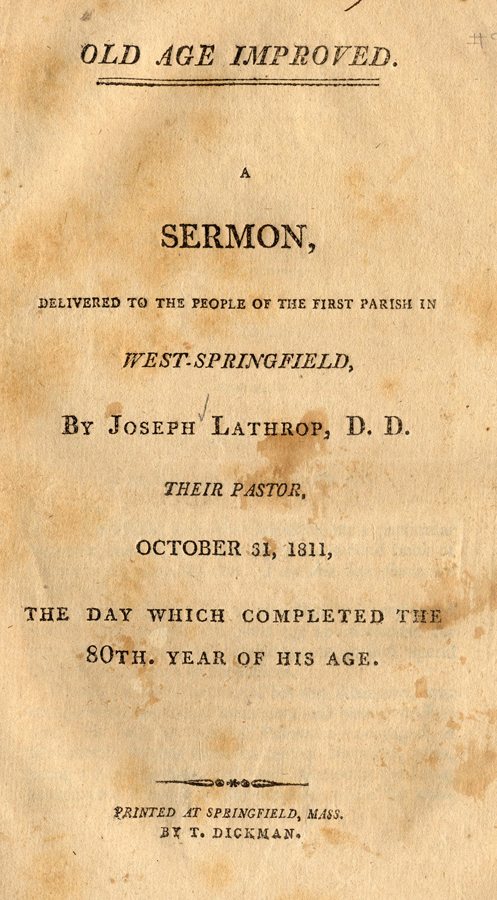

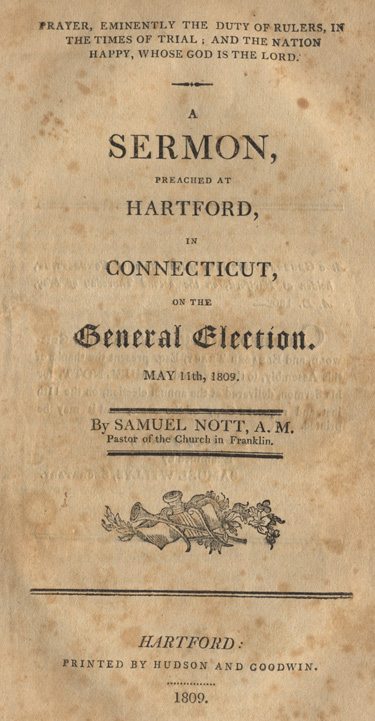

Samuel Nott (1754-1852) graduated from Yale in 1780. He studied divinity under Jonathan Edwards and was pastor of the Franklin, CT Congregational Church (1781-1852). Nott preached this election sermon in Hartford on May 11, 1809.

THE TIMES OF TRIAL; AND THE NATION

HAPPY, WHOSE GOD IS THE LORD.

A

SERMON,

PREACHED AT

HARTFORD,

IN

CONNECTICUT,

ON THE

GENERAL ELECTION.

May 11th, 1809.

By SAMUEL NOTT, A. M.

Pastor of the Church in Franklin.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, on the second Thursday of May, A. D. 1809.

ORDERED, that the Honorable Matthew Griswold, and Eleazer Tracy, Esq. present the thanks of this Assembly, to the Reverend SAMUEL NOTT, for his Sermon, delivered at the annual election, on the 11th inst. And request a Copy of the same that it may be printed.

A true copy of record,

Examined by

SAMUEL WYLLYS, Secretary.

PSALM CXLIV. 11-15.

Rid me, and deliver me from the hand of strange children, whose mouth speaketh vanity, and their right hand is a right hand of falsehood: That our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth; that our daughters may be as corner stones, polished after the similitude of a palace: That our garners may be full, affording all manner of store; that our sheep may bring forth thousands and ten thousands in our streets: That our oxen may be strong to labour; that there be no breaking in, nor going out; that there be no complaining in our streets. Happy is that people, that is in such a case: yea, happy is that people, whose God is the Lord.

MAN was made for society: that, which was first enjoyed, was of the domestic kind.

As man multiplied, iniquity abounded. “Every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.—The earth also was corrupted before God: and the earth was filled with violence.” 1

Under these circumstances, the public good rendered it necessary, that government should have some additional form. 2

All nations, excepting the Hebrew, whose political system was expressly appointed by God, have been left, to take such a form of government, as suited them best. Whatever form they have adopted, they have, necessarily, been obliged to relinquish some of their natural rights, in order to have the rest secured.

The monarchical, aristocratical, and democratical are the principal forms that have been adopted. All others are but a mixture of these. Each has its advantages and disadvantages, its advocates and opposers.

The design of all righteous governments, is the defense and happiness of the community. He is the minister of God to thee for good. Whatever form be adopted, it will be imperfect, and fall short, in a measure, of the end proposed; nevertheless, as the members of the natural body are subject to their head, so ought those to be, in the body politic. A very imperfect government is unspeakably better than no government.—It is not always owing to any special defect, either in the constitution, or the administration, that government falls short of its design. The fault is often owing to the people themselves,

As in the natural body, notwithstanding the consummate wisdom, in its organization, there are many and grievous maladies, so it may be expected in the political body; there will often be innumerable and incalculable evils. It is evident from history, that this has ever been the case, and it may be expected that it ever will be, so long as human nature shall remain in its fallen, debased state.

By the apostacy, man lost his glory, the moral image of God. The whole human race by nature are selfish creatures, inclined to evil, and that continually. New and unexpected trials therefore, will be likely, frequently to spring up, in all governments, however wise the rulers, and righteous their administration. The patience and power of those in authority will, of consequence, often be put to the test. David king in Israel, “the man after God’s own heart,” was not exempted.

What is the proper course to be pursued, under these circumstances?—And the way for a people, ever to be happy? Are very interesting enquiries.

As the words of our text point out both, it is thought that they are therefore, particularly, worthy of attention, upon this anniversary: And though I believe with a celebrated writer that, both liberty and property are precarious, unless the possessors have sense and spirit enough to defend them; 3 as a minister of Christ, I shall attempt.

I. To show, that in the times of peculiar trial, it is eminently the duty of rulers to be men of prayer.

II. To illustrate the closing declaration, in our text.

That in the times of peculiar trial, it is eminently the duty of rulers, to be men of prayer, is evident from the consideration, that their labours and temptations are usually then greatly increased—their safety, honour and happiness, the safety, honor and happiness of their subjects and offspring likewise, greatly exposed.—Notwithstanding their elevated stations, however great their natural, or acquired abilities, they are dependent, weak, short sighted, dying men, and always need support and aid from on high, but especially in the times of peculiar trial.

The following directions must apply to them, as well as to other men: “Is any among you afflicted? Let him pray. If any lack wisdom let him ask it of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not. 4 Call upon me in the day of trouble: 5

The example of pious rulers, left on divine record, puts the matter beyond all reasonable doubt.

The example of David in our text claims our first attention, who soon after he came to the throne had great trials, from the Philistines and other foreign enemies. In consequence of which, probably, he composed the psalm of which our text is a part.

The several petitions which, probably, he composed the psalm of which our text is a part.

The several petitions in our text, as they evince, in a peculiar manner, some of the feelings, which all rulers ought to possess, deserve to be distinctly considered: Rid me and deliver me from the hand of strange children, whose mouth speaketh vanity, and their right hand is a right hand of falsehood.

David, when he made this prayer, felt himself encompassed by dangers, and realized his own weakness, and the ability of the Lord Jehovah, to deliver him out of the hands of his enemies, whether Israelites or heathen; whose mouth spake vanity; and their right hand was a right hand of falsehood. His enemies, no doubt, possessed a lying spirit to a great degree.

Much in every age is to be feared from the tongue, which, though a little member, is naturally full of deadly poison. 6 Persons who have no regard to truth, will readily even perjure themselves, to injure those whom they hate, whenever they imagine, that they can do it with impunity.

In this dangerous situation, David looked directly to the Lord, who perfectly understood the malice and devices of his enemies, and was able utterly to disappoint them. He was not merely concerned for his personal honour and safety, but, as becomes all rulers, for the good of his subjects. He felt a deep concern for those in the morning of life, and fervently prayed in these words: That our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth. He not only wished that the young men in his kingdom might be healthy and vigorous, fitted for the most active services, but possessed of all the manly and social virtues. He well knew, that according to the common course of divine providence, all persons then on the stage of life, even the pillars of the church and society, were soon to be carried to the land of silence, and to rest with their fathers. The anxious feelings of his heart, for the rising generation, led him to add the following very expressive petition: That our daughters may be as corner stones, polished after the similitude of a palace. The corner stones of a palace are stones of the most durable kind, chosen with great care, hewed and polished by the most skillful artists, and so placed, as to be essential to the support of the building.

The situation of women in civil society, though they have no share in the government in our country, is in many points of view vastly important, but especially, as the education and government of children, in the early part of life, rest very much upon them. They give a cast to their minds and manners; and of consequence to the minds and manners of the community. Not only the Poet hath said:

“Just as the twig is bent, the tree’s inclin’d;”

But the wise man, under the inspiration of the holy Ghost: “Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it.”

Early education and government, not only have a great influence on social order, but religion. Timothy was partaker of the same faith, which was first in his grandmother Lois and his mother Eunice. 7

As, it is appointed unto men, once to die, and the wheels of time never stop, David well knew, that daughters would soon take the place of their mothers, as the mistresses of families, and have the care of the nursery of the church and nation. He therefore ardently wished, that they might be truly amiable, and so trained to the habits of industry and morality, as to be in the best manner furnished for their important betrustment.

The royal suppliant wished for the increase of the wealth of his subjects, as well as for the improvement of their minds and manners. His own words are, That our garners may be full, affording all manner of stores. He desired not only, that their garners might be full, but their flocks fruitful, and added to the foregoing, the following petition: That our sheep may bring forth thousands, and ten thousands in our streets: That our oxen may be strong to labour. In his youth he had been accustomed to a pastoral life, and knew well the value of flocks and herds. He was sensible that their increase and perfection, would add greatly to the wealth, strength and respectability of the nation. As became a dependent creature therefore, he looked to God for them, by whose aid alone they could be effected.

The next petition is: That there be no breaking in nor going out. This may be considered, either as a prayer, that the Israelites might not be disturbed by other nations, nor disturb any themselves, by making war upon them, but “sit every man under his own vine, and under his own fig tree, and have none to make afraid;” 8 or as a prayer, that adjoining fields should be so enclosed, that beasts should not break from one to another, destroy the crops and impoverish their owners:–viewed in either light, or in both, it shows the benevolence of the King of Israel, and his desire for the happiness of his people.

He closes his prayer, in these words: That there be no complaining in our streets. King David was determined, so to wear the sword of justice, as to give no occasion for complaining. He loved peace, and ardently wished for it, throughout his kingdom. Nevertheless, he well knew the natural wickedness and impatience of men, that they were restless as the ocean, and wont to complain. And that designing men, were wont to do it in the streets, the places of public resort; no doubt to discredit the government, in the view of the populace, and to raise themselves into office. This vile and dishonourable custom, he wished might not disgrace his kingdom. But that his subjects, if they were dissatisfied with government, might pursue rational and constitutional methods, to have their grievances redressed, whether real, or imaginary.

Having taken a brief view of the several petitions in our text, it is in point to observe, as a further evidence of our general object, that David, at a later period, when he was obliged o flee before his son Absalom, 9 was an earnest suppliant, at the throne of divine grace, if, as is supposed, he composed the following Psalm, upon that memorable occasion: “Lord how are they increased that trouble me? Many are they that rise up against me. Many there be who say of my soul, there is no help for him in God. But thou, O Lord, art a shield for me: my glory, and the lifter up of mine head. I cried unto the Lord with my voice, and he heard me out of his holy hill. I laid me down and slept, I awaked, for the Lord sustained me. I will not be afraid of ten thousands of people, that have set themselves against me round about. Arise, O Lord, save me, O my God; for thou hast smitten all mine enemies upon the cheek bone: thou hast broken the teeth of the ungodly. Salvation unto the Lord: thy blessing is upon thy people.” 01

Solomon, soon after he came to the throne, was greatly tried in the conduct of Adonijah, Abiathar and Joab. 11—When God said; “Ask what I shall give thee,” he said, “Thou hast showed unto thy servant David my father great kindness, that thou hast given him a son to sit on his throne, as it is this day.”

“And now, O Lord my God, thou hast made thy servant king instead of David my father: and I am but a little child: I know not how to go out, or come in. And thy servant is in the midst of thy people, which thou hast chosen, a great people that cannot be numbered nor counted for multitude. Give therefore thy servant an understanding heart, to judge thy people, that I may discern between good and bad: for who is able to judge so great a people.” 12

Nehemiah says, “I sat down and wept and mourned certain days, and fasted, and prayed before the God of heaven, the great and terrible God, that keepeth covenant and mercy for them that love him, and observe his commandments; let thine ear now be attentive and thine eyes open, that thou mayest hear the prayer of thy servant, which I pray before thee now, day and night, for the children of Israel thy servants, and confess the sins of the children of Israel, which we have sinned.—O Lord, I beseech thee, let now thine ear be attentive to the prayer of thy servant.” 13

I shall now, as proposed, attempt to illustrate the closing declaration, in our text: Happy is that people, that is in such a case, yea happy is that people whose God is the Lord.

That people is happy, in a degree, who have neither foreign nor domestic enemies, who are blessed in their basket and store, and where he rising generation are formed, for ornament and usefulness.

The royal Psalmist had a view to a people of this description, when he says, happy is that people, that is in such a case. But he exclaims in the succeeding clause, yea happy is that people, whose God is the Lord: As though he had said, that is the happy people, who are the subjects of real religion, the worshippers of the true God, and who have him, for a covenant God and father.

It may therefore be useful, briefly to state

1. In what true religion consists.

2. In what sense, that people is happy, who are the subjects of it.

True religion consists in right views. Affections and conduct.

In right views, of the nature and tendency of things.

In right views of God—Of his natural and moral perfections—his omnipotence, omnipresence, omniscience, holiness, justice, goodness and truth—right views of his government, as general and particular, respecting, not only, the rolling of the spheres, the rising and falling of empires, but of every mote that flies in the air, the numbering of the hairs, upon every head, and the falling of a sparrow, though two of them are sold for a farthing.

In right views of ourselves—of our absolute dependence upon God—that in him we live, move and have our being—that, “he appoints the bounds of our habitation,” 14 is the author of all our talents, and points out our various occupations in life. But especially, in right views of our moral character; that by nature, “we are alienated from the life of God” 15 and are under the curse of his law.” 16

In right views of our neighbours—like ourselves, absolutely dependent upon God, possessed of similar capacities for happiness and usefulness—similar moral characters, having various relations, natural, civil, social and religious, under the same law, bound to the same world, and ultimately accountable to the same judge.

In right views of this world: Of its real worth: “For every creature of God is good, and nothing to be refused, if it be received with thanksgiving: 17 –Likewise of its unsatisfying nature, great mutability and certain dissolution; that though “the Lord in the beginning hath laid the foundations of the earth, and the heavens are the works of his hands; they shall perish—they shall wax old as a garment: and as a vesture shall he fold them up, and they shall be changed.” 18

In right views of the future world: As eternal; our final home; the place of rewards and punishments, where we shall all reap the proper fruit of our conduct on earth, whether it be virtuous or vicious,

In right affections, towards God and creatures, rational and irrational, rulers and subjects, saints and sinners, this world and the world to come.—In loving God, “with all the heart, with all the soul, and with all the mind, and our neighbours as ourselves.” 19

In deep contrition for sin, on account of its infinite malignity, as tending to the destruction of the moral kingdom.

In faith in the great Redeemer, that faith which unites the soul to him, brings it into covenant with God, which transforms into the divine likeness, and influences every possessor to pant after God; “as the hart panteth after the water brook;” 10 to feeling some measure, as the Psalmist felt, when he said, “whom have I in heaven, but thee? And there is none upon earth that I desire beside thee? 21

In right conduct; in faithfully discharging our duty in every station and relation, to our creator, and fellow creatures. There are appropriate duties for the poor and the rich, for ministers and people, for rulers and their subjects. Religion respects the discharge of them all. John, who preached, “bring forth fruits worthy of repentance,” when “the people,” who heard him, “asked him, what shall we do? answered and said unto them, he that hath two coats, let him impart to him that hath none: and he that hath meat let him do likewise. Then came also publicans to be baptized and said unto him, Master what shall we do? And he said unto them, exact no more than that which is appointed unto you. And the soldiers likewise demanded of him, saying, and what shall we do? And he said unto them, do violence to no man, neither accuse any falsely, and be content with your wages. 22

Rulers, however exalted their stations, have duties to perform. They are God’s servants. He has raised them to their places of honour and usefulness: “By him kings reign and princes decree justice. By him do princes rule and nobles, even all the judges of the earth.” 23 They are raised to the places of honour, not for their own advantage, but that they may be useful to society. “He is not a terror to good works, but to the evil—he is a minister of God to thee for good—He beareth not the sword in vain; for he is the minister of God—a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil.” 24

Rulers ought to do good, not only to civil society, but to the church of Christ. The latter, indeed, ought to be the governing object, in all their conduct.

The church, the kingdom of the Redeemer, is the kingdom, to which all others are to be subjected. This is the kingdom which shall never be destroyed—the kingdom that shall not be left to other people, but shall break in pieces, and consume all other kingdoms, and stand forever. 25 Rulers are under the highest obligation to do all in their power, for its perfection and beauty, and the time is fast hastening, when the following prediction, will have its full accomplishment: “And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers.” 26

There are duties, not only for rulers, but for their subjects. They must lead quiet and peaceable lives in all honesty and godliness. As it is the duty of rulers to rule, so it is of subjects to obey all legitimate authority: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers:–Whoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God, and they that resist, shall receive to themselves damnation—But if thou dost that which is evil be afraid.—Wherefore you must needs be in subjection not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake.” 27 It is not enough to obey through fear of fines and imprisonment. It ought to be done, from a sense of duty.

Subjects ought not only to obey, but as they have the protection of their property, reputation and lives, to contribute according to their ability, to defray the expenses of government: “For, for this cause pay ye tribute: for they are God’s ministers attending continually upon this very thing! 28

They ought indeed, to observe universal justice. The divine command is, “Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due, custom to whom custom, fear to whom fear, honour to whom honour. Owe no man anything, but to love one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law. 29 “Render therefore unto Cesar, the things which are Cesar’s, and unto God the things which are God’s.” 30

It remains to show in what sense that people is happy, who are the subjects of true religion.

They are not happy, in that sense which implies an absolute freedom from sin: “For there is not a just man upon earth, that doth good and sinneth not.” 31

Neither are they happy, in that sense which implies a deliverance from all natural evil: “But if ye be without chastisement, whereof all are partakers, then are ye bastards and not sons.” 32 Nevertheless, they are happy.

As those exercises of mind, peculiar to religion are in their nature pleasurable.

They are not pleasurable, to persons of a corrupt, unholy taste, “who drink in iniquity like water,” 33 and would, were it in their power, readily sacrifice the universe, to gratify their own selfish feelings. But to those who have a correct moral taste, “wisdom’s ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace. 34 The statutes of the Lord are more to be desired than gold, yea than much fine gold, sweeter also than honey or the honey comb.” 35

The justice, mercy and self denial of the gospel are all repugnant to the selfish feelings of the human heart, but are perfectly consonant to those of disinterested love.

They are happy, as they are willing to stand in their lot, which they view as the result of infinite wisdom, and ardently wish to improve all their talents for the public good. They mean to be at their post, however great the danger, and faithfully to discharge the duties to which they may be called. They have no anxious feelings for worldly honours.

No one says, in the language of Absalom, “Oh that I were made judge in the land, that every man who hath any suit or cause might bring it unto me, and I would do him justice;” 36 but each feels a degree of emulation, to excel in doing well, to advance, as far as is possible, the beauty, strength and perfection of society, whether called to act in a public or private capacity.

They are likewise happy, as they have a fixed confidence in God, both in prosperity and adversity; and feel assured, by reason of his transcendent wisdom, almighty power and infinite goodness, that to whatever height infidelity may arise, however great the shaking may be among the nations, or whoever may rise or fall in a political view, that all things, eventually, will come to the wisest issue. They give full credit to the testimony of Asaph: “Surely the wrath of man shall praise thee: the remainder of wrath shalt thou restrain.” 37 It is the joy of their hearts, that, “the Lord reigneth;” 38 that he is able to turn the counsels of an Ahithophel to foolishness, 39 to cause one to chase a thousand and two to put ten thousand to flight, 40 that, “his counsel shall stand, and that he shall do all his pleasure,” 41 that, “of him and through him and to him are all things,” 42 and that all false religions shall eventually fall before the true, as Dagon fell upon his face, when the Philistines brought the ark of the Lord into the house of Dagon.” 43

It may be added, that they are happy, as they all observe the same rule of conduct, look at the same great object, and that however different their callings, and variegated their circumstances, they are ultimately to share in the same good. Their rule of conduct is the moral law. Their governing object, the pole star in their journey of life, in the field, in the family, and in the cabinet, whether they eat, or drink, or whatever they do, is the glory of God. The good in which they hope eventually to share, is the eternal enjoyment of God, and the felicity of that kingdom, where nothing shall enter that defileth: 44 where the whole prospect shall be without a cloud: where all the affections of the subjects shall be perfectly holy, and their happiness without alloy, and without end.

As it is, eminently, the duty of rulers, in the times of peculiar trial, to be men of prayer, with great propriety, upon this anniversary, it may be remarked, that it is of vast importance, that they should be religious men. No others will ever ask counsel of God, in a becoming manner, in the times of peculiar trial, nor indeed at any time.

No others, therefore, ever ought to be promoted by a free people. In no others can confidence be safely placed, any farther than the public interest can be rendered subservient to their own.

Honour, which is often made a substitute for religion, though the word has a pleasant sound, affords no certain security. If anything is meant by it, distinct from natural conscience, it must respect mere personal dignity, and as really originate from a selfish heart, as the spirit of revenge. There is no possible medium, between selfishness and benevolence. That which is really selfish, by whatever name it be called, can never afford permanent security. The history of ages shows that honour hitherto has failed, in the times of temptation, to afford security either to property, chastity, reputation, or life.—Persons actuated by no higher motive than personal dignity, may for a season do well.—It is wise for a people, nevertheless, in choosing their rulers, always to observe Jethro’s direction to Moses: “Provide out of all the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness.” 45

Though all good men are not fit for rulers, it is fully evident from the last words of David, the man after God’s own heart, that it is men of the above description, who ought to be promoted: “The God of Israel said, the rock of Israel spake to me. He that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God. And he shall be as the tender grass springing out of the earth, by clear shining after rain.” 46 In his charge to Solomon, his son and successor, he said, “I go the way of all the earth: be thou strong therefore, and show thyself a man. And keep the charge of the Lord thy God, and walk in his ways, to keep his judgments and his testimonies, as it is written in the law of Moses, that thou mayest prosper in all that thou doest and whethersoever thou turnest thyself.” 47

Rulers, who really are religious men, believe in the existence and government of a holy God. They have fixed moral notions, and expect to give an account of their conduct.—Whether they act in a legislative or executive capacity, they are much more concerned to promote the good of the community, than to receive any private emolument. They dread doing anything, which will not bear the most critical, public examination, and meet the approbation of God. They are therefore, the men to be trusted.

The illustrious Washington, when consulted about accepting the Presidency of the United States, said: “Nor will you conceive me to be too solicitous for reputation. Thou I prize, as I ought, the good opinion of my fellow-citizens, yet if I know myself, I would not seek or retain popularity at the expense of one social duty, or moral virtue. While doing what my conscience informed me was right, as it respected my God, my country and myself, I could despise all the party clamour and unjust censure, which must be expected from some, whose personal enmity might be occasioned by their hostility to the government.—I am conscious that I fear alone to give any real occasion for obloquy, and that I do not dread to meet with unmerited reproach.” 48

Religion really forms men, whether rulers or subjects, on the best model, both for usefulness and happiness, as it inclines them to sacrifice private interest, for the public good. It binds them to God, and to one another, by an indissoluble bond. It is useful in all governments, but especially in a popular one. The illustrious patriot and statesman before mentioned, said: “Reason and experience, both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.—It is substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring to popular governments.”

True virtue, or real religion, not only overcomes the selfishness of the human heart, but tends to restrain men from intemperance, lasciviousness, Sabbath breaking, profaneness, dueling, suicide, and all kinds of immoralities, and to animate them to whatever is wise, benevolent and noble. It enlarges the mind, warms the heart, and gives an energy to action, and a dignity to character, that nothing else can give.

Though religion tends to make those persons who possess it, the best of citizens, and to render them the most worthy of promotion, it is notoriously true of some, who profess it, that they are neither honest, nor orderly. The Christian name is only a cloak to them. They fight under false colours; are mere time servers, and care for nothing but the loaves and the fishes. Such persons, notwithstanding their profession, have no title to the confidence of the people.

To the want of proper care, with respect to the character of persons, in appointing the officers of government, may be traced some of the greatest political evils.

Taking into view our peculiar privileges, civil and religious, and our imminent danger from public enemies, and from those more unnatural, in the bosom of our own country, who it is to be feared are secretly endeavouring to subvert its liberties, it is suitable likewise to remark, though with becoming deference, that there are many things in the providence of God, calculated to call the attention of His Excellency, and all the members of the Honourable Legislature, to the important duty of prayer.—Important in various respects, especially, as it tends to fit them for whatever may take place, and to lead them to discern, and to discharge their duty, with honour to themselves, the best good of their constituents and the glory of God. He who rightly discharges this duty, whatever be his station, may hope to be enabled, so to discharge every other, that should his enemies attempt to find occasion against him, they would be necessitated to say, in the language of the presidents and princes of the Persian court, concerning Daniel: “We shall not find any occasion against him, except we find it against him concerning the law of his God.” 49 What a high, though undersigned commendation of Daniel! How worthy his example of imitation, by the members of this Legislature; who are called to represent, and legislate for a people possessed, probably, of the most rational notions of civil and religious liberty, of any on the globe! The rust is vastly great. Fidelity is of the utmost importance. The signs of the times, notwithstanding the friendly accommodation, with one of the European powers, are still alarming. The guidance of heaven, is of the highest importance. May it be fully realized, and sincerely and importunately sought, in the ensuing session! It is better to trust in the Lord than to put confidence in man. It is better to trust in the Lord, than to put confidence in princes.” 50

The mechanical, mercantile and agricultural interest, indeed all the different interests of the state, will as usual be represented, and claim the attention of this assembly. Private interest, however, ought not to be the governing object, with any member, but the public good. If that should be carefully sought, so far as the chief magistrate, the council, and representatives, express the public mind, the state will be like a threefold cord, not easily broken. No scheme against our liberties, however deeply laid, will be likely to prosper. But if private interest should prevail, the state will be like a rope of sand, without strength. Its dissolution will be inevitable. A kingdom divided against itself cannot stand.

Among the various interests of the State, as learning is essential to the existence of a free people, it is much to be desired, and confidently to be expected, that the college, academies, and all the minor schools, as they have in times past received the liberal patronage of the Assembly, so they will, in the time to come, be favoured with their nurturing hand, and the State, long and deservedly, be considered as the “Athens of America.”

Though learning is essential to the existence of a free people, without virtue, it is a poor safeguard. It is an entirely mistaken notion, which many persons have imbibed, that if men only have information, they will do right. It is true religion alone, that can insure this happy effect. Of consequence, it is of the first importance to possess it. “Righteousness exalteth a nation: but sin is a reproach to any people.” 51 Rulers themselves ought to possess it. The inspired Psalmist therefore saith: Be wise now therefore, O ye Kings; and be instructed ye judges of the earth, serve the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling. Kiss the son, lest he be angry and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little; blessed are all they that put their trust in him. 52

Rulers ought not only to possess religion themselves, but carefully, by their lives and conversation, to recommend it to others. Though they are to bind no man’s conscience, but to leave each one, in matters of religion, to act for himself, they ought to distinguish, between true religion and false, between the various pretended revelations—between the Zehdavista of Zoroaster, 53 the oracles of the Sibyls, 54 the Shaster of the Banians, 55 the Alcoran of Mahomet, and the Scriptures of the old and new testament—between modern philosophy and gospel benevolence, between the corruptions of Christianity, and the doctrines which stain the pride of all glory, taught by Moses and the Prophets, Christ and the Apostles!

It is of vast importance, that rulers should understand and promote true religion, as it tends in a peculiar manner, to render persons useful and happy, by making them honest, peaceable, industrious and ready to every good work: and as it tends to entail blessings, upon their unborn posterity.

All the members of the Legislature, in the ensuing session, ought to act under its benign influence, and to do all in their power, to advance its true interest.—When the session shall close, and they return to their families, and mingle again with their constituents, it will be their duty to carry it with them. This will not only secure them the divine approbation, but be the most likely way, to cement the various parts of society, and to influence all classes of people, to be virtuous, orderly and happy. When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice, but when the wicked beareth rule the people mourn. 56 May the session be free from a party spirit, 57–all the deliberations of the body be candid—their determinations the result of real wisdom, patriotism and religion, and the blessing of the God of our pious ancestors, rest upon all the members.

As the subjects of true religion are happy, it may further be remarked, that the business of the ministers of the gospel, the appointed teachers of religion, is vastly important. They ought always to be examples to their flocks, and carefully to exhort them, not only to fear God, but to obey those in authority. The former will readily be granted by all. Can the latter be questioned unless it be by mere partisans? As the apostle in his epistle to Titus expressly says: “Put them in mind to be subject to principalities and powers: to obey magistrates.” 58

The different modes of expression, principalities, powers and magistrates, when compared with other passages of scripture, may be considered, as comprising the officers of government, the various parts of a constitution and the variety of existing laws. A due regard is to be paid to each. So long as those in authority, are ministers of God, for good, passive obedience and non resistance are the indispensible duty of subjects, but it is far otherwise, when rulers, unmindful of the rights of the people, are unjust, oppressive and cruel.

There was particular need, of the foregoing injunction in the days of the Apostles from the great scandal brought upon religion, by the undutiful carriage of some servants and subjects, towards their masters and magistrates, by reason of the false notions of Christian liberty, advanced by the false Apostles, judaizing Teachers and Gnostic libertines.

The most ancient heretics affected to take the name of Gnostics to themselves, as expressive of that new knowledge, and extraordinary light, to which they made pretensions.

As we live in an age, in which there are a multitude of new Philosophists, who are teaching doctrines, which tend to subvert order, morality and religion, indeed to brutalize the world, some of whom are scattered through our own country, whose libertine sentiments and licentious practices tend to poison society, and to weaken government, ministers of the Gospel ought to pay very special attention, to the forecited, apostolic injunction.

The Government of this State is a happy medium, between a monarchy and democracy. The most happy government, taking all things into view, of any upon earth. The persons, property, reputation and lives of men, are by law protected. They have liberty of worshipping God, according to the dictates of their own consciences, and of doing all the good in their power. What wise and good man can wish for more? Occasional alterations in the laws of the State, no doubt, will often be found necessary. These may be made semiannually, or at most annually. A radical change is most seriously to be deprecated.

Notwithstanding the preceding observations, the chief business of ministers, is to teach the doctrines of religion, and to persuade sinners, by the terrors of the Lord, to repentance, faith and a pious walk: “To be ready to every good work. To speak evil of no man, to be no brawlers, but gentle, shewing all meekness unto all men.” 59 What need of piety, talents and fidelity! An Apostle said, “Who is sufficient for these things?” It is thought to be a great affair, to negotiate the important concerns of a State, at a foreign Court. How important then, to transact business for Christ, with the souls of men!

As important as the business of ministers is, they are, “earthen vessels.” God in his holy providence the last year, Fathers and Brethren, by the removal of one from the vineyard, 60 has taught others the vast importance, of working while the day lasts!—Those who are “faithful to the death, shall receive a crown of life.” 61

As, that people is happy whose God is the Lord, It is of vast importance to close this discourse, by observing to this large assembly, that it is necessary for every man to be truly religious, who would be really and lastingly happy. It never can be effected without, by all the efforts of ministers of the gospel, legislators and executive officers. He that would be happy, must be wise for himself, and live for eternity.

The wealth and glory of this world, are in their nature unsatisfying and fading. They never can make men happy. Those who seek for happiness from them, continually cry, who will show us any good, but never have enough. Like the two daughters of the horse leech, they say, give, give”; 62 and often, when in the full tide of prosperity, and when they least expect it, “Riches certainly make to themselves wings and fly away as an eagle towards heaven”! 63 Honour is equally precarious: Sometimes, as the wise man observes, “folly is set in great dignity, and the rich sit in a low place. I have seen servants upon horses and princes walking as servants upon earth.” 64—The late vast revolutions, and the existing commotions in Europe, too well known to this assembly, to need particularizing, most strikingly evince the mutability of this world, and the amazing folly of looking for permanent felicity, from earthly enjoyments.

It is directly the reverse with true religion. That is satisfying and unfading. In the midst of the most painful changes of this world, true religion is calculated to console the mind, and to point it forward to a happier country. The best treasure of the righteous is secured to them in heaven by promise. “Who hath begotten us again unto a lively hope, by the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. To an inheritance incorruptible and undefiled, and that fadeth not away, reserved in heaven. 65 It is your father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.” 66 He who hath promised, cannot lie. He “is a rock, his work is perfect, for all his ways are ways of judgment, a God of truth and without iniquity, just and right is he.” 67 In the darkest times they have nothing to fear. Each one may say, “Behold the Lord is my salvation, I will trust, and not be afraid: for the Lord Jehovah is my strength and my song, he is become my salvation”. 68 How carefully then, should all attend to the exhortation of the wise king in Israel? “Get wisdom, get understanding: forget it not, neither decline from the words of my mouth. Forsake her not and she shall keep thee. Wisdom is the principal thing, therefore get wisdom: and with all thy gettings get understanding.” 69

If wisdom is the principal thing, it becomes us, to acknowledge with lively gratitude, the great mercy of God in the revival of his work, in some of our cities and towns in this state, and in some other parts of the United States, and of the Christian world: and to feel the most ardent desires, for a general revival of religion.—May each person in this assembly, devoutly say, “For Zion’s sake, I will not hold my peace, and for Jerusalem’s sake I will not rest, until the righteousness thereof go forth as brightness, and the salvation thereof as a lamp that burneth.” 70

Were religion generally to prevail, party spirit would cease, our political horizon brighten, and all the contending nations of the earth be hushed into peace. The wolf also would dwell with the lamb—and the calf, and the young lion and fatling together. 71

This anniversary reminds us, how fast we are carried down the current of life, and the vast importance of doing, what we have to do with our might. The transactions of the last year, and of all past years, stand sealed up, to the judgment of the great day.

Soon all earthly kingdoms, states and empires, notwithstanding their present allurements, will be awfully destroyed. “The heavens shall pass away with a great noise, and the elements melt with fervent heat, and the earth also, and the works that are therein shall be burnt up,” 72 and an entirely new state of things commence.

Infidels may imagine, that there is no world but the present. They may lull their consciences asleep in the lap of sensuality, and flatter themselves, that if they can only pass with impunity on earth, that they have nothing to fear, from a future tribunal.—Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. For he that soweth to his flesh, shall of the flesh reap corruption: but he that soweth to the spirit, shall of the spirit reap life everlasting. 73

AMEN.

Endnotes

2. “Nothing can be advanced with certainty concerning the origin of civil societies.—Some attribute their origin to paternal authority: others suppose, that the fear and dissidence, which mankind had of one another, was their inducement to unite together under a chief, in order to shield themselves from those mischiefs, which they apprehended. Some there are in fine, who pretend, that the first beginning of civil societies, are to be attributed to ambition; supported by force, or abilities.” Polit. Law, by F. F. Burlamaqui, vol. 2, page 13, 14.

48. Marshall’s His. Of the life of Wash. Vol. v. page 139, 140.

53. A person, who pretended to be a Prophet of God, sent to reform the old religion of the Persians. He retired into a cave where he composed his book, that contained his pretended revelations. Prideaux. Vol. 1, Page 220.

54. A political fraud.—Historians tell us, that an unknown woman presented to Tarquin the proud, King of Rome, nine volumes, for which she asked a considerable price: that the King being unwilling to pay so much she burnt three, and returning, asked the same sum for the other six, which being refused, she burnt three more, and then repeated the same demand, it was now found that the remaining books were the oracles of the Cumean Sybil, which being purchased by Tarquin, the woman instantly disappeared. Millot’s Elements of hist. Vol. 1, Page 325.

55. A sacred book containing their religion. It consists of three tracts: the first of which contains their moral law; the second their ceremonial; and the third delivers the peculiar observances for each tribe of Indians. Dictionary of Arts, &c. Vol. 4.

57. Men being numbered they know not how, or why, in any of the parties that divide a state, resign the use of their own eyes and ears, and resolve to believe nothing that does not favor those whom they profess to follow. Idler, Vol. 1, Page 53.

60. Dr. Hart of Preston, whose praise was in all the churches, died Oct. 27, 1808.

(1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography: