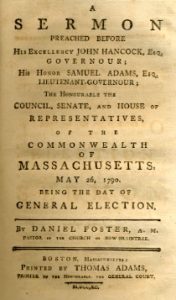

The Reverend Daniel Foster was born in 1750. He was ordained in 1788 (his father, the Rev. Isaac Foster, preached his ordination), and pastored a church in New Braintree, Massachusetts for many years. Daniel Foster had numerous sermons published, of which copies of five are know to be extant. In this election sermon, preached before Governor John Hancock, Lieutenant-Governor Samuel Adams, and both houses of the Massachusetts legislature, Rev. Foster provides an exemplary model of a pastor illuminating God’s governmental principles for the political leaders of his State. He lists the duties of magistrates as well as the duties of the people in a Christian country, and details God’s design for civil government.

The Reverend Daniel Foster was born in 1750. He was ordained in 1788 (his father, the Rev. Isaac Foster, preached his ordination), and pastored a church in New Braintree, Massachusetts for many years. Daniel Foster had numerous sermons published, of which copies of five are know to be extant. In this election sermon, preached before Governor John Hancock, Lieutenant-Governor Samuel Adams, and both houses of the Massachusetts legislature, Rev. Foster provides an exemplary model of a pastor illuminating God’s governmental principles for the political leaders of his State. He lists the duties of magistrates as well as the duties of the people in a Christian country, and details God’s design for civil government.

Reverend Foster ends his sermon by directly addressing on a personal and individual level John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and the legislators. Foster’s sermon is loaded with Biblical wisdom; and he is an excellent example of a minister whose “lips keep knowledge [that] the people should seek the law from his mouth” (Malachi 2:7).

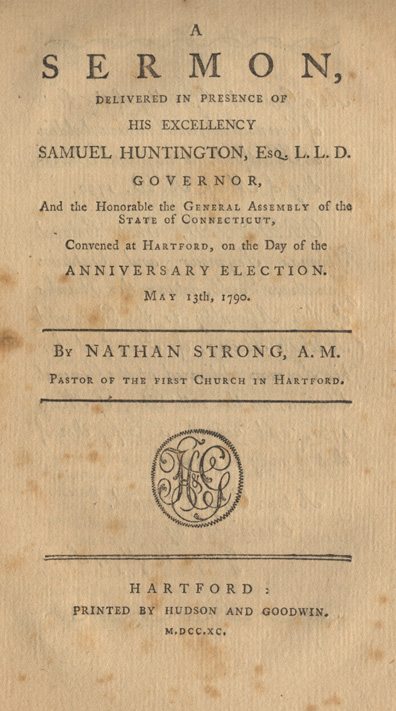

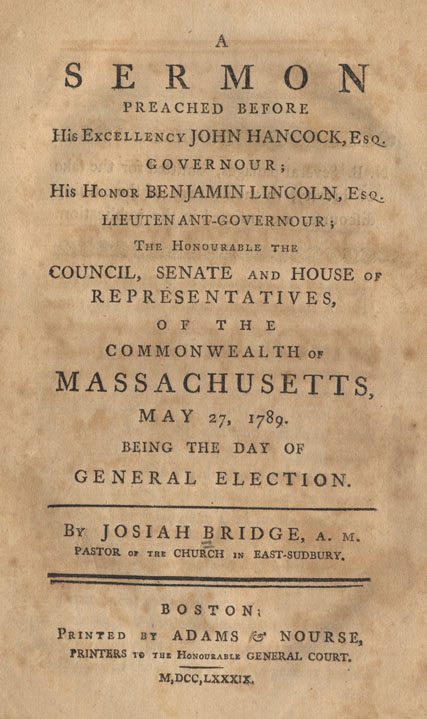

A

Sermon

Preached Before

His Excellency John Hancock, Esq.

Governor;

His Honor Samuel Adams, Esq.

Lieutenant-Governor;

The Honorable the

Council, Senate, and House of Representatives,

of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

May 26, 1790.

Being the day of

General Election

By Daniel Foster, A.M. Pastor of the Church in New Braintree.

Proverbs 8:16. By Me princes rule, and nobles, even all the judges of the earth

In compliance with the laudable example of our pious Ancestors, on such joyful anniversary occasions as this day presents us with we have assembled in the House of God, to offer our devout praises to him for what he has done for them, and for us, their children; to seek his direction and blessing upon our Political Fathers here present, in the discharge of the important trust reposed in them, and his smiles on this confederate rising Republic.

And as it has fallen to one of the least of the Ambassadors of Christ, to perform so essential a part of the exercise of the day, it will not be expected that he turn Statesman in this sacred place, or wander into all the affairs of government: But, in compliance with his character as a Minister, make such observations from the sacred text, as may be profitable for direction and encouragement, that the men of God here present, may be furnished to every good work.

This book was penned by King Solomon a man famed for wisdom and understanding throughout all the East.

That being who has an easy access to the human mind, appeared to him in Gibeon, in a vision of the night; and God said, ask what I shall give thee? And his request, “give therefore thy servant an understanding heart,” was so acceptable, that God gave him wisdom above all that were before him in Jerusalem; for the people soon perceived “that the wisdom of God was in him to do judgment.”

In these Proverbs of the wise man, we have the comprehensive duties we owe to God, and the world, made plain and easy, and enforced with the most powerful motives. By folly, the Preacher would be understood to mean vice and wickedness and by wisdom, grace and Christ.

In the text, the person speaking is doubtless Jesus Christ, who by the Apostle, is called “the wisdom of God, and the power of God.” “By me Princes rule, and Nobles, even all the Judges of the earth:” That is, by my Providence and appointment, they are advanced to rule and govern; and their government is merciful and righteous, happy and prosperous, by my council and assistance.

Ever since the apostasy; the blessed God, has pursued an uniform plan of grace, and government with the church, and the world. The merciful design of which, is to reduce to order, peace and happiness, his intelligent offspring. To prosecute this design, he has sent into the world the “PRINCE Of PEACE,” and given him a commission for acts of ministry and grace, magistracy and government.

The intervention of the new covenant, and the advent of Jesus its Mediator, gave birth to order and subordination in Heaven, and upon Earth.

In Heaven there are thrones, dominions, principalities and powers, angels and arch-angels; and upon earth, princes, nobles, and judges – and Christ is Head over them all.

The text leads us to speak of civil government, as ordained of God, in the hands of the mediator; of civil rulers, as holding their commission and authority under Christ; of their duty and dignity as his Ministers, and of the duty and privilege of the people under their administration.

I. That civil government is ordained of God in the hands of the Mediator, the Absolute necessity of order and government, for the existence and happiness of society, pleads its divine original: For without it, the affairs of mankind would fall into the utmost confusion and disorder.

The nature of man, as a sociable creature, would no doubt, have led him to some sort of government had sin never entered the world. But since sin has debased the noble nature of man, and spread itself through the whole world, both reason and revelation plead for government.

It is not a matter of human prudence only, but of necessity and moral obligation: And being enjoined by him who rules in the kingdoms of mortal men, it is an important mean of delivering us from the evils of the apostasy; and designed to prepare us for the more encouraging restraints the gospel enjoins.

Civil government, then, is a branch of the tree of life, and founded in, and built upon that covenant, sealed in Heaven by the oath of God, and upon earth by the blood of Christ.

He being commissioned by the Father to manage the great affairs of Empire, as well as of Zion.

“Yet have I set my King upon my holy Hill of Zion.” “The government shall be upon his shoulders.”

The kingdom of Christ, where he rules by his word and spirit, is his Church, a spiritual kingdom. But his commission extends to the Utmost ends of the earth.

“For the stone cut out of the mountain without hands, is to break in pieces all other kingdoms, and fill the earth.”

His kingdom will outlive all other kingdoms, and swallow them up; for he must reign till he hath “put down all rule and all authority and power.”

This implies that rule and authority among men, or which is the same thing, civil government, is a divine appointment, and that it is put into the hands of the Mediator to rule and govern the world. For when the great and important ends for which he received his mediatorial kingdom, shall be accomplished, he will put down both ministry and magistracy.

II. That civil rulers hold their commission and authority under Christ.

Not that Christ has pointed out the form of government, or the persons to rule and govern; in this sense his “kingdom is not of this world” But Christianity enforces the law of nature; and has confirmed the several constitutions of states and kingdoms, and called our obedience to the higher powers, as the gospel finds them.

The mode of government, and persons to govern, are submitted to the wisdom of men, in pursuance of a divine ordinance, that second causes might operate. It being the method of God to carry on the designs of his government in this world, by the instrumentality of subordinate Agents. When therefore, a people unite in a form of government, and choose persons to rule and govern them and pledge their faith to be obedient to, and support the government, “though it be but a man’s covenant, yet if it be confirmed, no man disannulleth or addeth thereunto.”

The Magistrate then, called to office by the voice of the people, and solemnly sworn, becomes an ordinance of God, and receives his authority from him, “by whom Princes rule, and Nobles, even all the Judges of the earth.”

And the apostle, when he enjoins obedience to civil rulers, “because the powers that be, are ordained of God,” means to include in his idea, the methods by which they become possessed of their power, and likewise the use and improvement they make of it: If they rule for God, and for good to the people, they are to be subjected to, otherwise, “we ought to obey God, rather than men.”

III. We come to speak of the duty and dignity of civil rulers, as the ministers of Christ.

1st. It is their duty to uphold the kingdom of Christ, which consists in “righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.”

Religion is, and ever has been, considered the glory of a people; as it insures the favor and protection of Heaven.

Under the former dispensation, the Ark of God, which contained his laws, was a token of his presence and defense. Governor Eli, whose heart trembled for it, sustained the tidings of the of the death of his two Sons with fortitude; but when it was told him that the Ark of God was taken, he fell and died, and his Daughter refused to be comforted, though a Son was born; because the glory was departed from Israel, and the Ark of God was taken.

Under this dispensation, the gospel and its ordinances, are our glory and defense. And as magistrates are honored by Christ, and act under his banner, they should be careful to be his glory, and support his religion in the world.

All men should be possessed of a principle of piety and virtue; but none stand in greater need of it than those who are called to rule and govern.

Religion dignifies and enables the mind “refines and purifies the heart” fits men to act worthily their part on the stage of life, and shines with a peculiar luster in the Christian magistrate. This will procure for them honor in the sight of all men; “for those that honor me, I will honor.”

Saul was destitute of this principle; but desirous of its fruits and effects. Therefore he pressed the man of God, and laid hold on the skirt of his mantle, and it rent; saying “honor me now I pray thee, before the Elders of my people.”

This is the way to have the presence, and blessing of God with them, and upon their administration.

The seat of the magistrate is called the throne of God; “and he was caught up unto God, and into his throne.” As they have the image of God upon them as his Ministers, and act by his authority, it should be their care to have the image of God within them as men.

It is an honorable account we have of Judah, in a time of general revolt, the ten tribes went after Jeroboam; but Judah yet ruleth with God, and is faithful with the saints.

If religion is not honored and supported by men in places of public trust, the glory of the Lord will soon depart, and the fire of God be scattered over the city.

Rulers are called “the shields of the earth;” they are to protect the people from injuries among men, and likewise from the judgments of God. When God’s wrath was kindled against Israel, for their idolatry at the foot of the mount, we find Moses, that pious ruler, pleading the cause of the people, and he sounds his plea upon God’s covenant, and reminds him of his oath. And David, that man after God’s own heart, when he saw the Angel that smote the people, said, but these sheep, what have they done? “And the Lord said unto the Angel, it is enough, stay now thine hand.”

The attention Christian rulers pay to religion in their hearts, and in their government, will be their support when they are called to lay down their commission, and their lives; it will brighten the scene before them, and embalm their memories when they are dead.

2d. It is the duty of Christian rulers, to preserve and secure to the people, their liberties and properties.

The end and design of civil government is to secure the happiness of the whole community. For this, rulers are appointed; “he is the Minister of God to thee for good.”

The liberties of mankind have ever been held dear, for they are given are by God and nature. “With a great sum, obtained I this freedom,” says the chief Captain to Paul, who relied, “but I was born free.”

This has been and still is the voice of Americans; and our attention to the voice, which is from Heaven, has brought us into possession of the liberties and privileges, we this day enjoy.

An infringement on these, has ever awakened the fears, and kindled the resentment of an enlightened people! It has overturned empires and kingdoms, caused the stars to fall from Heaven, and princes to walk, as at this day, like servants on the earth!

In order to secure the liberties and privileges of the people, righteous and equitable laws should be made, and preserved. “That which is altogether just shall ye follow,” is an injunction from the First Magistrate in the universe.

We plead for a government of laws, not of men. The law is a rule to try all causes between man and man by; and it is a rule between the magistrate and subject it teaches the one how to rule, and the other how to obey.

They are the pillars on which the Commonwealth stands; to them we appeal for a redress of grievances, and into their hands we are willing to fall; but not into the hands of men. They are in scripture, called the foundations of the earth; and said to be out of course, when the magistrate is either ignorant of them, or neglects to support his authority in their execution.

3d. The Christian ruler will hear the complaints, and redress the grievances of the people he governs.

He will not with Rehoboam, reject the voice of the old men whose years have taught them wisdom, and apply to young men for counsel; answer the people with grievous words, and cause them to say in the bitterness of their souls, “what portion have we in David? Neither have we inheritance in the son of Jesse.” But he will enlighten the ignorant; and those that are out of the way, he will reduce to order and obedience, with the cords of law and love. He will follow the example of him by whom he rules, whose work and glory it is, to make peace and bind up the wounds of the people.

Christian rulers will consider the infancy of the people, and the burdens laid upon them, and be careful lest they over-drive, and so destroy the flock of God.

They will lessen the charges of government, and lighten every burden, as much as is consistent with the honor and well-being of government.

The cause of the widow, the fatherless, the orphan; the soldier, and him that has loaned hi money for the help of government, will come with peculiar grace before Christian rulers; who will hold themselves Heaven’s clients to vindicate their righteous claims; and plead their cause.

The credit of the Commonwealth, at home and abroad, is a matter that requires particular attention: In many instances its faith has been pledged. But Christian rulers will remember, that our father Abraham, was not justified by faith only; and add energy to our faith, that we may as a people, be justified in the sight of God, and the world.

4th. We come as proposed, to speak of the duty and privilege of the people under the administration of Christian rulers. And

1st. It is their duty to pray for them.

Government is an important trust, and though it be limited by righteous and equitable laws; yet such is the condition of human nature in this world, that the greatest and best of men are liable to err, and are insufficient to manage the great affairs of state, without direction and influence from Heaven.

God is the blessed and only potentate, his essential perfections are his blessedness, and enable him to manage an universal Empire! He stands in no need of his creatures’ wealth to maintain his crown, their power to effect his designs, or their wisdom to direct his counsels. But it is far otherwise with his vicegerents here on earth; though they are called gods, and clothed with authority from Christ and the people yet they are but men.

The affairs of government are often intricate and perplexing, and dangers eminent and threatening, so that rulers find occasion to adopt the language of the pious king of Judah, “neither know we what to do.”

We are divinely bound to pray “for all in authority,” that government might be equal and righteous, and that we might “lead a peaceable and quiet life, in all Godliness and honesty.”

It is the blessing of God, that makes government steady and effectual, and gives peace and quietness to the Commonwealth; and God will be sought unto, for such an inestimable blessing.

When we pray for them, we pray for the advancement of peace, and Godliness, this being the end for which government is instituted.

2d. It is the duty of the people, to support their rulers. That authority by which they govern, enjoins obedience from the people to all their righteous laws.

And as they have a painful preeminence above their fellow mortals, and an arduous and important trust committed to them by God, and the people; they should be freed from cares and troubles about the affairs of the world. “For this cause, pay you tribute also; for they are God’s Ministers, attending continually upon this very thing.” The advantages we enjoy tinder a righteous administration, entitle those who govern to large returns. Our persons and properties are secured, and we set under our own vine and fig-tree; being protected, by a government merciful and righteous.

When taxes are made for the support of government, there is a moral obligation on the people, to discharge them; for government which is an ordinance of God, could not subsist without such support.

Our blessed Lord set us an example worthy of imitation, when he sent Peter to the mouth of the fish, that he might receive money to pay their tribute. And enjoined upon us to “render to Caesar, the things that be Caesar’s.” A support, honor, love and obedience, are enjoined through the whole book of God, upon the people, as a just tribute due to those who govern.

It is the privilege of the people granted them by God and nature, to choose their own rulers.

Kingly government was never of divine appointment; but added, as the law was, “by reason of transgression.”

The government, early established in the world among the ancient Hebrews, was a free republic like ours, the sovereignty resided in the body of the people.

They were to choose able men; and they were called to give their assent to the laws given from Heaven, before they were put into execution.

When government is thus founded, according to the divine mind, and rulers chosen, they become representatives of the power and majesty of God; and important instruments employed by his providence and grace, in the administration of affairs in this lower world.

They are entrusted with the lives, liberties and properties of the people, For them prayer should be continually made, and to them obedience given, as God’s vicegerents, when they rule for him, and for good to the people.

People should be careful of censuring them, and increasing their burden and concern, lest they be reproved by him, who has forbid our “reviling the gods, or speaking evil of the rulers of the people.”

But when rulers neglect the great affairs of government “when they break not every yoke” plead not the cause of the injured and innocent, the widow and fatherless, the poor and needy, when they do not support religion, liberty, the arts and literature; the pillars of government will fall, and society throw off its pleasing apparel: “The sword shall be upon the arm, and upon the right eye of the magistrate” he shall lose his discernment in public measures, and his authority shall be taken away.

On the other hand when those in authority, move with dignity in their proper sphere, are God’s ministers for good; and people are subject for conscience sake, what a pleasing appearance does the Commonwealth put on! Such as once induced the prophet to exclaim “how goodly are thy tents, 0 Jacob, and thy tabernacles 0 Israel!”

From what has been said we may infer.

1st. That God in the scheme of grace by Christ, provided for the happiness of mankind in this world, as well as for their immortality and glory in the next. And foreseeing to what endless confusion and irregularity the world would tumble, without order and subordination: has with one stroke wrote himself, religion and government on the mind of man. – And has sent his son from Heaven to explain, and enforce, what, at first, he wrote on the mind of man, and to reign and govern in righteousness.

Civil government is designed to sub-serve the grace of the gospel; and the happiness it defuses through society in this world, should call forth our gratitude and praise to God, its author.

It smoothes the rugged road of life, gives the quiet and peaceable enjoyment of every blessing, and raises in the mind, the most exalted conceptions of that blessed Being, whose benevolent design, is to raise the virtuous among mankind, by small gradations, to happiness and perfection with himself.

Government is a link in the chain of everlasting mercy; and those who are obedient “for the Lord’s sake” who has appointed it, may expect that their path will shine more and more unto the perfect day.

2d. We infer. “That days of greater peace and happiness, then have ever dawned upon the church and world and before us in America” this we argue from the ability of Christ’s person, the extent of his commission, his going forth of old with our fathers; and the deliverance he hath wrought for this generation.

The kingdom of providence, and the kingdom of grace are his; and he manages the affairs of the one in subserviency to the other.

It has been the method of God from the beginning, to reveal the designs of his grace and mercy to the world by degrees.

He promised one, mighty to save, and able to govern soon after the apostasy in the garden; but four thousand years were numbered, before the desire of all nations came.

Since he appeared on the theater of life, the church and world have pressed on for ages, through, the fire of perfection: Deluges of blood, oppression and slaughter, but little benefited, to appearance, by his coming and death.

Till the Angel of the Lord pointed our forefathers to this Western World; a land where he determined to unfold the plan of redemption and government. Here they found a safe retreat from persecution and cruelty. Savage beasts and men vanished before them, like the dew before the rising sun.

Here the church was founded upon the doctrines of Christ, and the Apostles, which put forth her branches like the palm-tree, and bid fair to eclipse the glory of the world.

This awakened the fears of the country from whence they came, who were grieved at our greatness and envious at our rising glory, and attempted to take from us, our liberty, and this land God gave to our fathers; prepared chains to bind us to passive obedience, and drag us to perdition. The great charter was violated, and the laws that were to protect this infant world, infringed upon. “The foundations were all destroyed, and what could the righteous do?”

In that day of our distress, we appealed to the strength of Jehovah, and the justice of our cause: And God came from Teman, and the Holy One from Mount Paran, he stood and measured the earth, and drove asunder the nations, and confirmed us in the possession of this goodly land.

Under the direction, and by the assistance of Him, who administers on Heaven’s eternal plan, we are delivered from the horrors of war, and enjoy both civil and religious liberty!

We have been led to frame and adopt a constitution of government that is the wonder of the world; resembling that which God of old, gave the Israelites, the seed of Abraham his friend.

We shouted with heartfelt joy, when the political ark was brought to its place. Sing O Heavens for the Lord hath redeemed New England, and glorified himself in America!

When we look over these great events, we are constrained to cry out with the Patriarch, “surely the Lord is in this place, and we know it not.”

We are respected abroad among the nations of the earth, and united at home. God has put this honor upon us, and spoke peace to our borders.

The system of national government we have settled, we hope, will secure to us, and hand down to the generations to come, the liberties and privileges we have procured by our toil, treasures, and the blood of many of our virtuous sons.

The choicest blessings, religion, liberty and peace, were reserved in the counsels of God, for thee, O America!

And what God has done for our fathers, and for us of this generation, are but intimations of our future happiness and glory; that he will have a light before him in this Jerusalem, ’till the second coming of Him, who is the “light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of his people Israel.” Here the empire of Jesus is founded, and these are the halcyon days disclosed to the pious Prophet, in a vision of the night.

“And behold! one like the Son of Man came to the ancient of days, and there was given him dominion, glory and a kingdom; and his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away; and his kingdom, that, which shall not be destroyed.”

From the rise and present exaltation of America, we conclude she is to be the theater, where the latter day glory shall be displayed; and the medium through which religion, liberty and learning, shall be handed round creation.

3d. We infer: That Christ will vindicate the sacred rights of his government, in the utter destruction of all that oppose his reign.

It becomes rulers, ministers and people, to be willing subjects of this kingdom, that they may be the glory of Christ its King.

The impious and ungodly will be ensnared in their own plots and devises; and the Heavens will reveal their iniquity one day. “Kiss the Son, less he be angry, and ye perish from the way.”

True it is, God has done great things for us; he has delivered us from war, and invited us by the dawn of peace, to lay aside the dread artillery of death; he has given us a land that flows with milk and honey, and settled both church and state in peace.

But what is this to the sinners of my people, who live in intemperance, debauchery, pride and luxury, fraud and deceit; who violate God’s holy laws, neglect the duties of the gospel covenant, cast off fear, and restrain prayer before God.

Jesus, who is exalted at the head of the universal polity of Angels and men, when his wrath is kindled but a little, will dash such characters to pieces like a potter’s earthen vessel.

From the evil returns we have made to Heaven for past mercies, we have reason to fear the divine rebukes: “You only have I known of all the families of the earth, therefore I will punish you for your iniquities.

God brought his people of old to the borders of the promised land; but they murmured against Moses and Aaron, and were for making a Captain and returning into Egypt. This provoked Him who had done great things for them, to say “your carcasses shall fall in the wilderness, and ye shall know my breach of promise: But your little ones, them will I bring in, and they shall know the land which ye have despised.” So it will be with the wicked of this generation; with Balaam we behold the glory of America, but not nigh; we shall meet the grave, and the horrors of eternity; and our “sons will come to honor, and we know it not.”

We have solemn tidings this day from the mount of God: “The children of New England have forsaken my covenant: Do ye thus requite the Lord?” O foolish people and unwise!

Hear with what irresistible eloquence the prophet Isaiah pleads against the impenitent of this age and country; “Hear O Heavens, and give ear O Earth, for I have nourished and brought up children, and they have rebelled against me.”

O that we may as a people, know in this our day, the things of our peace, repent, and do our first works; that God may heal us, and bestow those blessings, he has encouraged us to hope for, from past mercies. Then shall we find the grave in peace, and leave this inheritance to our children’s children; who will read the history of our day, with amazement and veneration, and call us blessed, when we are sleeping in the dust!

But it is time that I close the subject with particular attention to the important political characters that compose so great a part of this respectable assembly.

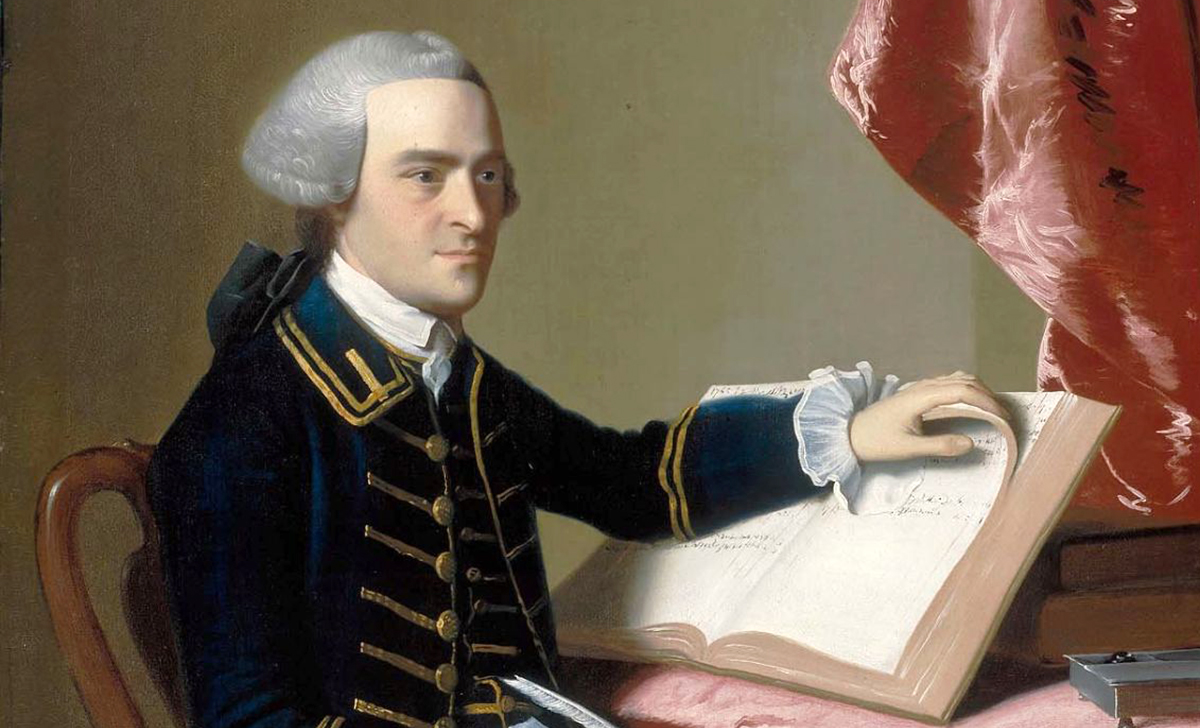

And His Excellency the Governor and Commander in Chief of this Commonwealth, claims our first attention.

MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY,

We rejoice to find, venerable sir, that you are again, by the suffrages of a free and independent State, called to fill the first seat of government. You are the man on whom the eyes of this Israel are set, that you should rule over us.

Your former services for these States, in the day of small things, and your administration government in this Commonwealth, are engraven on our hearts, as with the point of a diamond.

It was under your presidency and direction, that an ancient prophesy was literally accomplished, “a nation born in a day.” America declared free, sovereign and independent!

Your ardent love to your country, your indefatigable labor on her behalf, and your alms which have been distributed to the poor and needy, render you dear to this, and will, to the generations to come.

Time shall stop her course, and expire in eternity, before you will be forgotten. While religion, liberty, justice and benevolence, are counted valuable upon earth, your Excellency will have a name and praise in it.

An holy God has deprived you, of a promising son to bear up your name, when you become weak like other men, and are called to sleep with your fathers, and by him, who for so many years, was your worthy and pious contemporary in office: But he has left you a name better than that of many sons; one that will live in the breasts of virtuous Republicans, ’till our father Adam shall salute the arrival of his youngest son to the abodes of bliss.

We have not only a grateful remembrance of your past services for America, and this Commonwealth in particular, but we confide in your good disposition, and uncommon abilities, to fill with dignity, the seat of government, where Divine Providence has placed you.

Your Excellency will please to remember, that your authority comes from Christ, though by the mediation of the people; whose religion you will imbibe in your heart, and support in your government, that the people may take knowledge of you, that you have been with Him, by whom you rule.

The ministers of Christ, who are commissioned by the same authority that invests you, will meet your countenance and protection, though they act in another apartment in the house of Christ.

The University, that has given birth to so many important characters, both in church and state, leans forward, as it were, and whispers to you her son, to administer to her necessities.

We wish you the presence and blessing of Heaven, to enable you to act in your whole administration, under the influence of a principle of justice and mercy: This will entitle you to the love and esteem of a people you have made happy. This will yield you calmness of mind, under the bodily infirmities, God is pleased to inflict you with, and the cares and troubles of government, this will brighten the gloom of death, and give you boldness in the day of Christ.

May you long live to serve your God and generation; and when you are called to put off this mortal form, may your soul wing her way to yonder bright and intellectual world; where, from the mouth of your Divine Master, may you hear that blessed euge, “well done good and faithful servant, thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things, enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.”

His Honor the Lieutenant Governor, claims our next respects, to whom the discourse is now addressed:

MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOR,

It has pleased God to spare your important life, to see the fruit of your labor and anxiety, in years past, and to awaken the attention of the people to call upon you, to exert your talents and abilities for the good of this Commonwealth, At a time when the voice of men, whose years have taught them, is needed.

Your integrity, patriotism and devotedness to the cause of your country, has given you favor, and kindled in the minds of the people esteem and veneration, that time will not obliterate.

The Recording Angle will not silently pass by your labor and attention, when we came over Jordan with our staff.

The laws of justice and gratitude, which are the laws of God, require that we accept it with thankfulness to you; and more especially to that God, who has made you so instrumental in delivering us from tyranny and oppressive power.

We have a recent remembrance of the critical day, when His Excellency and your Honor, were excluded a pardon of God and America, for their insults and cruelty.

You have lived to see your desires accomplished; the Temple of Liberty raised and the glory of America, founded through the world by the trump of Fame! Now your eyes behold this, you are ready to adopt the words of Simeon, when he clasped the infant Savior in his arms, “now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, for I have seen thy salvation.”

We look to you, honored sir, and expect that you conspire with your best endeavors, to make easy and happy, this great people: And may a grateful people, by their returns of honor and justice, equal your past, and their expectations of your future services.

May God have you in his holy keeping; make the remainder of your days comfortable and happy, and when he shall see fit to discharge you from further services below, may you shine forth with resplendent glory in the kingdom of the Redeemer above.

And may the Honorable Council, so necessary and important a Branch in government, be counseled and directed of God; and in all matters that come before them, act with stability and firmness, being influenced by that wisdom which is from above.

May your piety and virtue, gentlemen, recommend you to the favor and protection of Heaven; and your integrity and uprightness of conduct, render you more and more objects of the love and confidence of your brethren. But if your labor and fidelity, should not meet the approbation of the world, as it is often the case, you will have within you, conscious worth before you, an animating prospect of the acceptance of God, and a reward in the world to come.

The Honorable the Senate, and the Honorable the House of Representatives, claim the attention of the Preacher, and to whom he would now turn his discourse.

You are this day, respectable gentleman, constituted the ordinance of God, for good; and, having received authority from Christ, and the people, you have before you a very weighty concern, to promote the best interest of the people, and see that the Commonwealth receive no detriment.

The multitude of your brethren have put confidence in you, and made you the keepers of their vineyard. You will regard, gentlemen, the sacred enclosure of Christ, and be nursing fathers to his church, and people. We look to you for equal and righteous laws, and a pattern of every virtue.

You will remember, that government came into the world, on the same benevolent errand its Divine Author did, not to perplex and destroy men’s lives, but to enlighten, reform, and save them: And if there are any laws too sanguine in the case of life and death, you will adopt some other punishment than that of sending souls unprepared, to the tribunal of God.

Be not unmindful, sirs, that the eyes of God are upon you in your public capacity: He observes what attention you pay to the concerns of the public, to the widow and fatherless, the poor and needy, and the cause of virtue and religion. To him you are accountable, and before his awful tribunal you must soon stand, with the meanest of your brethren.

You are called Gods, let your compassion to the poor, resemble that of the Father of Mercies.

Guard against pride, covetousness, and a disposition to bind heavy burdens on the people.

Lay aside party considerations and private designs, and do that which you can answer to God, and the people. Then you will be blessed and the blessings of many, ready to perish, will come upon you. And in the last grand revolution, when all distinctions, but those of a religious nature will be forever done away, you will meet the approbation of HIM, by whom you rule, and your reward will be great. We wish you divine direction, and a blessing, this day, out of the house of God.

Let this great and attentive Assembly, call to mind the duties they owe to God, and the world, and the obligations they are under to the faithful discharge of them.

Of infinite importance is it to us, Christian friend’s, that we are possessed of that faith in, and faithfulness to Christ, which the gospel constitution makes necessary, in order for us to obtain eternal life. If we are the subjects of divine grace, and act worthily our part on the stage of life, we may meet adversity with fortitude, and death with comfort – for it will reach us to a world, where God will be the sun, in which he will run through our souls with a torrent of delight. On this pleasing hope and joyful expectation, I will dismiss you, until that day, in which may the Preacher find mercy, and meet you all amongst the redeemed of the LORD – and the glory shall be given to HIM, who sitteth upon the throne, and to the LAMB, forever and ever; and let all the people say AMEN