Founders & Democracy

We have grown accustomed to hearing that we are a democracy; such was never the intent. The form of government entrusted to us by our Founders was a republic, not a democracy. 1 Our Founders had an opportunity to establish a democracy in America and chose not to. In fact, the Founders made clear that we were not, and were never to become, a democracy:

[D]emocracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have, in general, been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. 2 James Madison

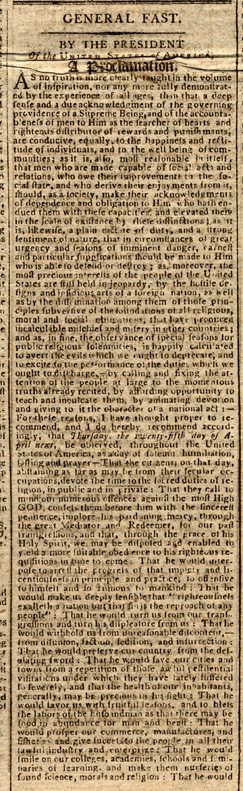

Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. 3 John Adams

A democracy is a volcano which conceals the fiery materials of its own destruction. These will produce an eruption and carry desolation in their way. 4 The known propensity of a democracy is to licentiousness [excessive license] which the ambitious call, and ignorant believe to be liberty. 5 Fisher Ames, Author of the House Language for the First Amendment

We have seen the tumult of democracy terminate . . . as [it has] everywhere terminated, in despotism. . . . Democracy! savage and wild. Thou who wouldst bring down the virtuous and wise to thy level of folly and guilt. 6 Gouverneur Morris, Signer and Penman of the Constitution

[T]he experience of all former ages had shown that of all human governments, democracy was the most unstable, fluctuating and short-lived. 7 John Quincy Adams

A simple democracy . . . is one of the greatest of evils. 8 Benjamin Rush, Signer of the Declaration

In democracy . . . there are commonly tumults and disorders. . . . Therefore a pure democracy is generally a very bad government. It is often the most tyrannical government on earth. 9 Noah Webster

Pure democracy cannot subsist long nor be carried far into the departments of state, it is very subject to caprice and the madness of popular rage. 10 John Witherspoon, Signer of the Declaration

It may generally be remarked that the more a government resembles a pure democracy the more they abound with disorder and confusion. 11 Zephaniah Swift, Author of America’s First Legal Text

Many Americans today seem to be unable to define the difference between the two, but there is a difference, a big difference. That difference rests in the source of authority.

Democracy & Republic Definitions

A pure democracy operates by direct majority vote of the people. When an issue is to be decided, the entire population votes on it; the majority wins and rules.

A republic differs in that the general population elects representatives who then pass laws to govern the nation.

A democracy is the rule by majority feeling (what the Founders described as a “mobocracy” 12). A republic is rule by law.

If the source of law for a democracy is the popular feeling of the people, then what is the source of law for the American republic? According to Founder Noah Webster:

[O]ur citizens should early understand that the genuine source of correct republican principles is the Bible, particularly the New Testament, or the Christian religion. 13

The American Republic

The transcendent values of Biblical natural law were the foundation of the American republic. Consider the stability this provides: in our republic, murder will always be a crime, for it is always a crime according to the Word of God. however, in a democracy, if majority of the people decide that murder is no longer a crime, murder will no longer be a crime.

America’s immutable principles of right and wrong were not based on the rapidly fluctuating feelings and emotions of the people but rather on what Montesquieu identified as the “principles that do not change.” 14

Benjamin Rush similarly observed:

[W]here there is no law, there is no liberty; and nothing deserves the name of law but that which is certain and universal in its operation upon all the members of the community. 15

In the American republic, the “principles which did not change” and which were “certain and universal in their operation upon all the members of the community” were the principles of Biblical natural law. In fact, so firmly were these principles ensconced in the American republic that early law books taught that government was free to set its own policy only if God had not ruled in an area. For example, Blackstone’s Commentaries explained:

To instance in the case of murder: this is expressly forbidden by the Divine. . . . If any human law should allow or enjoin us to commit it we are bound to transgress that human law. . . . But, with regard to matters that are . . . not commanded or forbidden by those superior laws such, for instance, as exporting of wool into foreign countries; here the . . . legislature has scope and opportunity to interpose. 16

The Founders echoed that theme:

All [laws], however, may be arranged in two different classes. 1) Divine. 2) Human. . . . But it should always be remembered that this law, natural or revealed, made for men or for nations, flows from the same Divine source: it is the law of God. . . . Human law must rest its authority ultimately upon the authority of that law which is Divine. 17 James Wilson, Signer of the Constitution; U. S. Supreme Court Justice

[T]he law . . . dictated by God Himself is, of course, superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity if contrary to this. 18Alexander Hamilton, Signer of the Constitution

[T]he . . . law established by the Creator . . . extends over the whole globe, is everywhere and at all times binding upon mankind. . . . [This] is the law of God by which he makes his way known to man and is paramount to all human control. 19 Rufus King, Signer of the Constitution

Conclusion

The Founders understood that Biblical values formed the basis of the republic and that the republic would be destroyed if the people’s knowledge of those values should ever be lost.

A republic is the highest form of government devised by man, but it also requires the greatest amount of human care and maintenance. If neglected, it can deteriorate into a variety of lesser forms, including a democracy (a government conducted by popular feeling); anarchy (a system in which each person determines his own rules and standards); oligarchy (a government run by a small council or a group of elite individuals): or dictatorship (a government run by a single individual). As John Adams explained:

[D]emocracy will soon degenerate into an anarchy; such an anarchy that every man will do what is right in his own eyes and no man’s life or property or reputation or liberty will be secure, and every one of these will soon mould itself into a system of subordination of all the moral virtues and intellectual abilities, all the powers of wealth, beauty, wit, and science, to the wanton pleasures, the capricious will, and the execrable [abominable] cruelty of one or a very few. 20

Understanding the foundation of the American republic is a vital key toward protecting it.

Endnotes

1 An example of this is demonstrated in the anecdote where, having concluded their work on the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin walked outside and seated himself on a public bench. A woman approached him and inquired, “Well, Dr. Franklin, what have you done for us?” Franklin quickly responded, “My dear lady, we have given to you a republic–if you can keep it.” Taken from “America’s Bill of Rights at 200 Years,” by former Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, printed in Presidential

Studies Quarterly (Summer 1991), XXI:3:457. This anecdote appears in numerous other works as well.

2 Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, James Madison, The Federalist on the New Constitution (Philadelphia: Benjamin Warner, 1818), 53, #10, James Madison.

3 John Adams to John Taylor, April 15, 1814, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), VI:484.

4 Fisher Ames, Speech on Biennial Elections, delivered January, 1788, Works of Fisher Ames (Boston: T. B. Wait & Co., 1809), 24.

5 Ames, “The Dangers of American Liberty,” February 1805, Works (1809), 384.

6 Gouverneur Morris, An Oration Delivered on Wednesday, June 29, 1814, at the Request of a Number of Citizens of New-York, in Celebration of the Recent Deliverance of Europe from the Yoke of Military Despotism (New York: Van Winkle and Wiley, 1814), 10, 22.

7 John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution. A Discourse Delivered at the Request of the New York Historical Society, in the City of New York on Tuesday, the 30th of April 1839; Being the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Inauguration of George Washington as President of the United States, on Thursday, the 30th of April, 1789 (New York: Samuel Colman, 1839), 53.

8 Benjamin Rush to John Adams, July 21, 1789, The Letters of Benjamin Rush, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Princeton: Princeton University Press for the American Philosophical Society, 1951), I:523.

9 Noah Webster, The American Spelling Book: Containing an Easy Standard of Pronunciation: Being the First Part of a Grammatical Institute of the English Language, To Which is Added, an Appendix, Containing a Moral Catechism and a Federal Catechism (Boston: Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews, 1801), 103-104.

10 John Witherspoon, Lecture 12 on Civil Society, The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), VII:101.

11 Zephaniah Swift, A System of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham: John Byrne, 1795), I:19.

12 See, for example, Benjamin Rush to John Adams, January 22, 1789, Letters, ed. Butterfield (1951), I:498.

13 Noah Webster, History of the United States (New Haven: Durrie & Peck, 1832), 6.

14 George Bancroft, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1859), V:24; Baron Charles Secondat de Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws (Philadelphia: Isaiah Thomas, 1802), I:17-23, and ad passim.

15 Rush to David Ramsay, March or April 1788, Letters, ed. Butterfield (1951), I:454.

16 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Philadelphia: Robert Bell, 1771), I:42-43.

17 James Wilson, “Of the General Principles of Law and Obligation,” The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, ed. Bird Wilson (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), I:103-105.

18 Alexander Hamilton, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), I:87, February 23, 1775, quoting Blackstone, Commentaries (1771), I:41.

19 Rufus King to C. Gore, February 17, 1820, The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King, ed. Charles R. King (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), VI:276.

20 John Adams, The Papers of John Adams, ed. Robert J. Taylor (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1977), I:83, from “An Essay on Man’s Lust for Power, with the Author’s Comment in 1807,” written on August 29, 1763, but first published by John Adams in 1807.

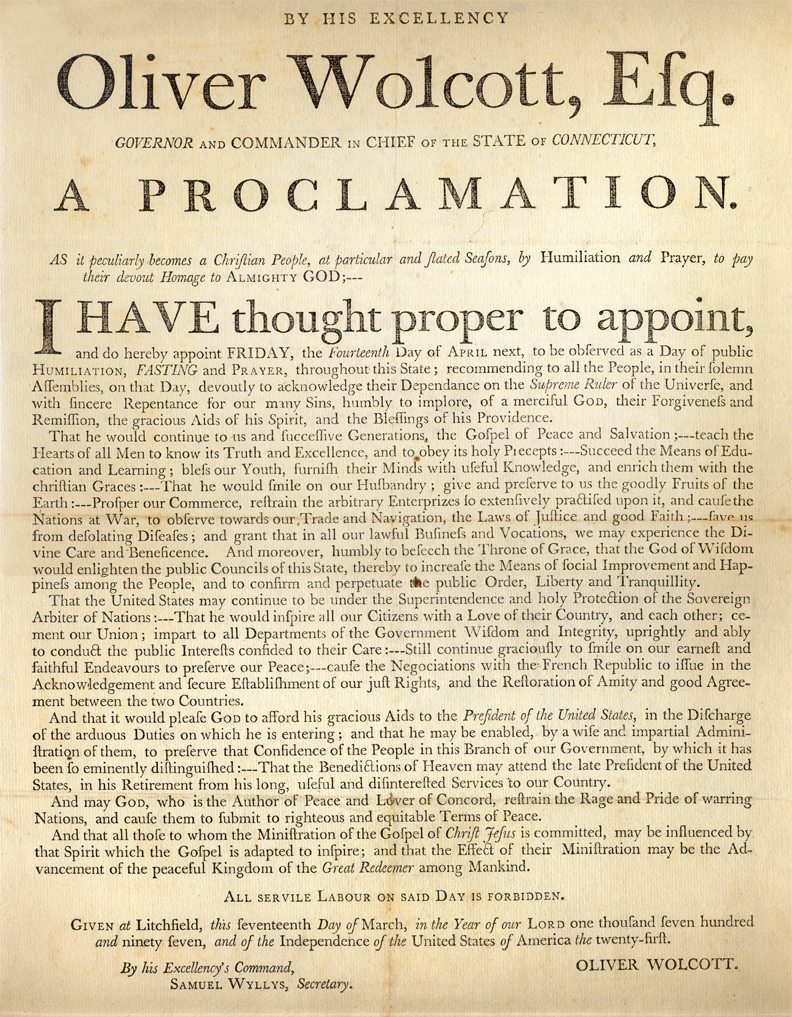

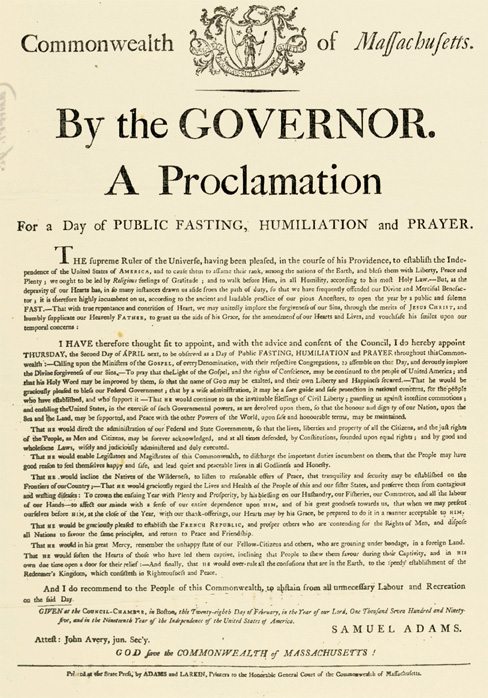

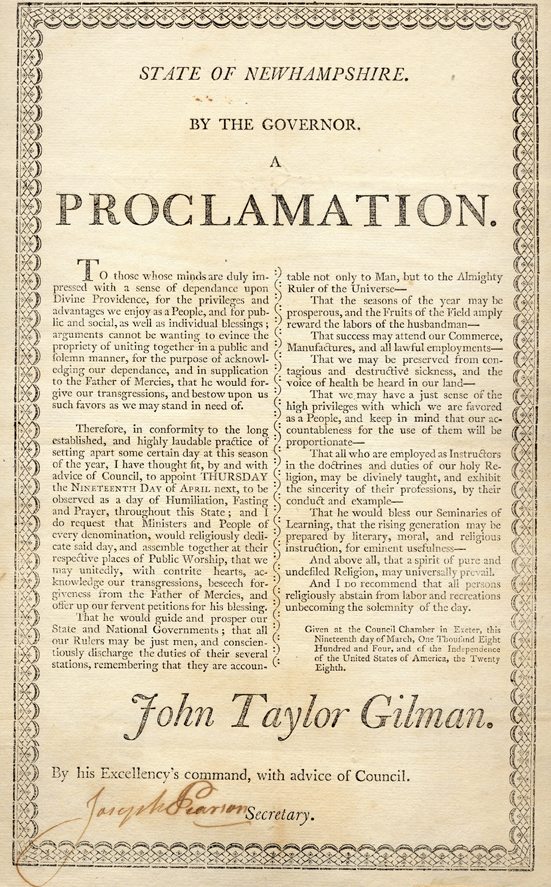

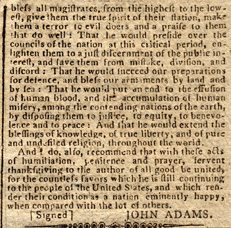

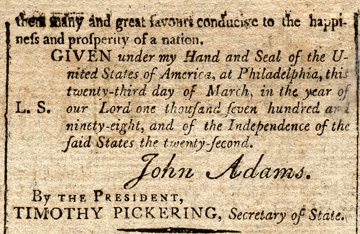

And finally I recommend, that on the said day; the duties of humiliation and prayer be accompanied by fervent Thanksgiving to the bestower of every good gift, not only for having hitherto protected and preserved the people of these United States in the independent enjoyment of their religious and civil freedom, but also for having prospered them in a wonderful progress of population, and for conferring on them many and great favours conducive to the happiness and prosperity of a nation.

And finally I recommend, that on the said day; the duties of humiliation and prayer be accompanied by fervent Thanksgiving to the bestower of every good gift, not only for having hitherto protected and preserved the people of these United States in the independent enjoyment of their religious and civil freedom, but also for having prospered them in a wonderful progress of population, and for conferring on them many and great favours conducive to the happiness and prosperity of a nation.

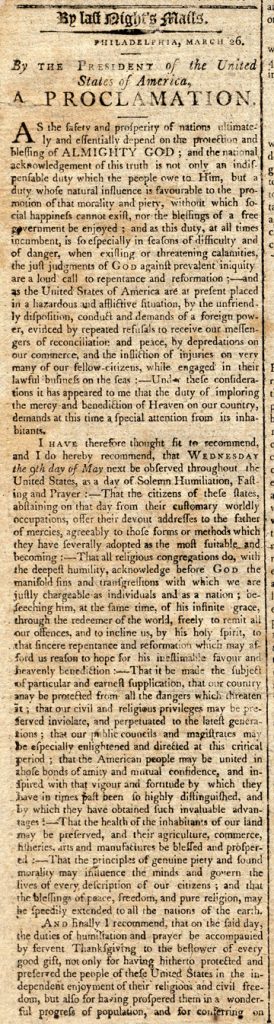

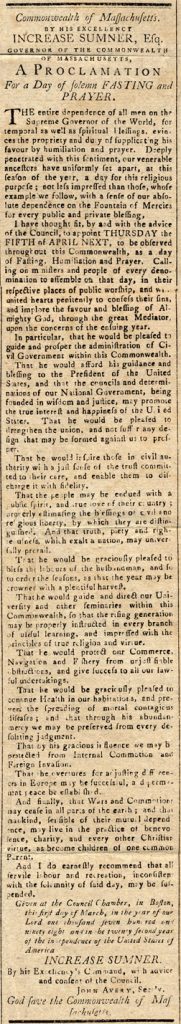

The entire dependence of all men on the Supreme Governor of the World, for temporal as well as spiritual blessings, evinces the propriety and duty of supplicating His favor by humiliation and prayer. Deeply penetrated with this sentiment, our venerable ancestors have uniformly set apart, at this season of the year, a day for this religious purpose; not less impressed than those, whose example we follow, with a sense of our absolute dependence on the Fountain of Mercies for every public and private blessing,

The entire dependence of all men on the Supreme Governor of the World, for temporal as well as spiritual blessings, evinces the propriety and duty of supplicating His favor by humiliation and prayer. Deeply penetrated with this sentiment, our venerable ancestors have uniformly set apart, at this season of the year, a day for this religious purpose; not less impressed than those, whose example we follow, with a sense of our absolute dependence on the Fountain of Mercies for every public and private blessing,