing on the American west, including numerous handwritten journals of frontier pioneers and settlers. Additionally, he personally interviewed many personalities who had lived in the waning days of the Old West, including gunfighters, cowboys, lawmen, outlaws, and many others.8 For his outstanding body of work across his lifetime, he received the Congressional Gold Medal and then the Medal of Freedom from President Ronald Reagan.9

Later in life, L’Amour recorded a number of interviews, relating interesting practices and incidents he had found in his research. In one such interview, he related the specific account (what he called “a true incident”)10 that David cited – a real-life story that he also included in one of his historical novels11 (he regularly included numerous true stories and anecdotes from the Old West throughout his stories). So not only did David not make up the anecdote, it actually came from one of America’s most celebrated western historians, who personally attested to its authenticity.

Proverbs 18:17 reminds us that one side sounds right until the other side is presented. The critics presented their side; David presented the truth. Proverbs 18:2 states that “A fool has no delight in understanding, but in expressing his own heart,” and several of David’s fixated critics have certainly done this, raising objections and expressing the hate in their heart without adequately researching their claims. For this reason, we always encourage folks to be thorough in their research and get the rest of the story before reaching a conclusion.

Incidentally, for those interested, L’Amour’s interview that includes the account of the students with guns at school follows below.

Interview with Louis L’Amour

Audio CD: South of Deadwood

“Deadwood, South Dakota was a wild boom camp that opened up in the Black Hills after the Indians were pushed out. There’s a lot of dispute about the Black Hills now about who they belonged to, but as a matter of fact, it’s very doubtful whether the Indian tribe had much of a claim on them. The Kiowa’s had them for a while and the Sioux drove the Kiowa’s out and the Sioux now claim that they were pushed out by the white man and want to be paid for it. But why not the Kiowas the Sioux drove out? And the Kiowas drove somebody else out; this was the way of things.

But Deadwood was a boom camp that started there. Some of Custer’s men, they were exploring the Black Hills found gold; and they found gold in several places. But Deadwood was where they found most of it. It started around a group of mines or a mine in particular and it did sprawl on the whole side of the canyon there, and there was a lot of dead wood up on the inside of the other and knocked down by, I imagine by wind (that will do it occasionally). I know a place in Colorado where there was a whole forest lining the side of a hill that a sudden wind blew the trees down. But anyway, Deadwood was very, very famous for that.

And Deadwood burst into growth out of nowhere. Buildings and tent houses and everything sprang up along the street and then the people began to come in: the gamblers and the women and the men who were doing the mining and the men who were trying to take the money away from those who brought it out of the ground. And Deadwood was rough and tough. That was where Hitchcock was killed sometime later, shot in the back. There was a sheriff round there for a while named Seth Bullock; he was quite a well-known man, he was a merchant later in Montana. But he was not a gun fighter at all, just a stern quiet man who knew his business and went about it and was very highly respected.

Calamity Jane was around there for a while, but Calamity Jane was really nobody in the West. The only thing she’s remembered for is because she had that tricky name. She was a prostitute of a particular low order and not good looking enough to do much business in town, so she did her business out on the road with traveling wagon trains.

But it was wild and rough and at one time or another nearly all the gunfighters showed up there. There was a very well-known gunfighter at that time who’s been forgotten pretty much since named Boone May. He was a police officer there, deputy sheriff I should say, and probably as good with a gun as any of the others that you’ve heard about. But he didn’t acquire the reputation.

It was a wild, rough town. There’s a very good book written about it by a woman named Estelle Bennett, whose father was a judge there, who had a quite fine library. And he handled a lot of the cases there in town, and Estelle Bennett was a little girl growing up there when all this was going on. She tells a good account of it.

See, sometimes people wonder how we know about what happened in the West. They think you have to have a good imagination. You don’t. Because there were people there at the time who were writing down what happened, you don’t have to imagine; you know. There are diaries every place, and nearly every town had its newspaper (some had two), that were recording the facts right at the time. You know all about these people; you can check everything right from beginning to end.

What you have to understand is that there were generally two sections in any western town. There was the people on the wrong side of the tracks you might say – the saloons and the red light district and all that, and that’s where most of the rough stuff went on. At the same time this was happening, at the same time that gunfights were going on and everything, on the other side of the track there were churches and schools and people going on and carrying on their lives the way any normal people would. And sometimes all they knew about the gunfights was the sound of the gunfire. They didn’t know who was shooting who until they heard it later. But among the rougher crowd, and among the cowboys in the neighborhood, gunfighters were treated about like baseball stars or football stars now. People talked about their various abilities and what would happen if two of them came together and who would be better than who, you know? And this was a discussion that went on quite often, and it was rough; very rough.

And the saloons in those days were not just a place where you went to drink. They were clearing houses for information. Many of the men who went to saloons didn’t drink at all. But you would go in there, and there at the bar or at the card tables you could get information on any part of the country or anybody you wanted to know. If you wanted to know about the marshal in a certain town, you could ask somebody; they would always know. Or they’d always know where a trail was. And if you happened to be a little bit careful about it, and listen a lot, and ask questions very discreetly, you could find out where the outlaw hideouts were, cause there was always somebody around who knew.

And you see, actually, the West was a relatively small place. It was huge in area, but there weren’t many people. And when a cattle drive, for example, started in Texas to go north to Dodge City or Abilene or Oklahoma or Nebraska or wherever they were going, a man would sit down and draw a trail for them in the dust or the clay, or maybe on a piece of paper in a barroom, and show them where they had to go. And usually he would tell them also about the town marshal in those various towns, he’d tell them about Wild Bill Hickok, or Mysterious Dave Mathers, somebody like that, and how they had to be careful of this man, he was dangerous. So, it was relatively a small world and there was really no place to hide in the West. Once you got out there and people knew you by some name or another, they never asked you what your name was. If you told them a name – and you could say “I’m Shorty” – that was all they ever recognized you by. Or if you said your name was “Mr. John B. Ellison,” they just accepted that. They didn’t ask what your background was, or where you came from, or who you were, or where you went to school – anything. They just took you at your own word. If you came round a ranch and stopped by for some food or something (what they used to call “riding the grub line”), you could stop at any ranch, and any ranch would feed you. So nobody asked you your name or anything; if you wanted to volunteer it, that was up to you. If you had some distinction, they might refer to you by that; they might call you “Red,” or “Shorty,” or “Slim.” I was on a circus briefly where there were about five or six “Shorty’s” and seven or eight “Slim’s,” so they got to designating them as “Overland Slim” and “Red Slim” and that sort of thing.

All kinds of people came west, some of them with pretty bad records behind them. The West was a natural magnet for any adventurer, any drifter, anybody who was at loose ends. So men came there from all over the world, not just from America, but from other countries as well. They came there from Australia, from France, from England. We had a man up in North Dakota, called Marquis de Morès, who built a chateau out on the western plains and ran cattle out there. A very handsome man. He even got in a couple of gun battles. But he was a friend of Teddy Roosevelt also, or at least they were acquainted. And there were others that came. For example, a little-known fact is that five of the men who died with Custer at the Little Bighorn had been members of the Vatican Guard. You never knew who you were talking to in the West.

Once up, I think it was in Idaho, there were some miners sitting round a table and one of them had brought a newspaper into the area. Now newspapers were very rare and hard to come by. So he was reading the paper aloud to all these miners while they’re eating. He was reading everything to them because it was all news to them. And he came to an account of the rowing match between Cambridge and Oxford on the Thames River. And one man sitting down at the end of the table looked up and said, “I used to row on that team.” And he had. You see, you never knew who you were talking to.

There were people out there who were titled men. For example, we have a senator in Washington right now who is the descendant of a titled man: Senator Wallop. Oliver Wallop came over here from England and ranched in the plains of Wyoming for thirty years. And then went back and took a seat in the House of Lords. So you never knew who you were talking to.

But Texas, due to the kind of country it was, developing very rapidly, and with men who were fiercely proud and fiercely independent, naturally gravitated toward the use of guns. There were outlaws, there were Indians, so everybody had to carry the gun from necessity. Even children going to school did. Actually, many of the gunfighters were very young. If a man lived to be, say, thirty-five years old as a gunfighter, usually he lived forever, or for a long, long time. But the fellows who were in most of the gunfights were anywhere from seventeen to twenty-five. After that they began to realize that they were vulnerable too, and they began to be more careful about their gun battles. But they were mostly young. There was no such thing, really as a juvenile delinquent in those days. A boy went right from being a boy in knee pants to being a man. And that’s what he wanted to be more than anything else in the world. He wanted to be a man, and be accepted as a man, and welcomed as a man, and do a man’s work; and that was the important thing for him. So as soon as he got to that point, he’d established himself to a degree, and he was very proud of the fact that he had. But some of them went overboard, and some of them became killers and became very vicious. And if you were old enough to carry a gun, you were old enough to get shot. It was your problem.

There’s a case I use in one of my stories; I use it in the story called Bendigo Shafter. All the kids coming to school used to hang their guns up in the cloakroom because they were miles from home sometimes, and it was dangerous to ride out without a gun. And this is taken from an actually true incident. (emphasis added) I use it in my story and tell the story, but it really happened. Now a man came to kill the teacher. It was a man. And he came with a gun, and all the kids liked the teacher, so they came out and ranged around him with their guns. That stopped it. But kids twelve and thirteen used to carry guns to school regularly.”

Endnotes

1 “Gun Control: Reagan’s Conversion,” Time Magazine, April 8, 1991.

2 Warren Throckmorton, “Did Ronald Reagan oppose James Brady on gun control? No, David Barton, Reagan favored the Brady Bill,” Warren Throckmorton, January 16, 2013.

3 John Quincy Adams, Writings of John Quincy Adams, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914), III:497, to Thomas Boylston Adams on September 8, 1810.

4 Richard Henry Lee, An Additional Number Of Letters From The Federal Farmer To The Republican (New York: 1788), 170, Letter XVIII, January, 25, 1788.

<5 Thomas Jefferson, Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies, ed. Thomas Jefferson Randolph (Charlottesville: F. Carr, and Co., 1829), I:287, to Peter Carr on August 19, 1785.

6 Chris Rodda, “Is David Barton Now Getting His ‘History’ from Louis L’Amour Novels?” Huffington Post, February 4, 2013; Warren Throckmorton, “What’s the source for David Barton’s Kids with Guns Sotry?” Warren Throckmorton, February 4, 2013.

7 “America’s Favorite Storyteller,” The Louis L’Amour Collection (accessed on February 14, 2013). See also “A Brief biography of Louis L’Amour,” The Official Louis L’Amour Website (accessed on February 14, 2013); Donald Dale Jackson, “World’s fasted literary gun: Louis L’Amour,” Smithsonian Magazine, 1987.

8 Donald Dale Jackson, “World’s fasted literary gun: Louis L’Amour,” Smithsonian Magazine, 1987.

9 “Louis L’Amour Biography,” Bio. True Story (accessed on February 14, 2013).

10 Louis L’Amour, South of Deadwood (New York: Random House Audio, 1986).

11 Louis L’Amour, Bendigo Shafter (New York: Bantam Books, 1979), 164.

Why was Jefferson a faithful attendant at the Sunday church at the Capitol? He once explained to a friend while they were walking to church together:

Why was Jefferson a faithful attendant at the Sunday church at the Capitol? He once explained to a friend while they were walking to church together:

too, have American Presidents – as in 1947 when President Harry Truman quoted the Supreme Court, declaring:

too, have American Presidents – as in 1947 when President Harry Truman quoted the Supreme Court, declaring: