An

Oration

On the Occasion

Of the National Fast;

Delivered Before The

Academy of Sacred Music,

In the Broadway Tabernacle, New York,

On Friday Evening, May 14, 1841.

New York:

Office of the Iris, 647 Broadway,

John S. Taylor & Co., 145 Nassau Street.

1841.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1841,

By George H. Houghton,

In the Clerks Office of the District Court of the Southern District of New York.

Piercy & Reed, Printers, 9 Spruce St.

Advertisement

The introductory remarks of this Address have reference to two things which may be here more distinctly presented. The one is, those widely-circulated notices of the meeting, on the evening of the Fast Day, which were intended to indicate the subject of the Address. This is their form: “Rev. E. N. Kirk will deliver an Eulogy on the Death of the late President Harrison.” These notices are alluded to here, both because of the blunder they contain, and for the wrong impression they were calculated to make. The author of the Oration is not responsible for their awkward use of language, in speaking of an Eulogy on Death, where they meant to promise an Eulogy on the President. And moreover, although the personal qualities of that great and good man are incidentally introduced, yet the discourse was in no way designed to be, nor, we think, can it properly be designated, an Eulogy. The other allusion is to the fears of many excellent persons, that the Academy of Sacred Music would give a secular character to the latter part of a day designed to be as sacred as the Sabbath. Nothing was farther from their desires, nor from those of the speaker. Whether the fears were well or ill-founded, must be determined by those who heard, and by those who now may read.

E.N.K.

Address

The specialty of the case may justify a preliminary remark. Many who desire to see this day and its rites so observed as to meet the Divine approbation, and secure the greatest degree of the Divine blessing, have feared that the present exercise might strike and discordant not, and disturb the plaintive harmony of the nation’s dirge. It is of course manifest that we do not participate in this fear. Nor should it be alluded to here, did it not furnish us a good occasion for introducing the fact, that the general estimate of Sacred Music is too low. If the fear is founded upon the notice that there was to be a Concert and an Eulogy on the Death of General Harrison, we are not surprised at it. A Concert given in reality for the public amusement, but calling itself “sacred,” were as ill-timed and sacrilegious, as it were unfair toward those places of professedly secular amusement, which, in deference to public sentiment, have this night closed their doors.

And again; it were as much a violation of good taste, as of religious propriety, to devote the hours of such a day to an “Eulogy on Death,” as your advertisements have it, or an Eulogy on our departed chieftain, as your advertisements partly state and partly imply.

And yet again; if he, who knows not this Academy, nor its principles, aims, and practice, presumes that its members are not acquainted with the true nature of Sacred Music, and its relations to such occasions as the present, and therefore fears that the holy art will be perverted, and the holy season desecrated, we need no other vindication than the exercises of this evening.

But if the fear alluded to, implies that Sacred Music should not occupy the hours of such a day, then we must be indulged in our brief plea. And it is altogether based upon this fact, that the elements of Sacred Music; sacred poetry expressed by appropriate melody and harmony, have not on earth a more appropriate sphere than that which we here assign them.

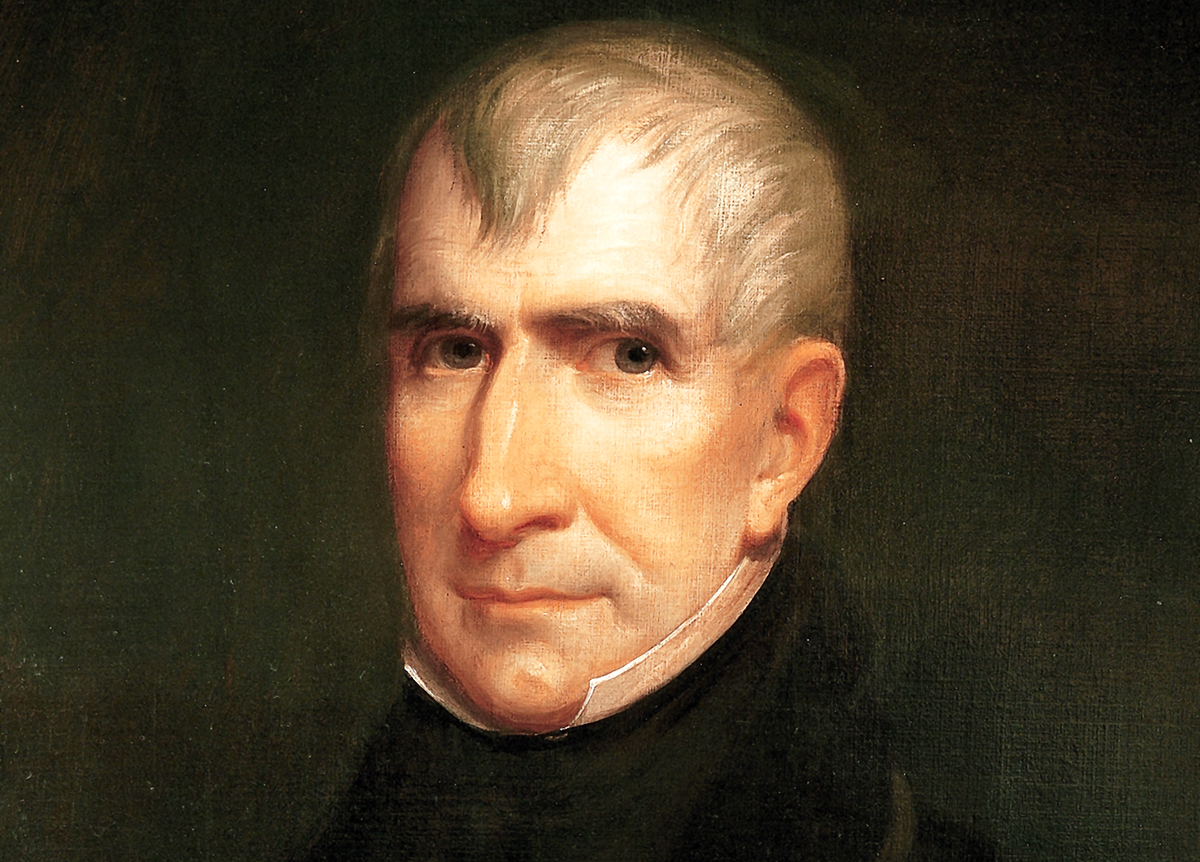

A nation is mourning its bereavement in mutual condolence! A nation is mourning its sins in lowly prostration before the offended Deity! The active stir of business is suspended, the voice of mirth is hushed, the face of beauty is veiled, the steps of millions hasten tremblingly to the house of prayer – the honorable and the base are gathered in the temples of mercy – ten thousand supplicating voices are raising their imploring cry, “Spare, O Lord, thy people; give not thy heritage to reproach” – the strength of the nation is feebleness before God, lofty looks are bowed, and proud spirits are contrite – intellect, the heart, the will of a free and mighty people lies low before the mighty Governor of the Universe. He has taken away our staff and our strength; He has removed the stay in which we trusted; and thus cast the nation upon his own naked arm; and we are made to feel an awful nearness to the Omnipotent. He has taken away the veil which hid Him and His authority from our unbelieving eyes; and a sinful people seem to be ushered unanointed into the presence where angels tremble, and archangels veil their faces! Well may we weep. We do weep. The voice of lamentation is wafted like the sigh of the summer wind from the Northern Lakes to the Southern Gulf, from the Atlantic Sea to the Rocky Mountains. It is in the presence of Death we are weeping. We had but just rejoiced as a nation. Part of us had honestly opposed the choice; but the choice once made, patriotism carried it over party, and the man of the North West became the man of the country. Never since the first days of the republic, had there been such enthusiasm on the accession of a Chief Magistrate. The heart of the people has honestly, profoundly glad; but scarcely had the excessive, nay, the idolatrous congratulations ceased, ere the whisper of fear began to spread; the sun had barely lifted his cheering disk upon our horizon, ere a dark cloud was drawn toward it by a mighty and invisible hand. The people trembled, they supplicated; but the decree had gone forth; the mercy that would save us from total ruin, arrested us kindly, though sternly; it gathered us around a vacated throne, a pallid corpse, a silent grace, and changed the voice of joy into lamentation; that amid blasted hopes and broken hearts, we might pause to “hear the voice of the rod and him who appointed it.”

Death is always formidable to man as an inhabiter of time and an inheritor of this lovely planet, so full of God’s bounty. We are loth to part from familiar scenes; we are by instinct tenacious of life. And when we see any fellow-creature die, we start as from a spectral hand that writes our own doom. But when death strikes a high mark; when it treads unrelenting upon hopes and hearts, breaks through the life guard of the throne, and despises the supplicating millions; our terror is enhanced. It has entered our palace; it has conquered our unvanquished defender; it has dimmed the eye that watched only for his country’s welfare; it has closed the ear that was quick to a nation’s complaint, and open to the cry of the needy; it has chilled the heart that throbbed with paternal love over the people that called him father; it has palsied that hand, so honestly, so honorably pledged to defend the Constitution, and to execute the laws. As was said of the death of the great Maccabeus, so may we say here: “At the first tidings of this dreadful accident, all the cities of Judah were moved, streams of tears flowed from the eyes of all their inhabitants. They were struck for a time, dumb, immoveable. An effort of grief at length breaking this long and sad silence, with a voice interrupted by sobbings, that sadness, pity and fear are wringing from their hearts, they exclaimed, ‘How is this mighty fallen, he who saved the people of Israel!’ At these cries Jerusalem redoubled her wailings; the vaults of the temple trembled, the Jordan was troubled, and all its banks echoed the sound of these mournful words: ‘How is the mighty fallen, that saved the people of Israel.’”

Yes, the nation feels; and to express her feeling, behold this day of fasting and prayer! Yes, America, “Atheistical America,” who has no national church, no national creed, no national clergy; America is now in the dust before her God. To our friends and to our foes in Europe, who ask, Where is your religion? We reply, Behold it! With you it may be form the state policy to appoint and observe a fast. But with us, none can doubt that it is a genuine expression of public sentiment. Here is no pageant, no pomp, no royal patronage to encourage our piety. It is a free people invited by a man who has and who wishes no other authority than such as the people have given him, to meet the chastisement of our common Father. And we have done it. We have done it, because we recognized that God has afflicted us, and that for our sins. Such is the object of this day and of its exercises. But what can more appropriately enter into the design of this day, than penitential song? It is answer enough to this, to refer to the dirges and elegies of Jeremiah and David. Whether then we contemplate this fast as an expression of true grief or as an act of homage and worship toward a God holy, and yet inclined to forgive the penitent; Sacred Music is a most desirable auxiliary in our solemn public exercises.

But we leave the vindication, and enter more directly upon the designs of this day. In the expressive language of the prophet, we have paused to “hear the rod and him who hath appointed it.” This day has reference to the past and the future. The rod is upon us, and it speaks to us of the sins which is rebukes; and it hath another voice, lessons are rich, varied, most important, nay, indispensable. America, O America! My dear, my native land, hear the voice of the Lord! Americans, my countrymen, shall we not hear this voice; shall we fail to profit by these lessons? Shall we not become better observers of Providence, and commune more closely with Him “in whom we live and move, and have our being?”

The Voice of the Rod

1. We are learning our dependence on God. Nation after nation, for nearly six thousand years, has been trying to obtain prosperity independently of the favor of Jehovah. The experiment has been fairly made; made under every variety of circumstances. But no one nation has ever yet truly prospered, and answered the true and obvious ends of the social state; because no nation, not even the Jewish, has yet governed itself permanently and faithfully by the will, and under the supreme authority of Jehovah. And hence the most of them have run a career of ambition, crime, and luxury, to dreadful and utter ruin; while others have remained in a state of stagnant, though sometimes splendid barbarism. America sees the open page of history spread before her. Infidelity and Christianity are both expounding it to here, each in its own way. The one says– no, it was simply and solely because they cast off the fear of God.

The political and diplomatic errors which led immediately to their destruction, had their origin in national impiety. The universe waits to see to which Instructor the young republic will accord its faith. Untold and unborn millions await this decision. The exercises of this day ministers of Christ feel as they do feel, their souls pressed with unusual responsibilities. May the Spirit of the Lord be our aid.

The holy oracles proclaim that Jehovah ruleth among the armies of heaven, and doeth his pleasure among the inhabitants of the earth; that it is he who lifts up, and he who casts down. This was believed by our fathers. But the Atheism of the European illuminati rolled its pernicious waves over us soon after the revolution; and we have had many manifestations of that Skepticism which denies to the Son of God the supreme control of human affairs. What, through our dullness, the sacred oracles failed to teach, He has been teaching by the rod of His chastisement. And the lessons have not been in vain.

I select a single specimen of the tone of the secular press in our country, in reference to this fast; a tone to us full of promise for our country:

“National Fast.– We hope to see evidence that the occasion of the National Fast will not have passed by as a mere formality. We hope to see proofs that the National Heart can be touched by the spirit of devotion.

“It is nearly time that this and other Nations, professing to be Christian, should break some of the links in the base chain that binds them to the foot-stool of Belial, Moloch and Mammon. The spirit of avarice especially should be crushed. It is in this country a whirlpool that is engulphing all, with hardly an exception. The base pursuit of gain, with little regard to the honesty of the means, has become the disgrace of some of those most eminent for intellect, and heretofore highest in public estimation.

“We hope that by divine co-operation the hearts of our countrymen will be ‘touched to finer issues.’ For we are sure that a mere money-loving and money-seeking nation, must sink under the enervating indulgences, which the sordid spirit brings in its train.”

“Then look at the frequency with which the most enormous crimes are perpetrated; the frauds, embezzlements, defalcations, and forgeries, which greet our ears on every side; the prevalence of Sabbath-breaking, intemperance and profaneness, (though in these particulars we hope there has been some amelioration of late.) Look too at the delicate sate of foreign relations. How easily, by an unfortunate turn of affairs, –by the occurrence of some ‘untoward’ event, –may we become involved in a bloody and protracted war! Now these accidents, as we call them, are entirely within the control of the Being before whom if, as individuals, we look at our personal demerit in the sight of the Holy One, surely, taking all these things into account, and a thousand more which will suggest themselves to the reflecting mind, we shall find reason enough for setting apart, as a nation, one day for fasting, humiliation, and prayer.”

From the Spring of 1837 to the present day, there has been a powerful tendency of the public mind back toward the recognition of a minutely superintending Providence Events which human prudence would not foresee nor provide against, indicated the movings of an invisible hand, and suggested the counsellings of a Superior Will; blow followed blow, cloud came after cloud, until the close of the last political campaign. Then hope revived; and confidence was returning. The country had chosen a tried man, a man whom his enemies opposed, not from personal, but political considerations; who had, in fact, no enemies but such as envy made. There he sat, calm at the helm, inspiring new confidence in our institutions, new hopes for our country. The Lord saw it, and saw that we had not yet learned where to put our trust. And again; the pressure of his hand must be felt. The rod is therefore upon us. It teaches us, that while political sagacity has its sphere, and that a very important one; yet, after all, there remains so many occult which modify and baffle all his plans and enterprises, that man in his very philosophy ought to seek for a sure director of those unseen influences, those hidden but mighty powers, determine the fate of empires. My countrymen – God is teaching us that He reigns over us, that his favor is life. We must learn that lesson, or perish. We must learn to recognize, to fear, to obey, to trust, to supplicate God, who has revealed himself in his Word. We had in the late President all that we can ask in a Chief Magistrate of a Constitutional Government. He met the wants of our hearts as well as those of our judgments; and therefore we loved as well as trusted him. Probably there is scarcely the man living who combines, both in his history and character, so many of the qualifications that office requires. He was evidently fitted of God for the station and its responsible duties. He had the practical talents for governing, which are more needed there than in any other office of the republic. All this has been proved by incontestable evidence. Through a space of at least twenty years, he was called upon to act in the varied character of Commissioner to the Indians, Secretary of the Territory, Legislator, Commander in Chief, and Governor. Here he displayed all those practical talents, that purity of purpose, that knowledge of men, of public affairs, of the principles of government, which his last station demands. He had, in fact been remarkably trained amid the horrors of the border- warfare, the difficulties of treating with the treacherous savage, and the rude settler. But as he rose from station to station, he became more and more the very shield and pillar of that whole North- Western Territory. By treaty he procured the right of the soil, by the prowess of his arm he defended it, by the wisdom of his counsels he governed it. There were times when the Indians renewed their bloody system of border-warfare. Once, shortly after the battle of Tippecanoe, they commenced their depredations on the borders of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, at points so far distant from each other, as to distract public attention and create a universal panic. As the murders became more frequent, and more aggravated by the cruelties which attended their perpetration, the alarm scene of dismay and suffering; the labors of husbandry were suspended, families deserted their homes and sought safety in flight, and Governor Harrison found himself surrounded by fugitives claiming protection, and by sufferers demanding vengeance. There his patriotism and capacity and energy were called into full exercise. The country was put into the best posture for defense, the enemy was met at every point where his approach could be anticipated, and the defenseless inhabitants owed their safety, under God, to his well directed energies. Of his integrity, it is enough to state, that after having had more power than many an eastern prince, over men’s persons and property, more opportunity to enrich himself in appropriating the best lands of the world; by one treaty alone, securing fifty-one million acres of the richest country in the West, and the most valuable mineral region in the Union, he lived and died poor, and that not from prodigality, but integrity. He never used his immense power and influence to procure stations for his own relatives, if we except his private Secretary. And soon after his resignation in the army, while the wants of a large family were pressing upon him, he made up his mind to ask an appointment for one of his sons in West Point. But before he had done it, a poor boy, a neighbor’s child, made a personal application to the General, to secure him a place in the Institution. He immediately waived the application for his son, and procured a place for this poor lad, who is now a distinguished citizen of Indiana. Who can doubt the integrity of that man! Equally strong was his sense of honor, which was to the country a pledge that merit, and not favoritism nor party-interests, would secure the places of trust. A political opponent, who had known him for forty years, said: “General Harrison never had a particle of dishonesty about him; he was honest in politics, honest in religion, honest in everything.” His benevolence which is the antagonist of ambition. There has been much reproach cast upon our government in regard to the Indians; but he who becomes familiar with General Harrison’s history, will not make the charge of cruelty without many and strong qualifications. Harrison was a warrior; and there may have been a mingling of that selfish love of military renown which leads many to enlist cheerfully in the work of blood. But every step of his military career indicates the contrary in his case. Let the historian speak here for a moment: “On the morning of the 27t, the final embarkation of the army on Lake Erie, commenced. The sun shone in all his autumnal beauty, and a gently breeze hastened onward the ships to that shore, on which , it was anticipated, the banner of our country would have to be planted amid the thunder of British arms and the yells of ferocious Indians. While moving over the bosom of the lake–every eye enchanted with the magnificence of the scene, and every heart panting for the coming opportunity of avenging their country’s wrongs, –the beloved commander-in-chief caused the following address to be delivered to his army:

‘The General entreats his brave troops to remember that they are the sons of sires whose fame is immortal; that they are to fight for the rights of their insulted country, while their opponents combat for the unjust pretensions of a master. Kentuckians! Remember the river Raisen; but remember it only, whilst victory is suspended. The revenge of a soldier cannot be gratified upon a fallen enemy.’” The latter sentiment characterized all his military operations, even with the savage tribes. He never drew his sword but for his country and for liberty. It was fiery rampart to our exposed frontier; but it blazed only for defense. And in alluding to his qualifications, we speak once more of his simplicity of character and manner. One who knew him wells, says: “in personal address and manners, he was the very man to be popular in a republican government. He was no aristocrat in democratic disguise; but, a people’s man, he went among the people in the people’s dress, and with the people’s manners. Though President of the United States, any one could see him even from sunrise in the morning. He had a native courteousness united with the ease and dignity of a Virginia republican. His countenance was goodness, honesty, frankness, and disinterestedness. His eye was emphatically “the light of his body,” a soft, sparkling eye–dark, but gently; and though gentle, full of fire. Mildness and energy were hardly ever more beautifully blended.” Another says, “he was condescending. The poor and illiterate found as ready access to him as the great and learned. Even the children were at home with him, and none but the guilty were embarrassed in his presence.” His views of agriculture, as presented in an address delivered ten years ago, are so entirely accordant with the spirit of our institutions, so utterly opposed to this office-seeking, money-grasping spirit, that now infects the youth of our nation; and at the same time these views are so strongly descriptive of the simplicity and purity of his character, that you will bear their introduction here. “The encouragement of agriculture, gentlemen, would be praiseworthy in any country; in our own it is peculiarly so. Not only to multiply the means and enjoyments of life but as giving greater stability and security to our political institutions. In all ages and in all countries, it has been observed, that the cultivators of the soil, are those who were least willing to part with their rights, and submit themselves to the will of a master. I have no doubt, also that a taste of agricultural pursuits, is the best means of disciplining the ambition of those daring spirits, who occasionally spring up in the world, for good or for evil, to defend or to destroy the liberties of their fellow-men, as the principles received from education or circumstances may tend. As long as the leaders of the Roman armies were taken from the plough, to the plough they were willing to return. Never in the character of General, forgetting the duties of the citizen, and ever ready to exchange the sword and the triumphal purple, for the homely vestments of the husbandman.

The history of that far-famed republic is full of instances of this kind; but none more remarkable than our own age and country have produced. The fascinations of power and the trappings of command were as much despised, and the enjoyment of rural scenes and rural employments as highly prized, by our Washington, as by Cincinnatus or Regulus. At the close of his glorious military career, he says, ‘I am preparing to return to that domestic retirement, which, it is well known, I left with the deepest regret, and for which I have not ceased to sigh through a long and painful absence. Your efforts, gentlemen, to diffuse a taste for agriculture amongst men of all descriptions and professions, may produce results more important than increasing the means of subsistence, and the enjoyments of life. It may cause some future conqueror for his country, to end his career,

“Guiltless of his country’s blood.”

Such views in our day are of incalculable importance and you will excuse their introduction while I am showing what we have lost, in losing such a man. And you will allow one other feature of his character to be mentioned; his patriotism. He was born of a race that have distinguished themselves as lovers of liberty. As far back as Charles I, we find a Harrison, boldly condemning to the scaffold a monarch who as much violated the law of his country, as any murderer does. The father of our hero was signer of the Declaration of Independence, who nobly ceded the Speaker’s chair to Hancock, seizing the modest candidate in his athletic arms, placing him in the chair, and then exclaiming to the members, –“we will show Mother Britain how little we care for her, by making a Massachusetts man our President, whom she has excluded from pardon by a public proclamation.” Such was the descent of General Harrison. He was born and bred in the very school of Washington, and Adams, and Madison. And through the long course of almost half a century, that he was in his country’s service, not an act, not a word, can be adduced that indicates that he preferred anything to the welfare of his country, and the permanence of her institutions. His time, his property, his domestic comfort, the temporal welfare of his family, his life, his fortune, his sacred honor, were laid on his country’s altar; and his dying breath uttered the sentiment, that next to the fear of God, had lain deepest and most cherished in his heart, as it had been the main-spring of his wonderfully active, and efficient, and protracted career– “I wish you to understand the true principles of the government– I wish them carried out– I ask nothing more.” Yes, departed sage, horseman of Israel and the chariot thereof; they shall be carried out, and the last earthly wish of thy noble heart shall be gratified! And in his statement of the principles on which he would govern the country, we have an exhibition of the apparent importance of his presence at the helm of State.

“Among the principles proper to be adopted by any Executive sincerely desirous to restore the administration to its original simplicity and purity, I deem the following to be of prominent importance:

I. To confine his service to a single term.

II. To disclaim all right of control over the public treasure, with the exception of such part of it as may be appropriated by law to carry on the public services, and that to be applied precisely as the law may direct, and drawn from the treasury agreeably to the long established principles of that department.

III. That he should never attempt to influence the elections, either by the people or the state legislatures, nor suffer the federal officers under his control to take any other part in them than by giving their own votes, when they possess the right of voting.

IV. That in the exercise of the veto power, he should limit his rejection of bills to–1. Such as are, in his opinion, unconstitutional. 2. Such as tend to encroach on the rights of the states or individuals. 3. Such as involving deep interests, may, in his opinion, require more deliberation or reference to the will of the people, to be ascertained at succeeding elections.

V. That he should never suffer the influence of his office to be used for purposes of a purely party character.

VI. That in removals from office of those who hold their appointments during the pleasure of the Executive, the cause of such removal should be stated, if requested, to the Senate, at the time the nomination of the successor is made.

VII. That he should not suffer the Executive department of the Government to become the source of legislation; but leave the whole business of making laws for the Union to the department to which the Constitution has exclusively assigned it, until they have assumed that perfected shape when and where alone the opinions of the Executive may be heard.”

These are the principles which we had fondly hoped he was going to carry out and execute. To us, they seem inseparable from the dignity of that high office, essential to the healthful action of our political system. With such an exposition made by such a man, we rejoiced to see him going up to the highest place of power and trust.

Such was General Harrison, considered in reference to the qualifications for the Presidential chair. And such is our loss. But it is the Lord who qualified him, who gave him and who has taken him. Hear then, mourning nation, the voice of the rod. It proclaims our complete, our incessant dependence on a sovereign God. Today let it be engraven on the heart of this people, and let them tell it to their children’s children; that “His dominion is an everlasting dominion, and all the people of the earth are reputed as nothing; and he doeth according to His will in the army of heaven and among the inhabitants of the earth.”

2. The dealings of Providence bring to our view our national and personal sins. This blow is but one of a series. The history of the last six years recounts the resources of the Almighty hand, when he means to visit a nation for its sins–fires, storms, disease, wrecks, perplexity, fear, murderers, rumors of war, heart-burnings, volcanic and subterranean thunderings of party strife–public distrust created by an unparalleled series of public frauds, and the breach of the public faith; these have been the inflictions superadded to ordinary inflictions, and to which the vain heart of man pays too little heed. And all these chastisements seemed to have, through our obstinacy, one defect as chastisements; they did not strike suddenly enough, nor with a sufficiently general effect, to make the nation comprehend their meaning. So this last was sent, and may it be the last? This has a two-fold efficacy–it strikes the nation like an electric shock. Probably there was not a hamlet within the broad domain of our empire, in which the cry was not heard in less than one week from its occurrence–the President is dead. And it came too just in the height and heat of the nation’s enthusiasm. Just when they would feel it most, and when the spirit of man-worship was in its most lusty stage. God lifted him up to a nation’s admiration; but at the same time held up the decree– “this day have I set my king upon my holy hill of Zion; be wise, now therefore, O ye kings, and be instructed, O ye judges of the earth; serve the Lord with fear and rejoice with trembling. Kiss the Son, lest he be angry.” The space of one short month was given, that like Nineveh we might repent and avert the impending blow. But we repented not, and the rod fell. All our sins are comprehended in this one of rejecting Christ. And all our national sins are personal sins. And the appropriate spirit and employment of this day, is the review of our personal transgressions, and the putting away of our individual atheism and unbelief, our disregard of the supremacy of Christ, and of his precious gospel. He is the true patriot, who this day carries a broken heart to his closet, and mourns over his own and our people’s sins; our worldliness and love of money, our party-spirit, our profanation of the Sabbath, our lewdness and profaneness, our neglect of the Bible and of prayer. “Kiss the Son,” as our Sovereign and your Savior, and let your entire influence be henceforth devoted to securing to him the faith, the homage and the praises of the nation. Let us repent and bring forth fruits meet for repentance. Let the ministry lay aside its sins, the country, the President, the Cabinet, the Law-makers, the Judges, the Princes, and the People all bow down this day before an offended God, and seeking the aids of his grace, promise new obedience to Him who was exalted, in order that to Him every knee might bow and every tongue confess that He is Lord, to the glory of the Father.

3. Let us learn that we must die, and how to die. The dispensation that now afflicts us, impresses on our minds two great realities; – that we must die; and, that personal piety is the only and the essential preparation for that great change. I doubt, if any event in our history has ever called forth so cordial, so extensive and impressive an expression of the genuine conviction of our country. It is remarkable, how earnestly the secular journals have echoed the question–was our noble friend prepared for the great change? And it is as remarkable how full, and how satisfactory an answer Providence is giving to that inquiry. The nation is treasuring up his doings and sayings; but none give such relief to the burdened heart, as those which show him a penitent suppliant for mercy at the foot of the cross. And he did bow there, we fully believe. For several years the claims of his Savior, and the interests of his own soul had been objects of supreme importance in his view. And his were no superficial views of piety as consisting in belonging to a particular sect, or rendering a respectful homage to Christianity in general. He regarded the gospel as designed to penetrate and renovate the heart. He said to a clergyman, “I like your views of repentance; genuine sorrow, humble confession, and a forsaking of sin, are the only things that can bring peace to the sinner, or make him a better man–“How beautifully,” said he, “is the gospel adapted to the wants of the world. God must love the penitent more than the sinless, and the forgiven penitent must love God more than those who never sinned.” And in a full accordance with our views of the nature and intent of the rite, he intended to celebrate the love of his Savior at the sacramental supper. But the facts are before the nation; he loved the Bible, the Sabbath, the ministry, the cause of evangelical religion. His message, penned in the chamber where maternal piety taught his infant lips to lisp the Lord’s prayer, presents to the nation his sense of our dependence upon the power and favor of God.

Let the nation now gather around his silent tomb. By the fresh grave let our young men learn to die. We ask the infidel there; what do you find despicable in piety? Did it make Harrison less intelligent, less energetic, less upright, less patriotic? Let the soul consumed by the feverish thirst of wealth stand there and think of one whose character was never tainted by the foul passion, one who had chosen the good part that can never be taken from him. Let the ambitious pause in his career, and see whether honors are worth so much, when they may be enjoyed so briefly, snatched away so suddenly, so early; whether it is best to sell the soul and gain the world.

Let the friend of his country there see that just what we need in our rulers, is, that conscientiousness and disinterestedness which piety creates. He had the godliness which is profitable for the life that is, and for that which to come.

“It is appointed unto men once to die; and after that, the judgment.” Fellow citizens, are you prepared for judgment? Could his voice be heard amidst us again, think you it would teach you to disregard the mercy of God and to despise his anger? Oh no; my countrymen, no. Pause, pause, he would say; pause ere you rush into the holy presence where my soul is now standing in holy fear and rapture. Young men, cease to struggle for party and for power. Political men, cease your schemes of vain ambition. Where are my laurels now? Behold them already withered in the tomb. Where is the power and glory of my envied elevation? Evaporated by one breath of disease. Where is my soul? Here, where no political party no military renown, no classic lore, no national gratitude, no personal worth, has raised me; but that grace of Christ to which I fled, as a perishing sinner. Living, I would have labored for your temporal good, and I would have labored for your temporal good, and I would have shewn you an imperfect though honest example of obedience to Christ. But that was not permitted me. To my emancipated spirit, it is only permitted to utter one word more of counsel. It is this–“Be ye also ready.”

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution. Peabody graduated from Harvard in 1826 when only fifteen years of age. He then entered Harvard Divinity School for three years, also serving as a mathematical tutor. In 1833, he was ordained as minister of South Parish Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he remained for 27 years until 1860. After leaving his church, he returned to Harvard, where he served the next 21 years in various positions, including Professor of Christian Morals, preacher to the university, and twice as president, once in 1862, and then from 1868-1869. Peabody was a noted writer, having many of his sermons published as well as a Sunday School hymnbook he composed. He also penned some sixty articles from 1837-1859 in The Whig Review magazine; worked for the North American Review from 1852-1861; and likewise wrote for “The Christian Examiner,” “The New England Magazine,” “The American Monthly,” and other religious periodicals. In 1863, he was awarded a doctorate from the University of Rochester, and on July 3, 1875, he delivered the centennial address at Cambridge, Massachusetts, upon the 100th Anniversary of George Washington’s taking command of the Continental Army.

Peabody graduated from Harvard in 1826 when only fifteen years of age. He then entered Harvard Divinity School for three years, also serving as a mathematical tutor. In 1833, he was ordained as minister of South Parish Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he remained for 27 years until 1860. After leaving his church, he returned to Harvard, where he served the next 21 years in various positions, including Professor of Christian Morals, preacher to the university, and twice as president, once in 1862, and then from 1868-1869. Peabody was a noted writer, having many of his sermons published as well as a Sunday School hymnbook he composed. He also penned some sixty articles from 1837-1859 in The Whig Review magazine; worked for the North American Review from 1852-1861; and likewise wrote for “The Christian Examiner,” “The New England Magazine,” “The American Monthly,” and other religious periodicals. In 1863, he was awarded a doctorate from the University of Rochester, and on July 3, 1875, he delivered the centennial address at Cambridge, Massachusetts, upon the 100th Anniversary of George Washington’s taking command of the Continental Army.

Francis William Pitt Greenwood (1797-1843) Biography:

Francis William Pitt Greenwood (1797-1843) Biography:

Born to farming parents, Sprague attended Colchester Academy and then attended Yale, where he graduated in 1815. He was invited to be the tutor for the children of Virginian Major Lawrence Lewis, nephew of George Washington. (Lewis’ wife was the granddaughter of Martha Washington.) He accepted, and traveled from Connecticut to Virginia. The Lewis’ home, Woodlawn, was part of the original Mount Vernon (George Washington’s home), and over the year Sprague stayed with the family, he received permission from Bushrod Washington (George Washington’s nephew who served on the US Supreme Court) to go through many of George Washington’s letters and papers. Sprague was allowed to take as many of those letters as he wanted, so long as he left copies of all letters he took, which was about 1,500. From these letters, Sprague was able to compile the very first complete set of autographs of all of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. In 1816, Sprague returned to school at the Theological Seminary at Princeton, where he studied for three years. In 1819, he became an associate pastor at First Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts, and remained there a decade before becoming pastor of Second Presbyterian in Albany, New York, where he remained until 1869. Sprague was a prolific writer, and penned sixteen major works, including biographies of important American Christian leaders as well as religious works such as Lectures on Revivals of Religion (1832), Contrast Between True and False Religion (1837), and Words to a Young Man’s Conscience (1848). He also wrote over 100 religious pamphlets and smaller works. Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society, much of his writing and preaching was of a historical and biographical nature. In fact, one of his greatest accomplishments was his nine-volume Annals of the American Pulpit, which was particularly rich with biographies of those pastors who played important roles in the American War for Independence. By the time of Sprague’s death in 1876, he had collected over 100,000 historical autographs, including three complete sets of signatures of all the signers of the Declaration; one set of all the members of the Convention that framed the US Constitution; a complete set of the autographs of the first six Presidents of the United States and the officers of their administrations (including signatures of the Presidents, Vice Presidents, Cabinet members, US Supreme Court Justices, and all foreign ministers in those administrations); and the signatures of all military officers involved in the American War for Independence, regardless of the nation from which they came or the side of the war on which they fought. He also collected signatures of leaders of the Reformation as well as those of great skeptics and opponents of religious faith. His collection was considered the largest private collection in the world at the time of his death.

Born to farming parents, Sprague attended Colchester Academy and then attended Yale, where he graduated in 1815. He was invited to be the tutor for the children of Virginian Major Lawrence Lewis, nephew of George Washington. (Lewis’ wife was the granddaughter of Martha Washington.) He accepted, and traveled from Connecticut to Virginia. The Lewis’ home, Woodlawn, was part of the original Mount Vernon (George Washington’s home), and over the year Sprague stayed with the family, he received permission from Bushrod Washington (George Washington’s nephew who served on the US Supreme Court) to go through many of George Washington’s letters and papers. Sprague was allowed to take as many of those letters as he wanted, so long as he left copies of all letters he took, which was about 1,500. From these letters, Sprague was able to compile the very first complete set of autographs of all of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. In 1816, Sprague returned to school at the Theological Seminary at Princeton, where he studied for three years. In 1819, he became an associate pastor at First Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts, and remained there a decade before becoming pastor of Second Presbyterian in Albany, New York, where he remained until 1869. Sprague was a prolific writer, and penned sixteen major works, including biographies of important American Christian leaders as well as religious works such as Lectures on Revivals of Religion (1832), Contrast Between True and False Religion (1837), and Words to a Young Man’s Conscience (1848). He also wrote over 100 religious pamphlets and smaller works. Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society, much of his writing and preaching was of a historical and biographical nature. In fact, one of his greatest accomplishments was his nine-volume Annals of the American Pulpit, which was particularly rich with biographies of those pastors who played important roles in the American War for Independence. By the time of Sprague’s death in 1876, he had collected over 100,000 historical autographs, including three complete sets of signatures of all the signers of the Declaration; one set of all the members of the Convention that framed the US Constitution; a complete set of the autographs of the first six Presidents of the United States and the officers of their administrations (including signatures of the Presidents, Vice Presidents, Cabinet members, US Supreme Court Justices, and all foreign ministers in those administrations); and the signatures of all military officers involved in the American War for Independence, regardless of the nation from which they came or the side of the war on which they fought. He also collected signatures of leaders of the Reformation as well as those of great skeptics and opponents of religious faith. His collection was considered the largest private collection in the world at the time of his death.

Palfrey’s grandfather, William Palfrey, had been active during the American War for Independence, working for John Hancock, being aide-de-camp for George Washington, and then serving as the Continental Congress’ diplomat to France. The grandson was born during George Washington’s presidency and graduated from Harvard in 1815, during James Madison’s presidency. He studied theology, and three years later in 1818 became pastor of Boston’s Brattle Street Church. In 1831, he left the church to be Professor of Sacred Literature at Harvard, eventually becoming dean of the theological faculty and one of three preachers at the university chapel. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, he became involved in government, serving in the US House of Representatives from 1842-1843 and 1847-1849, and as Secretary of State in the years between. He served as Boston’s postmaster from 1861-1867, then went to Europe in 1867, serving as US representative to Anti-Slavery Congress in Paris. He penned numerous works, including the History of New England to 1875, The Relationship between Judaism and Christianity, Academical Lectures on the Jewish Scriptures and Antiquities, and Discourse . . . [on] the Second Centennial Anniversary of the Settlement of Cape Cod. He also served as editor of the Commonwealth newspaper and the North American Review.

Palfrey’s grandfather, William Palfrey, had been active during the American War for Independence, working for John Hancock, being aide-de-camp for George Washington, and then serving as the Continental Congress’ diplomat to France. The grandson was born during George Washington’s presidency and graduated from Harvard in 1815, during James Madison’s presidency. He studied theology, and three years later in 1818 became pastor of Boston’s Brattle Street Church. In 1831, he left the church to be Professor of Sacred Literature at Harvard, eventually becoming dean of the theological faculty and one of three preachers at the university chapel. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, he became involved in government, serving in the US House of Representatives from 1842-1843 and 1847-1849, and as Secretary of State in the years between. He served as Boston’s postmaster from 1861-1867, then went to Europe in 1867, serving as US representative to Anti-Slavery Congress in Paris. He penned numerous works, including the History of New England to 1875, The Relationship between Judaism and Christianity, Academical Lectures on the Jewish Scriptures and Antiquities, and Discourse . . . [on] the Second Centennial Anniversary of the Settlement of Cape Cod. He also served as editor of the Commonwealth newspaper and the North American Review. Born in Connecticut to a well-known family, he graduated from Yale in 1804. He worked as an educator for several years, then began studying law. In 1812, he passed the bar and went to work as a lawyer in Newbury, Massachusetts. But being dissatisfied as an attorney he became a merchant in Boston, then Baltimore, and next entered the study of theology. He graduated from Cambridge Divinity School and was ordained in 1819. He pastored a Boston church until 1845, then a church in Troy, New York, until 1849, and then another church in Massachusetts, where he pastored until 1856. While a pastor, Pierpont penned two of the more popular classroom school readers of that day. He was an abolitionist, a member of the temperance movement, a Liberty Party candidate for governor in the 1840s, and then a Free-Soil Party candidate for governor in 1850. He served as a Massachusetts field chaplain during the Civil War, but the physical demand was too great for his aging body, so he took an appointment in the Treasury Department in Washington, where he worked until his death in 1866. He was an accomplished poet and penned many published poems as well as sermons.

Born in Connecticut to a well-known family, he graduated from Yale in 1804. He worked as an educator for several years, then began studying law. In 1812, he passed the bar and went to work as a lawyer in Newbury, Massachusetts. But being dissatisfied as an attorney he became a merchant in Boston, then Baltimore, and next entered the study of theology. He graduated from Cambridge Divinity School and was ordained in 1819. He pastored a Boston church until 1845, then a church in Troy, New York, until 1849, and then another church in Massachusetts, where he pastored until 1856. While a pastor, Pierpont penned two of the more popular classroom school readers of that day. He was an abolitionist, a member of the temperance movement, a Liberty Party candidate for governor in the 1840s, and then a Free-Soil Party candidate for governor in 1850. He served as a Massachusetts field chaplain during the Civil War, but the physical demand was too great for his aging body, so he took an appointment in the Treasury Department in Washington, where he worked until his death in 1866. He was an accomplished poet and penned many published poems as well as sermons.