Henry Davis (1771-1852) graduated from Yale in 1796. He served as President of Middlebury College (1810-1817) and President of Hamilton College (1817-1833). This election sermon was delivered by Dr. Davis at Montpelier, VT on October 12, 1815.

A

SERMON,

DELIVERED ON THE DAY OF GENERAL

ELECTION,

AT MONTPELIER, OCTOBER 12, 1815,

BEFORE THE HONORABLE

LEGISLATURE OF VERMONT.

BY HENRY DAVIS, D. D.

PRESIDENT OF MIDDLEBURY COLLEGE.

Published by order of the Legislature.

AN

ELECTION SERMON.

ROMANS, xiii. 4.

For he beareth not the sword in vain; for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil.

At the period, when this epistle was written, Rome was sunk in gross idolatry, and her rulers were implacable enemies of the cross of Christ. The disciples of Jesus were despised and persecuted; and in many instances put to death by the most cruel and ignominious tortures.

The descendants of Abraham boasted themselves of their distinction. Because God had favoured them with peculiar privileges; had dictated to them a system of polity, both civil and religious; had anciently proclaimed himself their king; and in later times governed them by rulers of his own appointment. They arrogated to themselves exemption from the ordinances of men, and deemed it impious and degrading to submit to their authority. Many of them, after embracing Christianity, entertained still the same views and dispositions. And of the Gentiles, also, who had renounced their idols and devoted themselves to God, there were not a few, who vainly contended, that the spiritual wisdom, with which HE had endued them, was a sufficient directory for their conduct; and that they were under no obligation to render obedience to a government, which was imposed upon them by unbelieving rulers. By these means, their dangers and sufferings were increased, and the Gospel of Christ was evil spoken of.

In this chapter of his epistle, the Apostle shews them, in a manner clear and forcible, that their principles were erroneous, and their conduct reprehensible. He begins his address, by teaching them the foundation of civil government;–that it is the ordinance of God. Not indeed that it is, as to its form, of divine appointment; but that it is sanctioned by God as essential to man, both as to the security of his happiness, and to the performance of his duties; and that its obligations are sacred and universal. Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers; for there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God.

It is no matter then, what the genius or denomination of the government, or by what means established;–what the religion of the ruler, or the religion of the subject. The obligation to obedience is ever the same; for it is founded in the will of God, and the constitution of man; and is indispensable to the being of society.

But what, it will be asked, is the measure of this obedience? Or is it to be regarded as absolute and unconditional? Does the Apostle enjoin upon his Roman brethren the doctrine of non resistance, and, by this means, legalize tyranny? Does he establish a principle so abhorrent from reason and our feelings, that men are born to be slaves? That the will of the magistrate is his only law? That subjects have no method of redress under the most grinding oppression? And that to resist the encroachments of rulers is, in all circumstances, to resist the ordinance of God?

Doctrines and principles like these, are inconsistent with every enlightened sentiment of humanity, and directly repugnant both to the precepts and spirit of the Gospel. They deliver over the multitude to the caprice and ambition of a few, and bind them in chains.

That the Roman government was, at this period, immensely corrupt, and its subjects groaning under oppression, will not be questioned. But with this matter the Apostle had no concern. It was totally incompatible with the sacred objects of his mission. An interference, in the political concerns of the state, would have awakened against the disciples of Christ a most deadly jealousy and resentment. It would have provoked a spirit of universal extermination, and brought down upon them, in a manner still more dreadful, the vengeance of the civil arm.

The founder of Christianity had expressly taught his followers that his kingdom is not of this world. The great purpose of his manifestation in the flesh was, by the sacrifice of himself, to take away the sins of the world; to reveal to man his true character and condition; to increase and to enforce his motives to duty; and to make him wise unto salvation.

While the primary and ostensible object of the Apostle, in addressing the Roman brethren in the context, was to make them acquainted with their relation to civil government, and the universal obligation of obedience to it, he indirectly, yet obviously and forcibly, teaches the magistrate the nature and extent of his authority.

Having first declared that all power emanates from God; that civil government is ordained by God; and that every soul is bound to render obedience to it; he adds, For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same. For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain. For he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil.

These considerations, it will be remembered, are urged by the Apostle on his brethren, as an additional argument for submission to the authority of the Roman magistrate. He does not attempt to shew them the character of the government under which they lived; but he teaches them plainly what ought to be its character. His meaning cannot be misapprehended. The government intended by him can be no other than a righteous government. A government which seeks the praise of God more than the praise of men; which aims steadily and inflexibly to protect and to encourage the obedient, and to chastise and to humble transgressors; which guards with equal care and solicitude the lives and privileges of all its subjects, and renders to everyone according to his character. No authority but such has God, who formed man for society, ordained to be exercised over him; and none but such can meet his approbation. If this be not the fact, the magistrate would be a terror to those who do well, and a praise to those who do evil.

The happiness of the people then is the sole object of civil government; the sole object for which anyone is invested with power, and for which he can exercise it; and the sole point, in which should centre, all his deliberations and all his exertions.

Such being the foundation of all civil institutions, of all legislative, judicial and executive authority, the conclusion is irresistible; that every nation has an unquestionable, a perfect right, to be governed by laws of its own making, and by rulers of its own choice; and that these laws and rulers it may change, as its circumstances may dictate.

And should those, who are appointed the guardians of its rights and the avengers of its injuries, trample upon the constitution; break over the boundaries of their authority, and wantonly sport with its privileges, they bear the sword in vain; they exonerate the subject from his obligation of allegiance to them, and arm him with an undoubted right to resist their aggressions. But whether resistance in a given case be expedient, circumstances must determine. If rights, essential to his security and happiness, are endangered, neither property, nor life, will be regarded in defence of them.

Every other foundation of civil government is a solecism of the grossest character, and will be embraced by none but tyrants and their slaves.

Standing on this elevated ground, invested with the sword of authority, as a minister of God for good to the people, and holding in his hand their destinies, highly interesting and responsible is the condition of the magistrate; and to trample upon the privileges of the citizens, or to sacrifice their happiness from motives of revenge, of avarice, or of ambition, is a sin of deep malignity, and cannot fail to provoke the vengeance of HIM, by whom kings reign, and princes decree justice.

In obedience to the voice of the supreme legislative authority of this commonwealth, I appear before them on this interesting occasion. God forbid that I should be unmindful of my duty, or profane the sacred office with which he hath honored me. To the character of a partisan, I disclaim all pretensions. As a member of the community, I feel, and I trust I ever shall feel, a deep interest in its welfare. But in the political questions, by which the public mind is agitated, and in which many great and good men, whom I have the honor to number among my friends, are at variance in opinion. I have no active concern. I stand in this consecrated place, as a minister of Christ, as bound by the covenant of God to deal plainly with my fellow sinners, whenever called to speak to them in HIS name, however elevated their condition.

For addressing this assembly on the duties of rulers, I need make no apology. For men of this character I am called to address. Would to God that what is to be delivered may be followed with his blessing; that it may prove useful to us all; but especially to those who are immediately concerned;–that it may excite them to fidelity in the important trust committed to them;–and that it may be found, when we shall all stand at the tribunal of God, that they have not born the sword in vain.

The language of the text is highly expressive and emphatical. The sword is introduced as an emblem of authority; and it implies that those who are invested with this authority are to exercise it with energy. But as ministers of God, as his vicegerents among men, they are not to lord it over his heritage.

Like the government of that GREAT and GOOD BEING in whose name they act, all their measures should be characterized by justice and tempered with mercy.

The necessity of civil government arises from our depravity. Had not man lost the uprightness, in which God created him, no civil restraints would have been necessary. Injustice and violence, wars and fightings, which proceed from his lusts and passions, would never have been heard of. The earth would never have been cursed with thorns and briars; and creation would still have smiled with the innocence and loveliness of paradise. But God, whose judgments are a mighty deep, and whose ways are past finding out, hath suffered man to fall from this elevated standing. The image of his Maker, which he once bore on his soul, hath departed from him. Sin hath entered the world, and confusion, and injustice, and violence are its consequences. To shield mankind, as far as possible, from these evils is the great end of all civil associations. And Christians who are called to bear the sword, are under sacred obligations, as ministers of God,

I. To make his word the guide of their conduct. The will of God is the only unerring rule of righteousness; and nowhere, excepting in his word, is HIS will clearly and satisfactorily revealed to us. Revelation is a transcript of the perfections and purposes of that ALMIGHTY and GLORIOUS BEING, who is the creator, the upholder, and the governor of all things.

In the word of God, and here only, are we taught the true origin, the real condition, the real character, and the high destiny of man. It is here, and nowhere else, that we are taught, with certainty, the nature of those capacities which God hath given him; that he is a being of other hopes than those of the present life; that he has interests, hereafter to be realized, whose value no calculation can reach; and that his residence on earth is the only season allotted him, for securing those interests. We here learn, that rulers, however exalted their talents and their rank, have the same infirmities, the same propensities and the same interests, as other men; that as moral beings their elevation entitles them to no prerogative; and that they are equally bound to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with God. Do unto others as you would they should do unto you, is a command of universal authority, and not less obligatory on the magistrate, than on the citizen. Saith the voice of inspiration, He that ruleth over men should be just, ruling in the fear of God.

When the righteous are in authority the people rejoice; but when the wicked bear rule, the people mourn.

Were the precepts of the Gospel universally regarded by rulers, and its spirit imbibed by them, vastly different would be the condition of mankind. It is granted, that among pagan nations, there have been men of exalted views and sentiments; men, who have postponed to their country’s good all private considerations; who have undauntedly faced danger and death, and cheerfully sacrificed their all to its honor and security. And it is not to be disputed, that in countries also, where Christianity has diffused its blessings, many have been found of a similar character; notwithstanding they denied its authority, and rejected its instructions.

But how many Alexanders, Caesars, and Caligulas, has the world witnessed, to one Titus, or Marcus Aurelius? And how many Neroes and Frederics of Prussia, to one Alfred, or to one Washington.

Infidelity is overreaching, overbearing and hard hearted. Its own aggrandizement is its only object. It wantonly sports with the dearest interests of society; and is prodigal of the blood of man, as of no value, when set in competition with its unhallowed desires.

Banish from the mind those solemn truths, with which revelation presents us, and all enquiries, respecting the future, are perplexed with doubt and uncertainty. Every tie of conscience, which should bind man to his duty, is sundered. Earth becomes the limit of his desires, and self promotion the centre of his exertions. And unless restrained by the fear of God, in proportion as his opportunities for subserving his own interest are increased, in the same proportion, is his danger also, of being given up to the control of such motives. Is the correctness of these remarks doubted? Let them be tried by the records of ages. How happens it, if this ignorance, or forgetfulness, of God and our duty, and this devotion to our own interest be not the cause, that the history of nations is little else than a history of revolutions of rimes and of cruelties?

How happens it, that the multitude have been the slaves of a few; that in obedience to the authors of these changes and sufferings, they have yielded up as a sacrifice, their peace, their fortunes, and their lives? And, indeed, for what other reason is it, that almost every family in Europe is now setting in sackcloth, and that her hills and her plains are one field of blood?

But let conscience, enlightened by revelation, perform its office; let rulers keep in view the commanding truths of the Gospel; let them remember that they are ministers of God; that they are accountable to HIM;–that they are entrusted with power, not to harass, to oppress, and to enslave; but to promote the peace, the virtue, and the happiness of their people; let them bear in mind the judgment to come, and the retributions of eternity; and they will have before them motives to duty that are always binding, always operative. Truth and righteousness become the pole-star of their actions; and the fascinations of power, the emoluments of office, the pomp of triumphs and of victories, and the splendors of crowns, and of diadems, vanish into nothing. It must be acknowledged, that God hath not, in his works, left himself without witness; that the honest enquirer, be his condition what it will, may, from this source, learn much of his duty and interest. But shall be for this reason reject the instructions of revelation? Would not the mariner justly be thought a mad man, who should throw into the deep his compass and chart, and be guided only by the signs and stars of heaven?

II. It is the duty of rulers to establish such laws and regulations, as are adapted to the genius and circumstances of the people.

To give strength, and peace, and security, to the community will be primary objects with every benevolent and enlightened legislator.

But these objects cannot be accomplished, without a knowledge of mankind, in general, and of the characters, relations, and necessities, of the governed, in particular. A fundamental truth in legislation is, that man, find him where you will, is a depraved being; and governed by motives, which often lead him to sacrifice the rights and happiness of others to his own interest. In consequence of rejecting this truth, or of not acting under the conviction of it, men of high distinction in intellect and attainments, have, when writing on the subject of laws and government, fallen far short of the expectations, which their talents had excited. Not regarding man as he really is, but assuming it, as a first principle, that he is rather what he ought to be, their systems, plausible enough in theory, have proved defective in experiment; and have soon sunk, with the authors of them, into neglect and oblivion. In every government, not cursed with tyranny, where men are left to think, and to act, for themselves, wise rulers, in all their measures, will be influenced by a reference to public opinion; and this opinion, it will be remembered, is, usually regulated by public interest.

The physical strength resides in the people; and whenever they are sensible of their power, and have opportunity to exert it, it is in vain to attempt to enforce laws upon them, however wise and salutary, which, in the view of the majority, are incompatible with their interests. I would by no means insinuate that this remark is universally true. I acknowledge that there are some honorable exceptions. I should rejoice were there more. But, as a general remark, it is fully attested by experience, and will not be questioned.

Many writers, far from being contemptible in understanding and in their acquirements, and who had spent much of their time in discussing the science of government, seemed to have imagined, that the views, the desires and the pursuits, of men, and the motives that actuate them, are, in all places, like the laws of the physical world, uniform and invariable; that a constitution adapted to the genius and circumstances of one nation, might, with equal propriety, be applied to any other; that the philosophers of Europe may form laws and regulations, for the aborigines of Asia, or of America, with the same confidence of success, as when attempting to account for the variety of their complexions, or of the climate and productions of their countries.

No principle is, in theory, more deceptive, and few have proved, in experiment, more mischievous. Although man, in every condition of society, is a being of corrupt propensities, and must be governed by restraints, yet, it is not to be forgotten, that every nation have their peculiarities; their own habits of feeling, of thinking and of acting; their own passions, their own interests, their own arts and employments; and the man, who attempts to legislate for any people, without a reference to this fact, will legislate in vain.

With a conviction of these truths, the prevention of crimes, by the establishment of salutary laws, will, in the view of every humane and intelligent government, be a primary object. But as men, abandoned of principle, will be found in every community, whom no threats will intimidate, and who cannot, by any vigilance and foresight, be effectually prevented from preying upon the innocent and defenceless; from disturbing the tranquility of the public, and endangering its security; it will ever be found necessary to restrain them by punishment. Examples must be made of transgressors, and be held up, as a terror, to those who would do evil.

With reference to this subject, the philanthropist looks, with emotions of regret, on the generations that are past. While he sees the arts and sciences improving, and the condition of man, in almost every other respect, gradually meliorating, it is with surprise, he perceives, in the methods of inflicting punishment, little improvement attempted, and little or no melioration, taking place.

The consequences of punishment, as they affect the future conduct of the offender, seem scarcely to have been regarded. Nothing appears, in general, to have been thought of, but the infliction of suffering, as an example to others; and the penalties inflicted have obviously been, in most instances, of such a character, as tend directly to make the subject of them more the servant of iniquity.

To expose the criminal in the stocks, or in the pillory, to the ridicule, the contempt, and the insults of the populace; or to punish him publicly at the post, and to send him away writhing and bleeding, from the stroke of the lash, can have little other effect, than to provoke a spirit of revenge; to destroy whatever sense of shame, or regard for character, might have been remaining; and to harden him for acts of deeper guilt. But to stigmatise him, by branding, or cropping, and to send him forth into the world, like Cain from the presence of God, with a mark set upon him, declaring to all men, that he is an outcast from society, a villain, and never to be trusted, is placing him, at once, beyond the reach of all honest employment; consequently beyond the power of reformation; and compelling him to continue in the commerce of iniquity, and to remain a curse to society.

More correct and exalted views of this subject were reserved for our times; and the improvement which it has already received is, by no means, the most inconsiderable of the improvements, in which we have so much occasion to rejoice.

The method, which has been recently adopted, by some governments, of punishing criminals by confinement and labor, is a happy alleviation of the criminal code, and promises much good. Indeed, much good has been already produced by it. Considered merely as an example, as a terror to those who do evil, it has, I apprehend, a more powerful influence, than the expedients that have been usually resorted to. To the man hardened in the career of wickedness, hardly anything is more dreadful than solitude; where there is no human being to commune with, but himself, and where his vices and his crimes, in spite of every effort to prevent it, will pass in review before him. But in regard to the reformation of the offender, and to the good of society, there is no ground for comparison, as to the consequences. Corporal punishment has little other tendency than to confirm the criminal in transgression; while confinement for a season, at least, frees the community, from his crimes and example, and furnishes some reason for hope of his being restored to it, at length, a sound and useful member. Without deliberate and serious reflection upon his life, there are no hopes of his amendment; nor is a conviction of his folly and guilt likely to prove effectual, without long habituation to industry, and to a course of regular conduct. Long established habits must be supplanted, and new ones formed, before a reformation can be regarded, as complete and permanent. Confinement and labor afford, in the best possible manner, both these means of amendment.

This method is farther recommended, by the fact, that the criminal may here be furnished, with moral and religious instruction, with which it is evidently the duty of the government to furnish him; that his motives to industry may be increased, by granting him some portion of the avails of it; and that for his good conduct, he is presented with the encouragement of going again into the world, with a useful trade, and with an amended character. Were this expedient of punishment and reform universally adopted, and faithfully executed, there would, in my opinion, be strong grounds to hope, that one prolific source of evils of a very dangerous tendency, which now infest society, would, ere long, well-nigh cease to exist. I say faithfully executed;–for there is much reason to apprehend, that it may not prove effectual, by rendering the confinement of shorter duration, than is necessary to produce a permanent change of habits.

But let not rulers forget, in their zeal for reformation, that the dungeon and the gibbet are not to be abandoned; that villains will exist, in every community, of so hardened and daring a character, that no other means will intimidate them; and that deeds of such extreme malignity will be perpetrated, as render forbearance foolishness and mercy a crime.

III. It is the duty of those, who are entrusted with the care of the state, to diffuse useful knowledge among their subjects.

“In arbitrary governments,” saith a writer, “The more ignorance, the more peace—but intelligence is the life of liberty.” We have reason to thank God, that we live in an age in which the truth of this assertion will not be controverted.

The encouragement of those arts and improvements, which are calculated to increase the means of subsistence, and to give vigor, and independence, and respectability, to the body politic, should embrace the attention of every government. But the instruction of the mass of people, in what is essential to their comfort, and to their characters also, as industrious, peaceable, and useful citizens, cannot, I conceive, be neglected, but with high criminality.

It is in vain for rulers to urge, as an excuse, that it is the duty of parents to educate their children. Parents, who are ignorant, it must be remembered, are too apt to be satisfied that their children should remain so. Not knowing by experience the blessings of education, they are, in general, willing, that they should grow up in the same want of information, in which they have grown up, and inherit the same vices and wretchedness, which they themselves have been heirs too. Little can ordinarily be expected, from the exertions of individuals, whatever be their patriotism and liberality.

Unless those, therefore, who are the constituted guardians of the public interests, shall extend a fostering hand to this subject, we have much reason to fear that a people, who are once ignorant, will, generation after generation, continue to be ignorant. What must be the consequences, experience tells us; indolence and vice, and poverty, and crimes, of the most destructive tendency. Those who know not their duty, and their interest, know not, of course, how to estimate them; and without a due estimation of them, it is not to be expected that they will pursue them. Men of this character are always exposed to the intrigues of every aspiring demagogue, and may easily be rendered the instruments of turmoil and violence. And history distinctly informs, that this class of the community, under the direction of ambitious and unprincipled leaders, have acted no inconsiderable part in the revolutions which have agitated and distressed the world.

Let no man deny, then, that it is the duty of government to assume the superintendence of a subject of such vital importance to the public; that it should require of those, who are able to do it, to educate their children; and should provide for the education of those, whose parents are not able, at the expense of the State.

IV. It is the duty of rulers to guard and to improve the morals of the people.

In governments strictly absolute, where the will of the despot is law, and physical power the only arbiter of every question, this subject will be regarded as of little value. It may, indeed, be presumed, that the corruption of morals is, sometimes, the principal basis on which such a government rests. But not so in countries that are blessed with freedom. Good morals are the life-spring of its being. They are the pillars, on which the constitution rests. Remove them, and it falls to ruin. Corrupt the citizens of any state, not bound in chains of tyranny, and confusion and anarchy ensue; and they soon become fit for nothing, but the minions of a despot, or the slaves of arbitrary power.

Every vice is, in its nature, degrading and dangerous. But the vices, which are most degrading, and most fatal to the public welfare, and which most imperiously demand the restraints of government, are drunkenness, profane swearing, and Sabbath-breaking. For to one, or to another of these, almost every other corrupt practice, or crime may be traced, as its origin.

Intoxication stupefies the intellect; blunts the moral perceptions; breaks down, or weakens the barriers between right and wrong; degrades and brutalizes the whole man; and renders him, ordinarily, a judgment to himself. It destroys the peace, the comfort, and the character of his family. It begets wrangling and hunger, and nakedness. Upon his wife, once the object of his tender affections, to whom he is bound, by the vow of his God, to furnish support, and to administer consolation, it brings disgrace, and shame, and despair. It leaves his children, the fruit of his own loins, to grow up, without discipline, without instruction and without example, to walk in his steps, and to be partakers of his end.

On the community also, its influence is not less to be dreaded. It disturbs the peace of neighbors. It produces among them quarrels, and lawsuits, and violence. Like the pestilence that walketh in darkness, it spreads around its contagion, and corrupts, by a gradual and almost imperceptible progress, numbers, who viewed themselves as proof against its influence; ‘till, at last, they yield themselves to its dominion, and become a curse to society. What are the vices and crimes, for which they are then not prepared, I dare not attempt to say.

Profane swearing, of all the vices that disgrace the human character, is the most silly, the most contemptible, and the most inexcusable. For there can be no possible temptation to it. Were it silly, and contemptible, and without excuse merely, we might bear with it. But it possesses other traits of character, and such as cannot be contemplated without deep alarm. To treat with habitual levity and irreverence the name of that infinitely GREAT and GOOD BEING, in whom we live, move and have our existence, and who is constantly shedding around us such a profusion of blessings, is sinful in the extreme, is searing to the conscience, and dangerous to the dearest interests of the community. God is infinitely amiable, and infinitely lovely; and that they love him with all their soul, with all their mind, and with all their strength, is his first command to all his intelligent creatures. It was disobedience to this command which filled heaven with disorder, and made this once peaceful and happy world a region of suffering, and the shadow of death. Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain;–and what art thou, presumptuous worm of the dust, that thou shouldst contemn his authority, insult him with mockery and challenge the vengeance of the Majesty of Heaven? Were thy imprecations answered, what would be the doom of thyself and of thy fellows?

But he swears for the want of reflection, says his apologist. No harm is intended by him; and notwithstanding this blemish in his character, he still has many virtues.—That the man habitually profane has virtues, if the Gospel be our guide, I seriously doubt. That he may still have amiable qualities, and be, in many respects, a good citizen, I shall not deny.

But what is this want of reflection? When habits are once formed, we may commit any crime for want of reflection. The high-way robber assassinates the traveler, for want of reflection. The man, who makes gold, or honor, his God, may murder his neighbor, his friend, for want of reflection. And let me add, that, for want of reflection, the wretch, who is a slave to his passions, may plunge the fatal knife into the heart of his parent, of his child, or of the wife of his bosom.

Want of reflection is, in most instances, the incipient step, in every species of transgression. And the man who can deliberately, or thoughtlessly blaspheme his God, and invoke his curses upon himself or his fellow men, has not, it is to be feared, taken barely the first, the second, nor the third step, towards perjury.

Destroy the sanctity of the juror’s oath, and where are we? What security remains for our property, our reputation, or our lives? You free men from the restraints of conscience; you let them loose upon each other to harass and to destroy; and you render the earth which we inhabit a theatre of violence.

Ye ministers of God, who bear the sword! See then that those over which you have authority, venerate the name of that GREAT and TERRIBLE BEING, from whom your authority is derived. Slumber not on your seats; regard not, with indifference, a sin which cries to heaven for vengeance, and threatens to undermine the very being of the community. And let no man, who is habitually profane, boast of his love of country. For in the words of Rush, 1 “A profane and swearing patriot is not a less absurdity, than a profane and swearing Christian.”

The Sabbath, were there no world but this, is the most salutary, the most important, of all institutions. It is the grand palladium of everything valuable among men. Without it, good morals never have existed, and never will exist. To the utility of the Christian Sabbath, even infidels, have, and almost with one voice, been constrained to bear testimony. It is an institution highly propitious, both to man and to beast. Wherever it is sacredly regarded, more labor will be performed, and more real good produced, by the same number, possessing equal strength and opportunities, than where it is devoted wholly to secular pursuits. For arguments, in support of the importance of this subject, let us appeal to universal experience; and the instructions which it gives never will deceive us.

Where do you find, in the records of ages, a society or nation, who have not known, or have not venerated, the Sabbath, that have long remained peaceful, happy, or independent?

It is granted, that princes, professing themselves Christians, have been tyrants. That the religion of Jesus, in itself, gentle, benignant, and merciful, has, frequently, in the hands of aspiring men, been made a patron of ignorance and an engine of oppression. But no instance can be named, where the Sabbath has been regarded agreeably to the design of its author, in which it has not alleviated his sufferings, and exalted the condition of man.

Go into any village or society, where this day is kept by all, from the master to the servant, holy unto the Lord—Mark the indications of providence, of industry, of thrift and of plenty, that are everywhere visible. Let the observance of the Sabbath be banished from among them. Let but the present generation have passed away;–and then visit them again, and mark the contrast.

The church of God, once neat and entire, now sinking to ruin, its doors fallen from their hinges, its walls defiled and broken, and, instead of resounding with the praises of Jehovah, echoing with the lowing of the beast, or with the voice of the swallow, presents a striking miniature of the change which has taken place.

The tavern, formerly the quiet and peaceful retreat of the traveler, has become a scene of noise, of riot, and of wrangling.

Listen to the curses and the impious oaths of children, as you walk the streets. See neighbors quarrelling, and harassing each other with lawsuits; their fences broken down, their fields overrun with weeds and briars; their habitations decaying; their foundations tumbling from beneath them; their windows filled with tattered garments and everything around them, like the language and persons of their wretched occupants, exhibiting the marks of idleness, of indigence, and of degeneracy. Shall not the magistrate then, who is placed as a guardian over the members of the State see to it that they Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy. But since the Sabbath will not be venerated, unless religion in general be encouraged and supported,

It is the duty of rulers,

V. To give encouragement and protection to all the interests of religion.

Divest the Sabbath of its sacred character; let it be viewed merely as a civil institution, and its salutary influence would be no longer felt. Banish the fear of God, and it would be regarded if regarded at all, only as a day of amusement and dissipation.

No man can view, with greater abhorrence than I do, the idea of an alliance between church and state. To make religion an engine of civil power; to enlist it in the cause of worldly policy and ambition, is a gross profanation of its character, and tends directly and powerfully to render it, instead of being the richest blessing, a source of oppressive evils to mankind. But that religion and civil government have no concern with each other, is a doctrine to which I can never subscribe. I can as readily admit that there is no connexion between honesty, temperance and veracity, and civil government.

The truth is, there is a vital connection between them; for neither, without the other, can have an existence that is worth a name.

What would be the religion of any people, if they had no civil government; or what their civil government, if they had no religion?

Let God and his providence be erased from the mind; let men cease to remember that his eye is constantly upon them; that he will one day judge the world in righteousness; that, on that occasion, their most secret thoughts, as well as their actions, will be brought to light, and everyone receive a just recompense of reward; and where would be the ground of confidence, between man and man? What security would be left for honor and veracity? What would become of the obligation of promises and oaths, on which, everything stable in life is depending?

Will it be argued, that our regard for the pubic good, that our innate sense of right and wrong, would be sufficient to constrain us to truth, to justice, and to benevolence? What is the public good? What are right and wrong, in the view of him, who hopes, or fears, noting beyond death? Whose creed is, Let us eat and drink for tomorrow we die?

Release mankind from the obligations of religion, and every ruler necessarily becomes a despot, and every citizen a slave. For nothing, in such circumstances, will awe men to obedience, but the iron arm of arbitrary power.

The importance of religious restraints, to the existence of civil government, has been felt by rulers in every age. To give veneration to their characters, and stability to their institutions, they have impiously, and not unfrequently, claimed kindred with their gods, and arrogated the honors of divinity. And never, until our own times, has the attempt been made to establish and support a government, without the belief and acknowledgement of a superintending power. What the consequences were, we have all witnessed.

Will it be asserted, that religion is a concern merely between man and his God, and that the authority of the state has no right to interfere in this concern? But is it not a concern also, between every man and his neighbor; between every husband and his wife; between every parent and his child; between every master and his servant; and between every magistrate and the citizen? What are the relations of men, in which it does not enjoin duties to be performed, and which, if its authority be regarded, it does not affect, control and regulate? Of all the subjects presented to the human mind, it is the most interesting, the most sublime, and the most awful. It is the only consideration, which sets before us motives that are always operative. Which, even in the darkness of midnight, and the secrecy of solitude, have their influence.

Establish the principle, that religion is a matter of no concern with civil government; exempt the former from the authority of the latter, and you establish a principle, which may prove fatal to the best regulated community on earth. You place within the reach of every fanatic, and of every man void of the fear of God, a dagger, with which he may stab society to its vitals.

Men, when under the influence of zeal without knowledge, may embrace any opinions, however absurd, or adopt any practices, however irrational, or however dangerous to the general good. Scarce a doctrine can be named, be its absurdity what it may, that fanatics have not embraced. For conscience sake, they have declared all civil restraints a gross imposition, a wanton violation of their inborn rights, and have forcibly resisted the authority of the state. For conscience sake, they have scattered around them fire brands, arrows and death! And verily thought they were doing God service. With a view to their salvation, the world has beheld, astonishing as it may seem, a combination of men, for the avowed purpose of murder, that they might be condemned and executed by the civil authority; absurdly believing, that if the time of their death were known to them with certainty, they should be constrained to repent. If the government of the state has no concern with religion, how are such extravagances to be checked? Conscience, whose dictates are urged in justification of their opinions and conduct, is, in the view of such men, the voice of God speaking within them. And will you, say they, insult its authority? Will you disregard the injunctions of this heavenly monitor?

Let it never be forgotten, that the public good is paramount to every other consideration. That no private opinions, no private interests, are to be admitted in opposition to it. Civil rulers are invested with supreme authority, for the express purpose of determining and accomplishing what is necessary to promote the peace and prosperity of the community. And shall it be aid, that these nursing fathers of the state have no control of a subject, which, in the hands of fanatics, or of men void of principle, may prove fatal even to the being of society? That it is not their duty to provide for the protection and for the support of religion, which involves in it the highest interests of man, in this life, and everything worth hoping for, in the next?

I wish to be distinctly understood on this subject. I advocate no religious establishment, by the authority of the State; the preference of no denomination of Christians;–the exclusive promotion of no society of men, be their doctrines, or their modes of worship, what they may. Let the rights of conscience, properly so called, be scrupulously, and sacredly regarded. Let every man be left to worship God, if his worship contravene not the rights of others, in the manner which his judgment shall dictate; and let no man be constrained to worship him. The public welfare demands no such partialities;–no such sacrifices;–no such constraint. Religion, as a matter of practice, has its seat in the affections; it is an exercise of the heart. Its offering, to be acceptable unto God, must be a pure, a voluntary offering—No extraneous force can excite in the soul emotions of piety, or elicit from it, the expressions of gratitude. But let the magistrate take care, that religion be respected;–that laws be enacted for the encouragement and aid of its instructors;–that every man be required, as he hath ability, to do something for the support of an object, with which his own, and the best interests of all are intimately connected;–and that the Sabbath be not profaned, by amusement, by pleasure, or by business. As minister of God for good to the people, it is his indispensible duty to do this. And the government which neglects this duty cannot fail to provoke his displeasure; and will sooner or later experience it, in the licentiousness, the factions, and the violence, which will ensue.

Will anyone, in his senses, pretend, that to be obliged to contribute to the encouragement of religion because he feels no veneration for it, or embraces not its doctrines, or to abstain from secular pursuits on the day of the Lord, is an infringement of the rights of conscience? Will anyone say, that there is anything immoral in such submission?

The man, who is, in opinion, opposed to the constitution, may, with equal propriety, refuse obedience to the authority of the state. Or the miscreant, who loves his money better than his country, or his soul—may, on pretence of religious scruples, claim exemption from the taxes, that are essential to its maintenance. Conscience hs as much concern with the latter cases, as with the former. It has, indeed, no concern with either of them.

Every member of the community, whether he worship God or not; whether he embrace the obligations of religion or not; would have a recompense, for what might reasonably be required of him, for its support. Yes, if it be of any consequence to him, that his children be virtuous and happy; that they be free from examples of profanity, of idleness, and of debauchery; that society e not harassed with broils, with riots, and with violence, and that his character, his property, and his life, be secure, he would, indeed, have an ample recompense.

VI. But of no avail will be the wisest system of policy, unless the magistrate, whose duty it is, shall vigorously, and impartially execute the laws.

The laws of the state must be vigorously executed.

Certainty of punishment, where the fear of God is wanting, is the only effectual barrier against crime. Hope of impunity strengthens temptation, and furnishes additional incentives to transgression. Let the violation of established laws be connived at, or looked upon with indifference, and there is an end to all mild and wholesome discipline. This remark is equally true of every government, from the father of the family, to the prince on the throne.

Let the regulations of the domestic circle be disregarded; let the commands of the parent cease to be enforced; and disrespect, and idleness and disorder will inevitably follow.

A constitution combining the knowledge and wisdom of ages, if this vital principle of policy were overlooked in its administration, would soon be treated with neglect and contempt.

Let those, therefore, who bear the sword, be careful that the laws be enforced—when violated, that the offender be brought to justice; that their penalties be inflicted. For if suffered to be transgressed with impunity they cease to have authority, and their threatenings are in vain.

The laws must also be impartially administered.

Government is instituted for common defence and security. Every citizen has the same claim to its care and protection. That individuals, or sects of men, whose conduct, or whose opinions, political or religious, are hostile to the principles of the constitution, and subversive of the liberties of the state, are unworthy of confidence, and are to be viewed with jealousy; is not to be denied. But so long as all render a willing submission to the laws, and advocate no measures, and embrace no sentiments, which can be deemed unconstitutional, the lives, the persons, the property, and the happiness of all, are to be regarded as sacred, and as equally sacred. In such circumstances, the exercise of favoritism, in the administration of the laws; the promotion of some, and the depression of others, from motives of prejudice, of malice, of revenge, or of personal aggrandizement, is a direct violation of the principles of distributive justice, and of the ends of civil government; and it argues a shameful destitution of that magnanimity, and expanded liberality of sentiment, which ought ever to characterize the guardians of the public weal. A practice like this, let it exist under whatever form of government it may, is tyranny. In a government, which is really, as well as professedly, republican, in its constitution and measures, it cannot fail to produce alarming consequences.

I can think of hardly a greater judgment that can be sent on any people, than the curse of weak, of timid, of partial, or of temporizing magistrates. If those, who are called to the high and responsible station of guarding, and enforcing the laws, will not execute them, with energy, with fidelity, and with impartiality, there can be no security for anything. The value of property, of every comfort, of every privilege, even of life itself, is depreciated.

Such a violation of the first principles of a righteous government, is most devoutly to be deprecated. It alienates the affections of the people from their rulers, and from the constitution; it begets jealousies, and intrigues and factions;–it emboldens the monster ice, and throws open the floodgates of licentiousness;–it shakes from their very foundations the pillars of the state;–it leads directly to all the horrors of anarchy;–and, in a word, it is the beaten road to the subversion of liberty, and to the reign of despotism.

Suffer me to remark….and I can call God to witness my sincerity….that in advancing these sentiments, I have no exclusive reference to any man, to any party of men, or to any government, in our own country. I advance them because I deem them to be truths, and momentous truths. They are, indeed, eternal truths; and the ruins of nations verify them.

Cast your eyes over the map of the world. Why have so many states and kingdoms been erased from its surface? Why prowls the savage Arab over the ruins of the proud metropolis of Assyria and of Chaldea? Why does the stupid Ottoman, or riots the effeminate Italian, on the consecrated soil, where once flourished the empire of Greece and of Rome? Famed for their arts and their arms, mighty nations trembled at their power, and submitted to their dominion. “They stood on an eminence and glory covered them.”

Though dead they still speak! Though ages since, blotted from the list of nations, their catastrophe remains a solemn and eternal memento of the truth, that, where civil officers are timid, partial, ambitious, or temporizing, in the administration of the laws, personal bravery, high attainments in science, and the ablest systems of government, cannot save a people from corruption, from licentiousness, from faction, nor from final ruin.

VII. It is the duty of rulers to exhibit to those whom they are called to govern, an example worthy their imitation.

The propensity to imitation is one of the strongest propensities of our nature. It is implanted by the God who made us deep in the human breast. It affects, in no small degree, our thoughts, our speech, and our actions. Hence the truth of the remark that “We are governed more by example than by precept.”

I readily subscribe to the doctrine of the natural, deep rooted, and malignant depravity of the heart. I must subscribe to it; for it is taught me by the exercises of my own breast, by the history of all men, and by the word of God, in a manner, which I cannot question.

But is it not to the power of example also, that vice is greatly indebted for its contagious and wide spreading influence? Even the groveling and polluted wretch, who wanders the streets taking the name of God in vain, reeling with intoxication, or imprecating damnation on himself and others, notwithstanding he may do no good, is by no means to be regarded as a blank in society. The transition, from beholding crime to the actual commission of it, is easy and natural. Vice, by becoming familiar, loses its odiousness; and practices, that were contemplated with detestation and alarm, are, by being often seen, looked upon with indifference, and adopted, not unfrequently, without remorse.

Example, by slow and imperceptible advances, transforms the temperate man into a sot, the civilized man into a savage, and makes even the dastard brave. But when aided by the respect, which is naturally entertained for a parent, for an instructor, for a ruler, or for brilliant and commanding talents, it exerts an influence that knows no calculation.—On this principle it is to be accounted for, more than any other, that families, schools, and nations, so often contract the manners and habits of their guardians;–that virtues and vices so often seem hereditary;–that the conduct of an individual of distinguished intellect and attainments, if conspicuous by his excellencies, or his crimes, is so often salutary, or pestiferous, to the community;–that the stream of corruption, at first slow and silent, in its progress, at length widens, and deepens, and swells into a torrent, bearing away the character, the hopes, and the happiness of thousands.

Of all the conditions of men, that of rulers is the most responsible, the most dignified, and the most commanding. Girded with power, as ministers of God; constituted the framers of the law; the arbiters, under its authority, of the conflicting claims of their fellow citizens; and presiding over their fortunes, their liberties and their lives, they are naturally regarded with profound emotions of deference and veneration. The elevation to which they are exalted renders all their conduct visible, and gives a force to their example, which will not be resisted. Their virtues, and their vices, diffuse their influence through the community, and stamp its character in the view of surrounding nations. That people, whom God visits with the judgment of wicked rulers, cannot long remain virtuous and happy. Regulations for the restraint or prevention of immorality, enacted by vicious magistrates is nothing better than a mockery of the solemn business of legislation. And in vain do the laws lift their voice against crimes, while those who should execute them are themselves transgressors. A government, without virtue, necessarily corrupts the people, and a people without virtue, the government. Till at length, each corrupted, and corrupting, they rush together, down the current of licentiousness, into the tempestuous ocean of misrule and anarchy.

MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY…

TO be elevated to the first office, in the gift of an independent people, is a distinction, to which few can attain. It is, however, a distinction, which, by the man, who duly considers its cares, its dangers and its responsibility, will not be coveted. It is not Sir, we trust, from the views of ambition, that you have been again induced to listen to the suffrage of your fellow citizens. We have the pleasure of believing, that purer motives actuate you;–a conviction of the truth that your talents are not your own, and a readiness to employ them in the station, to which God may call you, however arduous its cares, or perplexing its difficulties. It is a truth, which ought never to be forgotten, that the higher our elevation, the greater usually are our dangers; and that the more aggravated will be our guilt, if unfaithful to our trust. But to the man, who fears God and strives to perform his duty, the most exalted condition is not without its encouragement; for if at last accepted of him, the greater will be his reward.

To instruct your Excellency, in the duties of your office, is an undertaking, in which, I have not the presumption to engage.

The best interests of a people, who have so frequently called you to rule over them cannot but be dear to you. On your exertions, in no small degree, are those interests depending.

Rising above the narrow, the embarrassing views of party prejudices and local attachments, and surveying with an expanded benevolence, a numerous and increasing community, it will, it should be expected, be the constant, the only aim of your Excellency, to promote the chief good of every class of your constituents; to give wisdom and moderation to the councils of State, and dignity and independence to the character of the commonwealth.

Elevation above our fellow men is not without its dangers. It is not in the glare of the sunshine of prosperity, that the graces, which God requires, are most apt to be cultivated. You, Sir, are not insensible to the temptations that surround you. The praise of men vanisheth with their breath; and comfortless will be the recollection of having filled the chair of State, and of having possessed, with distinction, the confidence of thousands, should you find yourself, in the end, without the approbation of God. While faithful to your country, be faithful to your God; nor neglect to seek first the approbation of Him whose favor is life, and whose loving kindness is better than life.

May your Excellency be richly endued with the wisdom which is from above. May the God of mercy grant you, in abundance, grace, peace and consolation. And when your days shall have been numbered, and your labors finished, may you hear the welcome, the transporting plaudit, Well done thou good and faithful servant; thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things; enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.

GENTLEMEN OF THE COUNCIL, AND GENTLEMEN OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

THE interests of your charge are of no ordinary value. It is not for yourselves, for your constituents, or for the present generation only, that you legislate, but for posterity. The influence of your deliberations will descend to future time, and numbers, yet unborn, may be blessed or cursed by them.

With you, Gentlemen, it rests, in no small degree, to determine, whether we shall enjoy the privilege of wise and salutary laws, and of an upright, steady and vigorous execution of them; whether we shall be blessed with good morals, with godliness and honesty, and generations to come be virtuous, independent and happy;–or whether our land shall be filled with vice, with intrigues, and with factions, and our children rise up and curse our memory.

Rich indeed is the inheritance left us by our fathers, which was purchased by their labors and sufferings, and preserved by their toil, their valor, and their prayers. Aggravated will be the guilt of not transmitting to posterity such a legacy unimpaired.

You are not, Gentlemen, ignorant, and it is presumed not unmindful, of the high importance of the concerns that are committed you; nor of the candor, wisdom and integrity, that are essential to a faithful and able management of them.

The period, at which you are entrusted, with the interests of the commonwealth, is portentous and eventful. The circumstances in which you are assembled are in many respects auspicious. Our improvements, in agriculture, in manufactures, in literature, and the sciences are rapidly advancing. The war in which we have been involved has, under the good providence of God, been brought to an happy issue; and to HIS name be our offering of undissembled gratitude. The soldier, released from his toils and dangers, again participates of domestic comforts. Our sea coast is no longer threatened by hostile fleets, nor our frontier settlements by invading armies.

Is not the present period, however, to the American who loves the dearest interests of his country, a period of deep solicitude? While, as a nation, we have been increasing in wealth and independence, is it to be denied, that we have rapidly increased also in vice and dissipation? Where are now to be found that hardihood of integrity, that veneration for the laws, that reverence for the magistrate, and that stern and unyielding opposition to licentiousness, which so strongly characterized our virtuous ancestors?

See the laws of God and of man, daringly violated; and the holy Sabbath openly profaned. See the minister of justice slumbering over his oath, and vice rioting with impunity; profane swearing and intemperance blighting, like the mildew, our national character, and threatening our fairest hopes.

The vengeance of God will not always slumber; and unless the friends of virtue and their country will gird themselves, rise in their might, and present a barrier to these dangers, let no man be disappointed, should our nation, ere long, be spoiled of its liberties, and our children become slaves.

It is to every good man a subject of sincere rejoicing, that the public are awaking to a sense of their danger. Something has already been done to stay the progress of these evils, and to ward off the judgments of God. By your exertions, Gentlemen, in co-operation with those of your constituents, much might be done; and our privileges and our posterity, might, it is to be hoped, yet be saved from ruin.

Will you ask me, in what manner your efforts should be employed in this concern? I will tell you Gentlemen; by enacting such laws, for the prevention, and discouragement, of vice, if such be not already enacted, as circumstances require; by appointing officers of justice, who are not afraid to do their duty; and dare not leave it undone; by leading, and aiding, in forming associations, for the reformation of morals, and showing, by your counsels and exertions, that you feel a deep and solemn interest in the subject; by proving to your neighbors, that you venerate the day of the Lord; and by exhibiting to them an example of temperance and moderation by abstaining from the use of ardent spirits in all cases, excepting when necessity demands them. The use to you may be immaterial, but the example to them may be of infinite moment.

Possessing, as is evident you do, the confidence of your fellow citizens, the effect of your exertions is not to be doubted. And tell me, Gentlemen, dare you, as Christians, or as patriots, withhold your hands from this work of reformation?

But there is an evil, to which we are exposed, and which, if possible, is still more alarming. That there are within our country, men, who owe to it their birth and education, who would cheerfully sacrifice, at the shrine of their ambition, its liberties and laws, is a truth, which, though painful to contemplate, we are constrained to acknowledge. For such men, have ever existed, in every country.

But is it possible, that the citizens of these United States are, almost without exception, hostile to their government, and enemies to the soil, which was purchased by the dangers and sufferings; which was consecrated by the blood; and in whose bosom are entombed the ashes of their fathers? If this assertion be true, degenerate indeed is our character; if it be not true, we are our own gross calumniators.

But the assertion is not, cannot, be true; and the conduct of those who make it gives the lie to it. For while the adherents of the two great political parties among us are stigmatized by each other with the epithet, enemies to their country, do they not as neighbors, treat each other with confidence, and as if, on all subjects, politics only excepted, they believed each other honest? Is it possible that a man should be just, in his domestic and his social intercourse, that in his private relations, he should conduct, in the fear of God, and yet be, in his relation to the community, totally void of principle?

And to what, is the imputation of this solecism in the human character to be attributed? The answer is at hand; to party spirit, that fiend of social order; which, emerging from the abyss of darkness, has embroiled, and weakened, and prostrated the firmest governments on earth.

Examine the records of the Legislative councils of our country, for the last twenty years. Whence happens it, let me ask you, when assembled for the solemn and commanding purpose of deliberating upon its interests, and of enacting laws and adopting measures, for the public good, that we find them, day after day, week after week, and month after month, giving precisely the same number of suffrages for the affirmative and negative of almost every question; whether of a political nature or not; whether of moment or not? Whence happens it, that when an individual among them has the independence to dissent from his party, he is immediately proscribed as a traitor to their cause, and as an enemy to his country? Whence happens it, that, with every political revolution in the Legislature, well nigh every office in their gift from the supreme judicatory down to that of the most subordinate minister of justice, must change its occupant? Is it because all the talents, all the integrity, all the patriotism in the nation belong to one party exclusively? This no man dare pretend. Is it not because both are under the influence of party prejudice; a prejudice which views every objet, in relation to itself, through a disordered medium; which literally, and perhaps honestly, puts evil for good, and good for evil; darkness for light, and light for darkness; which discovers, in its opponents, no merits, but magnifies all their failings; and sees, in its friends, no imperfection, but every excellency. If, Gentlemen, those among us, of your standing and influence, will not stop and hesitate; will not, by their wisdom, their moderation, and their forbearance, endeavor to check and to stay this torrent of persecution, where, O my BELOVED COUNTRY, where will it bear you! I criminate, exclusively, neither party. But I must say, that I believe them both guilty. Perhaps they are equally guilty. I cannot contemplate this subject, but with unutterable apprehensions.

The voice of our fathers cries to us from the dead, “In vain we toiled, in vain we fought, we bled in vain, if you our sons” have not the magnanimity to immolate your prejudices, on the altar of your country’s good. Every republic, which has existed, stands a monument before us, with lessons inscribed in blood. God himself declares that A kingdom, or nation, divided against itself cannot stand.

And remember, Gentlemen, that HE also declares, though hand join in hand, the wicked shall not go unpunished. And may we all remember, that we must one day stand at his tribunal.

AMEN.

Endnotes

1 Hon. Jacob Rush, Judge of the court of Common Pleas, in the state of Pennsylvania. See his charges to the grand jury. This little book should be read by every citizen.

* Originally published: Dec. 25, 2016

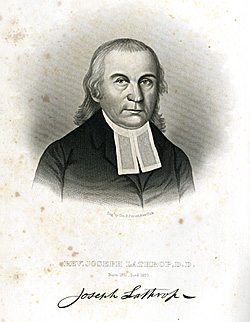

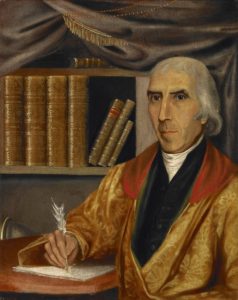

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826) Biography:

Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826) Biography: