The Battle of Baltimore was fought in September 1814–during the War of 1812 as a part of the British’s attempt to reclaim America. Having just burned the U. S. Capitol and the White House, the British boldly advanced on Baltimore and Fort McHenry. The Americans there defended against two land attacks, only to have the British begin bombarding Fort McHenry from their ships at sea.

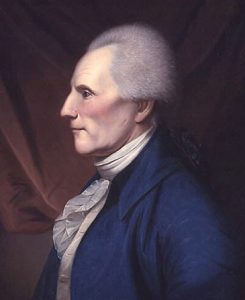

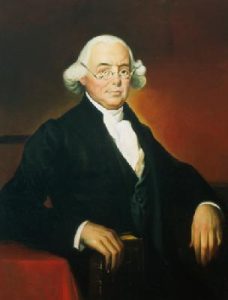

Fort McHenry had been named for Constitution signer James McHenry, who was Secretary of War under both President George Washington and President John Adams. [1] Interestingly, McHenry’s own son John fought as a volunteer in that battle [2] — a battle best known for birthing America’s national anthem: “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Fort McHenry had been named for Constitution signer James McHenry, who was Secretary of War under both President George Washington and President John Adams. [1] Interestingly, McHenry’s own son John fought as a volunteer in that battle [2] — a battle best known for birthing America’s national anthem: “The Star Spangled Banner.”

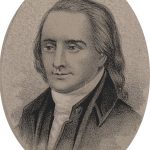

Before the battle began, Francis Scott Key, local attorney on a mission from President James Madison, boarded a British ship to secure the release of a prisoner taken by the British. Although successful in his mission, the British held Key aboard the ship until the attack was finished.

Anxiously watching as the fleet fired round after round into the fort, darkness fell, but the fierce bombardment continued throughout the night. When the guns finally fell silent, Key worried that the Fort had fallen. But when the sun arose, he spied the American flag still flying over the fort, unconquered!

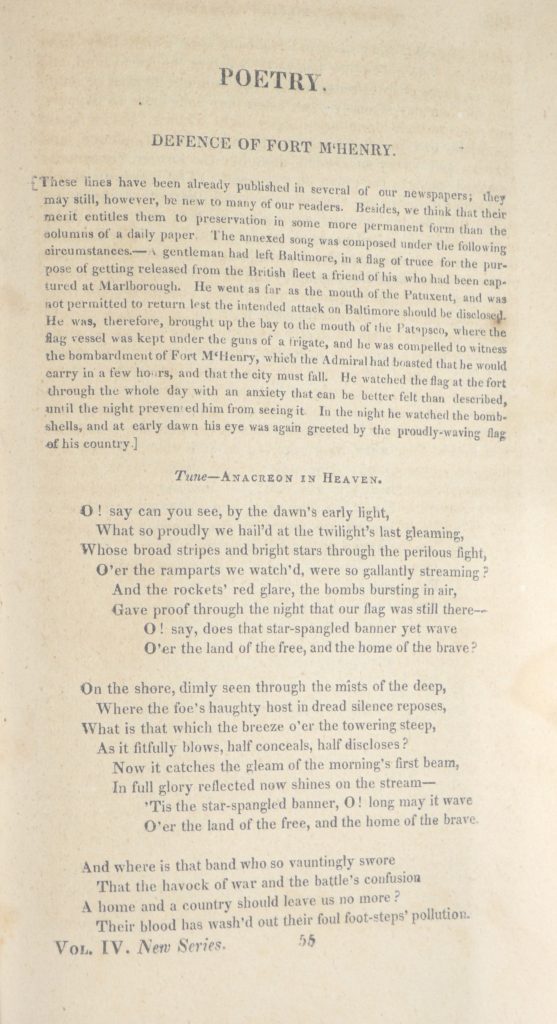

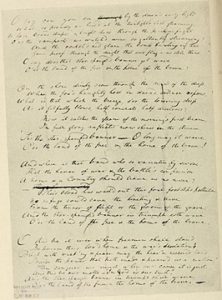

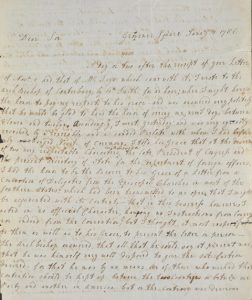

Still aboard the ship, on the back of an envelope he began jotting down lines recording what he saw and felt. Later that day after arriving ashore, he finished the poem. Originally called “The Defense of Ft. McHenry,” it would eventually become the national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It was printed shortly after the battle in the 1814 Analectic Magazine (shown below from our WallBuilders Library).

Francis Scott Key, a committed Christian, contemplated giving up his profession to become a minister, [3] but decided to continue in law. He befriended John Randolph (a U.S. Congressman who openly expressed a preference for the Muslim faith and an opposition to Christianity) and persuaded him to embrace Christianity, after which Randolph became a strong advocate for his new-found faith. [4] Key wrote Randolph:

[M]ay I always hear that you are following the guidance of that blessed Spirit that will ‘lead you into all truth,’ leaning on that Almighty arm that has been extended to deliver you, trusting only in the only Savior, and ‘going on’ in your way to Him ‘rejoicing.’ [5]

Key served on the board of the American Bible Society and also the American School Union.

We have a short downloadable video on the origin of the Star Spangled Banner and its declaration of reliance on God. Play this for your friends, or at your church, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of our national anthem. We also have a wonderful biography of this great Christian statesman.

Endnotes

1 Robert K. Wright, Jr. and Morris J. MacGregor, Jr., Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution, “James McHenry: Maryland,” (Center of Military History United States Army: Washington, D.C., 1987), 106-108; “James McHenry,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, accessed March 20, 2025.

2 Bernard C. Steiner, The Life and Correspondence of James McHenry (Cleveland: Burrows Brothers Co., 1907), 610.

3 “Francis Scott Key,” Fort McHenry, September 3, 2014.

4 Hugh A. Garland, The Life of John Randolph of Roanoke (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1850), II:87-88, from a letter to John Randolph, May, 22, 1816; 99-100, from a letter to Francis Scott Key, September 7, 1818; 100-103, from a letter to Dr. Brockenbrough, September 25, 1818; 103-104, from a letter to John Randolph; 106-107, Key’s reply to Randolph’s letter of May 3, 1819; 107-108, from a letter to Francis Scott Key, August 18, 1819;109, from a letter to Francis Scott Key, August 22, 1819; 373-374.

5 Garland, Life of John Randolph (1850), II:104, from Francis Scott Key to John Randolph.

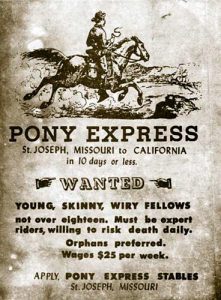

William H. Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell founded the

William H. Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell founded the  The recruitment

The recruitment  Among the many items WallBuilders owns is one of these very rare Pony Express

Among the many items WallBuilders owns is one of these very rare Pony Express

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city after an eleven month occupation at the start of the American Revolution.

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city after an eleven month occupation at the start of the American Revolution.

At that time, attorney

At that time, attorney

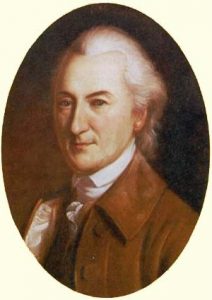

Richard Henry Lee was part of a large family that was something of a political dynasty for the better part of two centuries. His father, Thomas, served as

Richard Henry Lee was part of a large family that was something of a political dynasty for the better part of two centuries. His father, Thomas, served as  After the American Revolution ended, and while serving as President of the Continental Congress in 1784-1785, Richard

After the American Revolution ended, and while serving as President of the Continental Congress in 1784-1785, Richard

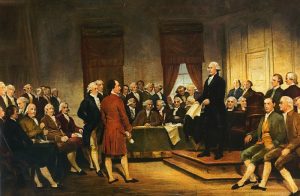

Wilson served as a Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress, where he voted for and signed the Declaration of Independence. He later was a member of the Constitutional Convention, where he signed the Constitution.

Wilson served as a Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress, where he voted for and signed the Declaration of Independence. He later was a member of the Constitutional Convention, where he signed the Constitution.

America’s first attempt at a national governing document was in 1777 with the Articles of Confederation.

America’s first attempt at a national governing document was in 1777 with the Articles of Confederation. James Madison agreed:

James Madison agreed: Many delegates involved with writing the Constitution were trained in theology or ministry,

Many delegates involved with writing the Constitution were trained in theology or ministry,