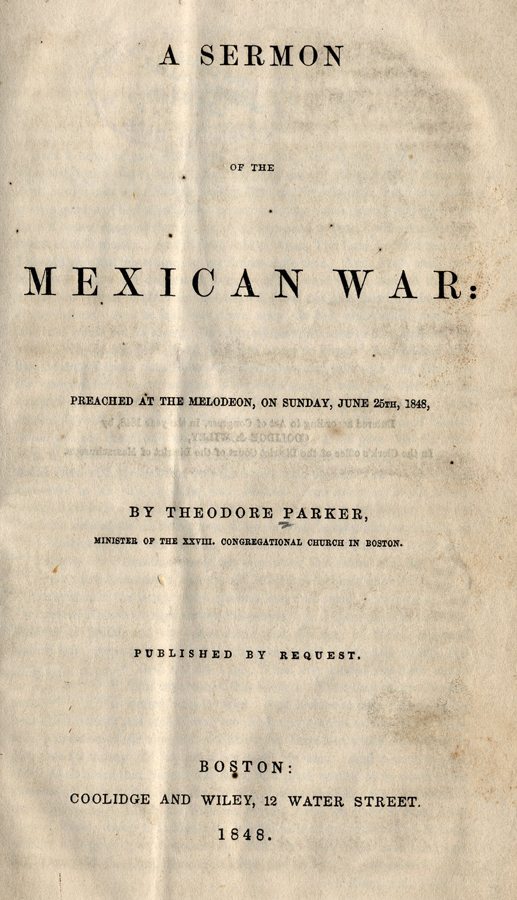

Theodore Parker (1810-1860) was the grandson of Captain John Parker, who had commanded the minute men at Lexington. He was mostly self-educated though he did some Harvard course work from home. Parker was a member of the Lexington militia, and also worked as a schoolteacher. He was a pastor in West Roxbury (1837-1846), and in Boston (1846-1852). This sermon was preached on the Mexican War in 1848 in Boston.

A SERMONOF THE

MEXICAN WAR:

PREACHED AT THE MELODEON, ON SUNDAY, JUNE 25TH, 1848.

BY THEODORE PARKER,

MINISTER OF THE XXVIII. CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH IN BOSTON.

SCRIPTURE LESSON.

OLD TESTAMENT.

And it came to pass after these things, that Naboth the Jezreelite had a vineyard, which was in Jezreel, hard by the palace of Ahab, king of Samaria. And Ahab spake unto Naboth, saying, Give me thy vineyard, that I may have it for a garden of herbs, because it is near unto my house; and I will give thee for it a better vineyard than it; or, if it seem good to thee, I will give thee the worth of it in money. And Naboth said to Ahab, The Lord forbid it me, that I should give the inheritance of my fathers unto thee. And Ahab came into his house heavy and displeased, because of the word which Naboth the Jezreelite had spoken to him; for he had said, I will not give thee the inheritance of my fathers. And he laid him down upon his bed, and turned away his face, and would eat no bread. But Jezebel his wife came to him, and said unto him, Why is thy spirit so sad, that thou eatest no bread? And he said unto her, Because I spake unto Naboth the Jezreelite, and said unto him, Give me thy vineyard for money; or else, if it please thee, I will give thee another vineyard for it: and he answered, I will not give thee my vineyard. And Jezebel his wife said unto him, Dost thou now govern the kingdom of Israel? Arise, and eat bread, and let thine heart be merry: I will give thee the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite. So she wrote letters in Ahab’s name, and sealed them with his seal, and sent the letters unto the elders and to the nobles that were in his city, dwelling with Naboth. And she wrote in the letters, saying, Proclaim a fast, and set Naboth on high among the people; and set two men, sons of Belial, before him, to bear witness against him, saying, Thou didst blaspheme God and the king: and then carry him out, and stone him, that he may die. And the men of his city, even the elders and the nobles, who were the inhabitants in his city, did as Jezebel had sent unto them, and as it was written in the letters which she had sent unto them, they proclaimed a fast, and set Naboth on high among the people. And there came in two men, children of Belial, and sat before him: and the men of Belial witnessed against him, even against Naboth, in the presence of the people, saying, Naboth did blaspheme God and the king. Then they carried him forth out of the city, and stoned him with stones, that he died. Then they sent to Jezebel, saying, Naboth is stoned, and is dead. And it came to pass, when Jezebel heard that Naboth was stoned, and was dead, that Jezebel said to Ahab, Arise, take possession of the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite, which he refused to give thee for money: for Naboth is not alive, but dead. And it came to pass, when Ahab heard that Naboth was dead, that Ahab rose up to go down to the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite, to take possession of it. And the word of the Lord came to Elijah the Tishbite, saying, Arise, go down to meet Ahab king of Israel, which is in Samaria: behold, he is in the vineyard of Naboth, whither he is gone down to possess it. And thou shalt speak unto him, saying, Thus saith the Lord, Hast thou killed, and also taken possession? 1 Kings, xxi, 1-19.

NEW TESTAMENT.Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth. Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.—

Matthew v., 3-12.

SERMON.Soon after the commencement of the war against Mexico, I said something respecting it in this place. But while I was printing the sermon, I was advised to hasten the compositors in their work, or the war would be over before the sermon was out. The advice was like a good deal of the counsel that is given a man who thinks for himself, and honestly speaks what he unavoidably thinks. It is now more than two years since the war began; I have hoped to live long enough to see it ended, and hoped to say a word about it when over. A month ago, this day, the 25th of May, the treaty of peace, so much talked of, was ratified by the Mexican Congress. A few days ago, it was officially announced by telegraph to your collector in Boston, that the war with Mexico was at an end.

There are two things about this war quite remarkable. The first is, THE MANNER OF ITS COMMENCEMENT. It was begun illegally, without the action of the constitutional authorities; begun by the command of the President of the United States, who ordered the American army into a territory which the Mexicans claimed as their own. The President says “It is ours,” but the Mexicans also claimed it, and were in possession thereof until forcibly expelled. This is a plain case, and as I have elsewhere treated at length of this matter, I will not dwell upon it again, except to mention a single fact but recently divulged. It is well known that Mr. Polk claimed the territory west of the Nueces and east of the Rio Grande, as forming a part of Texas, and therefore as forming part of the United States after the annexation of Texas. He contends that Mexico began the war by attacking the American army while in that territory and near the Rio Grande. But, from the correspondence laid before the American Senate, in its secret session for considering the treaty, it now appears that on the 10th of November, 1845, Mr. Polk instructed Mr. Slidell to offer a relinquishment of American claims against Mexico, amounting to $5,000,000 or $6,000,000, for the sake of having the Rio Grande as the western boundary of Texas;–yes, for that very territory which he says was ours without paying a cent. When it was conquered, a military government was established there, as in other places in Mexico.

The other remarkable thing about the war is, THE MANNER OF ITS CONCLUSION. The treaty of peace which has just been ratified by the Mexican authorities, and which puts an end to the war, was negotiated by a man who had no more legal authority than any one of us has to do it. Mr. Polk made the war, without consulting Congress, and that body adopted the war by a vote almost unanimous. Mr. Nicholas P. Trist made the treaty, without consulting the President; yes, even after the President had ordered him to return home. As the Congress adopted Mr. Polk’s war, so Mr. Polk adopted Mr. Trist’s treaty, and the war illegally begun is brought informally to a close. Mr. Polk is now in the President’s chair, seated on the throne of the Union, although he made the war; and Mr. Trist, it is said, is under arrest for making the treaty—meddling with what was none of his business.

When the war began, there was a good deal of talk about it here; talk against it. But, as things often go in Boston, it ended in talk. The newsboys made money out of the war. Political parties were true to their wonted principles, or their wonted prejudices. The friends of the party in power could see no informality in the beginning of hostilities; no injustice in the war itself; not even an impolicy. They were offended, if an obscure man preached against it of a Sunday. The political opponents of the party in power talked against the war, as a matter of course; but, when the elections came, supported the men that made it with unusual alacrity—their deeds serving as commentary upon their words, and making further remark thereon, in this place, quite superfluous. Many men,–who, whatever other parts of Scripture they may forget, never cease to remember that “Money answereth all things,”—diligently set themselves to make money out of the war and the new turn it gave to national affairs. Others thought that “Glory” was a good thing, and so engaged in the war itself, hoping to return, in due time, all glittering with its honors.

So what with the one political party that really praised the war, and the other who affected to oppose it, and with the commercial party, who looked only for a market—this for Merchandise and that for “Patriotism”—the friends of peace, who seriously and heartily opposed the war, were very few in number. True, the “sober second thought” of the people has somewhat increased their number; but they are still few, mostly obscure men.

Now Peace has come, nobody talks much about it; the news-boys have scarce made a cent by the news. They fired cannons, a hundred guns on the Common, for joy at the victory of Monterey; at Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, New York, men illuminated their houses in honor of the battle of Buena Vista, I think it was; the Custom House was officially illuminated at Boston for that occasion. But we hear of no cannons to welcome the peace. Thus far, it does not seem that a single candle has been burnt in rejoicing for that. The newspapers are full of talk, as usual; flags are flying in the streets; the air is a little noisy with hurrahs,–but it is all talk about the conventions at Baltimore and Philadelphia; hurrahs for Taylor and Cass. Nobody talks of the peace. Flags enough flap in the wind, with the names of rival candidates. But nowhere do the Stripes and Stars bear Peace as their motto. The peace now secured is purchased with such conditions imposed on Mexico, that while every one will be glad of it, no man, that loves Justice, can be proud of it. Very little is said about the treaty. The distinguished Senator from Massachusetts did himself honor, it seems to me, in voting against it on the ground that it enabled us to plunder Mexico of her land. But the treaty contains some things highly honorable to the character of the nation, of which we may well enough be proud, if ever of anything. I refer to the twenty-second and twenty-third articles, which provide for arbitration between the nations, if future difficulties should occur, and to the pains taken, in case of actual hostilities, for the security of all unarmed persons, for the protection of private property, and for the humane treatment of all prisoners taken in war. These ideas, and the language of these articles, are copied from the celebrated treaty between the United States and Prussia—the treaty of 1785. It is scarcely needful to add, that they were then introduced by that great and good man, Benjamin Franklin, one of the negotiators of the treaty. They made a new epoch in diplomacy, and introduced a principle previously unknown in the Law of Nations. The insertion of these articles in the new treaty is, perhaps, the only thing connected with the war which an American can look upon with satisfaction. Yet this fact excites no attention.

Still, while so little notice is taken of this matter, in public and private, it may be worth while for a minister, on Sunday, to say a word about the peace, and, now the war is over, to look back upon it, to see what it has cost, in money and in men, and what we have got by it; what its consequences have been, thus far, and are likely to be for the future; what new dangers and duties come from this cause interpolated into our nation. We have been long promised ‘Indemnity for the past and security for the future”: let us see what we are to be indemnified for, and what secured against. The natural justice of the war I will not look at now.

First, then, of the COST OF THE WAR. Money is the first thing with a good many men; the only thing with some; and an important thing with all. So, first of all, let me speak of the cost of the war IN DOLLARS. It is a little difficult to determine the actual cost of the war, thus far—even its direct cost; for the bills are not all in the hands of government; and then, as a matter of political party-craft, the government, of course, is unwilling to let the full cost become known before the next election is over. So it is to be expected that the government will keep the facts from the people as long as possible. Most governments would do the same. But Truth has a right of way everywhere, and will recover it as last, spite of the adverse possession of a political party. The indirect cost of the war must be still more difficult to come at, and will long remain a matter of calculation, in which it is impossible to reach certainty. We do not know yet the entire cost of the Florida war, or the late war with England; the complete cost of the Revolutionary war must forever be unknown.

It is natural for most men to exaggerate what favors their argument; but when I cannot obtain the exact figures, I will come a good deal within the probable amount. The military and naval appropriations for the year ending in June, 1847, were $40,865,155.96; for the next year, $31,377.679.92; the sum asked for the present year, till next June, $42,224,000; making a whole of $114.466,835.88. It is true that all this appropriation is not for the Mexican war, but it is also true that this sum does not include all the appropriations for the war. Estimating the sums already paid by the government, the private claims presented and to be presented, the $15,000,000 to be paid Mexico as purchase money for the territory we take from her, the $5,000,000 or $6,000,000 to be paid our own citizens for their claims against her,–I think I am a good deal within the mark when I say the war will have cost $150,000,000 before the soldiers are at home, discharged, and out of the pay of the State. In this sum I do not include the bounty-lands to be given to the soldiers and officers, nor the pensions to be paid them, their widows and orphans, for years to come. I will estimate that the $50,000,000 more, making a whole of $200,000,000 which has been paid or must be. This is the direct cost to the federal government, and of course does not include the sums paid by individual States, or bestowed by private generosity, to feed and clothe the volunteers before they were mustered into service. This may seem extravagant; but, fifty years hence, when party spirit no longer blinds men’s eyes, and when the whole is a matter of history, I think it will be thought moderate, and be found a good deal within the actual and direct cost. Some of this cost will appear as a public debt. Statements recently made respecting it can hardly be trusted, notwithstanding the authority on which they rest. Part of this war-debt is funded already, part not yet funded. When the outstanding demands are all settled, and the Treasury notes redeemed, there will probably be a war-debt of not less than $125,000,000. At least, such is the estimate of an impartial and thoroughly competent judge. But, not to exaggerate, let us all it only $100,000,000.

It will, perhaps, be said—part of this money, all that is paid in pensions, is a charity, and therefore no loss. But it is a charity paid to men who, except for the war, would have needed no such aid, and, therefore, a waste. Of the actual cost of the war, some three or four millions have been spent in extravagant prices for hiring or purchasing ships, in buying provisions and various things needed by the army, and supplied by political favorites at exorbitant rates. This is the only portion of the cost which is not sheer waste; here the money has only changed hands; nothing has been destroyed, except the honesty of the parties concerned in such transactions. If a Farmer hires men to help him till the soil, the men earn their subsistence and their wages, and leave, besides, a profit to their employer; when the season is over, he has his crops and his improvements as the return for their pay and subsistence. But for all that the Soldier has consumed—for his wages, his clothes, his food and drink, the fighting tools he has worn out, and the ammunition he has expended—there is no available return to show; all that is a clear waste. The beef is eaten up, the cloth worn away, the powder is burnt, and what is there to show for it all? Nothing but the “glory.” You sent out sound men, and they come back, many of them, sick and maimed; some of them are slain.

The indirect pecuniary cost of the war is caused, first, by diverting some 150,000 men—engaged in the war directly or remotely—from the works of productive industry, to the labors of war, which produce nothing; and, secondly, by disturbing the regular business of the country, first by the withdrawal of men from their natural work; then, by withdrawing large quantities of money from the active capital of the nation; and, finally, by the general uncertainty which it causes all over the land, thus hindering men from undertaking or prosecuting successfully their various productive enterprises. If 150,000 men earn, on the average, but $200 apiece, that alone amounts to $30,000,000. The withdrawal of such an amount of labor from the common industry of the country must be seriously felt. At any rate, the nation has earned $30,000,000 less than it would have done, if these men had kept about their common work.

But the diversion of capital from its natural and pacific direction is a greater evil in this case. America is rich, but her wealth consists mainly in land, in houses, cattle, ships, and various things needed for human comfort and industry. In money, we are poor. The amount of money is small in proportion to the actual wealth of the nation, and also in proportion to its activity, which is indicated by the business of the nation. In actual wealth, the Free States of America are probably the richest people in the world; but in money we are poorer than many other nations. This is plain enough, though perhaps not very well known, and is shown by the fact that interest, in European states, is from two to four per cent a year, and in America from six to nine. The active capital of America is small. Now in this war, a national debt has accumulated, which probably is or will soon be $100,000,000, or $125,000,000. Now all this great sum of money has, of course, been taken from the active capital of the country, and there has been so much less capital for the use of the Farmer, the Manufacturer, and the Merchant. But for this war, these 150,000 men and these $100,000,000 would have been devoted to productive industry; and the result would have been shown by the increase of our annual earnings, in increased wealth and comfort.

Then war produced uncertainty, and that distrust amongst men. Therefore many were hindered from undertaking new works, and others found their old enterprises ruined at once. In this way there has been a great loss, which cannot be accurately estimated. I think no man, familiar with American industry, would rate this indirect loss lower than $100,000,000; some, perhaps, at twice as much; but to avoid all possibility of exaggeration, let us call it half the smallest of these sums, or $50,000,000. This makes a whole of $250,000,000 as the complete pecuniary cost of the Mexican war—direct and indirect.

What have we got to show for all this money. We have a large tract of territory—containing, in all, both east and west of the Rio Grande, I am told, between 700,000 and 800,000 square miles. Accounts differ as to its value. But it appears, from the recent correspondence of Mr. Slidell, that in 1845 the President offered Mexico, in money, $25,000,000 for that territory which we now acquire under this new treaty. Suppose it is worth more—suppose it is worth twice as much, or all the indirect cost of the war ($50,000,000), then the $200,000,000 are thrown away.

Now, for this last sum, we could have built a sufficient Rail Road across the Isthmus of Panama—and another across the continent, from the Mississippi to the Pacific. If such a Road, with its suitable equipment, cost $100,000 a mile, and the distance should amount to 2,000 miles, then the $200,000,000 would just pay the bills. That would have been the greatest national work of productive industry in the world. In comparison with it the Lake Moeris and the Pyramids of Egypt and the Wall of China seem but the works of a child. It might be a work to be proud of till the world ends; one, too, which would advance the industry, the welfare, and general civilization of mankind to a great degree,–diminishing, by half, the distance round the globe; saving millions of property and many lives each year; besides furnishing, it is thought, a handsome income from the original outlay. But, perhaps, that would not be the best use which might be made of the money; perhaps it would not have been wise to undertake that work. I do not pretend to judge of such matters, only to show what might be done with that sum of money, if we were disposed to national works of such a character. At any rate, two Pacific Rail Roads would be better than one Mexican War. We are seldom aware of the cost of war. If a single regiment of dragoons costs only $700,000 a year—which is a good deal less than the actual cost—that is considerably more than twelve colleges like Harvard University, with its Schools for Theology, Law, and Medicine; its Scientific School, Observatory and all. We are, taken as a whole, a very ignorant people; and while we waste our School-money and School-time, must continue so.

A great man, who towers far above the common heads, full of creative thought, of the Ideas which move the world, able to organize that thought into Institutions, Laws, Practical Works;–a man of a million, a million-minded man, at the head of a nation, putting his thought into them; ruling not barely by virtue of his position, but by the intellectual and moral power to fill it; ruling not over men’s heads, but in their minds and hearts, and leading them to new fields of toil, increasing their numbers, wealth, intelligence, comfort, morals, piety—such a man is a noble sight; a Charlemagne, or a Genghis Kahn, a Moses leading his nation up from Egyptian bondage to freedom and the promised land. Now have the eyes of the world been fixed on Washington! In darker days than ours, when all was violence, it is easy to excuse such men if they were warriors also; and made, for the time, their nation but a camp. There have been ages when the most lasting ink was human blood. In our day, when war is the exception, and that commonly needless—such a man, so getting the start of the majestic world, were a far grander sight. And with such a man at the head of this nation—a great man at the head of a free nation, able and energetic and enterprising as we are—what were too much to hope? As it is, we have wasted our money, and got—the honor of fighting such a war.

Let me speak of the direct cost of the war IN MEN. In April, 1846, the entire army of the United States consisted of 7,244 men; the naval force of about 7,500. We presented the gratifying spectacle of a nation 20,000,000 strong, with a sea-coast of 3,000 or 4,000 miles, and only seven or eight thousand soldiers, and as many armed men on the sea—or less than fifteen thousand in all! Few things were more grateful to an American than this thought—that his country was so nearly free from the terrible curse of a standing army. At that time, the standing army of France was about 480,000 men; that of Russia nearly 800,000, it is said. Most of the officers in the American army and navy, and most of the rank and file, had probably entered the service with no expectation of ever shedding the blood of men. The navy and army were looked on as instruments of Peace—as much so as the Police of a city.

The first of last January, there was, in Mexico, an American army of 23,695 regular soldiers, and a little more than 50,000 volunteers—the number cannot now be exactly determined—making an army of invasion of about 75,000 men. The naval forces, also, had been increased to 10,000. Estimating all the men engaged in the service of the army and navy; in making weapons of war and ammunition; in preparing food and clothing; in transporting those things and the soldiers from place to place, by land or sea, and in performing the various other works incident to military operations,–it is within bounds to say that there were 80,000 or 90,000 men engaged indirectly in the works of war. But not to exaggerate, it is safe to say that 150,000 men were directly or indirectly engaged in the Mexican war. This estimate will seem moderate when you remember that there were about 5,000 teamsters connected with the army in Mexico.

Here, then, were 150,000 men, whose attention and toil were diverted from the great business of productive industry to merely military operations, or preparations for them. Of course, all the labor of these men was of no direct value to the human race. The food and clothing and labor of a man who earns nothing by productive work of Hand or Head, is food, clothing, and labor thrown away—labor in vain. There is nothing to show for the things he has consumed. So all the work spent in preparing ammunition and weapons of war is labor thrown away, an absolute loss, as much as if it had been spent in making earthen pitchers and then in dashing them to pieces. A country is the richer for every serviceable plough and spade made in it, and the world the richer; they are to be used in productive work, and when worn out, there is the improved soil and the crops that have been gathered, to show for the wear and tear of the tools. So a country is the richer for every industrious Shoemaker and Blacksmith it contains; for his time and toil go to increase the sum of human comfort—creating actual wealth. The world also is better off, and becomes better through their influence. But a country is the poorer for every Soldier it maintains, and the world poorer, as he adds nothing to the actual wealth of mankind; so is it the poorer for each sword and cannon made within its borders, and the world poorer, for these instruments cannot be used in any productive work, only for works of destruction.

So much for the labor of these 150,000 men—labor wasted in vain. Let us now look at the cost of life. It is not possible to ascertain the exact loss suffered up to this time, in killed, deceased by ordinary diseases, and in wounded; for some die before they are mustered into the service of the United States, and parts of the army are so far distant from the seat of government that their recent losses are still unknown. I rely for information on the last report of the Secretary of War, read before the Senate April 10th, 1848, and recently printed. That gives the losses of parts of the army up to December last; other accounts are made up only till October, or till August. Recent losses will of course swell the amount of destruction. According to that Report, on the American side there has been killed in battle, or died of wounds received therein, 1,689 persons; there had died of diseases and accidents, 6,173; 3,743 have been wounded in battle who were not known to be dead at the date of the report.

This does not include the deaths in the navy, nor the destruction of men connected with the army in various ways—as furnishing supplies and the like. Considering the sickness and accidents that have happened in the present year, and others which may be expected before the troops reach home, I may set down the total number of deaths on the American side, caused by the war, at 15,000, and the number of wounded men at 4,000. Suppose the army on the average to have consisted of 50,000 men for two years, this gives a mortality of 15 per cent. Each year, which is an enormous loss even for times of war, and one seldom equaled in modern warfare.

Now, most of the men who have thus died or been maimed were in the prime of life—able-bodied and hearty men. Had they remained at home in the works of peace, it is not likely that more than 500 of the number would have died. So then 14,500 lives may be set down at once to the account of the war. The wounded men are of course to thank the war, and that alone, for their smart and the life-long agony which they are called on to endure.

Such is the American loss. The loss of the Mexicans we cannot now determine. But they have been many times more numerous than the Americans; have been badly armed, badly commanded, badly trained, and besides have been beaten in every battle;–their number seemed often the cause of their ruin, making them confident before battle and hindering their retreat after they were beaten. Still more, they have been ill provided with surgeons and nurses to care for the wounded, and were destitute of medicines. They must have lost in battle five or six times more than we have done, and have had a proportionate number of wounded to “lie like a military bulletin” is a European proverb; and it is not necessary to trust reports which tell of 600 or 900 Mexicans left dead on the ground, while the Americans lost but five or six. But when we remember that only 12 Americans were killed during the bombardment of Vera Cruz, which lasted five days; that the citadel contained more than 5,000 soldiers and over 400 pieces of cannon, we may easily believe the Mexican losses on the whole have been 10,000 men killed and perished of their wounds. Their loss by sickness would probably be smaller than our own, for the Mexicans were in their native climate, though often ill furnished with clothes, with shelter and provisions; so I will put down their loss by ordinary diseases at only 5,000, making a total of 15,000 deaths. Suppose their number of wounded was four times as great as our own, or 20,000. I should not be surprised if this were only half the number.

Put all together and we have in total, Americans and Mexicans, 24,000 men wounded, more or less, and the greater part maimed for life; and we have 30,000 men killed on the field of battle, or perished by the slow torture of their wounds, or deceased of diseases caused by extraordinary exposures,–24,000 men maimed; 30,000 dead!

You all remember the bill which so hastily passed Congress in May, 1846, and authorized the war previously begun. You perhaps have not forgot the preamble, “Whereas war exists by the act of Mexico.” Well, that bill authorized the waste of $200,000,000 of American treasure—money enough to have built a Rail Road across the Isthmus of Panama, and another to connect the Mississippi and the Pacific ocean; it demanded the disturbance of industry and commerce all over the land, caused by withdrawing $100,000,000 from peaceful investments, and diverting 150,000 Americans from their productive and peaceful works; it demanded a loss yet greater of the treasure of Mexicans; it commanded the maiming of 24,000 men for life, and the death of 30,000 men in the prime and vigor of manhood. Yet such was the state of feeling—I will not say of thought—in the Congress, that out of both houses only 16 men voted against it. If a Prophet had stood there he might have said to the Representative of Boston, “You have just voted for the wasting of 2000,000,000 of the very dollars you were sent there to represent; for the maiming of 24,000 men and the killing of 30,000 more—part by disease, part by the sword, part by the slow and awful lingering’s of a wounded frame! Sir, that is the English of your vote.” Suppose the Prophet, before the vote was taken, could have gone round and told each member of Congress, “If there comes a war, you will perish in it”—perhaps the vote would have been a little different. It is easy to vote away blood, if it is not your own!

Such is the cost of the war in money and in men. Yet it has not been a very cruel war. It has been conducted with as much gentleness as a war of invasion can be. There is no agreeable way of butchering men. You cannot make it a pastime. The Americans have always been a brave people; they were never cruel. They always treated their prisoners kindly—in the Revolutionary war, in the late war with England. True, they have seized the Mexican ports, taken military possession of the custom houses, and collected such duties as they saw fit; true, they sometimes made the army of invasion self-subsisting, and to that end have levied contributions on the towns they have taken; true, they have seized provisions which were private property, snatching them out of the hands of men who needed them; true, they have robbed the rich and the poor; true, they have burned and bombarded towns—have murdered men and violated women. All this must of course take place in any war. There will be the general murder and robbery committed on account of the nation, and the particular murder and robbery on account of the special individual. This also is to be expected. You cannot set a town on fire and burn down just half of it—making the flames stop exactly where you will. You cannot take the most idle, ignorant, drunken, and vicious men out of the low population in our cities and large towns, get them drunk enough or foolish enough to enlist, train them to violence, theft, robbery, murder, and then stop the man from exercising his rage or lust on his own private account. If it is hard to make a dog understand that he must kill a hare for his master, but never for himself, it is not much easier to teach a volunteer that it is a duty, a distinction, and a glory to rob and murder the Mexican people for the nation’s sake, but a wrong, a shame, and a crime to rob or murder a single Mexican for his own sake. There have been instances of wanton cruelty, occasioned by private licentiousness and individual barbarity. Of these I shall take no further notice, but come to such as have been commanded by the American authorities, and which were the official acts of the nation.

One was the capture of Tabasco. Tabasco is a small town several hundred miles from the theatre of war, situated on a river about 80 miles from the sea, in the midst of a fertile province. The army did not need it, nor the navy. It did not lie in the way of the American operations; its possession would be wholly useless. But one Sunday afternoon, while the streets were full of men, women, and children, engaged in their Sunday business, a part of the naval force of America swept by; the streets running at right angles with the river, were enfiladed by the hostile cannon, and men, women, and children, unarmed and unresisting, were mowed down by the merciless shot. The city was taken, but soon abandoned, for its possession was of no use. The killing of those men, women, and children was as much a piece of murder, as it would be to come and shoot us to-day, and in this house. No valid excuse has been given for this cold-blooded massacre—none can be given. It was not battle, but wanton butchery. None but a Pequod Indian could excuse it. The Theological newspapers in New England thought it a wicked thing in Dr. Palfrey to write a letter on Sunday, though he hoped thereby to help end the war. How many of them had any fault to find with this national butchery on the Lord’s day? Fighting is bad enough any day; fighting for mere pay, or glory, or the love of fighting, is a wicked thing; but to fight on that day when the whole Christian world kneels to pray in the name of the Peace-maker; to butcher men and women and children, when they are coming home from church, with prayer-books in their hands, seems an aggravation even of murder; a cowardly murder, which a Hessian would have been ashamed of. “But ‘twas a famous victory.”

One other instance, of at least apparent wantonness, took place at the bombardment of Vera Cruz. After the siege had gone on for a while, the foreign consuls in the town, “moved,” as they say, “by the feeling of humanity excited in their hearts by the frightful results of the bombardment of the city,” requested that the women and children might be allowed to leave the city, and not stay to be shot. The American General refused; they must stay and be shot.

Perhaps you have not an adequate conception of the effect produced by bombarding a town. Let me interest you a little in the details thereof. Vera Cruz is about as large as Boston in 1810; it contains about 30,000 inhabitants. In addition it is protected by a castle—the celebrated fortress of St. Juan d’ Ulloa, furnished with more than 5000 soldiers and over 400 cannons. Imagine to yourself Boston as it was 40 years ago, invested with a fleet on one side, and an army of 15,000 men on the land, both raining cannon-balls and bomb-shells upon your houses; shattering them to fragments, exploding in your streets, churches, houses, cellars, mingling men, women, and children in one promiscuous murder. Suppose this to continue five days and nights;–imagine the condition of the city; the ruins, the flames; the dead, the wounded, the widows, orphans; think of the fears of the men anticipating the city would be sacked by a merciless soldiery—think of the women! Thus you will have a faint notion of the picture of Vera Cruz at the end of March, 1847. Do you know the meaning of the name of the city? Vera Cruz is the True Cross. “See how these Christians love one another.” The Americans are followers of the Prince of Peace; they have more missionaries amongst the “heathen” than any other nation, and the President, in his last message, says, “No country has been so much favored, or should acknowledge with deeper reverence the manifestations of the Divine protection.” The Americans were fighting Mexico to dismember her territory, to plunder her soil, and plant thereon the institution of Slavery, “the necessary back-ground of Freedom.”

Few of us have ever seen a battle, and without that none can have a complete notion of the ferocious passions which it excites. Let me help your fancy a little by relating an anecdote which seems to be very well authenticated, and requires but little external testimony to render it credible. At any rate, it was abundantly believed a year ago; but times change, and what was then believed all round may now be “the most improbable thing in the world.” At the battle of Buena Vista, a Kentucky regiment began to stagger under the heavy charge of the Mexicans. The American commander-in-chief turned to one who stood near him, and exclaimed, “By God, this will not do. This is not the way for Kentuckians to behave when called on to make good a battle. It will not answer, sir.” So the General clenched his fist, knit his brows, and set his teeth hard together. However, the Kentuckians presently formed in good order and gave a deadly fire, which altered the battle. Then the old General broke out with a loud hurrah. “Hurrah for old Kentuck,” he exclaimed, rising in his stirrups; “that’s the way to do it. Give ‘em hell, damn ‘em,” and tears of exultation rolled down his cheeks as he said it. You find the name of this general at the head of most of the whig newspapers in the United States. He is one of the most popular candidates for the Presidency. Cannons were fired for him—a hundred guns on Boston Common, not long ago—in honor of his nomination for the highest office in he gift of a free and Christian people. Soon we shall probably have clerical certificates, setting forth—to the people of the North—that he is an exemplary Christian. You know how Faneuil Hall, the old “Cradle of Liberty,” rang with “hurrah for Taylor,” but a few days ago. The seven wise men of Greece were famous in their day; but now nothing is known of them except a single pungent aphorism from each, “Know thyself,” and the like. The time may come when our great men shall have suffered this same reduction descending—all their robes of glory having vanished save a single thread. Then shall Franklin be known only as having said, “Don’t give too much for the Whistle”; Patrick Henry for his “Give me Liberty or Give Me Death”; Washington for his “In Peace Prepare for War”: Jefferson for his “All Men Are Created Equal”;–and General Taylor shall be known only by his attributes rough and ready, and for his aphorism, “Give ‘em hell, damn ‘em.” Yet he does not seem to be a ferocious man, but generous and kindly, it is said, and strongly opposed to this particular war, whose “natural justice” it seems he looked at, and which he thought was wicked at the beginning, though, on that account, he was none the less ready to fight it.

One thing more I must mention in speaking of the cost of men. According to the Report quoted just now, 4,966 American soldiers had deserted in Mexico. Some of them had joined the Mexican army. When the American commissioners who were sent to secure the ratification of the treaty, went to Queretaro, they found there a body of 200 American soldiers, and 800 more were at no great distance, mustered into the Mexican service. These men, it seems, had served out their time in the American camp, and notwithstanding they had—as the President says in his message—“covered themselves with imperishable honors,” by fighting men who never injured them, they were willing to go and seek yet a thicker mantle of this imperishable honor, by fighting against their own country! Why should they not? If it were right to kill Mexicans for a few dollars a month, why was it not right also to kill Americans, especially when it pays the most? Perhaps it is not an American habit to inquire into the justice of a war, only into the profit which it may bring. If the Mexicans pay best—in money—these 1000 soldiers made a good speculation. No doubt in Mexico military glory is at a premium—though it could hardly command a greater price just now than in America, where, however, the supply seems equal to the demand.

The numerous desertions and the readiness with which the soldiers joined the “foe”, show plainly the moral character of the men, and the degree of “Patriotism” and “Humanity” which animated them in going to war. You know the severity of military discipline; the terrible beatings men are subjected to before they can become perfect in the soldier’s art; the horrible and revolting punishments imposed on them for drunkenness—though little pains were taken to keep the temptation from their eyes—and disobedience of general orders. You have read enough of this in the newspapers. The officers of the volunteers, I am told, have generally been men of little education, men of strong passions and bad habits; many of them abandoned men, who belonged to the refuse of society. Such men run into an army as the wash of the street runs into the sewers. Now when such a man gets clothed with a little authority, in time of peace, you know what use he makes of it; but when he covers himself with the “imperishable honors” of his official coat, gets an epaulette on his shoulder, a sword by his side, a commission in his pocket, and visions of “glory” in his head, you may easily judge how he will use his authority, or may read in the newspapers how he has used it. When there are brutal soldiers, commanded by brutal captains, it is to be supposed that much brutality is to be suffered.

Now desertion is a great offence in a soldier; in this army it is one of the most common—for nearly ten per cent. Of the American army has deserted in Mexico, not to mention the desertions before the army reached that country. It is related that forty-eight men were hanged at once for desertion; not hanged as you judicially murder men in time of peace, privately, as if ashamed of the deed, in the corner of a jail, and by a contrivance which shortens the agony and makes death humane as possible. These forty-eight men were hanged slowly; put to death with painful procrastinations—their agony willfully prolonged, and death embittered by needless ferocity. But that is not all: it is related, that these men were doomed to be thus murdered on the day when the battle of Churubusco took place. These men, awaiting their death, were told they should not suffer till the American flag should wave its stripes over the hostile walls. So they were kept in suspense an hour, and then—slowly hanged—one by one. You know the name of the officer on whom this barbarity rests; it was Colonel Harney, a man whose reputation was black enough and base enough before. His previous deeds, however, require no mention here. But this man is now a General—and so on the high road to the Presidency, whenever it shall please our Southern masters to say the word. Some accounts say there were more than forty-eight who thus were hanged. I only give the number of those whose names lie printed before me as I write. Perhaps the number was less; it is impossible to obtain exact information in respect to the matter, for the government has not yet published an account of the punishments inflicted in this war. The information can only be obtained by a “Resolution” of either house of Congress, and so is not likely to be had before the election. But at the same time with the execution, other deserters were scourged with fifty lashes each, branded with a letter D, a perpetual mark of infamy, on their cheek, compelled to wear an iron yoke, weighing eight pounds, about their neck. Six men were made to dig the grave of their companions, and were then flogged with two hundred lashes each.

I wish this hanging of forty-eight men could have taken place in State Street, and the respectable citizens of Boston, who like this war, had been made to look on and see it all; they had seen those poor culprits bid farewell to father, mother, wife, or child, looking wishfully for the hour which was to end their torment, and then, one by one, have seen them slowly hanged to death; that your Representative, ye men of Boston, had put on all the halters! He did help put them on; that infamous vote—I speak not of the motive, it may have been as honorable as the vote itself was infamous—doomed these eight and forty men to be thus murdered.

Yes, I wish all this killing of the 2,000 Americans on the field of battle, and the 10,000 Mexicans; all this slashing of the bodies of 24,000 wounded men; all the agony of the other 18,000 that have died of disease, could have taken place in some spot where the President of the United States and his Cabinet, where all the Congress who voted for the war, with the Baltimore conventions of ’44 and ’48, and the Whig convention of Philadelphia, and the controlling men of both political parties, who care nothing for this bloodshed and misery they have idly caused—could have stood and seen it all; and then that the voice of the whole nation had come up to them and said, “This is your work, not ours. Certainly we will not shed our blood, nor our brothers’ blood, to get never so much slave territory. It was bad enough to fight in the cause of Freedom. In the cause of Slavery—God forgive us for that! We have trusted you thus far, but please God, we never will trust you again.”

Let us now look at the effect of this war on the morals of the nation. The Revolutionary war was the contest for a great Idea. If there were ever a just war it was that—a contest for national existence. Yet it brought out many of the worst qualities of human nature, on both sides, as well as some of the best. It helped make a Washington, it is true, but a Benedict Arnold likewise. A war with a powerful nation, terrible as it must be, yet develops the energy of the people, promotes self-denial, and helps the growth of some qualities of a high order. It had this effect in England from 1798 to 1815. True, England for that time became a despotism, but the self-consciousness of the nation, its self-denial and energy of the people, promotes self-denial, and helps the growth of some qualities of a high order. It had this effect in England from 1798 to 1815. True, England for that time became a despotism, but the self-consciousness of the nation, its self-denial and energy were amazingly stimulated; the moral effect of that series of wars was doubtless far better than of that infamous contest which she has kept up against Ireland for many years. Let us give even war its due; when a great boy fights with an equal, it may develop his animal courage and strength—for he gets as bad as he gives, but when he only beats a little boy that cannot pay back his blows, it is cowardly as well as cruel, and doubly debasing to the conqueror. Mexico was no match for America. We all knew that very well before the war began. When a nation numbering 8,000,000 or 9,000,000 of people can be successfully invaded by an army of 75,000 men, two thirds of them volunteers, raw and undisciplined; when the invaders with less than 15,000 can march two hundred miles into the very heart of the hostile country, and with less than 6,000 can take and hold the capital of the nation—a city of 100,000 or 200,000 inhabitants—and dictate a peace, taking as much territory as they will—it is hardly fair to dignify such operations with the name of war. The little good which a long contest with an equal might produce in the conqueror, is wholly lost. Had Mexico been a strong nation we should never have had this conflict. A few years ago, when General Cass wanted a war with England, “an old-fashioned war,” and declared it “unavoidable,” all the men of property trembled. The Northern men thought of their mills and their ships; they thought how Boston and New York would look after a war with our sturdy old Father over the sea; they thought we should lose many millions of dollars and gain nothing. The men of the South, who have no mills and no ships and no large cities to be destroyed, thought of their “peculiar institution,” they thought of a servile war, they thought what might become of their slaves, if a nation which gave $100,000,000 to emancipate her bondmen should send a large army with a few black soldiers from Jamaica; should offer money, arms, and freedom to all who would leave their masters and claim their Unalienable Rights. They knew the Southern towns would be burnt to ashes, and the whole South, from Virginia to the Gulf, would be swept with fire,–and they said, “Don’t.” The North said so, and the South, they feared such a war, with such a foe. Every body knows the effect which this fear had on Southern Politicians, in the beginning of this century, and how gladly they made peace with England soon as she was at liberty to turn her fleet and her army against the most vulnerable part of the nation. I am not blind to the wickedness of England – more than ignorant of the good things she has done and is doing; ¬— a Paradise for the rich and strong, she is still a Purgatory for the wise and the good, and the Hell of the poor and the weak. I have no fondness for war anywhere — and believe it needless and wanton in this age of the world, surely needless and wicked between Father England and Daughter America; but I do solemnly believe that the moral effect of such an old-fashioned war as Mr. Cass in 1845 thought unavoidable would have been better than that of this Mexican war. It would have ended Slavery; ended it in blood no doubt, the worst thing to blot out an evil with, but ended it forever. God grant it may yet have a more peaceful termination. We should have lost millions of property and thousands of men, and then, when Peace came, we should know what it was worth; — and as the burnt child dreads the fire, no future President, or Congress, or Convention, or Party would talk much in favor of war for some years to come.

The moral effect of this war is thoroughly bad. It was unjust in the beginning. Mexico did not pay her debts; but though the United States in 1783 acknowledged the British claims against themselves, they were not paid until 1803. Our claims against England for her depredations in 1793 were not paid till 1804; our claims against France for her depredations in 1806-13 were not paid us till 1834. The fact that Mexico refused to receive the resident minister which the United States sent to settle the disputes, when a commissioner was expected — this was no ground of war. We have lately seen a British ambassador ordered to leave Spain within eight and forty hours, and yet the English minister of foreign affairs, Lord Palmerston no new had at diplomacy — declares that this does not interrupt the concord of the two nations! We treated Mexico contemptuously before hostilities began; and when she sent troops into a territory which she had always possessed — though Texas had claimed it — we declared that was an act of war, and ourselves sent an army to invade her soil, to capture her cities, and seize her territory. It has been a war of plunder, undertaken for the purpose of seizing Mexican territory and extending over it that dismal curst which blackens, impoverishes, and barbarizes half the Union now, and slowly corrupts the other half. It was not enough to have Louisiana a slave territory; not enough to make that institution perpetual in Florida; not enough to extend this blight over Texas – we must have yet more slave soil, one day to be carved into slave states, to bind the Southern yoke yet more securely on the Northern neck; to corrupt yet more the politics, literature, morals of the North. The war was unjust at its beginning; mean in its motives, a war without honorable cause; a war for plunder, a quarrel between a great boy and a little puny weakling who could not walk alone, and could hardly stand. We have treated Mexico as the three Northern powers treated Poland in the last century – stooped to conquer. Nay, our contest has been like the English seizure of Ireland. All the Justice was on one side – the force, skill, and wealth on the other.

I know men say the war has shown us that Americans could fight. Could fight! — almost every male beast will fight, the more brutal the better. The long war of the Revolution, when Connecticut, for seven years, kept 5000 men in the field, showed that Americans could fight; — Bunker Hill and Lexington showed that they could fight even without previous discipline. If such valor be a merit, I am ready to believe that the Americans in a great cause like that of Mexico – to resist wicked invasion – is full of the elements that make soldiers. Is that a praise? Most men think so, but it is the smallest honor of a nation. Of all glories, military glory at its best estate seems the poorest.

Men tell us it shows the strength of the nation; and some writers quote the opinions of European kings who, when hearing of the battles of Monterey, Buena Vista, and Vera Cruz, became convinced that we were “a great people.” Remembering the character of these kings, one can easily believe that such was their judgment, and will not sigh many times at their fate, but will hope to see the day when the last king who can estimate a nation’s strength only by its battles has passed on to impotence and oblivion. The power of America – do we need proof of that? I see it in the streets of Boston and New York; in Lowell and in Lawrence; I see it in our mills and our ships; I read it in those letters of iron written all over the North, where he may read that runs; I see it in the unconquered energy which tames the forest, the rivers, and the ocean; in the school-houses which lift their modest roof in every village of the North; in the churches that rise all over the Freeman’s land – would God that they rose higher – pointing down to man and to human duties, and up to god and immortal life. I see the strength of America in that tied of population which spreads over the prairies of the West, and beating on the Rocky Mountains, dashes its peaceful spray to the very shores of the Pacific sea. Had we taken 150,000 men and $200,000,000 and built two Rail Roads across the continent, that would have been a worthy sign of the nation’s strength. Perhaps the kings could not see it; but sensible men could see it and be glad. Now this waste of treasure and this waste of blood is only a proof of weakness. War is a transient weakness of the nation, but Slavery a permanent imbecility.

What falsehood has this war produced in the executive and legislative power; in both parties – Whigs and Democrats! I always thought that here in Massachusetts the Whigs were to blame; they tried to put the disgrace of war on the others, while the Democratic party coolly faced the wickedness. Did far-sighted men know that there would be a war on Mexico, or on the Tariff, or the Currency, and prefer the first as the least evil!

See to what the war has driven two of the most famous men of the nation: — one wished to “capture or slay a Mexican,” the other could encourage the volunteers to fight a war which he had denounced as needless, “a war of pretexts,” and place the men of Monterey before the men of Bunker Hill; each could invest a son in that unholy cause. You know the rest: the fathers ate sour grapes and the children’s teeth were set on edge. When a man goes on board an emigrant ship reeking with filth and fever, not for gain, not for “glory,” but in brotherly love, catches the contagion and dies a martyr to his heroic benevolence, men speak of it in corners and it is soon forgot; there is no parade in the streets; Society takes little pains to do honor to the man. How rarely is a pension given to his widow or his child; only once in the whole land, and then but a small sum. But when a volunteer officer – for of the humbler and more excusable men that fall we take no heed, war may mow that crop of “vulgar deaths” with what scythe he will – falls or dies in the quarrel which he had no concern in, falls in a broil between the two nations, your newspapers extol the man, and with martial pomp, “sonorous metal blowing martial sounds,” with all the honors of the most honored dead, you lay away his body in the tomb. Thus is it that the nation teaches these little ones that it is better to kill than to make alive.

I know there are men in the army, honorable and high-minded men, Christian men, who dislike war in general, and this war in special, but such is their view of official duty that they obeyed the summons of battle, though with pain and reluctance. They knew not how to avoid obedience. I am willing to believe there are many such. But with volunteers – who of their own accord came forth to enlist – men not blinded by ignorance, not driven by poverty to the field, but only by hope of reward – what shall be said of them! Much may be said to excuse the rank and file, ignorant men, many of them in want – but for the leaders, what can be said? Had I a brother who in the day of the nations extremity came forward with a good conscience, and periled his life on the battlefield and lost it, “in the sacred cause of God and his country,” I would honor the man, and when his dust came home I would lay it away with his fathers – with sorrow indeed, but with thankfulness of heart, that for conscience’ sake he was ready even to die. But had I a brother who merely for his pay, or hope of fame, had voluntarily gone down to fight innocent men, to plunder their territory, and lost his life in that felonious essay – in sorrow and in silence and in secrecy would I lay down his body in the grave; I would not court display, nor mark it with a single stone.

See how this war has affected public opinion. How many of your newspapers have shown its true atrocity; how many of the pulpits? Yet if any one is appointed to tell of public wrongs it is the Minister of Religion. The Governor of Massachusetts is an officer of a Christian church – a man distinguished for many excellences, some of them by no means common; in private, it is said, he is opposed to the war and thinks it wicked; but no man has lent himself as a readier tool to promote it. The Christian and the Man seem lost in the Office – in the Governor! What a lesson of falseness does all this teach to that large class of persons who took no higher than the example of eminent men for their instruction. You know what complaints have been made, by the highest authority in the nation, because a few men dared to speak against the war. It was “affording aid and comfort to the enemy.” If the war-party had been stronger, and feared no public opinion, we should have had men hanged for treason because they spoke of this national iniquity! Nothing would have been easier. A “gag law” is not wholly unknown in America.

If you will take all the theft, all the assaults, all the cases of arson, ever committed in time of peace in the United States since 1620, and add to them all the cases of violence offered to woman, with all the murders – they will not amount to half the wrongs committed in this war for the plunder of Mexico. Yet the cry has been and still is, “You must not say a word against it; if you do, you ‘afford aid and comfort to the enemy.’” Not tell the nation that she is doing wrong? What a miserable saying is that; let it come from what high authority it may, it is a miserable saying. Make the case your own. Suppose the United States were invaded by a nation ten times abler for war than we are – with a cause no more just, intentions equally bad; invaded for the purpose of dismembering our territory and making our own New England the soil of Slaves; would you be still? Would you stand and look on tamely while hostile hosts, strangers in language manners, and religion, crossed your rivers, seized your ports, burnt your towns? No, surely not. Though the men of New England would not be able to resist with most celestial love, they would contend with most manly vigor; and I should rather see every house swept clean off the land, and the ground sheeted with our own dead; rather see every man, woman, and child in the land slain, than see them tamely submit to such a wrong – and so would you. No, sacred as life is and dear as it is, better let it be trodden out by the hoof of war rather than yield tamely to a wrong. But while you were doing you utmost to repel such formidable injustice, if in the mist of your invaders men rode up and said, “America is in the right, and Brothers, you are wrong, you should not thus kill men to steal their land; shame on you!”—how should you feel towards such? Nay, in the struggle with England, when our fathers periled every thing but honor, and fought for the Unalienable Rights of man, you all remember, how in England herself there stood up noble men, and with a voice that was heard above the roar of the populace, and an authority higher than the majesty of the throne they said, “You do a wrong; you may ravage, but you cannot conquer. If I were an American, while a foreign troop remained in my land, I would never lay down my arms; no, never, never, never!”

But I wander a little from my theme—the effect of the war on the morals of the nation. Here are 50,000 or 75,000 men trained to kill. Hereafter they will be of little service in any good work. Many of them were the off scouring of the people at first. Now these men have tasted the idleness, the intemperance, the debauchery of a camp—tasted of its riot, tasted of its blood! They will come home before long, hirelings of murder; what will their influence be as fathers, husbands? The nation taught them to fight and plunder the Mexicans for the nation’s sake; the Governor of Massachusetts called on them in the name of “Patriotism” and “Humanity” to enlist for that work: but if, with no justice on our side, it is humane and patriotic to fight and plunder the Mexicans on the nation’s account, why not for the soldier to fight and plunder an American on his own account? Aye, why not?—that is a distinction too nice for common minds; by far too nice for mine.

See the effect on the nation. We have just plundered Mexico; taken a piece of her territory larger than the thirteen states which fought the Revolution, a hundred times as large as Massachusetts; we have burnt her cities, have butchered her men, have been victorious in every contest. The Mexicans were as unprotected women, we, armed men. See how the lust of conquest will increase. Soon it will be the ambition of the next president to extend the “area of freedom” a little further South; the lust of conquest will increase. Soon we must have Yucatan, Central America, all of Mexico, Cuba, Porto Rico, Haiti, Jamaica—all the islands of the Gulf. Many men would gladly, I doubt not, extend the area of freedom so as to include the free blacks of those islands. We have long looked with jealous eyes on West Indian emancipation—hoping the scheme would not succeed. How pleasant it would be to re-establish slavery in Haiti and Jamaica—in all the islands whence the Gold of England or the Ideas of France have driven it out. If the South wants this, would the North object? The possession of the West Indies would bring much money to New England, and what is the value of Freedom compared to coffee and sugar—and cotton?

I must say one word of the effect this war has had on political parties. By the parties I mean the leaders thereof, the men that control the parties. The effect on the Democratic party, on the majority of Congress, on the most prominent men of the nation, has been mentioned before. It has shut their eyes to truth and justice, it has filled their mouths with injustice and falsehood. It has made one man “available” for the Presidency who was only known before as a sagacious general, that fought against the Indians in Florida, and acquired a certain reputation by the use of Bloodhounds, a reputation which was rather unenviable even in America. The battles in northern Mexico made him conspicuous, and now he is seized on as an engine to thrust one corrupt party out of power and to lift in another party, I will not say less corrupt,–I wish I could,–it were difficult to think it more so. This latter party has been conspicuous for its opposition to a military man as ruler of a free people; recently it has been smitten with sudden admiration for military men, and military success, and tells the people, without a blush, that a military man fresh from a fight which he disapproved of is most likely to restore peace, because most familiar with the evils of war! In Massachusetts the prevalent political party, as such, for some years seems to have had no moral principle; however, it had a prejudice in favor of decency—now it has thrown that overboard, and has not even its respectability left. Where are its “Resolutions”? Some men knew what they were worth long ago; now all men can see what they are worth.

The cost of the war in money and men I have tried to calculate, but the effect on the morals of the people—on the Press, the Pulpit, and the parties—and through them on the rising generation, it is impossible to tell. I have only faintly sketched the outline of that. The effect of the war on Mexico herself—we can dimly see in the distance. The government of the United States has willfully, wantonly broken the peace of the continent. The Revolutionary war was unavoidable, but for this invasion there is no excuse. That God, whose providence watches over the falling nation as the falling sparrow, and whose comprehensive plans are now advanced by the righteousness and now by the wrath of man,–He who stilleth the waves of the sea and the tumult of the people, will turn all this wickedness to account in the history of man. If that I have no doubt. But that is no excuse for American crime. A greater good lay within our grasp, and we spurned it away.

Well, before long the soldiers will come back—such as shall ever come—the regulars and volunteers, the husbands of the women whom your charity fed last winter, housed and clad and warmed. They will come back. Come, New England, with your posterity of states, go forth to meet your sons returning all “covered with imperishable honors.” Come, men, to meet your fathers, brothers. Come, women, to your hisbands and your lovers; come. But what! Is that the body of men who a year or two ago went forth, so full of valor and of rum? Are these rags the imperishable honors that cover them? Here is not half the whole. Where is the wealth they hoped from the spoil of churches? But the men—“Where is my husband?” says one; “and my son?” says another. “They fell at Jalapa, one, and one at Cerro Gordo, but they fell covered with imperishable honor, for ‘twas a famous victory.” “Where is my lover?” screams a woman whom anguish makes respectable spite of her filth and ignorance;–“and our father, where is he?” scream a troop of half-starved children, staring through their dirt and rags. “One died of the vomit at Vera Cruz. Your father, little ones, we scourged the naked man to death at Mixcoac.”

But that troop that is left—who are in the arms of wife and child—they are the best sermon against war; this has lost an arm and that a leg; half are maimed in battle, or sickened with the fever; all polluted with the drunkenness, idleness, debauchery, lust, and murder of a camp. Strip off this man’s coat, and count the stripes welted into his flesh—stripes laid on by demagogues that love the people, the D E A R people. See how affectionately the war-makers branded the dear soldiers with a letter D, with a red hot iron, in the cheek. The flesh will quiver as the irons burn—no matter. It is only for love of the people that all this is done, and we are all of us covered with imperishable honors. D stands for Deserter,–aye, and for Demagogue—yes, and for Demon too. Many a man shall come home with but half of himself—half his body, less than half his soul.

“Alas the mother, that his bare,

If she could stand in presence there,

In that wan cheek and wasted air,

She would not know her child.”

“Better,” you say, “for us better, and for themselves better by far, if they had left that remnant of a body in the common ditch where the soldier finds his bed of honor,–better have fed therewith the vultures of a foreign soil, than thus come back.” No, better come back, and live here, mutilated, scourged, branded, a cripple, a pauper, a drunkard, and a felon,–better darken the windows of the jail and blot the gallows with unusual shame—to teach us all that such is war, and such the results of every “famous victory,” such the imperishable honors that it brings, and how the war-makers love the men they rule! Oh Christian America! Oh New England, child of the Puritans! Cradled in the wilderness, thy swaddling garments stained with martyrs’ blood, hearing in thy youth the war-whoop of the savage and thy mother’s sweet and soul-composing hymn:–

“Hush, my child, lie still and slumber,

Holy angels guard thy bed;

Heavenly blessings, without number,

Rest upon thine infant head:”

Come, New England, take the old-banners of thy conquering host—the standards borne at Monterey, Palo Alto, Buena Vista, Vera Cruz, the “glorious stripes and stars” that waved over the walls of Churubusco, Contreras, Puebla, Mexico herself,–flags blackened with battle and stiffened with blood, pierced by the lances and torn with the shot—bring them into thy churches, hang them up over altar and pulpit, and let little children, clad in white raiment and crowned with flowers, come and chant their lessons for the day:

“Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.”

Then let the Priest say—“Righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach unto any people. Blessed is the Lord my strength. Which teacheth my hands to war, and my fingers to fight. Happy is that people that is in such a case. Yea, happy is that people whose God is the Lord, and Jesus Christ their Saviour.”

Then let the soldiers who lost their limbs and the women who lost their husbands and their lovers in the strife, and the men—wiser than the children of light—who made money out of the war; let all the people—like people and like priest—say “Amen.”

But suppose these men were to come back to Boston on a day when, in civil style, as having never sinned yourself, and never left a man in ignorance and want to be goaded into crime, you were about to hang three men—one for murder, one for robbery with the armed hand, and one for burning down a house. Suppose, after the fashion of “The good old times,” you were to hang those men in public, and lead them in long procession through your streets, and while you were welcoming these returned soldiers and taking their officers to feast in “the Cradle of Liberty,” they should meet the sheriff’s procession escorting those culprits to the gallows. Suppose the warriors should ask, “Why, what is that?” What would you say? Why, this. “These men—they broke the law of God, by violence, by fire and blood, and we shall hang them for the public good, and especially for the example, to teach the ignorant, the low, and the weak.” Suppose these three felons—the halters round their neck—should ask also, “Why, what is that?” You would say, “They are the soldiers just come back from war. For two long years they have been hard at work, burning cities, plundering a nation, and butchering whole armies of men. Sometimes they killed a thousand in a day. By their help, the nation has stolen seven hundred thousand square miles of land!” Suppose the culprits ask, “Where will you hang so many?” “Hand them!” is the answer—we shall only hang you. It is written in our Bible that one murder makes a villain, millions a hero. We shall feast these men full of bread and wine; shall take their leader, a rough man and a ready—one who by perpetual robbery holds a hundred slaves and more—and make him a King over all the land. But as you only burnt, robbed, and murdered on so small a scale, and without the command of the President or the Congress, we shall hang you by the neck. Our Governor ordered these men to go and burn and rob and kill, now he orders you to be hanged, and you must not ask any more questions, for the hour is already come.”

To make the whole more perfect—suppose a native of Loo-Choo, converted to Christianity by your missionaries in his native land, had come hither to have “the way of God” “expounded unto him more perfectly,” that he might see how these Christians love one another. Suppose he should be witness to a scene like this!

To men who know the facts of war, the wickedness of this particular invasion and its wide-extending consequences, I fear that my words will seem poor and cold and tame. I have purposely mastered my emotion, telling only my thought. I have uttered no denunciation against the men who caused this destruction of treasure, this massacre of men, this awful degradation of the moral sense. The respectable men of Boston—“the men of property and standing” all over the State, the men that commonly control the politics of New England—tell you that they dislike the war. But they re-elect the men that made it. Has a single man in all New England lost his seat in any office because he favored the war? Not a man. Have you ever known a Northern Merchant who would not let his ship for the war, because the war was wicked and he a Christian? Have you ever known a Northern Manufacturer who would not sell a kernel of powder, nor a cannon-ball, nor a coat, nor a shirt for the war? Have you ever known a Capitalist—a man who lives by letting money—refuse to lend money for the war because the war was wicked? Not a Merchant, not a Manufacturer, not a Capitalist. A little money—it can buy up whole hosts of men. Virginia sells her negroes,–what does New England sell? There was once a man in Boston, a rich man too, not a very great man—only a good one who loved his country—and there was another poor man here, in the times that tried men’s souls,–but there was not money enough in all England, not enough promise of honors, to make Hancock and Adams false to their sense of right. Is our soil degenerate, and have we lost the race of noble men?

No, I have not denounced the men who directly made the war, or indirectly egged he people on. Pardon me, thou prostrate Mexico, robbed of more than half thy soil, that America may have more slaves; thy cities burned, thy children slain, the streets of thy capital trodden by the alien foot, but still smoking with thy children’s blood,–pardon me if I seem to have forgotten thee. And you, ye butchered Americans, slain by the vomito, the gallows, and the sword; you, ye maimed and mutilated men, who shall never again join hands in prayer, never kneel to God once more upon the limbs he made you; you, ye widows, orphans of these butchered men—far off in that ore sunny south, here in our own fair land—pardon me that I seem to forget your wrongs. And thou, my country, my own, my loved, my native land, thou child of Great Ideas and mother of many a noble son—dishonored now, thy treasure wasted, thy children killed or else made murders, thy peaceful glory gone, thy government made to pimp and pander for lust of crime,–forgive me that I seem over gentle to the men who did and do the damning deed that wastes thy treasure, spills thy blood, and stains thine honor’s sacred fold. And you, ye sons of men everywhere, thou child of God, mankind, whose latest, fairest hope is planted here in this new world,–forgive me if I seem gentle to thy enemies, and to forget the crime that so dishonors man, and makes this ground a slaughter-yard of men—slain, too, in furtherance of the basest wish. I have no words to tell the pity that I feel for them that did the deed. I only say, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do!”

A sectarian church could censure a general for holding his candle in a Catholic cathedral—‘twas “a candle to the Pope”—yet never dared to blame the war; while we loaded a ship-of-war with corn and sent off the Macedonian to Cork, freighted by private bounty to feed the starving Irishman, the State sent her ships to Vera Cruz, in a cause most unholy, to bombard, to smite, and to kill. Father! Forgive the State, forgive the Church. ‘Twas an ignorant State, ‘twas a silent Church—a poor, dumb dog, that dared not bark at the wolf who prowls about the fold, but only at the lamb.

Yet ye leaders of the land, know this,–that the blood of thirty thousand men cries out of the ground against you. Be it your folly or your crime, still cries the voice—WHERE IS THY BROTHER? That thirty thousand—in the name of Humanity I ask, where are they? In the name of Justice I answer, YOU SLEW THEM.