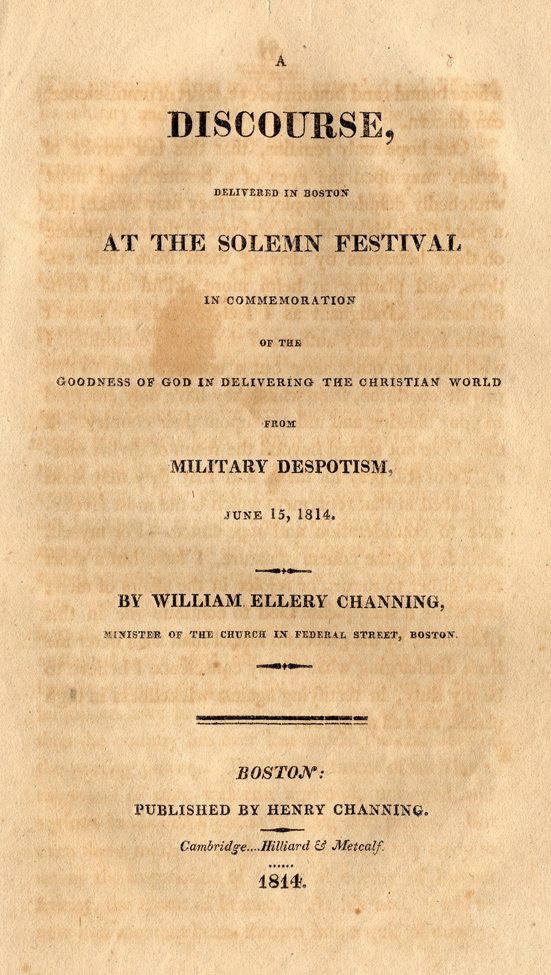

William Ellery Channing (1780-1842) was the grandson of one of the Newport Sons of Liberty, John Channing. William graduated from Harvard in 1798 and became regent at Harvard in 1801. He was ordained a preacher in 1802 and worked towards the 1816 establishment of the Harvard Divinity School. This sermon was preached by William Ellery Channing in Boston on June 15, 1814.

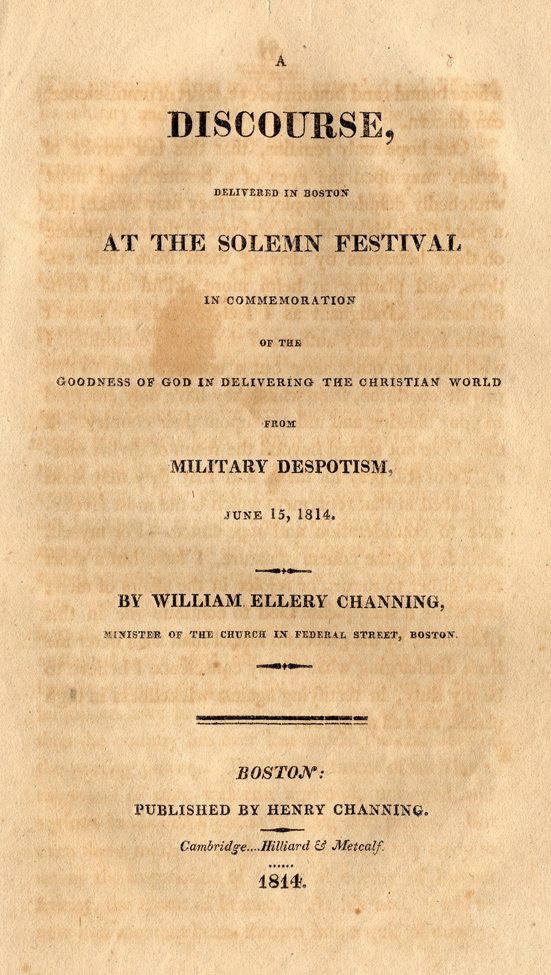

ADISCOURSE,

DELIVERED IN BOSTON

AT THE SOLEMN FESTIVAL

IN COMMEMORATION

OF THE

GOODNESS OF GOD IN DELIVERING THE CHRISTIAN WORLD

FROM

MILITARY DESPOTISM,

JUNE 15, 1814.

BY WILLIAM ELLERY CHANNING,

MINISTER OF THE CHURCH IN FEDERAL STREET, BOSTON

DISCOURSE.

REV. xix. 6.

HALLELUJAH: FOR THE LORD GOD OMNIPOTENT REIGNETH.

It is the dictate of reason and revelation, that God is to be acknowledged in all the events of life, and changes of society. In adversity, his hand is to be adored with uncomplaining resignation; and in prosperity, his goodness is to be celebrated with joy and thanksgiving. Through inferior agents our thoughts should always rise to God, in whom all other beings live and move, and without whom not a sparrow falls.

In conformity to these just and exalted views of God, we are now assembled to offer him our tribute of praise and gratitude for the deliverance he has vouchsafed to the civilized world. We are assembled to bear our part in the joyful thanksgivings which are now ascending to him from liberated nations. Let us bring to his throne the sentiments which this solemnity demands. Let our exultation be purified from all narrow and unworthy feelings. As members of the great human family, and in the spirit of universal charity, let us offer sincere praise to our common God and Father, who has sent this great salvation to his suffering children.

Do any doubt the propriety of our expressions of joy on the deliverance of Europe, because the influence of this event on ourselves in not precisely ascertained? To such doubts I might reply, that the cause of this country is necessarily united with the cause of the world. I might say, that every free and enlightened people has an interest in the freedom and improvement of other nations; that there is a sympathy, a contagion of spirit and feeling, among communities as well as individuals; and that the slavery of Europe would have fastened chains on us. I might say, that the fallen despot of Europe had not forgotten this country in his scheme of universal conquest, that his disastrous influence has already blighted our prosperity, and that if peace and honour are to revisit our shores, we shall owe these blessings to the fall of the oppressor. But obvious reasons forbid me to enlarge on topics like these. Let it be granted, that other nations are to participate more largely than we in the blessings of this happy revolution. And shall we therefore be dumb, amidst the shouts and thanksgivings of the world? Is it nothing to us, that other nations are blest? Does the ocean which rolls between us, sever all the charities, extinguish all the sympathies, which should bind us to our kind? Can we hear with indifference that the rod of the oppressor is broken, because other nations were crushed with its weight? Away this cold and barbarous selfishness! Nature and religion abhor it. Nature and religion teach us, that we and all men are brethren, made of one blood, related to one father. They call us to feel for misery, wherever it meets our view; to lift up our voices against injustice and tyranny, wherever they are exercised; and to exult in the liberation of the oppressed, and the triumphs of freedom and virtue through every region under heaven. We are not indeed to forget our homes in our sympathy with distant joy and sorrow; and neither are we to suffer the ties of family and country to contract our hearts, to separate us from our race, to repress that diffusive philanthropy, which is the brightest image man can bear of the universal Father. God intends that our sympathies should be wide and generous. We read with emotion the records of nations buried in the sepulcher of distant ages – the records of ancient virtue wresting from the tyrant his abused power; and shall the deliverance of contemporary nations, from which we sprung, and with which all our interests are blended, awaken no ardor, no gratitude no joy?

It is an animating thought, that we, my friends, have a peculiar right to rejoice in the prosperity of Europe, because we mourned with her in the day of her adversity. Our hearts bled with her, when she lay a mangled victim at the foot of her oppressor; and who will forbid us to hail her with delight, now that she rises from the dust in renovated life and glory. As a nation indeed, we have no right to participate in the general joy. As a nation, we cannot gather round the ruins of the fallen despotism, and say, We shared in the peril and glory of its destruction. But it is the honour of this part of the country, that in heart if not in act, with our prayers if not our arms, we have partaken the struggles of Europe. In this day of our country’s disgrace we can say, and the world should know it, that we never sung the praises of the tyrant, never joined the throng which offered him incense and bent before him the servile knee. We have had no communion of interest or feeling with the enemy of mankind. We abhorred the prosperous, as much as we contemn the fallen tyrant. Let history, when she records the connection of this republic with the usurper, bear witness, that we were not all involved in this disgrace, that there were some among us true to the cause of human nature, whose hearts sunk under the depression of Europe, and whose hearts leaped for joy, when Europe was free.

Europe then is free! Most transporting most astonishing deliverance! How lately did we see her sitting in sackcloth and ashes; and now she is arrayed in the garments of praise and salvation. Instead of the deep and stifled groans of oppression, on general acclamation now bursts on us from all her tribes and tongues. It ascends from the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Appenines. It issues from the forests of the north. It is wafted to us on the milder winds of the south. In every language, the joy inspiring acclamation reaches our ears, THE OPPRESSOR IS FALLEN, AND THE WORLD IS FREE.

Will you say, that this joy is excessive? It cannot rise to the height of the deliverance by which it is inspired. What despotism was ever so degrading so appalling, so fatal to the best interests of mankind, as that whose subversion we this day celebrate. The fairest portion of the world was its prey, and the most flourishing regions were laid waste by its fury. From Moscow to the shores of the Mediterranean, you may discern in the ruins of cities, and in desolated and deserted plains, the track of this relentless despotism. It was a despotism founded in crime, cemented in blood, and all its splendor was derived from the spoils of an oppressed world. Its ambition knew no bound, and submitted to no restraint. It had no pity for the weak, no justice for the innocent, no regard to plighted faith, no settled end but universal empire. It was sustained by armies disciplined to victory, hardened to cruelty, exulting in success, inflamed with the hope of rapine, and led by generals whose names were a host. Before it went menace, terror, corruption, fraud, and every profligate art, to prepare its way; and behind it were desolation, famine, and slavery. At its presence the old and revered institutions of Europe fell; thrones and governments, which had endured for ages, were overturned. If indeed the former sovereign was permitted to hold his power, he held it as a fief and dependence on the usurper, and was bound to pay for this poor relic of departed greatness, by contributing the treasures and blood of his kingdom to adorn and sustain the despotism by which he was crushed. Wherever this dreadful power was establish4ed, virtue, patriotism, and honour were driven into obscurity, and spies and traitors exalted. This vicious despotism linked with itself the vice of every country. It infused life, energy, and hope into the profligate, mercenary, restless, and desperate, and rewarded them with the plunder of the country they betrayed. Wherever this despotism spread, the press was in chains, and fear chained every tongue. The ordinary pursuits of industry were interrupted. On the once busy and peopled shore, a host of guards watched every sail, and the peasant with a fainting heart tilled the fields, which might be trodden down by armies, or pillaged by lawless rapacity. Every where commerce, the golden chain of nations, the spring of enlarged philanthropy, the disperser of art, science, and improvement, was discouraged by bloody edicts. The old connections of Europe were systematically broken up, and hardly any connection seemed to remain but union to the central despotism.

The moral influence of this despotism, more than all things else, gave it a character of peculiar horror, and should excite our most fervent gratitude for its destruction. It was despotism of low and vulgar minds. It had nothing of greatness and elevated sentiment. It not only destroyed like a beast of prey; but it polluted, like a harpy, what ever it touched. Its breath was poison, tainting the atmosphere, and changing its victim into a loathsome mass of corruption. It left not merely a wilderness in the natural world – it desolated the mind, and robbed human nature of all its honourable attributes. We could have forgiven it, had it only robbed and impoverished, but it degraded Europe. It systematically corrupted, that it might enslave. By its undisguised and unblushing crimes, and its open and successful contempt of the principles of justice, it shook the moral sentiments of mankind, and taught them to look with the indifference of familiarity on deeds, which would once have struck them with horour. Nothing can be imagined more hostile to the authority of conscience and virtue, than the triumphs of a power, which defies God, and honours and recompenses crime. These triumphs every where offered themselves to the eyes of Europe and in the world was a despot, black with crimes, the dark features of whose character were not brightened by a gleam of virtue. His throne was sustained by tributary princes and besieged with flatterers and servile dependents. O that this page were torn from the history of Europe! Never did Europe know so dark and dishonourable a day, as when her princes and nobles, her genius, learning, and eloquence gathered round a base adventurer to do him homage, – to do homage to treachery and murder.

My friends, with what aching eyes did we look on this scene of degradation! The light of the world seemed to us expiring. Europe, the land of our fathers, the land of Christians, the abode of civilization and refinement, crowned with splendid cities and cultivated fields, with venerable temples, ancient seats of science, asylums for human misery, and unnumbered institutions, which embellish, console and refine the social state, Europe, so flourishing, so interesting, the best hope of the world, seemed to us given into the hand of the destroyer.

Such, my hearers, was the despotism, which God in his holy providence permitted to arise in the center his holy providence permitted to arise in the center of the civilized world – so ferocious, so appalling – and IT IS FALLEN, IT IS FALLEN! At the moment of its greatest glory, when its foundations seemed to the gloomy eye of fear firm as the hills, and its proud towers had pierced the skies, – the lightning of heaven smote it, and IT FELL! Most holy, most merciful God thine was the work; thine be the glory! Who will not rejoice? Who will not catch and repeat the acclamation, which flies through so many regions, – THE OPPRESSOR IS FALLEN, AND THE WORLD IS FREE!

What a delightful change meets our view in the face of Europe! The flag of Orange and independence again waives on the spires of Holland. The song of cheerfulness and freedom again ascends the cliffs of Switzerland. Spain and Portugal, deluged as they are with blood, tell us they have not bled in vain, for perfidy has met its’ reward, and no hostile foot now pollutes their fields. Prussia, lately trampled in the dust, now lifts her head in exultation, and points us to her veteran hero and valiant hosts, who have wiped away her dishonour and fought with glorious success the battles of the world. Russia shows us her fields, whitened with the bones of invading armies, which never before knew defeat; and tells us, that she first rolled back the tide of oppression, and gave hope to subjugated nations. Even France calls us to participate her joy, for her sceptre is wrested from the tyrant, and wielded again by a benignant sovereign, who will heal her wounds, and grant her the repose she has so long denied to the world. How changed the face of Europe! The universal tumult of war is now hushed. The patriot now pronounces the name of his country without a blush, for it no longer stoops to the oppressor. The deserted shores begin to resound with busy multitudes, and to whiten with the sails of commerce. The exile returns to his ravaged fields with cheerfulness and hope. The fettered tongue is loosened, and exults without fear in the fall of the tyrant. That power which encouraged crime is now prostrate and its wrecks strew the nations; and if its prosperity emboldened guilt, its ruin speaks in a deeper tone the wretchedness of unprincipled greatness. Who will not rejoice? Who will not participate in the triumphs and gratitude of liberated nations?

I have hitherto called you to rejoice in the fall of the despotism, which has threatened the world. I would now direct you to that most auspicious instructive event, the fall of the despot. My hearers, where is the man, at whose nod nations lately trembled, at whose pleasure kings held their thrones, and whose voice, more desolating than the whirlwind directed the progress of ravaging armies? Behold and adore the righteous judgments of God! A little island now holds this conqueror of the world. No crowd is there to do him homage. His ear is no longer soothed with praise. The glare which power threw around him is vanished. The terror of his name is past. His abject gall has even robbed him of that admiration, which is sometimes forced from us by the stern, proud spirit, which adversity cannot subdue. Contempt and pity are all the tribute he now receives from the world he subdued. If we can suppose, that his life of guilt has left him any moral feeling, what anguish must he carry into the silence and solitude, to which he is doomed. From the fields of battle which he has strewed with wounded and slain, from kingdoms and families which he has desolated, the groans of the dying, the curses of the injured, the wailing of the bereaved, must pierce his retreat, and overwhelm him with remorse and agony.

Here let us learn my friends, never to be dazzled by triumphant guilt, never to forget the crimes of a usurper in his success. Let us learn, that virtue alone deserves our veneration, and that virtue alone will endure. The adulation of the courtier and the homage of the blinded crowd cannot sustain that greatness, which is reared on guilt. The most dreaded and flattered despot is after all but a man, exalted to his bad eminence for the chastisement of a guilty world, and destined to magnify, by his own destruction, the Almighty justice he has defiled. Let not the bloody conqueror boast of his poers. The blood which he sheds, the regions which he wastes, the widows and fatherless whom he bereaves, the poor whom he drives from their homes to perish by cold, famine, and sickness, all cry to God, and draw down on his head deserved destruction.

My hearers, from the events which we this day celebrate, we are especially taught that most important lesson, to hold fast our confidence in God and never to despair of the cause of human nature, however gloomy and threatening be the prospect which spread before us. How many of us have yielded to criminal despondence! How many of us saw, in imagination, the last blow given to national independence, when the usurper poured his hosts into the north! The shouts of new victories already seemed to reach our ears. We now see, that what we dreaded wrought our safety; that the appalling greatness of the usurper, by inspiring presumption, hastened his ruin; that the very rapidity of his progress brought him more surely and more suddenly to the precipice. Slower conquests might have quenched the spirit of nations, and induced new habits in the vanquished. But the impatient usurper, in grasping new dominions, neglected to secure his former acquisitions. In the vanquished there burned a smothered indignation, ready to break forth at the first moment of hope. That moment came – it was hastened by the mad temerity, which success had inspired. Europe rose in her strength, burst her chains with one convulsive effort, and suddenly prostrated the throne which the toils of years had erected. We are here taught, as men, perhaps, were never taught before, to place an unwavering trust in providence, to hope well for the world, to hold fast our principles, to cling to the cause of justice, truth, and humanity, and to frown on guilt and oppression, however dark be the scenes which surround us, and however dangerous or deserted be the path of duty.

Let me close this discourse, with dwelling for a moment on the cheering prospects opened on the world by the fall of the usurper. We are at length permitted to anticipate the long lost and long desired blessing of general and permanent peace. Peace, whilst that usurper held the throne, would never have revisited Europe; or at least no peach but that of silent, motionless, unresisting slavery. War was his element. He was bred to scenes of tumult and blood. He knew no excellence, but that of wielding weapons of destruction, and had no ambition but to erect arches and monument of victory. But the weapons are now wrested from his hands. That perturbed spirit no longer controls the nations. Europe, bleeding under so many wounds, sighs for peace; and we may hope that, taught by tremendous experience, she will shrink, at least for a season, from the renewal of war. In France a most solemn and monitory example has been given of the ruinous effect of the passion for conquest. The woes, which that aspiring people have inflicted on other nations, have rolled back on themselves. A military despotism has ground them in the dust, wrung from them their substance, torn from them their children, and made every family a mourner. The blood of Frenchmen has flowed in streams over the fields of almost every nation in Europe. And not only have they bled at a distance : invasion and conquest have rushed on their own plains, and penetrated to the very heart of their empire – and will the nations of Europe, with his solemn example before their eyes, still pant with undiminished ardor for ware and universal conquest? May we not also hope, that the spirit of peace will be cherished and diffused by the late generous successful struggle, in which all Europe, with one heart and one hand, has beaten down unprincipled ambition and military despotism?

But still greater blessings may be anticipated. I consider the fall of the usurper, and of his power, as the death blow to that system of Atheism and infidelity, which has been the chief source of the miseries of Europe. The French revolution was cradled in Atheism. Its authors hated God, and scoffed at futurity, and boasted that the throne of heaven was to sink in the same ruing with earthly monarchies. Since that period, a most solemn experiment has been making on society. The nations of Europe, which had in all measure been corrupted by infidel principles, have been called to witness the effects of these principles on the character and happiness of nations and individuals. The experiment is now completed; and, I trust, Europe and the world are satisfied. Never, I believe, was there a deeper conviction than at the present moment, that Christianity is most friendly to the peace, order, liberty, and prosperity of mankind, and that its subversion would be the ruin of whatever secures, adorns, and blesses social life. Europe, mangled, desolated Europe, now exclaims with one voice against the rule of atheism and infidelity, and flies for shelter and peace to the pure and mild principles of Christianity. Already the marks of an improved state of public sentiment may be discerned. Amidst the sufferings and privations of war, a generous spirit for the diffusion of the scriptures has broken forth; and at this moment that sacred volume, which infidelity hoped to bury in forgetfulness with the mouldering records of ancient superstition, is more widely opened than in any former age, to the nations of the earth. This reaction in favor of religion and virtue will, we trust, continue to increase. The fall of the usurper, as we have already observed, is the fall of a government, which depressed the good, and gave confidence and strength to the unprincipled of every region. That terrible example of successful guilt will no longer corrupt. That moral pestilence is stayed; and the remembrance of it, we trust, will carry solemn warning to the most distant generations.

To conclude – a new era seems opening on Europe and the world. We have an auspicious omen in the magnanimity of the victorious allies. We have another, still more auspicious in the new constitution of France, in which the great principles of civil and religious liberty are distinctly recognized before the assembled sovereigns of Europe. It is our hope, that the storm, which has shaken so many thrones, will teach wisdom to rulers, will correct the arrogance of power, will awaken the great from selfish and sensual indolence, and give stability to government, by giving elevation of sentiment to those who administer it. It is our hope, that calamities so awful, deliverance so stupendous, will direct the minds of men to an almighty and righteous providence and inspire seriousness, and gratitude, and a deeper attachment to the religion of Christ, that only refuge in calamity, that only sure pledge of future and unchanging felicity. Am I told, that these anticipations are to ardent? My hearers, I am not forgetful of the solemn uncertainty of futurity. I am aware, that the Unsubdued passions of the human heart still threaten sore and multiplied calamities to the world, Perhaps I have indulged the hopes of philanthropy, where experienced wisdom would have dictated melancholy prediction. But amidst all the uncertainties which surround us, one thing we know, that God governs, and that his most holy and benevolent purposes will be accomplished. One thing we know, that God has mercifully interposed for a suffering world and broken the power of the oppressor. For this most gracious and wonderful deliverance, let every heart thank, and every tongue praise him. Let the heavens rejoice, and the earth be glad. Let the sea roar and the fullness thereof. Break forth into singing ye mountains, and be joyful, ye fields! Kings of the earth, and all people, princes and all judges of the earth, both young men and maidens, old men and children, praise ye the Lord! Praise him with the sound of the trumpet, with the psaltery and harp, with stringed instruments and organs; for his name alone is excellent; for he hath visited and redeemed his people, and his mercy endureth forever.

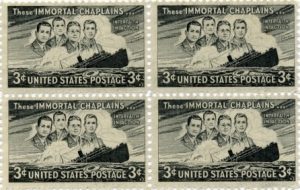

that the last thing they saw was the four chaplains standing together on the submerging deck – a Jew, a Methodist, a Catholic, and a Dutch Reformed – their arms locked together and their voices raised in prayer and song as the ship forever slipped beneath the freezing waters. 5

that the last thing they saw was the four chaplains standing together on the submerging deck – a Jew, a Methodist, a Catholic, and a Dutch Reformed – their arms locked together and their voices raised in prayer and song as the ship forever slipped beneath the freezing waters. 5Their belief, their faith, in His word enabled them to conquer death. 8

However, all of that changed with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. In his famous “date which will live in infamy” message to Congress requesting that the United States officially declare war on Japan, President Roosevelt stated, “With confidence in our armed forces — with the unbounding determination of our people — we will gain the inevitable triumph — so help us God.”

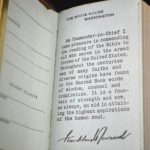

However, all of that changed with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. In his famous “date which will live in infamy” message to Congress requesting that the United States officially declare war on Japan, President Roosevelt stated, “With confidence in our armed forces — with the unbounding determination of our people — we will gain the inevitable triumph — so help us God.” This confidence in God and our military (along with his concern for individual American soldiers) was later evident in what is now known as The Heart-Shield Bible. These Bibles (used during World War II) were designed to fit securely into the chest pocket of a soldier’s uniform. The metal plates were securely attached to the front cover of the Bible to stop a bullet from reaching the soldier’s heart (which they did on several occasions). In our library at WallBuilders we have several of these World War II Bibles. In the back is a section of psalms and hymns, including “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” “America the Beautiful,” and “The Star Spangled Banner.” In the front, there is a note to the soldiers directly from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

This confidence in God and our military (along with his concern for individual American soldiers) was later evident in what is now known as The Heart-Shield Bible. These Bibles (used during World War II) were designed to fit securely into the chest pocket of a soldier’s uniform. The metal plates were securely attached to the front cover of the Bible to stop a bullet from reaching the soldier’s heart (which they did on several occasions). In our library at WallBuilders we have several of these World War II Bibles. In the back is a section of psalms and hymns, including “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” “America the Beautiful,” and “The Star Spangled Banner.” In the front, there is a note to the soldiers directly from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Commander-in-Chief I take pleasure in commending the reading of the Bible to all who serve in the armed forces of the United States. Throughout the centuries men of many faiths and diverse origins have found in the Sacred Book words of wisdom, counsel and inspiration. It is a foundation of strength and now, as always, an aid in attaining the highest aspirations of the human soul.

As Commander-in-Chief I take pleasure in commending the reading of the Bible to all who serve in the armed forces of the United States. Throughout the centuries men of many faiths and diverse origins have found in the Sacred Book words of wisdom, counsel and inspiration. It is a foundation of strength and now, as always, an aid in attaining the highest aspirations of the human soul. We cannot read the history of our rise and development as a Nation without reckoning with the place the Bible has occupied in shaping the advances of the Republic. . . . Where we have been truest and most consistent in obeying its precepts we have attained the greatest measure of contentment and prosperity; where it has been to us as the words of a book that is sealed, we have faltered in our way, lost our range finders, and found our progress checked. It is well that we observe this anniversary of the first publishing of our English Bible. The time is propitious to place a fresh emphasis upon its place and worth in the economy of our life as a people.

We cannot read the history of our rise and development as a Nation without reckoning with the place the Bible has occupied in shaping the advances of the Republic. . . . Where we have been truest and most consistent in obeying its precepts we have attained the greatest measure of contentment and prosperity; where it has been to us as the words of a book that is sealed, we have faltered in our way, lost our range finders, and found our progress checked. It is well that we observe this anniversary of the first publishing of our English Bible. The time is propitious to place a fresh emphasis upon its place and worth in the economy of our life as a people.

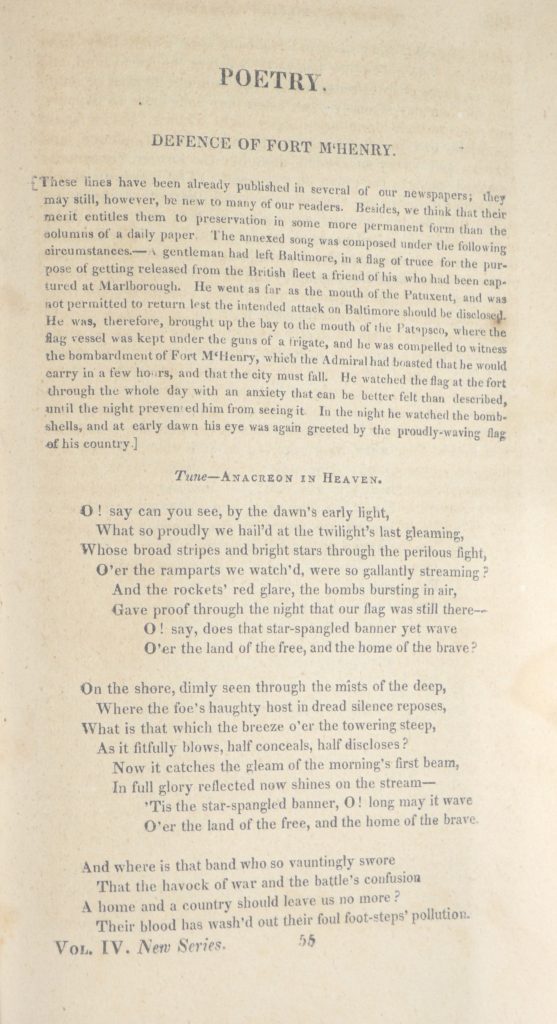

Fort McHenry had been named for Constitution signer James McHenry, who was Secretary of War under both President George Washington and President John Adams.

Fort McHenry had been named for Constitution signer James McHenry, who was Secretary of War under both President George Washington and President John Adams.

With the

With the  The rich legacy of the service and sacrifice of chaplains continued long after the American Revolution. For example,

The rich legacy of the service and sacrifice of chaplains continued long after the American Revolution. For example,

At that time, attorney

At that time, attorney

The year 1776 is well known in American history. Obviously, it is directly associated with the signing of the Declaration of Independence, but it is also the year Nathan Hale gave his life for America.

The year 1776 is well known in American history. Obviously, it is directly associated with the signing of the Declaration of Independence, but it is also the year Nathan Hale gave his life for America.  These words have inspired generations of Americans, and were regularly taught to school students. But in recent years, Nathan Hale and heroes like him have largely disappeared from American public education as well as many history books. We need to reintroduce American students (and even adults) to our forgotten heroes and thus ignite the patriotic spirit in younger generations. As children across the nation have now returned to school, help inspire a child that you know with the amazing legacy left us by those who have come before.

These words have inspired generations of Americans, and were regularly taught to school students. But in recent years, Nathan Hale and heroes like him have largely disappeared from American public education as well as many history books. We need to reintroduce American students (and even adults) to our forgotten heroes and thus ignite the patriotic spirit in younger generations. As children across the nation have now returned to school, help inspire a child that you know with the amazing legacy left us by those who have come before.