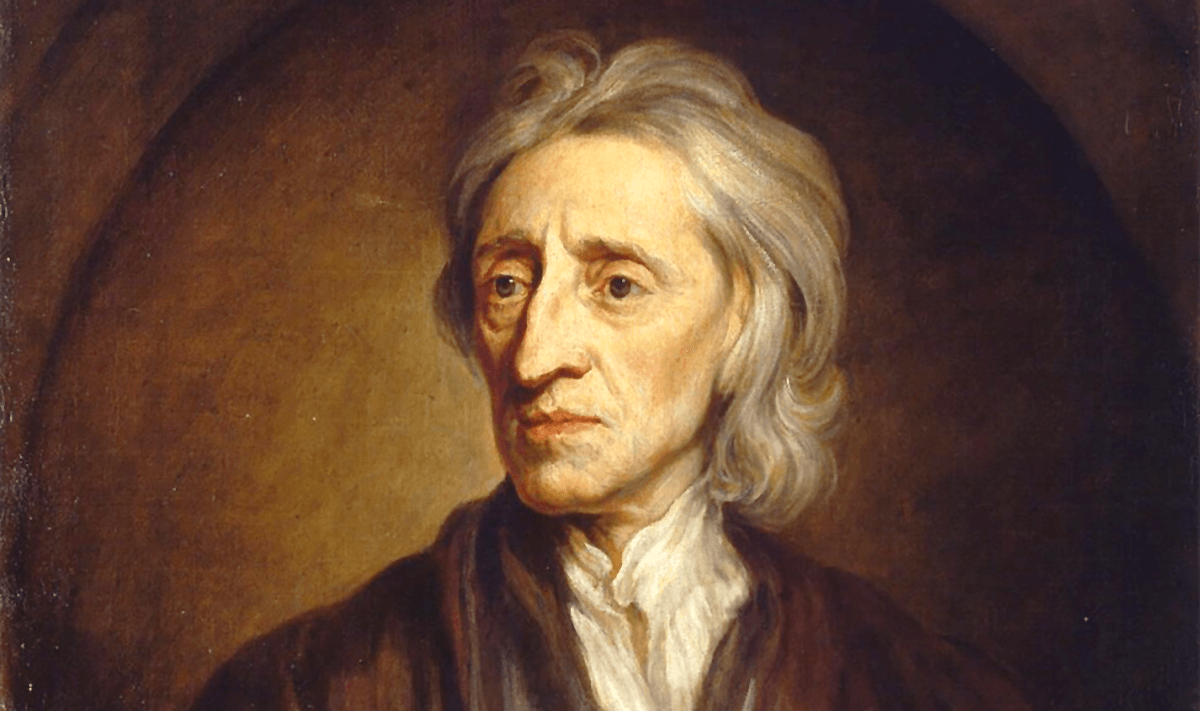

John Locke (1632-1704) is one of the most important, but largely unknown names in American history today. A celebrated English philosopher, educator, government official, and theologian, it is not an exaggeration to say that without his substantial influence on American thinking, there might well be no United States of America today – or at the very least, America certainly would not exist with the same level of rights, stability of government, and quality of life that we have enjoyed for well over two centuries.

Historians – especially of previous generations – were understandably effusive in their praise of Locke. For example:

- In 1833, Justice Joseph Story, author of the famed Commentaries on the Constitution, described Locke as “a most strenuous asserter of liberty”1 who helped establish in this country the sovereignty of the people over the government,2 majority rule with minority protection,3 and the rights of conscience.4

- In 1834, George Bancroft, called the “Father of American History,” described Locke as “the rival of ‘the ancient philosophers’ to whom the world had ‘erected statues’,”5 and noted that Locke esteemed “the pursuit of truth the first object of life and . . . never sacrificed a conviction to an interest.”6

- In 1872, historian Richard Frothingham said that Locke’s principles – principles that he said were “inspired and imbued with the Christian idea of man” – produced the “leading principle [of] republicanism” that was “summed up in the Declaration of Independence and became the American theory of government.”7

- In the 1890s, John Fiske, the celebrated nineteenth-century historian, affirmed that Locke brought to America “the idea of complete liberty of conscience in matters of religion” allowing persons with “any sort of notion about God” to be protected “against all interference or molestation,”8 and that Locke should “be ranked in the same order with Aristotle.”9

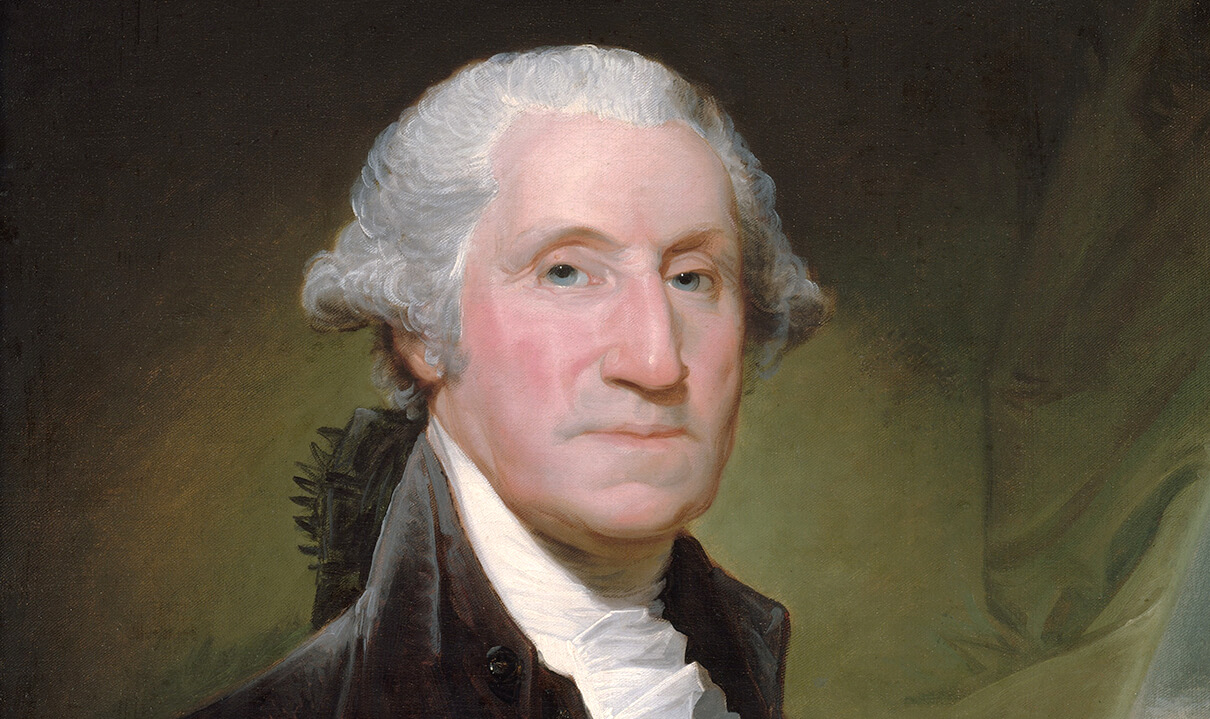

Such acknowledgments continued across the generations; and even over the past half century, U. S. presidents have also regularly acknowledged America’s debt to John Locke:

- President Richard Nixon affirmed that “John Locke’s concept of ‘life, liberty and property’” was the basis of “the inalienable rights of man” in the Declaration of Independence.10

- President Gerald Ford avowed that “Our revolutionary leaders heeded John Locke’s teaching ‘Where there is no law, there is no freedom’.”11

- President Ronald Reagan confirmed that much in America “testif[ies] to the power and the vision of free men inspired by the ideals and dedication to liberty of John Locke . . .”12

- President Bill Clinton reminded the British Prime Minister that “Throughout our history, our peoples have reinforced each other in the living classroom of democracy. It is difficult to imagine Jefferson, for example, without John Locke before him.”13

- President George W. Bush confessed that “We’re sometimes faulted for a naive faith that liberty can change the world, [but i]f that’s an error, it began with reading too much John Locke . . .”14

The influence of Locke on America was truly profound; he was what we now consider to be a renaissance man – an individual skilled in numerous areas and diverse subjects. He had been well-educated and received multiple degrees from some of the best institutions of his day, but he also pursued extensive self-education in the fields of religion, philosophy, education, law, and government – subjects on which he authored numerous substantial works, most of which still remain in print today more than three centuries after he published them.

In 1689, Locke penned his famous Two Treatises of Government. The first treatise (i.e., a thorough examination) was a brilliant Biblical refutation of Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha in which Filmer had attempted to produce Biblical support for the errant “Divine Right of Kings” doctrine. Locke’s second treatise set forth the fundamental principles defining the proper role, function, and operation of a sound government. Significantly, Locke had ample opportunity to assert such principles, for he spent time under some of England’s worst monarchs, including Charles I, Charles II, and James II.

In 1664, Locke penned “Questions Concerning the Law of Nature” in which he asserted that human reason and Divine revelation were fully compatible and were not enemies – that the Law of Nature actually came from God Himself. (This work was not published, but many of its concepts appeared in his subsequent writings.)

In 1667, he privately penned his “Essay Concerning Toleration,” first published in 1689 as A Letter Concerning Toleration. This work, like his Two Treatises, was published anonymously, for it had placed his very life in danger by directly criticizing and challenging the frequent brutal oppression of the government-established and government-run Church of England. (Under English law, the Anglican Church and its 39 Doctrinal Articles were the measure for all religious faith in England; every citizen was required to attend an Anglican Church. Dissenters who opposed those Anglican requirements were regularly persecuted or even killed. Locke objected to the government establishing specific church doctrines by law, argued for a separation of the state from the church, and urged religious toleration for those who did not adhere to Anglican doctrines.) When Locke’s position on religious toleration was attacked by defenders of the government-run church, he responded with A Second Letter Concerning Toleration (1690), and then A Third Letter for Toleration (1692) – both also published anonymously.

In 1690, Locke published his famous Essay Concerning Human Understanding. This work resulted in his being called the “Father of Empiricism,” which is the doctrine that knowledge is derived primarily from experience. Rationalism, on the other hand, places reason above experience; and while Locke definitely did not oppose reason, his approach to learning was more focused on the practical, whereas rationalism was more focused on the theoretical.

In 1693, Locke published Some Thoughts Concerning Education. Originally a series of letters written to his friend concerning the education of a son, in them Locke suggested the best ways to educate children. He proposed a three-pronged holistic approach to education that included (1) a regimen of bodily exercise and maintenance of physical health (that there should be “a sound mind in a sound body”15), (2) the development of a virtuous character (which he considered to be the most important element of education), and (3) the training of the mind through practical and useful academic curriculum (also encouraging students to learn a practical trade). Locke believed that education made the individual – that “of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education.”16 This book became a run-away best-seller, being printed in nearly every European language and going through 53 editions over the next century.

Locke’s latter writings focused primarily on theological subjects, including The Reasonableness of Christianity as Delivered in the Scriptures (1695), A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity (1695), A Second Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity (1697), A Common-Place-Book to the Holy Bible (1697), which was a re-publication of what he called Graphautarkeia, or, The Scriptures Sufficiency Practically Demonstrated (1676), and finally A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St. Paul to the Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Ephesians (published posthumously in 1707).

In his Reasonableness of Christianity, Locke urged the Church of England to reform itself so as to allow inclusion of members from other Christian denominations – i.e., the Dissenters. He recommended that the Church place its emphasis on the major things of Christianity (such as an individual’s relationship with Jesus Christ) rather than on lesser things (such as liturgy, church hierarchy and structure, and form of discipline). That work also defended Christianity against the attacks of skeptics and secularists, who had argued that Divine revelation must be rejected because truth could be established only through reason.

(While these are some of Locke’s better known works, he also wrote on many other subjects, including poetry and literature, medicine, commerce and economics, and even agriculture.)

The impact of Locke’s writings had a direct and substantial influence on American thinking and behavior in both the religious and the civil realms – an influence especially visible in the years leading up to America’s separation from Great Britain. In fact, the Founding Fathers openly acknowledged their debt to Locke:

- John Adams praised Locke’s Essay on Human Understanding, openly acknowledging that “Mr. Locke . . . has steered his course into the unenlightened regions of the human mind, and like Columbus, has discovered a new world.”17

- Declaration signer Benjamin Rush said that Locke was not only “an oracle as to the principles . . . of government”18 (an “oracle” is a wise authority whose opinions are not questioned) but that in philosophy, he was also a “justly celebrated oracle, who first unfolded to us a map of the intellectual world,”19 having “cleared this sublime science of its technical rubbish and rendered it both intelligible and useful.”20

- Benjamin Franklin said that Locke was one of “the best English authors” for the study of “history, rhetoric, logic, moral and natural philosophy.”21

- Noah Webster, a Founding Father called the “Schoolmaster to America,” directly acknowledged Locke’s influence in establishing sound principles of education.22

- James Wilson (a signer of the Declaration and the Constitution, and an original Justice on the U. S. Supreme Court) declared that “The doctrine of toleration in matters of religion . . . has not been long known or acknowledged. For its reception and establishment (where it has been received and established), the world has been thought to owe much to the inestimable writings of the celebrated Locke…”23

- James Monroe, a Founding Father who became the fifth President of the United States, attributed much of our constitutional philosophy to Locke, including our belief that “the division of the powers of a government . . . into three branches (the legislative, executive, and judiciary) is absolutely necessary for the preservation of liberty.”24

- Thomas Jefferson said that Locke was among “my trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced.”25

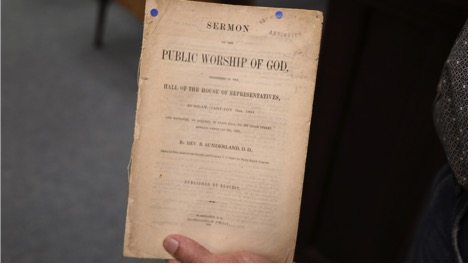

And just as the Founding Fathers regularly praised and invoked John Locke, so, too, did numerous famous American ministers in their writings and sermons.26 Locke’s influence was substantial; and significantly, the closer came the American Revolution, the more frequently he was invoked.

For example, in 1775, Alexander Hamilton recommended that anyone wanting to understand the thinking in favor of American independence should “apply yourself without delay to the study of the law of nature. I would recommend to your perusal . . . Locke.”27

And James Otis – the mentor of both Samuel Adams and John Hancock – affirmed that:

The authority of Mr. Locke has . . . been preferred to all others.28

Locke’s specific writing that most influenced the American philosophy of government was his Two Treatises of Government. In fact, signer of the Declaration Richard Henry Lee saw the Declaration of Independence as being “copied from Locke’s Treatise on Government”29– and modern researchers agree, having authoritatively documented that not only was John Locke one of three most-cited political philosophers during the Founding Era30 but that he was by far the single most frequently-cited source in the years from 1760-1776 (the period leading up to the Declaration of Independence).31

Among the many ideas articulated by Locke that subsequently appeared in the Declaration was the theory of social compact, which, according to Locke, was when:

Men. . . . join and unite into a community for their comfortable, safe, and peaceable living one amongst another in a secure enjoyment of their properties and a greater security against any that are not of it.32

Of that theory, William Findley, a Revolutionary soldier and a U. S. Congressman, explained:

Men must first associate together before they can form rules for their civil government. When those rules are formed and put in operation, they have become a civil society, or organized government. For this purpose, some rights of individuals must have been given up to the society but repaid many fold by the protection of life, liberty, and property afforded by the strong arm of civil government. This progress to human happiness being agreeable to the will of God, Who loves and commands order, is the ordinance of God mentioned by the Apostle Paul and . . . the Apostle Peter.33

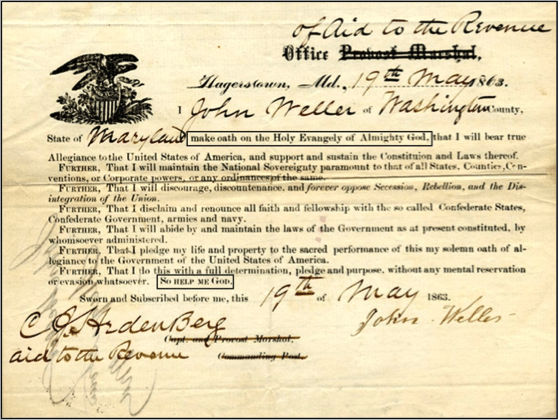

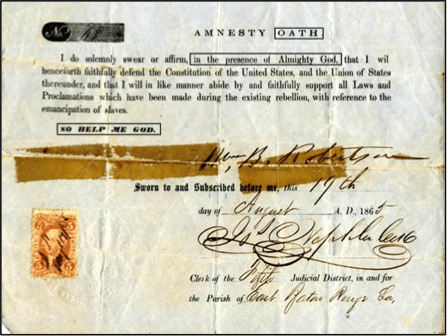

Locke’s theory of social compact is seen in the Declaration’s phrase that governments “derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Locke also taught that government must be built firmly upon the transcendent, unchanging principles of natural law that were merely a subset of God’s greater law:

[T]he Law of Nature stands as an eternal rule to all men, legislators as well as others. The rules that they make for other men’s actions must . . . be conformable to the Law of Nature, i.e., to the will of God.34

[L]aws human must be made according to the general laws of Nature, and without contradiction to any positive law of Scripture, otherwise they are ill made.35

For obedience is due in the first place to God, and afterwards to the laws.36

The Declaration therefore acknowledges “the laws of nature and of nature’s God,” thus not separating the two but rather affirming their interdependent relationship – the dual connection between reason and revelation which Locke so often asserted.

Locke also proclaimed that certain fundamental rights should be protected by society and government, including especially those of life, liberty, and property37– three rights specifically listed as God-given inalienable rights in the Declaration. As Samuel Adams (the “Father of the American Revolution” and a signer of the Declaration) affirmed, man’s inalienable rights included “first, a right to life; secondly, to liberty; thirdly, to property”38– a repeat of Locke’s list.

Locke had also asserted that:

[T]he first and fundamental positive law of all commonwealths is the establishing of the Legislative power. . . . [and no] edict of anybody else . . . [can] have the force and obligation of a law which has not its sanction [approval] from that Legislative which the public has chosen.39

The Founders thus placed a heavy emphasis on preserving legislative powers above all others. In fact, of the 27 grievances set forth in the Declaration of Independence, 11 dealt with the abuse of legislative powers – no other topic in the Declaration received nearly as much attention. The Founders’ conviction that the Legislative Branch was above both the Executive and Judicial branches was also readily evident in the U. S. Constitution, with the Federalist Papers affirming that “the legislative authority necessarily predominates”40 and “the judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power.”41

Locke also advocated the removal of a leader who failed to fulfill the basic functions of government so eloquently set forth in his Two Treatises;42 the Declaration thus declares that “whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it and to institute new government.”

In short, when one studies Locke’s writings and then reads the Declaration of Independence, they will agree with John Quincy Adams’ pronouncement that:

The Declaration of Independence [was] . . . founded upon one and the same theory of government . . . expounded in the writings of Locke.43

But despite Locke’s substantial influence on America, today he is largely unknown; and his Two Treatises are no longer intimately studied in America history and government classes. Perhaps the reason for the modern dismissal of this classic work is because it was so thoroughly religious: Locke invoked the Bible in at least 1,349 references in the first treatise, and 157 times in the second44– a fact not lost on the Founders. As John Adams openly acknowledged:

The general principles on which the Fathers achieved independence. . . . were the general principles of Christianity. . . . Now I will avow that I then believed (and now believe) that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God. . . . In favor of these general principles in philosophy, religion, and government, I [c]ould fill sheets of quotations from . . . [philosophers including] Locke – not to mention thousands of divines and philosophers of inferior fame.45

Given the fact that previous generations so quickly recognized the Christian principles that permeated all of Locke’s diverse writings, it is not surprising that they considered him a theologian.46 Ironically, however, many of today’s writers and so-called professors and scholars specifically call Locke a deist or a forerunner of Deism.47 But since Locke included repeated references to God and the Scriptures throughout his writings, and since he wrote many works specifically in defense of religious topics, then why is he currently portrayed as being anti-religious? It is because in the past fifty-years, American education has become thoroughly infused with the dual historical malpractices of Deconstructionism and Academic Collectivism.

Deconstructionism is a philosophy that “tends to deemphasize or even efface [i.e., malign and smear] the subject” by posing “a continuous critique” to “lay low what was once high”48 and “tear down the ancient certainties upon which Western Culture is founded.”49 In other words, it is a steady flow of belittling and negative portrayals about the heroes, institutions, and values of Western civilization, especially if they reflect religious beliefs. The two regular means by which Deconstructionists accomplish this goal are (1) to make a negative exception appear to be the rule, and (2) deliberate omission.

These harmful practices of Deconstructionists are exacerbated by the malpractice of Academic Collectivism, whereby scholars quote each other and those from their group rather than original sources. Too many writers today simply repeat what other modern writers say, and this “peer-review” becomes the standard for historical truth rather than an examination of actual original documents and sources.

Reflecting these dual negative influences of Deconstructionism and Academic Collectivism in their treatment of John Locke, many of today’s “scholars” simply lift a few short excerpts from his hundreds of thousands of written words and then present those carefully selected extracts in such a way as to misconstrue his faith and make it seem that he was irreligious. Or more frequently, Locke’s works are simply omitted from academic studies, being replaced only with a professor’s often inaccurate characterization of Locke’s beliefs and writings.

Significantly, the charge that Locke is a deist and a freethinker is not new; it has been raised against him for over three centuries. It first originated when Locke advocated major reforms in the Church of England (such as the separation of the state from the church and the extension of religious toleration to other Christian denominations); Anglican apologists who stung from his biting criticism sought to malign him and minimize his influence; they thus accused him of irreligion and deism. As affirmed by early English theologian Richard Price:

[W]hen . . . Mr. Locke’s Essay on the Human Understanding was first published in Britain, the persons readiest to attend to it and to receive it were those who have never been trained in colleges, and whose minds, therefore, had never been perverted by an instruction in the jargon of the schools. [But t]o the deep professors [i.e., clergy and scholars] of the times, it appeared (like the doctrine taught in his book, on the Reasonableness of Christianity) to be a dangerous novelty and heresy; and the University of Oxford in particular [which trained only Anglicans] condemned and reprobated the author.50

The Founding Fathers were fully aware of the bigoted motives behind the attacks on Locke’s Christian beliefs, and they vigorously defended him from those false charges. For example, James Wilson (signer of the Declaration and Constitution) asserted:

I am equally far from believing that Mr. Locke was a friend to infidelity [a disbelief in the Bible and in Christianity51]. . . . The high reputation which he deservedly acquired for his enlightened attachment to the mild and tolerating doctrines of Christianity secured to him the esteem and confidence of those who were its friends. The same high and deserved reputation inspired others of very different views and characters . . . to diffuse a fascinating kind of lustre over their own tenets of a dark and sable hue. The consequence has been that the writings of Mr. Locke, one of the most able, most sincere, and most amiable assertors of Christianity and true philosophy, have been perverted to purposes which he would have deprecated and prevented [disapproved and opposed] had he discovered or foreseen them.52

Thomas Jefferson agreed. He had personally studied not only Locke’s governmental and legal writings but also his theological ones; and his summary of Locke’s views of Christianity clearly affirmed that Locke was not a deist. According to Jefferson:

Locke’s system of Christianity is this: Adam was created happy and immortal…. By sin he lost this so that he became subject to total death (like that of brutes [animals]) – to the crosses and unhappiness of this life. At the intercession, however, of the Son of God, this sentence was in part remitted…. And moreover to them who believed, their faith was to be counted for righteousness [Romans 4:3,5]. Not that faith without works was to save them; St. James, chapter 2 says expressly the contrary [James 2:14-26]…. So that a reformation of life (included under repentance) was essential, and defects in this would be made up by their faith; i. e., their faith should be counted for righteousness [Romans 4:3,5]…. The Gentiles; St. Paul says, Romans 2:13: “the Gentiles have the law written in their hearts,” [A]dding a faith in God and His attributes that on their repentance, He would pardon them; (1 John 1:9) they also would be justified (Romans 3:24). This then explains the text “there is no other name under heaven by which a man may be saved” [Acts 4:12], i. e., the defects in good works shall not be supplied by a faith in Mahomet, Fo [Buddha], or any other except Christ.53

In short, Locke was not the deist thinker that today’s shallow and often lazy academics so frequently claim him to be; and although Locke is largely ignored today, his influence both on American religious and political thinking was substantial, directly shaping key beliefs upon which America was established and under which she continues to operate and prosper.

Americans need to revive a widespread awareness of John Locke and his specific ideas that helped produce American Exceptionalism so that we can better preserve and continue the blessings of prosperity, stability, and liberty that we have enjoyed for the past several centuries.

Endnotes

1 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, and Company 1833), I:299, n2.

2 Story, Commentaries (1833), II:57, n2.

3 Story, Commentaries 1833), I:293, n2; I:299, n2; I:305-306.

4 Story, Commentaries (1833), III:727.

5 George Bancroft, History of the United States of America (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858; first edition Boston: Charles Bowen, 1834), II:150.

6 Bancroft, History of the United States (1858; first edition 1834), II:144.

7 Richard Frothingham, The Rise of the Republic of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1872), 165.

8 John Fiske, Old Virginia and Her Neighbors (New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1897), II:274.

9 John Fiske, Critical Period of American History: 1783-1789 (New York: Mifflin and Company, 1896), 225.

10 Richard Nixon, “Message to the Congress Transmitting the Report of the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission,” The American Presidency Project, September 11, 1970.

11 Gerald Ford, “Address at the Yale University Law School Sesquicentennial Convocation Dinner,” The American Presidency Project, April 25, 1975.

12 Ronald Reagan, “Toasts of the President and Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom at a Dinner Honoring the Queen in San Francisco, California,” The American Presidency Project, March 3, 1983.

13 William Clinton, “Remarks at the State Dinner Honoring Prime Minister Tony Blair of the United Kingdom,” The American Presidency Project, February 5, 1998.

14 George W. Bush, “Remarks at Whitehall Palace in London, United Kingdom,” The American Presidency Project, November 19, 2003.

15 John Locke, The Works of John Locke (London: Arthur Bettesworth, John Pemberton, and Edward Simon, 1722), III:1, “Some Thoughts Concerning Education.”

16 Locke, Works (1722), III:1, “Some Thoughts Concerning Education.”

17 John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1856), I:53, to Jonathan Sewall on February 1760.

18 Benjamin Rush, The Selected Writings of Benjamin Rush, ed. Dagobert D. Runes (New York: The Philosophical Library, Inc., 1947), 78, “Observations on the Government of Pennsylvania.”

19 Benjamin Rush, Medical Inquiries and Observations (Philadelphia: T. Dobson, 1793), II:17, “An Inquiry into the Influence of Physical Causes upon the Moral Faculty.”

20 Rush, Medical Inquiries (1794), I:332, “Duties of a Physician.”

21 Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Jared Sparks (Boston: Tappan & Whittemore, 1836), II:131, “Sketch of an English School.”

22 Noah Webster, A Collection of Papers on Political, Literary and Moral Subjects (New York: Webster & Clark, 1843), 308, “Modes of Teaching the English Language.”

23 James Wilson, The Works of the Honourable James Wilson, ed. Bird Wilson (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), 1:6-7, “Of the Study of the Law in the United States.”

24 James Monroe, The Writings of James Monroe, ed. Stanislaus Murray Hamilton (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1898), I:325, “Some Observations on the Constitution, &c.”

25 Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Henry Augustine Washington (Washington, D. C.: Taylor & Maury, 1853), V:559, to Dr. Benjamin Rush on January 16, 1811.

26 See, for example, REV. JARED ELIOT IN 1738 Jared Eliot, Give Caesar His Due. Or, Obligation that Subjects are Under to Their Civil Rulers (London: T. Green, 1738), 27, Evans # 4241. REV. ELISHA WILLIAMS IN 1744 Elisha Williams, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants. A Seasonable Plea for the Liberty of Conscience, and the Right of Private Judgment, in Matters of Religion (Boston: S. Kneeland and T. Gaben, 1744), 4, Evans # 5520. Rev. JONATHAN EDWARDS IN 1754 Jonathan Edwards, A Careful and Strict Inquiry into the Modern Prevailing Notions of That Freedom of Will, which is Supposed to be Essential to Moral Agency, Virtue and Vice, Reward and Punishment, Praise and Blame (Boston: S. Kneeland, 1754), 138-140, 143, 164, 171-172, 353-354. REV. WILLIAM PATTEN, 1766 William Patten, A Discourse Delivered at Hallifax in the County of Plymouth, July 24th, 1766 (Boston: D. Kneeland, 1766), 17-18n, Evans # 10440. REV. STEPHEN JOHNSON, 1766 Stephen Johnson, Some Important Observations, Occasioned by, and Adapted to, the Publick Fast, Ordered by Authority, December 18th, A. D. 1765. On Account of the Peculiar Circumstances of the Present Day (Newport: Samuel Hall, 1766), 22n-23n, Evans # 10364. REV. JOHN TUCKER, 1771 John Tucker, A Sermon Preached at Cambridge Before His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Esq., Governor; His Honor Andrew Oliver, Esq., Lieutenant-Governor; the Honorable His Majesty’s Council; and the Honorable House of Representatives of the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New England, May 29th, 1771 (Boston: Richard Draper, 1771), 19, Evans # 12256. REV. SAMUEL STILLMAN, 1779 Samuel Stillman, A Sermon Preached before the Honourable Council and the Honourable House of Representatives of the State of Massachusetts-Bay, in New-England at Boston, May 26, 1779. Being the Anniversary for the Election of the Honorable Council (Boston: T. and J. Fleet, 1779), 22-25, and many others.

27 Alexander Hamilton, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), I:86, from “The Farmer Refuted,” February 23, 1775.

28 James Otis, A Vindication of the Conduct of the House of Representatives of the Province on the Massachusetts-Bay: Most Particularly in the Last Session of the General Assembly (Boston: Edes & Gill, 1762), 20n.

29 Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb (Washington, D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), XV:462, to James Madison on August 30, 1823.

30 Donald S. Lutz, The Origins of American Constitutionalism (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 143.

31 Lutz, Origins 1988), 143.

32 John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (London: A. Bettesworth, 1728), II:206-207, Ch. VIII, §95.

33 William Findley, Observations on “The Two Sons of Oil” (Pittsburgh: Patterson and Hopkins 1812), 35.

34 Locke, Two Treatises (1728), II:233, Ch. XI, §135.

35 Locke, Two Treatises (1728), II:234, Ch. XI, §135 n., quoting Hooker’s Eccl. Pol. 1. iii, sect. 9.

36 John Locke, The Works of John Locke (London: T. Davison, 1824), V:22, “A Letter Concerning Toleration.”

37 See, for example, Locke, Works (1824), V:10, “A Letter Concerning Toleration”; Locke, Two Treatises (1728), II:146, 188, 199, 232-233, passim; etc.

38 Samuel Adams, The Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906), I:351, from “The Rights Of The Colonists, A List of Violations Of Rights and A Letter Of Correspondence, Adopted by the Town of Boston, November 20, 1772,” originally published in the Boston Record Commissioners’ Report, XVIII:94-108.

39 Locke, Two Treatises (1728), II:231,Ch. XI, §134.

40 Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, The Federalist, or the New Constitution Written in 1788 (Philadelphia: Benjamin Warner, 1818), 281, Federalist #51 by Alexander Hamilton.

41 Hamilton, Jay, and Madison, The Federalist (1818), 420, Federalist #78 by Alexander Hamilton.

42 Locke, Two Treatises (1728), II:271, Ch. XVI, § 192.

43 John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution. A Discourse Delivered at the Request of the New York Historical Society, in the City of New York, on Tuesday, the 30th of April, 1839; Being the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Inauguration of George Washington as President of the United States, on Thursday, the 30th of April, 1789 (New York: Samuel Colman, 1839), 40.

44 Locke, Two Treatises (1728), passim.

45 John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1856), X:45-46, to Thomas Jefferson on June 28, 1813.

46 See, for example, Richard Watson, Theological Institutes: Or a View of the Evidences, Doctrines, Morals, and Institutions of Christianity (New York: Carlton and Porter, 1857), I:5, where Watson includes John Locke as a theologian.

47 See, for example, Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, ed. John Bowker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 151; Franklin L. Baumer, Religion and the Use of Skepticism (New York: Harcourt, Brace, & Company), 57-59; James A. Herrick, The Radical Rhetoric of the English Deists: The Discourse of Skepticism, 1680-1750 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), 15; Kerry S. Walters, Rational Infidels: The American Deists (Durango, CO: Longwood Academic, 1992), 24, 210; Kerry S. Walters, The American Deists: Voices of Reason and Dissent in the Early Republic (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992), 6-7; John W. Yolton, John Locke and the Way of Ideas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956), 25, 115.

48 Jack M. Balkin, “Tradition, Betrayal, and the Politics of Deconstruction – Part II,” Yale University, 1998.

49 Kyle-Anne Shiver, “Deconstructing Obama,” AmericanThinker.com, July 28, 2008.

50 Richard Price, Observations on the Importance of the American Revolution and the Means of Making it a Benefit to the World (Boston: True and Weston, 1818), 24.

51 Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. “infidel.”

52 James Wilson, The Works of the Honourable James Wilson, ed. Bird Wilson (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), I:67-68, “Of the General Principles of Law and Obligation.”

53 Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), II:253-254, “Notes on Religion,” October, 1776.

Why was Jefferson a faithful attendant at the Sunday church at the Capitol? He once explained to a friend while they were walking to church together:

Why was Jefferson a faithful attendant at the Sunday church at the Capitol? He once explained to a friend while they were walking to church together:

too, have American Presidents – as in 1947 when President Harry Truman quoted the Supreme Court, declaring:

too, have American Presidents – as in 1947 when President Harry Truman quoted the Supreme Court, declaring: