Byron Sunderland was born in Shoreham on November 22, 1819. He served 45 years as Pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Washington D.C. Sunderland spoke privately about Christian philosophy with Lincoln. He served as Chaplain of the U.S. Senate, and presided over the wedding of President Grover Cleveland at the White House. Notably, he preached in favor of abolition, at a time, and in a place, where it was dangerous to do so.

SERMON

ON THEPUBLIC WORSHIP OF GOD,

DELIVERED IN THEHALL OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

SUNDAY, JANUARY 31ST, 1864AND REPEATED, BY REQUEST, IN UNION HALL, NO. 481 NINTH STREET,

MONDAY, FEBRUARY 8TH, 1864,BY: REV. B. SUNDERLAND, D.D.

Pastor of First Presbyterian Church, and Chaplain U.S. Senate for Thirty-Eighth Congress.

PUBLISHED BY REQUEST.

WASHINGTON, D.C.

CHRONICLE PRINT.

1864.

Washington, D.C. Feb. 4, 1864.

REV’D BYRON SUNDERLAND, D.D.,

Chaplain U. S. Senate:

DEAR SIR: Realizing the great value of the truths enunciated in the sermon delivered by you in the House of Representatives of the United States last Sabbath morning, “on the duty of maintaining the public worship of God,” knowing its most gratifying reception by the immense audience convened on that occasion, and feeling that others will be profited by hearing it, we invite you to repeat it at Hall No. 481 Ninth street, at a time agreeable to yourself, and also that you furnish a copy for publication.

With sentiments of high regard, we remain

Yours, very truly,

HENRY A. BREWSTER, New York. WILLIAM BEBB, Ohio.

JUDSON S. BROWN, Massachusetts. HANNIBAL HAMLIN, Maine.

LEONARD S. FARWELL, Wisconsin SCHUYLER COLFAX, Indiana.

THADEUS STEVENS, Pennsylvania. SOLOMON FOOT, Vermont.

AUGUSTIN CHESTER, Illinois D. CLARKE, New Hampshire.

JAMES M. EDMUNDS, Michigan. J. A. BROWN, Rhode Island.

B. B. FRENCH, Washington, D. C. W. C. DODGE, Minnesota.

A. F. WILLIAMS, Connecticut. J. CONNESS, California.

A. M. SCOTT, Iowa. A. CARTER WILDER, Kansas.

N. B. SMITHERS, Delaware. R. G. GREENE, Virginia.

J. D. MERRILL, Missouri. HANISON REED, Florida.

J. W. NESMITH, Oregon. J. D. DOTY, Utah.

J. F. SHARETTS, Maryland. J. CLAY SMITH, Kentucky.

WASHINGTON, D. C., Feb. 5, 1864.

TO MESSRS. BREWSTER, BEBB, BROWN, HAMLIN, FARWELL, and others:

GENTLEMEN: Your note of the 4th inst. Is received, inviting me to repeat the discourse “on the duty of maintaining the public worship of God,” delivered in the House of Representatives January 31, 1864. I cheerfully comply with the request, and designate Monday evening, the 8th inst., as the time.It is with thanksgiving to God that I find such sentiments endorsed by you, as the representatives of the great Christian community throughout the United States. With trembling I think of the stern and fearful time in which we live, and of the stupendous contest for the supremacy of the law and of the perpetuity of the Union in which the nation is engaged.

I feel sure we all desire the triumph of our Government over the rebellion, because we believe it will be a victory for righteousness in the earth.

We must have Jehovah for our Captain by conforming to his requirements, and especially maintaining the public ordinances of his worship.

With sincere regards,

B. SUNDERLAND.

SERMON.

ISAIAH 66:23

“And it shall come to pass that from one new moon to another, and from one Sabbath to another, shall all flesh come to worship before me, says the Lord.”

This is a marvelous prediction. What a day for the world, when the worship of God from month to month, and from week to week, shall be universal!

The worship of God implies the highest acts of which a rational creature is capable. It demands all the powers of body and soul. To conceive and feel all that it implies, and to give suitable outward expression to its thoughts and emotions, by the posture of the body, by the voice, by the various faculties of manifestation, presupposes a character of the noblest culture.

The worship of God may be solitary, as of the individual alone – domestic, as in the family – social, as in the small companies of friends – or public, as in the great and open congregation.

In any case however, to be real it must be spiritual, whatever may be the outward act by which it is expressed – “God is a spirit, and they that worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth.”

And what does this mean but that homage which is due to God as the Father of spirits, and the Supreme King? In acts of worship, we render to God an acknowledgment of his right to rule over us – of the supreme authority of his law, and the righteousness of his kingdom and dominion, in opposition to all other pretended authority whatsoever. For such an act, the whole being of the man is requisite – body, soul, mind, reason, sense, memory, hope, imagination, and the loftiest thoughts of human faith. And as to spirituality, what is it but the life of justice and truth and virtue? Can anything be more spiritual than these? If I pay my honest debt, I hold the essence of that deed is as purely spiritual as the act of the loftiest adoration – both are proper upon occasion, and both befit the highest development of our nature.

Each form of worship of God has its appropriate characteristics, and requires in its observance the outward expression suited to its nature. As I intend, in this discourse to speak chiefly of public worship, I will remark, in passing, that the general usage of the evangelical world has assigned three grand parts to the service of God in the great congregation: prayer – reading and expounding the Holy Scriptures – and praise in singing, with instruments of music; the first two generally conducted by the minister – the last by a choir, or the whole assembly. Each of these parts is held to be of paramount importance, both from their intrinsic fitness and from the long experience of the affections of human nature. Wherever an assembly meets for the public worship of God on the Sabbath, ample provision should be made, if practicable, for the full performance of each of these parts, so that nothing may be wanting to the great object.

In a congregation like this, meeting in a place like this, we have all the material or physical requisites, if properly employed, to make the public worship of God what it ought to be, so far as it depends upon such conditions. If there is a failure, in any degree or in any sense, to make the service all it should be, we must attribute it to ourselves. The Hall itself is sufficient – the attendants here are diligent, courteous and faithful – ministers are provided – the Sabbath day comes round – the word of God lies open before us – the people assemble – and the service begins. That there may be given to public worship its greatest impressiveness, I take leave to mention that some general order should be observed, by all in the congregation, through the different parts of the service. For example, in the reading of the Scriptures and preaching, let all sit with fixed attention upon what is uttered by the minister – not listless, or perhaps asleep – not distracted by idle curiosities – not whispering, or moving about or leaving the assembly, unless by imperative necessity. Custom has stamped all these things as exceedingly vulgar and low-bred, besides being irreverent and insulting to God.

In time of singing, let all stand up, and devoutly join in the hymn of praise by the voice, or in silent meditation. In time of prayer, let all kneel or bow the head forward, attesting by their attitude their sense of the solemnity of the act – and let there be no unnecessary noise or confusion, as is often the case in the time of daily prayer in these chambers – talking, rattling of papers, sitting in the seat, perhaps reading or writing, and in many ways showing that indifference to the act of prayer to God, which is positively shameful. And while on this point, I wish every member of Congress were here today, that I might ask it of these kind gentlemen, such of them as have fallen into this habit – for I rejoice to say that many should be exempted – nay, I would not insinuate that to be a member of Congress is to be prima facie an unchristian man – every man innocent till proved guilty, is the maxim of law to which they, with us, are entitled; and indeed I know some among them to be as noble Christian gentlemen as are to be found in the land – and far, far be it from me to inveigh against men whose lives illustrate the clear virtues and sublime sympathies of our divine religion; who rejoice when it flourishes, and lament when it declines, and who would go to every length of rational sacrifice to promote its extension in the earth – no, not such do I intend – but such rather as profess no such adherence to its cause, and certainly exhibit none to be spoken of – but that I might ask it of them to reform in this particular.

I allude to this subject, not in a spirit of bitterness or personal complaint at all; for I have this to say, that in all my personal intercourse with members of Congress, and with the officers and employees of the Capitol, I have never received anything but kindness and respect, and I should be sorry to have aggrieved any of them, by alluding to these things now – but I do feel a solicitude for the honor of God, and that men should pay that homage to Him which is due to the Father of us all. It is true that many times members are absent from the daily prayers = for which I have heard various reasons alleged – some detained by necessary business – some by providential dispensations – some from want of inclination toward this duty – and some from a positive dislike of the sentiments these gentlemen from this public Sabbath service, many, it is true, worshipping in the churches of the city, but the majority, I fear elsewhere, leaving the assembly here to be largely made up, from week to week, of strangers from all parts of the land, and of the great sojourning public who have no other stated place of worship.

It naturally follows from these very circumstances, that there is no certain reliance to be placed upon any one or any number of persons, for that most important and yet most difficult part of public worship, the praise of God in the singing of sacred hymns. All that can be expected is the voluntary service of those who may be disposed to aid in the singing for the time being, upon a mere voluntary impulse. Congress manifesting so great an indifference to the whole matter, not only by the absence of the greater portion of the members, but also by the decided opposition of the majority to making any provision for such services, it must continue to be a matter of regret that the ordinary resort in such cases to voluntary contributions is not practicable, and consequently if divine service is held here on the Sabbath, it must be subject to the inconvenience, the deficiency and the depression, which I have here pointed out.

It is true, a man may say, what right have you to lecture me on this or any other subject? I reply, by the right of free speech, which God has given me – and when I have given my lecture, in respectful terms, there my responsibility ends, and his begins. If Congress may not choose to receive what they regard as a chaplain’s lecture, that is their business, not mine. This rule applies universally. If you read a lecture to me, I cannot deny you the right – but my own judgment must decide whether it is of any value, and whether or not I will heed it; and I act in this, under a responsibility for which I am accountable, and one day must account to the Judge of all. So I am the more earnest to develop the whole matter before us, as far as it lies in my power.

Now I undertake to say that there is an erroneous and most vicious public sentiment abroad, not only here among the public functionaries of the Government, but everywhere throughout the country, upon the whole question of the public worship of God. Does it ever occur to men, that God has required these public ordinances of religion to be observed unto Him, and has foretold the advent of a day when all flesh shall come and worship before Him? Does it ever occur to men to feel that one is just as much bound by these requirements as another? Does it ever occur to them to think, that one man, as a member of the religious community, has just as much to think, that one man, as a member of the religious community, has just as much interest at stake in the maintenance of these ordinances of Heaven as another? And yet this is really so.

I have truly no more interest in the matter than you have; and you have truly no more interest in the matter than that officer of the Government, high or low, who appropriates the Sabbath day of God to pleasure excursions, and forsakes the public worship of the Almighty, that he may pay court to some foreign minister, or find means for his own private and personal recreation. I say I have no more interest in the matter than we all have in common – for if these ordinances of God are wantonly ignored and willfully neglected – if the great light that shines in them shall finally be extinguished, and the darkness and degradation of vice, precursor of destruction, shall succeed to it – and if finally, the whole structure of society, undermined and s=disintegrated, shall tumble into ruin, I shall have no more to lose than my neighbor, in the common catastrophe! What I lose, he will lose – we shall all be alike despoiled.

Now the whole community may be divided in respect to this matter of public worship, into three classes: 1st, those who attend upon it with some just sense of its true nature and importance; 2d, those who go to the sacred assembly from grossly inadequate, if not wholly improper motives; 3d, those who stay away altogether. Of the first class I have nothing to say, but that it is comparatively small – alas! To small, I fear, for the leavening of the whole lump. Of the second class I have this to say, that I wonder at them. I am thankful to my Maker that whatever may have been, or may now be my faults, I never had the disposition or desire to attend public worship for the simple sake of seeing or being seen – of making a display – of ogling the assembly – and in short for any and every purpose, but the single one which is alone pertinent and proper, the devout and reverent waiting upon the Majesty of earth and heaven. I never had any sympathy with that spirit which can sport and trifle in the place and time of prayer, – I never could comprehend that levity which mocks at the most sacred things, and turns the very sanctuary of Jehovah into a theatre of laughter and of jeers. Of the third class I testify, in the name of religion, that they are moral delinquents by habit and inclination, and in their example before the nation and the world, they support the grand foundation principle of a practical atheism, and to this extent they are corrupters of society and the enemies of mankind. I take my stand on the decrees of God’s word, and boldly declare that any man, who habitually neglects the worship of God, is a traitor not only to the high government and law of God, but also to the security and welfare of human society itself.

Said the devout Witherspoon, one of the signers of the Declaration, and one of the noblest spirits of the Revolution, a Christian and a clergyman of those brave and heroic times – “He is the truest friend to American liberty who is the most sincere and active in promoting true and undefiled religion, and who sets himself with the greatest firmness to bear down profanity and immorality of every kind. Whoever is an avowed enemy to God, I scruple not to call him an enemy to his country. It is your duty in this important and critical season to exert yourselves, everyone in his proper sphere, to stem the tide of prevailing vice, to promote the knowledge of God, the observance of his name and worship, and obedience to his laws. Your duty to God, to your country, to your families, and to yourselves, is the same. True religion is nothing else but an inward temper and an outward conduct suited to your state and circumstances, in the Providence, at any time. And as peace with God and conformity to Him add to the sweetness of creature comforts, while we possess them, so in times of difficulty and trial it is the man of piety and inward principle that we may expect to find the uncorrupted patriot, the useful citizen, and the invincible soldier.”

In affixing his name to the Declaration of Independence, this man rose in that illustrious assembly, and gave utterance to these words: “Mr. President, that noble instrument on your table, which insures immortality to its author, should be subscribed this very morning, by every pen in the House. He who will not respond to its accents, and strain every nerve to carry into effect its provisions, is unworthy the name of freeman. Although these grey hairs may descend into the sepulcher, I would infinitely rather they should descend thither by the hand of the executioner than desert at this crisis the sacred cause of my country.” The words ran through the body like electric fire. Every man arose and affixed his name to that immortal document. He spoke then the best and highest word of the nation. He was the mouthpiece of a people standing on the religion of the Bible.

Every nation under heaven has had its religion, and will have to the end of time. Our own nation has never recognized, in form or principle, any system but that of Christianity, the highest outward expression of which is known in the public service of divine worship maintained among us, especially on the Sabbath day. And of all places in the land, none should be more important, none more command the sympathy and awaken the interest of the whole people, than the public worship of God in the Capital of the nation.

The historical facts connected with this subject are fraught with the deepest importance, and are entitled to the most serious consideration. To go no further back than the adoption of the Federal Constitution, and confining ourselves also simply in this statement to the proceedings had in relation to the chaplains of Congress, we call to mind first, the fact that the Constitution of 1789 forbids Congress to make “law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” – and further says, “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification for any office or public trust in the United States.” This secures two things – the freedom of religion, and the equality of religious sects. But it does not dispense with the divine obligations of the public worship of God. So our fathers believed, and so they acted. The first Congress under the Constitution elected two chaplains, and this practice is continued to the present day. The law of 1789, and of 1816, regulating this subject, and fixing an annual salary which has never exceeded $750, was passed in pursuance of the conviction not only of the constitutionality, but of the eminent propriety and religious obligation of the service to which the chaplains of Congress were appointed.

And while speaking of salary for the chaplain service in this country, permit me to notice the contrast presented by the State establishment of the Church of England. The statistics were furnished me by a friend who has thoroughly examined this whole subject. From tables prepared by him, it appears that the tithing system of Great Britain for the support of the Church, opens an abyss absolutely appalling. One single fact illustrates the truth of this assertion. The amount of annual salary paid to some twenty four individuals in the highest orders of the clergy, aggregates nearly $1,000,000 – the highest single salary reaching over $78,000, and the lowest exceeding $20,000! What then must be the cost of the entire ecclesiastical establishment?

Now, in comparison with this, what is done by our Government for the support of Christianity? Until the present war, which has of course increased the expense of the chaplaincy, still however, leaving it as a system very defective, the little that was attempted by the Government of the United States can be reported in few words. I find from a small volume published in 1856, entitled “Government Chaplains,” by Dr. L. D. Johnson, and containing much interesting and curious information, that there were at that date thirty chaplains in the Army, twenty-four in the Navy, and two in Congress, besides a number of post-chaplains and teachers among the Indians. The whole expense annually to the Government of supporting this body of men did not exceed a quarter of a million of dollars. I venture to assert that no nation ever existed on earth that maintained the popular religion at so cheap a rate. Think of it again.

To say nothing of the army or navy, Congress has two chaplains, and gives them each $750 per annum for their services in daily attendance. I do not for one ask an increase. I am not pleading for money so much as for the moral effect of the observance, in Congress, of the public ordinances of Divine worship. But there is no provision of law regulating or even requiring the public Sabbath service in which we are now engaged, and there never has been from the beginning, so far as I am instructed. It seems to stand alone upon custom. It has been the unvarying usage for the chaplains of Congress to hold one public service in the Capitol on the Sabbath. It is evident that Washington, Franklin, Madison, Ellsworth, Sherman and their illustrious compeers, approved of the custom, and that ever since that day, the greatest, the best, and the purest men in the nation have given it countenance and support. Yet there have been times when questions of the propriety of such services have arisen – times when a portion of the people have petitioned Congress for the abolition of the whole system of the chaplaincy, and consequently of the public religious services which chaplains perform – and times when the system of Government chaplains, and of the Christian ministry itself has met, in the Houses of Congress and out of them, a storm of ridicule, contempt and denunciation.

On the 5th of September, 1774 the American Congress was in session. There was a doubt in the minds of many about the propriety of opening the daily deliberations with prayer, the reason assigned being the great diversity of opinion and religious belief. Then rose the venerable puritan, Samuel Adams, with his long white locks hanging over his shoulders, and spoke as follows: “It does not become men professing to be Christians, convened for solemn deliberation in the hour of their extremity, to say there is so wide a difference in their religious belief that they cannot as one man bow the knee in prayer to the Almighty, whose aid they hope to obtain. Independent as I am, and an enemy to all Prelacy as I am known to be, I move that the Rev. Dr. Duche, of the Episcopal church, be invited to address the Throne of grace in prayer.” Dr. Duche complied, and offered prayer, first in the form of his church, and then in extemporaneous supplication, until all hearts were moved, and the whole assembly were bathed in tears. In the Convention which formed the present Constitution, another scene occurred, no less remarkable and impressive, when the venerable Franklin proposed, in words of profound solemnity never to be forgotten, the introduction of prayer to the Father of Light for that wisdom which was then wanting to harmonize the conflicting elements, and establish the conditions of the nation’s welfare.

Many are the thrilling facts in our country’s history which demonstrate the necessity of public religious services, conducted by the Christian ministry, to the well-being of the Government and the highest prosperity of the whole people. And now I remark, by the way, that a volume has recently been issued, entitled “The Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States,” by the Rev. B. F. Morris, which is the only book of the kind in existence, and which I find to be a perfect treasury of the Christianity of the nation, as embodied in its public monuments, and attested by its public men – a book which ought to become the Manual of the people, and find a place in every library, and be in the possession of every man, woman and child in the nation, and the close companion of all, whether in public or private life. I trust that book will be thoroughly studied by the present generation of Americans, for it has all the interest of a romance, with all the solidity of science, and all the sanctity of religion. Go to that book, if you would see what the great and good men of the nation, from the beginning until now, have thought of the propriety and absolute necessity of the services of the Christian ministry, and of the observance of the public worship of God in our national affairs, and in the high places of the country.

I am mainly indebted to it for the impulse which originated this very discourse – for I saw it in manuscript, and have copiously drawn from it, as from a fountain deep and rare, for all the great words I have quoted, or am about to quote from our illustrious ancestors. Need I say that its loyalty is one of its grandest features; that the very heart of a deep, genuine, glorious devotion to God and the Country and the Constitution, throbs through every page of it. It could not be otherwise, for it is the sum of the great Christian monuments of the fathers who under God built up our nation – laid its foundation, and reared its mighty structure. Oh had the degenerate sons of now dishonored sires in the rebellious States heeded these great lessons, instead of those of their false and lying prophets of a more recent time, how great a ruin they might have averted from their heads!

By the expressed conviction and resolute conduct of the great men of the first age of the Republic, the objections of the ignorant, the profane, the unbelieving, against the Christian religion and its devoted ministers were in a measure silenced. But when at length, in after years, the institution of the Sabbath seemed to be peculiarly and openly endangered by the public example of the Government in the universal running of the mails, the Christian mind of the nation became alarmed, and the Christian ministry lifted up a decided protest, and made their voice heard in the halls of Congress upon that question. This awakened a powerful opposition from the lax and dissolute men of every description, and kindled again into open conflagration the smoldering embers of the popular prejudice against the ministers and services of religion. The debates in Congress of that period attest a severe conflict, in which at last however, the friends and advocates of immorality were virtually discomfited, and the cause of Christianity obtained a substantial triumph. Thus the question of religion, especially as connected with the appointment of chaplains to Congress, and the public worship of God in the Capitol, was left undisturbed for a considerable period. Meantime, however, a series of causes were operating to bring on the conflict in a fiercer form of political partisanship and bitter animadversion.

It must be confessed that the scramble for the office of chaplain to Congress, by many applicants, and by some perhaps not the best qualified for its responsibilities and duties, had been a growing evil, and was becoming an open scandal to the country. Besides this, measures had been proposed in Congress affecting the question of slavery, and the repeal of a compact of long standing, which moved the whole nation to its very foundation. It was an occasion when large portions of the Christian ministry felt justified in bearing an open testimony on the question at issue. Earnest and stirring memorials, signed by large bodies of the clergy, were sent to Congress, and this aroused the indignation of Senators and Representatives of the dominant political party, against whose public policy the petitions of the memorialists were directed. Sad is the chapter of the proceedings and debates in regard to the Christian ministry generally, and especially in regard to the election of chaplains, and their services in the 33d Congress. The very election of a chaplain was characterized as “a farce.” Votes were given for a female to be the chaplain of the House. One speaker alludes to the election, as the election of “an humble chaplain.” Another speaker said, “The candidates are multiplying, and those whose names are now before us are getting uneasy.

I am anxious to have the matter settled, so that the rejected applicants may apply for some other office if they do not get this!” An article appeared in one of the daily papers of the city to this effect: “We are altogether opposed to having chaplains to Congress. We hope the last of them have been elected. It is pretty well understood that those paid for prayers are to be made brief – cut off short, in order to avoid boring Congress. Short as they are, they are bores.” In the Senate, the opposition to the action of a portion of the Christian clergy, and especially to the ministers of New England, took a wider scope. Senators held them up as deserving the grave censure of that body – as not knowing what they were talking about – as bringing our holy religion into disrepute – as agitators, transforming the lamb to the tiger and the lion.

Meanwhile, memorials came up from the profane and infidel in various quarters of the land for the total abolishment of the office of chaplain. The reasons set forth for this were that the continuance of the office was in violation of the Constitution – that it imposed unjust taxation – that it was a virtual establishment of the union of church and state – and that it was subversive of the genius and spirit of American institutions. All these points were fully answered in the reports of the Committees of the two Houses of Congress upon that whole subject, during that ever memorable period. The Christian sentiment and deliberate sense of the people and of their representatives again prevailed, and the office of the chaplain and the public worship of God in this Capitol of the nation survived together! But there are objections still, no doubt, lurking in the popular mind and heart, if not openly expressed, against the whole system of the Chaplaincy, and especially against the public worship of God in this high place, which I propose now to consider.

1. It is unconstitutional. The voice and practice of the fathers refute this charge. The Constitution does not forbid the creation of the office of chaplain, with a salary by law of Congress; nor does it forbid the appropriation of money to support a decent observance of the public worship of God in this Capitol. Congress appropriates thousands of dollars in other ways, not half so much calculated, in my opinion, to promote the public welfare and virtue of the people; and they have a right, under the Constitution, if they so choose, not only to employ a chaplain or chaplains to conduct daily prayers, and the services of public worship here on the Sabbath, but also to devote money from the public treasury to provide a choir, to purchase an organ, and to do all other acts and things necessary to the fullest perfection of divine service. It will not do for any man to undertake to convince me that all this is unconstitutional.

It is a scandal on the Constitution – a reproach to the memory of our fathers – an insult to religion, and impiety toward God. The catholic evangelical church of Christ of this day, in all denominations, will not tolerate such a sentiment – such a satire on the great organic law of a free and Christian people. The Constitution is not at war with the law of God in this particular; and if it were conclusively shown to be, I should go for the higher law of God, and go for conforming the Constitution to that higher law. We have had enough of sneering at this higher law of God in the land for the last fifteen years. This is one of the iniquities that has brought at last the thunders of His judgment upon us.

2. But this would be forming and establishing a union of church and state. Not by any means. I am as much opposed to such a union as any man, and would contend as strongly against it. When our fathers, by the Constitution, deprived Congress of the power to establish religion by law, they did not intend to make us an infidel nation, nor our Government an impious and God-forsaken iniquity. They meant not to divorce religion wholly from the existence and life of the Republic, but only to prevent the union of any Church establishment with the State, in such a way as to bind the conscience and burden the coffers of the people with either the creed or the taxes of any ecclesiastical institution. Nobody finds fault with the employment of Government physicians and surgeons, and yet there is just as much reason on this ground for the complaint of a union of Therapeutics with the State.

What is meant by a State church is such as exists in England, where immense sums are appropriated, and large prerogatives exclusively granted to a single church establishment, at the expense of all others, and this in perpetuity. No such policy has existed under our Constitution, and I trust it never may. But it is a very different thing for Congress to provide for the public recognition and worship of God in their own halls, leaving all men free to act upon their conscience as to their attendance upon the same, responsible alone to God, for the manner in which these obligations are discharged.

3. It is no place for religious services. Ah, and whose opinion is this? Jesus Christ instructs us, that the day has gone by, when the worship of God shall be confined to any one locality exclusive of another – when men shall worship the Father neither alone at Jerusalem nor in the mountains of Samaria, but everywhere, where men shall worship Him in the spirit. The temple, the synagogue, the academy, the market-place, the forum, the theatre, the aeropagus, as well as the Christian sanctuary, have all been used for this high purpose. Nay, the deserts and caves, and fastnesses of the mountains, the vast solitudes of nature, the wide forest, the open sea, under the broad sky in the light of day, in the shadow of midnight, the camp, the caravansary, the hospital, the asylum, the cottage, the seminary, the halls of justice, and the very jails and penitentiaries have been made the temples of the public worship of the Almighty. And now will it do to say that here in the high conclave of the nation, there is no place for the pure, spiritual, public worship of the one only living and true God?

It is the thought of the infidel – it is the word of the profane! I am well aware of the opinion of multitudes in this land in regard to the whole subject of Christianity, its ordinances, its laws, its requirements, it ministry, and especially in regard to those who represent it as chaplains, whether here or in the army or the navy. I know they look with contempt upon the whole arrangement. They treat the whole matter as though it were but the cant of superstition, or the bigotry of ignorance. They look upon chaplains as beggars, and upon God as a myth, and upon his worship as a mummery. They think it superbly magnanimous even to tolerate all this. They think and feel and act as if Christianity had no right to be here in the world, and its ministers ought to be apologizing to every man they meet, for the fault of pursuing their profession. But those who have such ideas are not the wise and virtuous of the land. They are the impious and corrupt, the very dregs and refuse of human society. They want no restraint on their lusts and passions.

They would hear no reproof of their vices. They desire full scope for their briberies, their dishonesties, their peculations, their foul and pestilent iniquities. Such men would no doubt be glad to see God himself dethroned, his law abolished, his government destroyed, and every vestige of his authority swept away, in order that they might run unimpeded and unquestioned into every excess of riot. Why, I hear it on every hand, day by day, whispered in our dwellings, at the street corners, and everywhere, that there is an amount of corruption going on among us, through men connected with the Government, in all its branches, political, pecuniary, personal, official, and in every way, enough to sink the nation by the weight of its own enormities. I hear it said on every side, that the same is true socially with the population of the city, in their resorts of amusement and in their dens of infamy. Now if this be so, would it not be the most natural thing in the world for such a multitude to desire the public monuments of religion to be everywhere destroyed, that they may have full license to run their course of unscrupulous and lawless conduct, without molestation and without restraint.

And now I undertake to say to all such that I ask no leave of them to be following my profession as a minister of Christ. I shall never beg of any such the privilege of staying in the world to preach the Gospel, and to join in the public worship of Almighty God. I shall never go creeping and crawling before any man, in my clerical capacity. If I am not treated as I ought to be, I have the instructions of my Great Master how to proceed. I will shake the dust off my feet for a witness against them, and leaving them to settle the account with God in the day of final reckoning, I will go elsewhere, as Providence may guide my way. It is not for any minister of Christ to be whining and puling among his fellow men, as though he were but half a man himself. Someone remarked to me the other day that a member of Congress had said “he thought it a great privilege that we were allowed the use of this chamber for public worship at all” – and I say if that is the sense of the American Congress, I for one will leave them, the moment it is ascertained, to do their own preaching and praying, and to follow out their own devices in their own way.

I will not waste my breath upon any class of men who, in this age and country, feel like that. The man who repudiates the Christian religion, and shows his contempt for all it enjoins, and for all who represent and serve it, does not reflect that it is the parent of all the highest social, intellectual, civil and moral good in the land – that it has fostered into greatness all the resources, industries, prosperities, honors and dignities of the nation – that it has adorned our civilization with its rarest ornaments – that it has given to woman her true place in the scale of life – that it has multiplied all the charities and magnanimities of human nature – and he may well be told, in the sententious language of Dr. Franklin, who on one occasion wrote, with a quiet satire only equaled by the truth of the sentence he penned, “For among us it is not necessary , as among the Hottentots, that a youth to be raised into the company of men, should prove his manhood by beating his mother!” I think so, too. Take Christianity from this land today – suspend the public worship of God everywhere – eliminate every radix and vestige of the Christian element from among the people, and what would you have left but a mass of fools and knaves, and a general scoundrelism swallowing itself up on all sides! Therefore I say, stand your ground, to all men who would be true to God, the gospel, and their country.

I do not come here to ask any favor for myself, and I again assert that every man, high or low, black or white, has an equal interest and a common obligation for the maintenance of the public worship of God in this Capitol. As a single member of the religious community, I do feel an intense interest in the support of the public recognition of God in this high place of the nation; and though I might never preach here again, it would be my prayer that some messenger of the great truth of Revelation might always stand here to uphold the mighty doctrine, and to flash its light and proclaim its summons over all the nation.

4. But the office of chaplain is liable to abuse, both in the manner of seeking it and in the character of its incumbents. I know it is alleged, and with some foundation of truth, I fear, that unworthy men have disgraced the profession, not only here but in the army and navy. But the true remedy is purgation, not the destruction of the office. Would you abolish Congress, because some members of Congress disgrace their station? I deplore as deeply as any man the delinquencies of men assuming the sacred office, only to make it the means of pandering to their own selfishness or corruption. I denounce it here, and I denounce it everywhere. But let us not tear down the house over our heads because some thief or robber has stolen into it, to rifle it of its contents.

5. But the services of chaplains are a bore to Congress. Ah! Then so much the worse for Congress. I am glad no record shows, so far as I have seen, that any member of Congress said such a thing as that. It was said by some scribbler for a newspaper. It comes with an ill grace from a class of individuals who get their living by filling the issues of the daily press with garbage. Do not take me to be criticizing that mighty power in the land without discrimination. When I consider the gigantic influence of this wonder of modern civilization, I am struck with awe at the constancy, the rapidity, and the ubiquity of its operations. It has more than realized all the fabled actors of antiquity. The hundred-handed Briareus, the hundred-eyed Argus, the thousand gifts of Apollo, the strength of Hercules, the wisdom of Minerva, the laughter of Momus are all its own – yea, and it has also the secrets of the fatal box of Pandora – and the prolific growth and foliage of all times and climes, and latitudes and seasons, until its leaves fall daily thicker than the leaves of all the forests – to bless or blight the nations. It is a mighty power for good or evil. Many great and good men are endeavoring to direct its energies – to them let us give all praise – but in the hands of the evil and the venal, who can calculate the mischief it has power to work!

6. But ministers are too apt to meddle with politics. If they would only preach the gospel, and let politics alone, they might be tolerated. Now I admit that there is a danger here, and that some fall into it – that is to say, ministers may fail in their great mission of preaching the gospel to the world, either by suppressing its great cardinal elements, and foisting in their place some truth, or error, as the case may be, which does not belong to the place they would assign to it; or they may so preach the gospel, in their style of handling it, as to render nugatory its legitimate influence and effect. All this is to be carefully avoided. But whoever undertakes to say that the gospel is not in itself essentially a system that takes hold upon the question of right and wrong everywhere in the nature, relations, society, intercourse and business of men, knows nothing of its principles or of its design. I know there has been an attempt to divorce the gospel from politics, and politics from the gospel; and I hold it to be one of the most stupendous practical errors, follies, heresies, and crimes of the age. The gospel is the most radical force of a moral and spiritual kind ever introduced into this world.

It is God’s plough-share, driven afield by the great cattle of his Providence, through the wilderness of human wrong and outrage for the last two thousand years; and wherever it comes, it is destined to tear up the prescription of ages of iniquity, the great systems of false religion and false philosophy, the infidelity, the tyranny, the oppression, the vice and rooted corruptions of mankind, and hurl them headlong from its mighty furrows. If it encounters a vulgar and vitiated system of politics, it will no more spare that than anything else that tends to the destruction and ruin of mankind. The gospel was designed to attack all false opinions and sentiments, all immoral customs and practices, all despotic and cruel principles, and every enemy of the virtue, the true culture, the Christian progress, and the spiritual elevation of mankind; and woe be to that professed minister of Christ who fails through any fear or favor of man, to declare the whole counsel of God, who abates one jot from the Revelation of divine wisdom. It is the duty of the minister to proclaim Christ and him crucified, the only and all-sufficient Savior of the world, and all the cognate and kindred doctrines of grace; but around this central doctrine of the cross, this article of justification by faith, every human interest and relationship come thronging; and he must apply this truth, rightly dividing the word – a workman that needs not to be ashamed.

The truth is, and we may all know it, a pure Christianity is the only sufficient and proper conservator of the duties, the obligations, and immunities of mankind – the only lasting and adequate security of republican constitutional liberty. This is the testimony of all the wisdom and greatness of the ages that are past:

“Government has an everlasting foundation in the unchangeable will of God,” said Otis. “May we ever be a people favored of God,” said Warren. “If it was ever granted to mortals to trace the designs of Providence, we may cry out, not unto us, but unto thy name be the praise,” said Samuel Adams. “There is one thing more I wish I could give them, and that is the Christian religion,” said Patrick Henry. “Let us play the men for God and the cities of our God,” said John Hancock. “Science, liberty, and religion are the choicest blessings of humanity,” said John Adams. “Righteousness exalts a nation,” testified Robert Treat Paine. “The hand of Heaven seems to have directed every occurrence,” said Elbridge Gerry. “I believe in the divine mission of our Savior,” said Thornton. “I believe in the Christian religion,” said Hopkins. “Let us be hopeful and trusting, for the Lord reigns,” said William Ellery. “A life-long devotion to his country and his God.” Is the eulogy of Roger Sherman. “

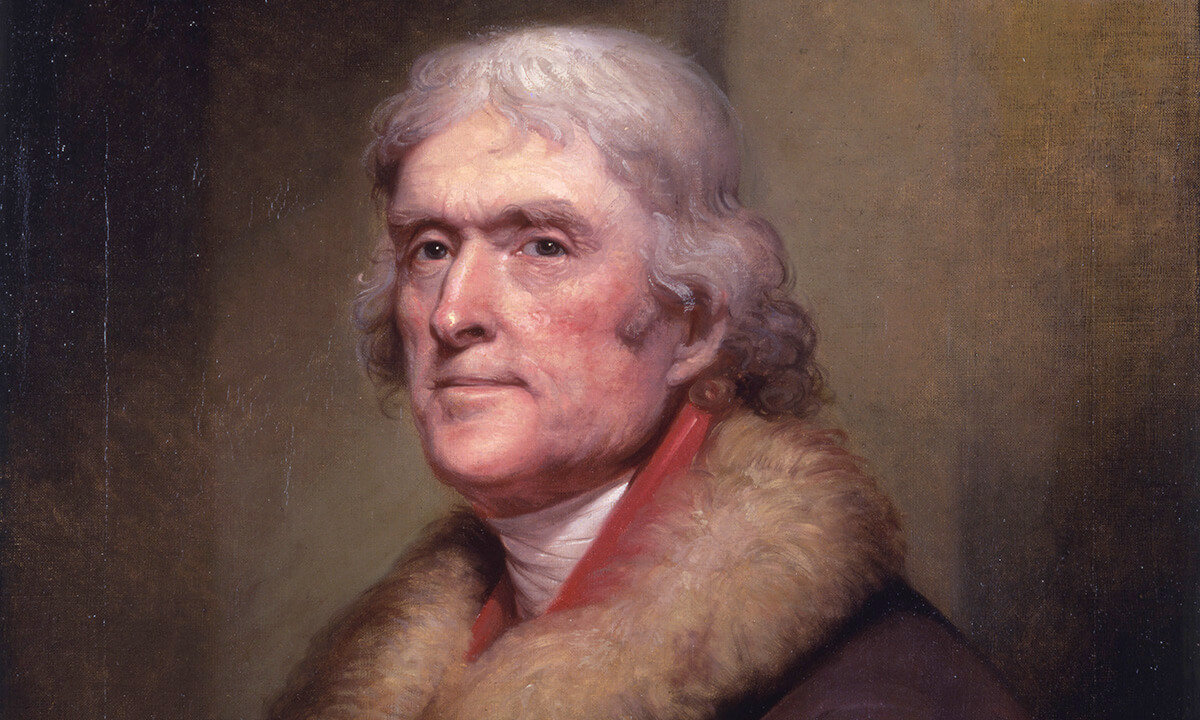

A professing Christian of eminent virtue,” was the substance of the testimony of the biographers of Huntingdon, of Williams, of Wolcott, of Livingston and Stockton. Of Witherspoon, the historian says, “If the pulpit of America had given only this one man to the Revolution, it would deserve to be held in everlasting remembrance.” “The worship of God is a duty,” said Benjamin Franklin. “I tremble for my country, when I reflect that God is just,” said Jefferson. “The duty we owe to God can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force and violence,” said George Mason. “Religion is the solid basis of good morals,” said Governor Morris. Of Pinckney it is certified, “He had practical faith in the divinity of the Bible, and its essential need to republican government” – of Benjamin Rush, that “he was one of the greatest and best of Christians.” Fisher Ames, John Hart, James Smith, and Robert Morris were all believers in the gospel of Christ; and some of them were as eminent in His church as in the councils of the nation. Hamilton, that great genius of the Revolution, says, “The law of nature, dictated by God himself, is of course superior to any other. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this.” “Grateful to Almighty God for the blessings which, through Jesus Christ, our Lord, he has bestowed upon my beloved country,” said the venerable Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Thompson, Wythe, Wilson, Chase, the two Lees, were all pre-eminent Christians. Every one of their illustrious associates and successors might be quoted as witnesses of the same great faith. John Jay, Boudinot, Madison, Monroe, Ellsworth, Drayton, Greene, Knox, Wm. Livingston, Trumbull, Washington and Lafayette, Marshall, the Randolph’s, the Adams, Jackson, Clay, and Webster – all these have left an imperishable record of their conviction that it is as true now as in the remotest antiquity, that, using the language of Plutarch, “a city might as well be built in the air, without any earth to stand upon, as a commonwealth or a kingdom be constituted or preserved without religion!” Need I say then, how deeply the American people, but especially the rulers, lawgivers, judges, and military and civil functionaries of our country, ought to feel the necessity and obligation of cleaving to this public recognition of Almighty God, and the great foundation principles of the Christian faith, in such a day as this? Now the earthquake of popular excitement is heaving in every quarter. Now the hurricane of popular opinion is sweeping fiercely and wildly across the naked heart of the nation. Now grim-visaged war rolls his dun clouds, reddened with the blood of our bravest and best, over all the sky. Now we are in the most momentous year of these great travail pangs – a year in which it is to be determined whether the nation, with the sword in one hand, and reeling under the weight of staggering blows from a giant rebellion, uplifted by the awful energies of the universal convulsion, can with the other steadily hold her great and sovereign birthright, and by the deliberate and unrestricted suffrage of a free people, advance to the high seat of Government a citizen for their President! Oh when I look at these things, I say God help us. Let the nation cling to the Christian religion.

It would be easy to show, as has been done over and over again, how the public worship of God tends directly to work those effects in the opinions, habits and spirit of the people which contribute to the public security and prosperity; and how, on the other hand, the neglect of these great ordinance s conspires to the demoralization of communities, until they are ground to powder beneath the upper and nether millstones of God’s providence. But I shall not enter into this argument now. It is sufficient to assert that no people can retain the principles of religion apart from its public monuments, ordinances, and commemorations. God has foretold therefore, that his worship shall be universal; and that in the high places of every nation there shall be the celebration of his praise. And therefore let me ask you whether it is a matter of individual and national concern for the people of the United States to maintain or not the public worship of Almighty God in these chambers of their Capitol? Shall the great hope of man and the great light of salvation here be permitted to go out from the highest public altar of the country – the temple of law and justice – the edifice consecrated to the noblest earthly work of man? No, no, sai I- a thousand times, no! I would not have this capitol polluted and disgraced by any company of brawling politicians, demagogues and conspirators, who under the sacred forms of legislative office, in the proud parade of senatorial robes – bearing the insignia of representatives of a mighty people, use such a place as this to hatch their infernal plots, and to perfect the finesse or the chicanery of their corrupt and mischievous designs.

Nay, rather I would have every man who enters these halls feel at once the grand old air of an upright and majestic manhood – feel that he stands in a temple – not like that at Jerusalem, which smoked with the holocausts of a thousand victims but a place where God’s homage is paramount, and man’s dignity the next in value to the Infinite; both uniting to give these halls a sanctity more than the veneration of the Amphictyon Council – more than the Hebrew Sanhedrin – more than the Court of Aeropagus, or the Delphic Oracles – more than the Roman Senate- more than the Saxon Witenagemot – more than the House of Deputies of France – more than the Parliament of England. And so long as the starry banner, the previous ensign of the Republic floats over the capitol, in token of the convention of the nation’s lawgivers, and so long as the statue of Liberty, now exalted over us by the wonderful skill and cunning handiwork of man, shall look down upon this grand panorama and proscenium of the metropolis, so long, even to the last running sand of expiring time, would I have this public structure devoted to the public worship of God – its pillars the emblems of his truth, its adornments the symbols of his favor, its chambers, halls and corridors filled with the rolling songs of praise, and echoing to the swell of voices uplifted in the wonder, the gratitude, the awe, and the adoration of His worship.

Yea, and when that glorious hour shall strike the full accomplishment of his great prediction, and from moon to moon, and from Sabbath to Sabbath, all nations shall come before the Jehovah of the whole earth, and there shall be one matchless and continuous anthem of worship, reverberating from hill to hill, and from land to land, and from shore to shore, as the sun performs his circuit in the heavens, and all the ministers of God, becoming the mouth of the millions of earth’s people, shall utter their successive testimony to the truth of the great salvation, and from all the renowned cities of the globe shall break, and echo, and respond, in the soul-thrilling accents of apocalyptic tongues, the last great announcement of the emancipated world, the kingdoms of the earth have become the kingdoms of our God, and when the great heart of human nature no longer driven by the sins and sorrows of the time, but redressed and full of living joy, shall beat with the mighty fervor of unutterable enthusiasm, and when from every summit of nature, and every tower of man, shall peal forth the solemn knoll of God’s great bells of time, calling mankind to worship – Oh, then would I have the capitol of my country stand high and strong, with all the heart of the nation gathered about it, God’s favor shining upon it, millions of prayers centered in it, and the voice of its worship going up to the Supreme Ruler of the Universe in a volume the clearest, the grandest, and the most earnest of all the voices that shall salute the ear of Heaven from the manifold languages of the whole earth! This is an emulation worthy to be fostered, and may the Lord Jehovah hasten it in his time! Amen.

END.

Most Americans are very familiar with the Library of Congress and its massive collection of millions of books, documents, recordings, photographs, sheet music, and manuscripts.

Most Americans are very familiar with the Library of Congress and its massive collection of millions of books, documents, recordings, photographs, sheet music, and manuscripts.

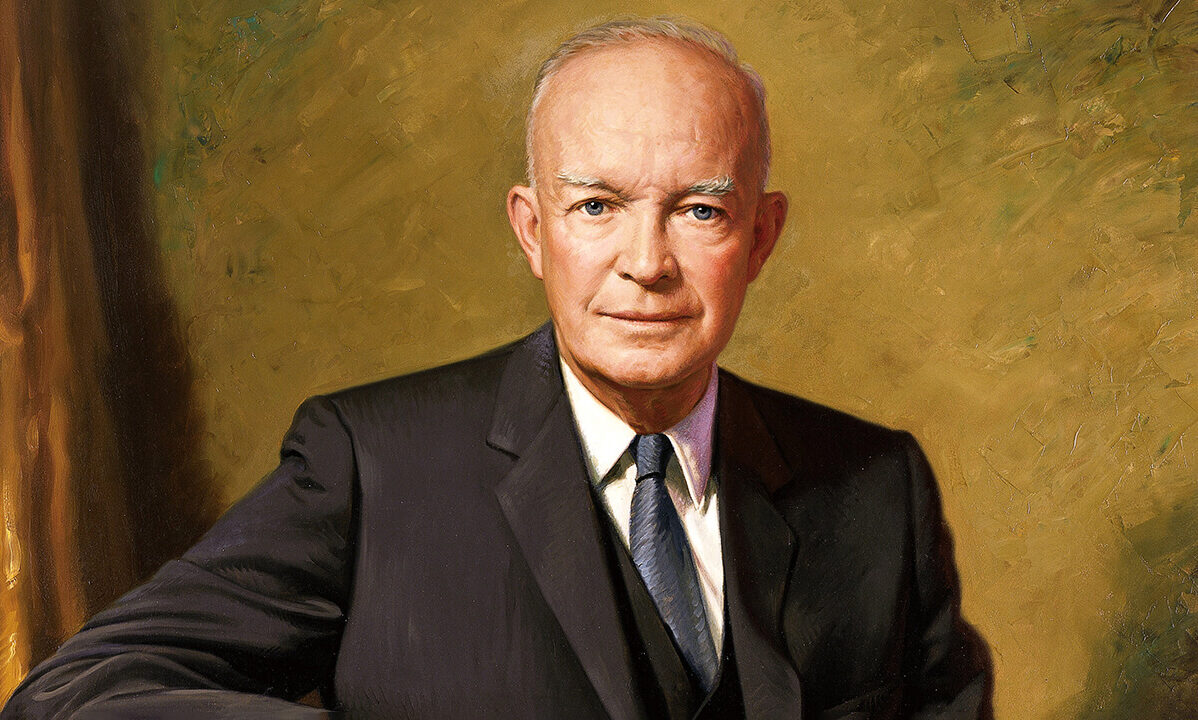

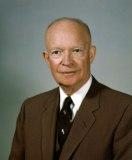

February 7 is a notable historical day for the acknowledgment of God in modern America: it is the day that a sermon was preached before President Dwight D. Eisenhower, suggesting that the words “under God” be added to the pledge. The sermon was preached by the Rev. George M. Docherty, pastor of New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D. C.

February 7 is a notable historical day for the acknowledgment of God in modern America: it is the day that a sermon was preached before President Dwight D. Eisenhower, suggesting that the words “under God” be added to the pledge. The sermon was preached by the Rev. George M. Docherty, pastor of New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D. C. There was something missing in the pledge, and that which was missing was the characteristics and definitive factor in the American way of life. Indeed apart from the mention of the phrase, the United States of America, it could be the pledge of any republic. In fact, I could hear little Muscovites repeat a similar pledge to their hammer and sickle flag in Moscow with equal solemnity.

There was something missing in the pledge, and that which was missing was the characteristics and definitive factor in the American way of life. Indeed apart from the mention of the phrase, the United States of America, it could be the pledge of any republic. In fact, I could hear little Muscovites repeat a similar pledge to their hammer and sickle flag in Moscow with equal solemnity. Our nation is founded on a fundamental belief in God, and the first and most important reason for the existence of our government is to protect the God-given rights of our citizens. . . . Indeed, Mr. President, over one of the doorways to this very Chamber inscribed in the marble are the words “In God We Trust.” Unless those words amount to more than a carving in stone, our country will never be able to defend itself.

Our nation is founded on a fundamental belief in God, and the first and most important reason for the existence of our government is to protect the God-given rights of our citizens. . . . Indeed, Mr. President, over one of the doorways to this very Chamber inscribed in the marble are the words “In God We Trust.” Unless those words amount to more than a carving in stone, our country will never be able to defend itself. From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty. To anyone who truly loves America, nothing could be more inspiring than to contemplate this rededication of our youth, on each school morning, to our country’s true meaning. . . . In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America’s heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country’s most powerful resource, in peace or in war.

From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty. To anyone who truly loves America, nothing could be more inspiring than to contemplate this rededication of our youth, on each school morning, to our country’s true meaning. . . . In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America’s heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country’s most powerful resource, in peace or in war. This month marks the 217th anniversary of George Washington’s famous

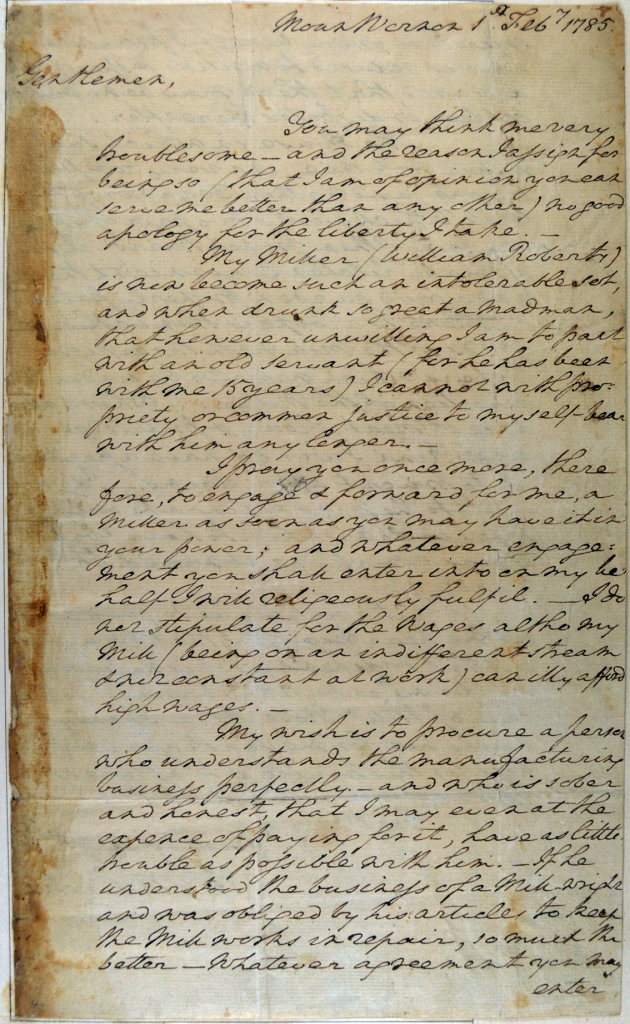

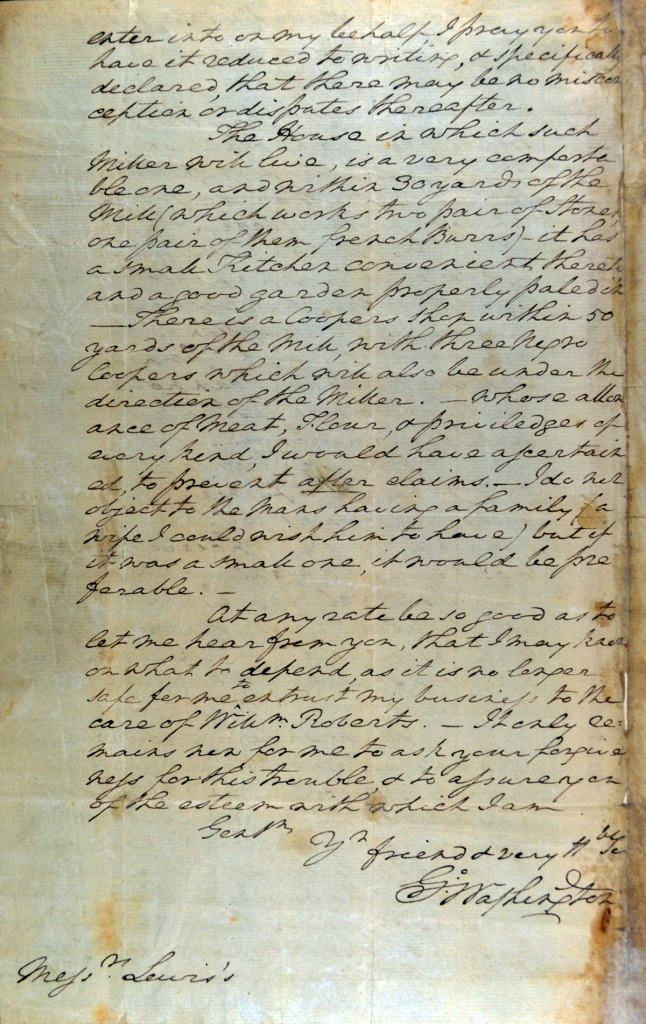

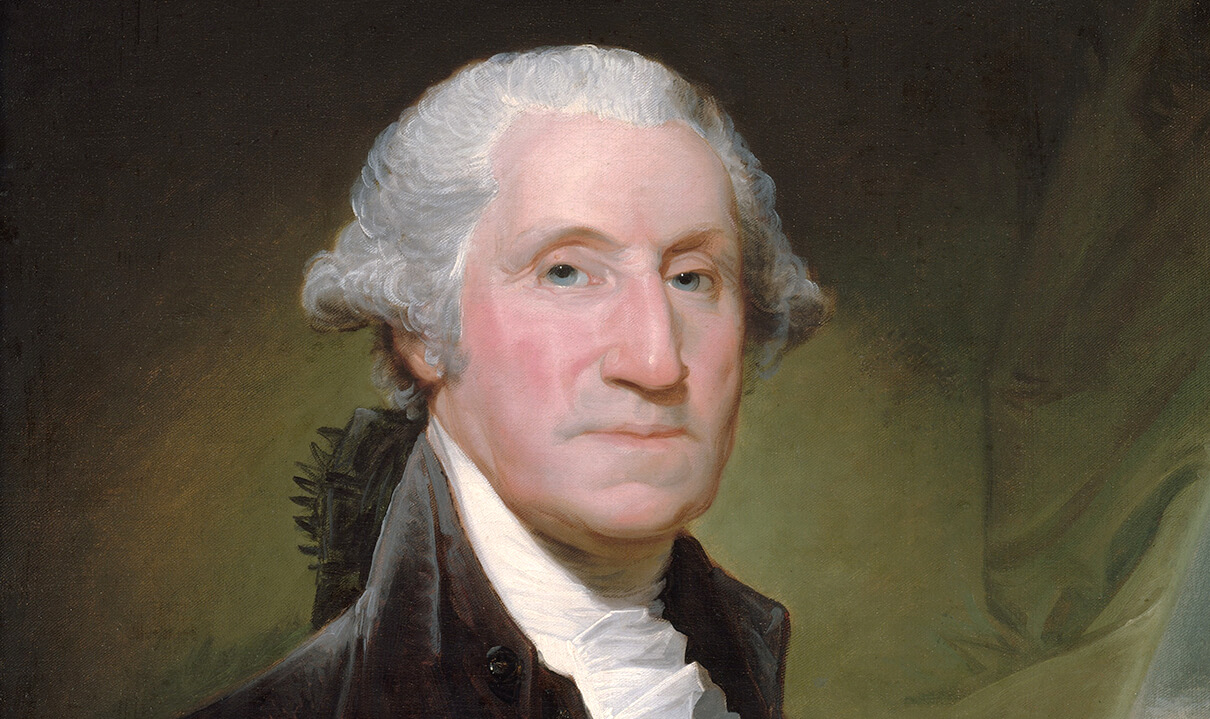

This month marks the 217th anniversary of George Washington’s famous  George Washington began his military career as an officer over the Virginia militia and then later as an aide-de-camp to British General Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War.

George Washington began his military career as an officer over the Virginia militia and then later as an aide-de-camp to British General Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War. Following the end of the Revolution and the writing and adoption of the Constitution, Washington was unanimously chosen as the nation’s first President — the only president to receive a unanimous electoral college vote.

Following the end of the Revolution and the writing and adoption of the Constitution, Washington was unanimously chosen as the nation’s first President — the only president to receive a unanimous electoral college vote.

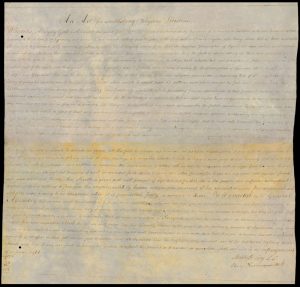

January 16, 1786, was the day that the Virginia Assembly adopted the

January 16, 1786, was the day that the Virginia Assembly adopted the  1779

1779