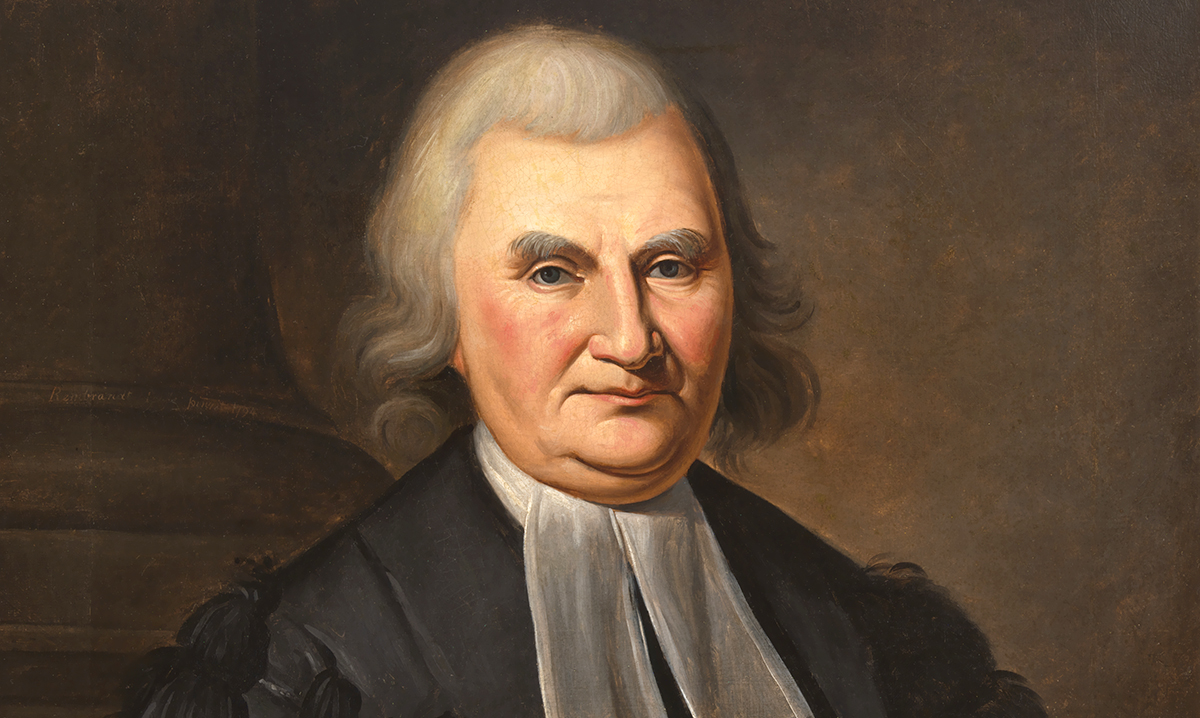

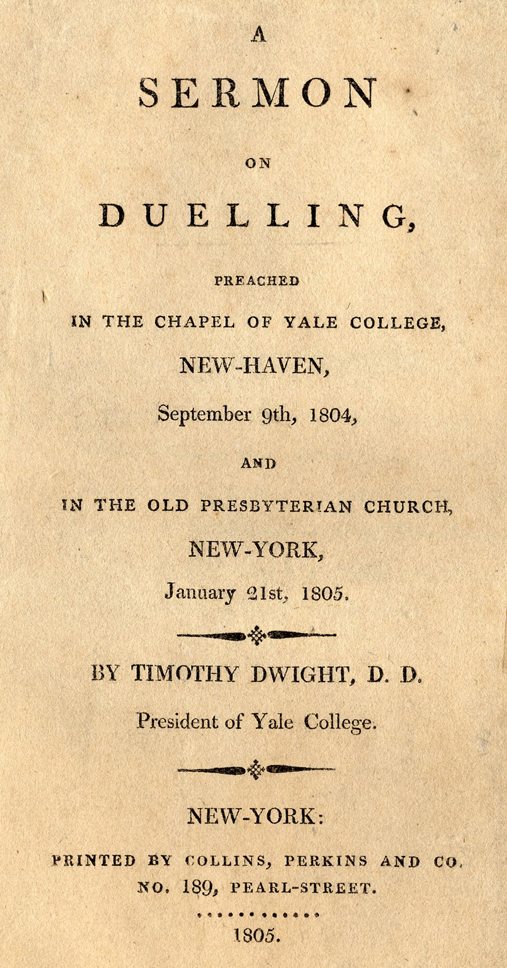

Timothy Dwight (1752-1817) graduated from Yale in 1769. He was principal of the New Haven grammar school (1769-1771) and a tutor at Yale (1771-1777). A lack of chaplains during the Revolutionary War led him to become a preacher and he served as a chaplain in a Connecticut brigade. Dwight served as preacher in neighboring churches in Northampton, MA (1778-1782) and in Fairfield, CT (1783). He also served as president of Yale College (1795-1817). This sermon was preached by Dwight on July 7, 1795 in Connecticut.

THE TRUE MEANS OF ESTABLISHING PUBLIC HAPPINESS.A

S E R M O N,

DELIVERED

ON THE 7TH OF JULY, 1795,

BEFORE THE

CONNECTICUT SOCIETY

OF

C I N C I N N A T I,

AND PUBLISHED AT THEIR REQUEST.

THE MEANS OF ESTABLISHING PUBLIC HAPPINESS.ISAIAH xxxiii. 6.

AND WISDOM AND KNOWLEDGE SHALL BE THE STABILITY OF THY TIMES.

To establish on firm foundations the Happiness of Society is evidently one of the most important concerns of man. If the attainment of that happiness by highly desirable, the perpetuation of it must be more desirable. Its daily value is daily renewed, during its continuance; and, when extended through a century, it is mathematically proved to be of a hundred times the value, which it would possess, if extended only through a year.

The mind of man, instinctively realizing this truth, has ever laboured rather to secure, than to obtain, happiness, both public and private. The attainment is usually not a difficult task, the establishment a Herculean one. A free government has been found sufficiently easy; but to render it durable has been ever considered as a problem of very difficult solution. Yet in its durability plainly consists almost all the value of such a government. Hence most of the political knowledge and labour of freemen has been employed, and exhausted, in endeavouring to give stability to their respective political systems. Hence have arisen the numerous checks, balances, and divisions of power and influence, found in our own political constitutions, and in those of several other nations. In other nations, these means have been generally insufficient to accomplish the end. Whether they will issue more happily in our own is uncertain. In several instances, we seem to have approached the verge of dissolution; but we have providentially withdrawn, before the season of safety was passed. Men of extensive political information, and sagacious forecast, have frequently trembled for our national existence; and, notwithstanding some favourable interpositions of Providence in our behalf, they still wait anxiously to know what the end will be. Should we fall, the fairest hopes of wise and good men will be blasted; the maxim, That mankind cannot be governed without force and violence, will stand on higher proof, and be advanced with new and triumphant confidence; and the great body of civilized men will probably sit down in sullen and melancholy conviction, that nations cannot, unless circumscribed by Alps, or oceans, be permanently free.

Most nations, and most politicians, have considered Arms and Wealth, as primary means of continuing national happiness. To this opinion they have probably been led by the allurements of avarice and ambition, by the power of custom, and by a persuasion, easily imbibed, that grandeur and happiness are synonymous. All these are deceitful guides, and have in this instance conducted only to error.

As means of defence, arms are evidently necessary to national safety, and, of course, to the permanence of national happiness; but, as means of conquest, they are usually the source of national ruin. States of moderate size, uninclined to military enterprise, and unambitious of high distinction, appear to have realized more happiness, than those of a contrary character. Widely extended dominions are too unwieldy and object, to be managed with either skill, or success; and power, diffused over a large territory, lessens at every stage of its diffusion. A greater and greater mixture of nations and tribes, once independent and impatient of subjugation, of different manners, religions, and interests, and prevented from uniting by prejudice and hatred, by imperious domination and irritated dependence, is continually accumulated, at every stride of conquest; and, like the iron and clay in the prophecy, though carefully moulded into a fair and regular form, is preparing to crumble, under the hand of the Former.

The system of government, also, and its necessary measures by becoming daily more complicated, become daily more perplexing. The public concerns are too numerous, the public officers, in opinions, characters, and interests, too various, the opportunities of secure oppression too easy, and the neglects of duty too frequent, to allow of any possible firmness, or consistency. The pile, however skillfully erected, and constantly repaired, is by the increase of its own weight precipitated to the ground.

From great accumulations of Wealth the same evil is derived with not less certainty, and in methods not very dissimilar. Avarice is one of those daughters of the horse-leach, which incessantly cry, “give, give;” it is eminently the fire, which saith not, “it is enough.” The love of property increases in a more rapid proportion, than the property itself. In a country possessed of immense wealth, places in government are, of necessity, highly lucrative, and, of course, the objects of ardent desire. To attain them, no principles, no efforts, are esteemed too great a sacrifice. Sycophancy, servility, bribery, perjury, and numberless other specters of vice, haunt all seats of power and trust, and force the friends of public integrity to retire with alarm and discouragement. Honesty is no longer counterfeited; but laughed at. Conscience is not silenced; but discarded. Posts of honour, are tossed out for a scramble; and truth, justice, and the public welfare, are vendued to the highest bidder.

On personal manners the effects are no less unhappy. Stimulated by avarice, and called onward by the commanding voice of custom, every man makes gold his god. To acquire riches becomes the only object, honour, or duty. By his wealth every man’s worth is sealed. Wealth is virtue; and poverty vice. The means of acquisition are, therefore, sanctified by the acknowledged importance of the end. Extortion, fraud, gaming, and peculation, steal into character, under the imposing names of industry and prudence, and whiten into virtues, in the sunshine, with which opulence is surrounded.

In the mean time, luxury holds out to appetite his store of various and sickly confections, and persuades those, who are prepared to be persuaded, that sense is the only source of real good, and that to eat and drink is the chief end of man. Enfeebled by sloth, debased by indulgence, and gross with a perpetual prostitution of taste and of talents, the rational character becomes assimilated to the animal one, and man claims a new and more intimate kindred to the swine.

Parade and appearance, also, invite and engross the national attention. Houses, gardens, equipage, and dress, take the place of duty and worth; and from the prince to the peasant the great ambition is to shine. Arts of ornament eject those of use; and manners of manliness and dignity give place to ceremony and profession. Education, instead of enlightening the understanding and forming the heart, is employed in gracing the person and supplying the limbs; and instead of teaching truth, implanting virtue and fashioning to worth by sober discipline, habituating care, and persuasive example, terminates all her labours in accomplishing for the dance and the drawing room. Children, are of course, led out of the path of reason and duty into the by-ways of appearance and sense, are conducted to the theatre and not to the church, and, while they are expected to become men and women, dwindle, with a regular diminution, into sribbles and dolls.

Thus the influence of enormous Wealth, and of extended Conquest, is equally pernicious to the Magistrate, and to the subject; and the national character becomes tainted, of course, with sickliness and corruption.

The experience of mankind has effectually elucidated the truth of these remarks. Greece, Rome, and the great nations of modern Europe, are all evident proofs of the intricate connection between Conquest and ruin; and Carthage and Holland are strong exhibitions of the perishing nature of society, which rests on the specious and treacherous support of unlimited Commerce.

The plans of those, who hitherto have chiefly planned for mankind, appear to have been formed principally for the purpose of fixing securely that state of society, which they found, a little, if at all, for its melioration. For this end, they appear to have aimed merely to strengthen the existing government against invasion and insurrection. Men, they seem to have supposed, must continue to e what they found them; ignorant, vicious, and unhappy. To render them as quiet as possible, in that state, is naturally concluded to have been the highest object of their policy, so far as it is exhibited in history. Hence they labored much to consolidate the elements of the government, and to secure to it that reverence, submission, and strength, which promised undisputed dominion. When the promotion of science became a part of the political system, it was principally adopted, for the purpose of qualifying individuals to govern, and furnishing useful agents to those who governed, in the prosecution of their measures; and rarely, and scantily, for the purpose of improving the mass of men. The Object was not so to rule, as to engross the esteem and affection of subjects; or to enable them to know when they were so ruled, as to make their rulers the proper objects of their esteem and affection. The Object was not to prepare subjects by information, happiness, and virtue, to understand, to love, and to preserve their state; but to make them quiet in that state, whether disposed, or indisposed. Hence, policy became an art; and government a trick. Rulers were employed in plotting against their subjects; and subjects either quietly sunk into torpid insensibility, or, awakened by oppression extended beyond every bound, rose to insurrection and madness.

This system, though it has been almost the only human system, has never appeared to be of real use to man. It has often defeated itself, and frustrated the designs of those, by whom it has been adopted. Assyria, Persia, Macedon, Rome, and France, are all proofs, that carefully supported, as it has been by all the arts of policy, and the utmost accumulation of power, it has still sown in itself the feeds of dissolution; and that those, whom it was intended to aggrandize, have fallen into the same gulf of perdition, with those whom it was intended to enslave. The Character of the mass of people, in each of those monarchies, was the real cause of its political ruin; and the nature of the political system was as really a principal cause of that character. In Africa, where Oppression has more effectually wielded her iron rod, and where man has been more entirely shorne of his intellectual dignity, a more uniform course of society has been accomplished. But here quietness has existed without happiness; a stagnant lake, filled with pollution and death; and nations, commuting reason for instinct have shrunk into brutes. In India, and in China, where the same system has long, tho’ not uninterruptedly prevailed, the inhabitants have indeed risen to higher grades of manual ingenuity, but, as moral beings, are nearly on the same level.

Under the influence of freedom, man has been roused from this lethargy, and shaken himself with a returning consciousness of energy and action. In this superior situation, his powers, his views, his efforts, enlarged with a portentous growth; but they grew chiefly by the aid of soil, climate, and accident. The cultivation which they received, was the cultivation of chance, of passion, and of appetite; not of system, wisdom, or virtue. Greece became a Giant in war, in science, and in arts; but was still an infant in moral improvement, and useful policy. No regular plan of amending the human character appears to have been thought of by her most admired sages; and, while her efforts in the field, and in the study, awed mankind to astonishment, her citizens were merely a collection of superior savages. Their depravity assumed, indeed, a more elegant form, but not an essentially different character. Rome systematized, and in a higher degree than any other State has ever done, war, oppression, and devastation. Her government, also, was more skillfully adjusted, and more firmly compacted than the Grecian systems; but it was still tossed by tumult, and shattered by frequent violence. Her citizens were left to the same accidental improvement; and, though possessed of a more specious stateliness than those of Greece, were debased with the same grossness and immanity [barbarity]. Accustomed, from our infancy, to study their history, to admire their talents, and to celebrate their exploits, we are prone to form a different estimate of these nations; yet by a very moderate examination we shall find, that they furnish us many things to admire, but few to approve, that, as moral beings, they are distinguished with little advantage from various nations whom they contemptuously styled barbarians. Indeed, one of the first political errors of later ages appears to be too high a respect for the state of society in Greece and Rome.

There is, I believe, a more rational policy, beginning with a different aim, and pursuing public quiet in a nobler and more effectual manner. The primary mean of originating and establishing happiness, in free communities, is, I imagine, the formation of a good personal character in their citizens. Good citizens must of course constitute a happier community than bad ones, and must better understand the nature and causes of their happiness. They may safely be governed by a milder policy, and cannot but be better judges of the desirableness of such policy. More the children of reason, and less the slaves of appetite and passion, they will naturally be more satisfied with real happiness, and less allured, by that, which, however shewy, is unsubstantial; will need fewer restrictions, and be more contented under such as are necessary; will prize more highly such liberty, as it suited to the condition of man, and proportionally disregard that, which is Utopian. Hence, such citizens may probably be governed by justice, and common sense; and will not necessitate the adoption of force and oppression, or the employment of circumvention and statecraft.

A family is, in some respects, a state in miniature. Children of bad personal characters can scarcely be governed at all, and never, without constant exertions of terror and force. Children of a good character are easily swayed, without either. Mild and equitable measures, few and gentle interpositions of mere authority, united with argument and persuasion, will, in a family composed of such children, effectually establish domestic order, peace, and happiness. This difference of regulations, this exemption from the necessity of exerting force and inspiring terror, depends wholly on the character of those, who are to be governed. To a State these truths are not less applicable. If the personal character of its citizens were perfectly good, there would be neither necessity, nor opportunity, of governing by force. That train of penalties, which constitutes a great part of the business of every Legislature, and of the contents of every statute book, would cease to exist, as it would cease to be necessary; and the mere expression of the public will would execute itself. The Sheriff would enjoy a sinecure, and the jail moulder without an inhabitant.

On this general principle was the prophecy of the Text written. Wisdom and knowledge, the prophet declares, shall, at some future period, some period which I apprehend to e still future, be the stability of the times, to which he refers: i.e. the public stability of the age; of one, or of more than one nation: or, in other words, the means of establishing on firm foundations public happiness.

By Wisdom, all Persons who read the Bible know the Sacred Writers commonly intend Virtue; and Virtue in that enlarged and Evangelical sense, which embraces Piety to God, Good-will to mankind, and the effectual Government of ourselves. “The fear of the Lord,” said Jehovah, when disclosing this inestimable and hitherto unexplored subject, “that is Wisdom.” “The fear of the Lord,” says Solomon, (Heb.) is the chief part of Wisdom.” “The Wisdom, that is from above,” says James, “is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, easy to be entreated, full of mercy and good fruits, without partiality, and without hypocrisy.” As Wisdom is properly defined to be that attribute of mind, which aims at the best ends, and chooses the best means to accomplish them; so Virtue, which steadily aims at the Glory of God, the Good of mankind, and the Good of ourselves, the best possible ends, and which more naturally than any other disposition directs to the best means of accomplishing them, was, with peculiar propriety, styled Wisdom by the penmen of the Scriptures.

Virtue may be defined—The Love of doing good. It will be easily seen from this definition, if allowed to be just, that it can be but one indivisible Attribute of mind. Yet, as the objects, towards which it is exercised, are materially different, it has been divided, for the purposes of consideration, into the three great branches already mentioned. It ought to be observed, that it is not a passion, nor an aggregate of passions; but a principle, or disposition, habitual, active, and governing. It is the mental energy, directed steadily to that which is right.

God, the greatest object in the Universe, and infinitely more important and worthy than all others, demands, of course, the supreme regard of every rational being. The first, the most obligatory, and the most noble exercise of Virtue is the Love and Reverence of this Glorious Being, generally termed Piety.

Our fellow creatures, collectively, form the next great object of our regard. Virtue, exercised towards them, has very properly been denominated Good-will or Benevolence; a name descriptive of all right affections towards them, and including justice, faithfulness, kindness, truth, forgiveness, and all those, which are frequently styled the Social Virtues.

To himself every Man is also an important object of regard. Virtue, as exercised towards ourselves, includes every just desire and vindicable pursuit of our real good; but it is principally employed in regulating and confining within due bounds our appetites and passions; principles in the human mind, which perpetually prompt to wrong, and which, without a continual and vigorous restraint, invariably dishonor God, injure our fellow men, and ruin ourselves. Thus exercised, Virtue is termed Temperance, or Self-government.

It is unnecessary for me to remark to this Audience, that all human conduct springs from the human will; that this is the only active principle in man; and that, as the will is directed to good, or evil, right, or wrong, man invariably does that, which is evil, or that which is good. The real importance of Virtue to the happiness of Society lies in this; that Virtue is an uniform direction of the will to that which is good. When man is virtuous, therefore, his disposition, the source of all his conduct, being steadily pointed to that, which is good, and right, his conduct must, of course, be also right and good. Hence Virtue of necessity aims at the happiness of Society. A man’s private interest may, for a time, and in his own view, be promoted by wrong; but the interests of a community can never be, for a moment, promoted but by that which is right. A selfish, separate interest clashes with that of every neighbor, and cannot be advanced, but to the injury of the common good. Avarice always robs; ambition always oppresses; and sensuality always wounds. Virtue, on the contrary, invariably seeks the common welfare, and gives no pain, where it is not indispensably necessary for the promotion of that welfare.

Virtue is, also, a principle sufficiently powerful and active to make all the happiness, which Society can enjoy. It is the whole energy of the Deity; and of every perfect being; and may become the whole energy of man. It often has become sufficiently powerful to produce the highest self-denial, of which man in his present state is capable; and is not uncommonly of such strength, as to constitute the only active character. Greater exertions have rarely sprung from selfishness, than have sprung from virtue. The labours of Alfred were not inferior to those of Caesar; nor were those of the proudest and most ambitious Philosopher to be named with those of Paul.

As Virtue is the genuine, the invariable, and the efficient source of public happiness, so it is in the same degree its stability. As it is its natural tendency to produce happiness, so this is always and equally its tendency. Wherever, and how long soever, it exists, the happiness, of which it is the parent, will also exist.

Good-will to Mankind, accomplishes directly most of those desirable objects, at which the political Constitutions, and the Laws, of Society aim; It makes men honest, just, faithful, submissive to government, and friendly to each other, without restrictions, or punishments; and renders magistrates equitable, public spirited, and merciful, without checks, factions, or rebellions. And all this it can accomplish, without labour, or expense, without force, turmoil or terror.

Self-government, on the other hand, effectually restrains from all those evils in Society, to prevent which is the principal employment of Laws and of Magistrates. With far more efficacy, and incomparably more ease, than the post and the prison, the gibbet and the cross, does it deter from fraud, revenge, impurity, theft, robbery, treason, and rebellion. At the same time, it guards from ten thousand other evils, which no Law can restrain, and which, often, are not less pernicious to Society, than those overt and glaring acts, which are the objects of judicial decision. Its influence on the Magistrate is equally propitious; nor are the private evils, which I have specified more effectually prevented, than the extensive and enormous mischiefs of corruption, peculation, and tyranny.

With regard to the advantage and necessity of Goodwill to public happiness, there has never been any debate, except that, which respects all Virtue, viz. Whether it is necessary, that men should be principled to pursue the good of Society; or whether it is sufficient, to require the actions conducive to this end, without any regard to the principle. This question I shall discuss in the sequel.

With regard to the necessity of Self-government to the happiness of Society a debate has always existed. In every Community men are found, who steadily insist, that the indulgence of those desires which are appropriately termed Appetites is justifiable, and in no way noxious to the public good. Were men brutes, and connected on equal terms with a republic of swine, goats, and swift-peters, this sentiment would at least plead some pretence in its behalf; and Reason would not be obliged so often to blush for the human character, when it read, to this effect, the labours of infidel philosophers, or heard the conversation of equally rational sensualists.

The man of sloth, the drone of Society, who adds nothing to the common stock, and lives on the labours and spoils of others, might yet be borne, were not his sloth the flood-gate of wickedness. Idle to do good, he is a pattern of industry in doing evil. In his merely slothful character, every morsel, which he tastes, is the plunder of his neighbour, and every act of his enjoyment a depredation on Society. To console them for the injustice, with a restless mind, and hands diligent in mischief, he consumes his time, and employs his talents, in gambling, horseracing, cheating, stealing, receiving from thieves, corrupting youth, disturbing good order, and pursuing an universal round of noxious labours and pernicious diversions.

If idleness, prodigality, the ruin of health, reputation, and usefulness, the depravation of every mental and bodily faculty, the mortification of friends, the destruction of the peace, comfort, and hopes, of his family, and the exhibition of a contagious and pestilential example, are not injurious to a Community, the drunkard, and the glutton, will undoubtedly stand on new ground, and may with new confidence bring forward a putrid carcass, and a putrid mind, to the public eye, and insist, that they are found useful, and healthy members of the Body politic.

The man of lewdness is in a condition even less hopeful. He unceasingly scatters fire-brands, arrows, and death, on all around him. He professes, indeed, to be in sport, and merely to pursue his own amusement; but the sufferings of those, who are unhappily within his reach, make that amusement a very serious concern to them. He lives but to injure, and acts but to destroy. The burglar plunders the purse; the murderer cuts off the life, and hurries his unhappy victim to an untimely grave. The man of Lewdness robs the parent of his child, the husband of his wife, and the family of their mother; murders household peace, character, and happiness; plunges the dagger of death into the soul, and hurries the victim of his lust into the abyss of the damned. The plunder of the burglar may be recovered, or the loss may be borne: the victim of the murderer may live beyond the grave, and the unhappy mourners may with this hope soothe their excruciating sorrows: but no means can restore, no mind can sustain, the plunder of peace; no balsam was ever found for the ulcer of infamy; no skill can rebuild a ruined family; nor can any artist repair the wrecks of a soul. Such is the innocence of the Leacher; and, were not too great multitudes interested in protecting and conniving at vice, the chase of the wolf and the tiger would be forgotten, and he, in their stead, would be hunted from the residence of men.

Piety, the remaining branch of Virtue, although its utility, and its necessity to public happiness, has been more frequently questioned, and denied, is, probably at least as useful, and as necessary to this object, as either of the other branches. It will, I presume, be allowed to be wholly rational, and probable, that there are, within the limits of the creation, worlds, where the Creator is wholly respected according to his character; and where infinite greatness and excellence not only demand, but obtain, a love, reverence, and obedience, suited to their nature. That there is one such world, the Bible directly declares. In such a world, it is evident, Piety is the whole source of order, peace, and happiness. Perfect itself, it there renders the whole moral system perfect, and spontaneously produces that obedience to the divine government, which is less effectually produced here by threatenings and judgments. As Piety is the foundation, in that world, of the order and peace, on which all social happiness depends, it is rationally concluded, that it must be the natural foundation, in any other world, of proportional order and peace; and that, so far as it exists, it will benefit earth, as well as heaven, men, as well as angels, and any particular nation, as well as mankind in general. In other words, as Piety appears to be the foundation of the most perfect intellectual happiness; so it is to be deemed the real, the natural, and the universal foundation of social good.

From Piety, also, the other exercises of Virtue derive a higher distinction, are presented with stronger motives, and enforced by more solemn sanctions, than can spring from any other source.

All the duties which we owe to mankind, are, without the consideration of Piety, viewed as merely due to men; worms of the dust, beings of yesterday, and children of vanity and sin. To such beings moral obligation, though real, must be of comparatively little importance, and operate with little force. But in the eye of Piety all these duties are enhanced, beyond measure, by the consideration, that they are enjoined by God, and that, of course, every fulfillment of moral obligation to our neighbour is the performance of a duty to our Maker. The same remarks are, with equal force, applied to the duties of Self-government. As much greater, therefore, as much more excellent, and as much more possessed of a right to require our service, as God is than men, just so much more importance, and distinction, does Piety give to these branches of Virtue, than they could otherwise receive.

The principal motives to virtue are evidently the pleasure found in the practice of it—the esteem, affection, and beneficence which it excites in our fellow creatures—the approbation and love of God—and the expectation of future rewards and punishments. The two first of these motives must certainly operate with as great, and the two last with much greater influence, on Piety, than on any other supposable character. To the eye of Piety God appears, as a Being totally different from that, which is usually formed by every other eye. His character is invested with an importance wholly new. His approbation, love, and rewards, on the one hand, and his abhorrence, anger, and punishments, on the other, appear as objects real and boundless. Primary objects of attention, they become primary concerns; and are not only seen by conclusion, but directly felt to involve all the interests of man. Hence they become the directory of thought, and the law of action.

A clear and fixed sense of moral obligation is, probably, in the opinion of most men, indispensably necessary to the discharge of the duties, and to the production of the happiness of Society. But such a sense, it is presumed, is to be looked for in Piety alone. The strength of moral obligation lies wholly in the conviction, that a constant adherence to it is obedience to the will of God. But almost all the regard, which is rendered to God, or to his will, is rendered by the pious. Imperfect and desultory feelings of this nature, feelings which are yet of no small importance, will generally be found, where a religious education has given birth to just moral sentiments; and especially where general influence and example, united with public instruction, have cultivated such sentiments into habit. Beyond these limits nothing can be expected, nothing is commonly professed, and nothing will ever be found, beside the changing power of fashionable opinion, the slippery dependence of personal honour, and the accidental coincidence of selfishness with duty.

The great support of moral obligation, in the present world, is the belief of God’s moral government, of our accountableness to him, and of an approaching state of rewards and punishments. The desire of happiness, and the dread of misery, is a part of the intelligent, and even of the animal nature, and is inseparable from the faculty of perception. As all happiness, and all misery, are ultimately derived from the hand of God, and as no bounds can be set to the degree, or the continuance, of either, beside those, which he is pleased to set, this object comes home to every heart with a power totally peculiar. Its efficacy reaches all places, times, and persons: all persons, I mean, beside the fool, who hath said in his heart, “There is no God.” Its superior efficacy on men of piety I have already explained.

In a world, like this, where the depravity of man is proclaimed by every Law, is engraven on the altars of every Religion, and is written with a pen of adamant on the iron page of History, how desirable is it, that this great motive to duty, this great sanction of moral obligation, should, instead of being lessened by sophistry, ridicule, and neglect, be preserved and strengthened to the utmost, to save Society from those numerous evils, of which it is the only remedy, and to prompt men to those indispensable duties, to which it is often the only effectual motive?

In addition to these observations it may be justly asserted, that, without Piety, the other branches of Virtue are never found. There has been no proof either from fact, or from argument, hitherto adduced, to shew, that one branch of Virtue can exist independently of the others. All the heathens, both individuals and nations, who regarded their fellow men in the most equitable manner, and who regulated themselves with the greatest decency, were distinguished by reverence for the gods. Among Christians, also, there is no want of evidence, to prove, that impious men are alike destitute of benevolence and self-government, and that the appearances, which are found, of these characteristics, in those who are not pious, are the accidental result of convenience, or necessity.

But the subject will easily, and, I apprehend, perfectly explain itself. Justice in man is the love of that which is just. But can he, in whom this principle exists, be unjust to his Maker? Can he be willing, and principled, to render to Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and not to God the things which are God’s? Or can anything be Caesar’s with such absolute right, as he, his talents, time, and services, are God’s? Gratitude is an affectionate sense of benefits, and a proportionate love to the Benefactor. But can any man be grateful to a human, who is not grateful to the Divine, Benefactor? Generally, can a man love intelligent being at all, who does not love the Infinite Intelligent; or be at all virtuous, unless his virtue be directed primarily to that Being, who is, infinitely beyond all others, excellent, lovely and beneficent?

Whether it be desirable for Society, that its members should be principled to promote its happiness, or not; is a question, which cannot be asked without a blush, nor answered without a smile. It is to ask whether it would be better for Society, that its happiness should be great, stable, and secure; or small, fluctuating, and accidental. There is no steady source of public or private good, but principle; and there is, in this sense, no principle, but Virtue. To Virtue public good necessarily appears, and is enjoined by an Authority instinctively obeyed (the Authority of God) as a primary object of regard. To a mind not virtuous it is, of course, and always, an object subordinate, accidental, and solitary.

On the inhabitants of a land, universally virtuous, the peculiar blessings of Heaven may, also, be rationally expected to descend. Where human weakness errs, where human power falters, and where human means prove ineffectual, God may, both on rational and evangelical grounds, be expected to open his beneficent hand, and supply the necessary good. Here, also, Virtue may be safely pronounced to be the stability of public happiness.

But it is not enough, that the members of a Society aim at that, which will promote the general good; they must also know what it is. Knowledge is, therefore, with the utmost propriety designated in the text, as another source of this stability.

In examining this part of the subject, it will be useful to consider the kind, the diffusion, and the effects, of that knowledge, which is intended by the Prophet.

It will undoubtedly be conceded, that he intended that knowledge, which is real, and not merely nominal; that, also, which is practical, and therefore useful; and, of course, that, which is moral, or in other words, the most practical, and the most useful.

Almost all real knowledge, and all practical knowledge, is derived either from Experience, or from Revelation. Theories are generally mere dreams, which ought to be placed on the same level with the professed fictions of poets, and to be written in verse, and not in sober prose. Tho’ dignified with the pompous title of Philosophy, they have usually, after amusing the world, a little time, gone down the stream of contempt into the ocean of oblivion. They cannot be practical, because they cannot be true; and hence, being of no use, except to please the imagination, they are of course neglected and forgotten.

There is in the human mind a faculty, called Common-sense, which, though never in high estimation among Philosophers, seems to have originated, and executed, almost all the plans of human business which have proved to be of any use. The reason is obvious. Employed in forming near and evident deductions from facts, and in closely observing facts for that purpose, contented with moderate advances, and cautious of innovation, its step, though flow, has been sure; a real approximation to the end in view. Theory, on the contrary, rapid, but wild, has usually receded more than it has advanced. Untried causes, causes to which a new application is given, and experiments in business, made either anew, or in new circumstances, have always been regarded by Common-sense with a suspicious eye; and a state of things, not perfectly desirable, willingly endured, in preference to the adoption of new systems, of which the effects were uncertain, and the operations dangerous.

The system of government, formed for South-Carolina, by Mr. Locke, may stand as a portrait of all political theories. Fair and rational on paper, but deformed and useless in practice, it suited the real circumstances of that Colony, just as a map, drawn by the fancy of a Geographer, would suit an undiscovered country; or a chart of soundings, marked by the Navigator, in sport, would suit the real state of an untraversed ocean. If this Giant in understanding failed so entirely in an attempt to form a theoretical system of government, reducible to practice, of what character must be the attempts of modern pygmies?

That the knowledge, communicated by Experience and Revelation, was intended in this prophecy, will be evident to all persons, who remember, that this was the only knowledge in existence, when the prophecy was written. Visionary Philosophy had not then begun to mislead mankind. The world was contented with real knowledge; and, although its stock was small, it was genuine and unalloyed, and therefore of a currency and use, suited to human purposes. Had its progress been uninterrupted by war and devastation, and unbewildered by theoretical Philosophy, we should now probably be removed, in real knowledge, many degrees beyond our present advances.

A general diffusion of knowledge, was undoubtedly designed in this prediction. In no other sense could knowledge be supposed to be the means of general stability.

The effects of knowledge, thus defined, are evidently of high importance to social happiness. The Legislator it will enable to understand the state, the interests, and the duties, of a people; to form regulations suited to their state, promotive of their interests, and coinciding with their duty; to discern, with a freedom from low and pernicious prejudices, that equitable government is the true source of honour to himself, and of prosperity to his people; to cast his eyes abroad, without the purblind confusion of narrow minds, and see clearly the real condition of other nations, and their proper connection with the affairs of his own; to look back with distinctness, and with comprehension, on the past state of human society, and forward, with rational prediction, to events which are rising on the surface of futurity. In a word, placed by such knowledge on a lofty summit, he stands as a Watchman for the welfare of millions, unobstructed by mists, and undazzled by the height to which he is elevated, with a steady eye marks distinctly the surrounding progress of things, and is enabled with confidence, and with safety, to utter alike the quieting voice of peace, and the timely alarm of danger.

In the same manner is the Judge enabled to understand and interpret law, to form equitable decisions, to exercise his discretionary authority in extending or restricting penalties, and generally to hold with an equal hand the balance of right, between neighbour and neighbour, and between subjects and the state.

To maintain the dignity of government, to impress respect for his own office, to secure the general approbation in the execution of punitive justice, to stop at the bounds of law and right, and to mingle mercy with judgment by choosing the least distressing methods of enforcing judicial decisions, are employments which constitute the duty of the Executive magistrate; employments, which demand, perhaps in an equal degree, clear understanding and extensive information, and which hazard, without it, the public prosperity, and the public peace.

Nor are the people at large less interested in the knowledge above described. Stability of public happiness, especially in free States, depends wholly on the character of the citizens in general. Nor can it exist, unless they understand distinctly the rights and the duties freemen, the duties of magistrates, the requisitions of law, the common interest and the means of promoting it, the ruinous nature of war, the beneficent influence of peace, the relations of men in Society to each other, and the character, which those ought to sustain, who are contemplated as objects of the public suffrage. Equally useful is knowledge in teaching them the duties of Parents, children, friends, and neighbours, the nature and importance of a happy domestic education, the advantages of mild and obliging conduct, the universal profit of virtue, and the mischiefs of vice of every kind, in every degree, and towards every person. Highly important is knowledge, also, to give that personal respectability, and to secure that rational esteem, which excites and gratifies laudable ambition; to fill with profitable amusement the hours of leisure, and of age; to capacitate for the discharge of useful and necessary business; and to furnish means of improvement in the several arts and employments of life. In a word, from knowledge must, in a great measure, be derived that steadiness of character, that possession of comforts, and that rational estimation of things, which form the useful citizen, and the respectable Society.

From these observations, I flatter myself, it will appear, that the stability of public happiness is produced by Knowledge and Virtue; and that the diffusion of these through a Community is the true and the only method of solving that political problem, which has so long perplexed the rulers of mankind. By these great attributes men are made good members of society; and, composed of such members, a Society must be happy. They form, they finish, the magistrate and the citizen alike. They teach every duty, and prompt to every performance. They originate wise and equitable laws, just decisions and useful administrations. They create the amiable conjugal and household offices, produce effectual domestic education, train to early and happy habits, and conduct to family peace, neighbourly kindness, a cheerful submission to law, a steady love of rational government, and an universal growth of social enjoyment. Sweet and salubrious streams, they nourish happiness wherever they pass; and, enlarging and mingling in their progress, spread, in the end, an ocean of blessings over the millions, who inhabit an empire.

It will not be improper to add, that the most respectable political writers have, with one voice, declared Virtue to be indispensably necessary to the existence of a free Government. As this sentiment has been adopted in opposition to many prejudices, and interests, religious and secular, and adopted by them all, it may be fairly supposed to be the result of conviction and evidence. Perhaps it may have arisen, in part, from the following view of the subject.

Government is rendered effectual by two great engines—force and persuasion. Force is the instrument of despotism, and persuasion. Force is the instrument of despotism, and persuasion of free and rational government. To produce persuasion, it is always necessary to inspire confidence. To inspire confidence in subjects towards rulers, it is necessary for subjects to be satisfied, that their rulers are possessed of knowledge to discern, and of virtue to aim at, the general good. To inspire confidence in rulers towards subjects, it is necessary for rulers to be satisfied, that their subjects possess knowledge to discern, and virtue to approve, the real wisdom and equity of public measures. With these prerequisites, rulers will with confidence pursue the public interest; and subjects will with equal confidence support their administration: without them, the ruler, fearful and suspicious, always in perplexity and always in danger, will feel himself obliged to have recourse to art, cabal, and contrivance, to keep in motion the wheels of government; and subjects, anxious, jealous, and impatient, will continually fluctuate between hope and fear, flock at every call to the standard of faction, and prove the prey of every demagogue.

Facts, also, lend their evidence to support this doctrine. Sparta and Rome were the most stable of all the ancient republics. Virtue, in the sense of the Gospel, they had not; but, in their early periods, they were, to an unusual degree, possessed of what is called heathen virtue. Beyond most, perhaps beyond all, the heathen nations, they feared their gods, reverenced an oath, and believed in a providence, which rewarded the good, and punished the evil. Their ideas of truth and justice, however crude, were fixed; and they admitted fewer corruptions and violations of the principles, which they esteemed sacred, than most other nations. While this was their conduct, their public happiness, though imperfect, was stable; and, with the fall of these principles, it tumbled to the ground.

Among the modern nations of Europe, Switzerland, especially in some of its Cantons, holds the highest rank in public happiness. For more than 400 years, this distinguished country has withstood every shock from within, and from without, and appears still to rest on firm foundations. Equally remarkable has this country been for knowledge and virtue. In no State, in Europe, have the inhabitants at large possessed equal information, or exhibited equal proofs of piety and unblemished morals. To these causes their happiness is directly traced by every enlightened traveler. Happy Switzerland! God has created for thee thy walls and thy bulwarks. Under his good providence, thy bravery has made thee free, and thy knowledge and virtue have made me happy.

On this side of the Atlantic, Connecticut, by an extensive and increasing acknowledgement, appears to hold, in this respect, the first station. The happiness of this State, for one hundred and fifty years, has suffered, except from external enemies, little diminution. Its government, customs, manners, and general state of Society, have scarcely been changed, but by the gradual progress of refinement. Formed, at first, in all the great outlines, and nearly filled up, by men, whose distinguished rectitude of disposition, led, of course, to justness of opinion, and whose found Common-sense, improved by close observation, did not lead to error, its Constitution, although, in many respects, a violation of political theory, has been found more than any other to be fitted for practice. Public and private happiness its inhabitants have, in a high, perhaps an unrivalled, degree, enjoyed. In no country has Virtue, for so long a period, been held in higher estimation, received more marks of public regard, or more emphatically formed the general character. Knowledge, at the same time has, in an almost singular manner, been diffused through the mass of people. Every parent in the State has a school placed in his neighbourhood; and every child is furnished with the means of the most necessary instruction. To aid, and to complete, these peculiar advantages, a church in every district of a moderate size, opens its doors to the surrounding inhabitants, and invites every family to receive the knowledge, communicated by the Word of God.

The same doctrine might be even more strongly illustrated, if the time would permit, from the deplorable contrast to the picture already drawn, presented by the desolations and miseries of vice and ignorance have in most instances prevailed without a mixture, and reigned without control. Rulers have trampled on the necks, rioted on the spoils, and sported with the miseries, of their subjects. Subjects have fallen before them with impious homage, and slavish brutism, or rescued themselves from oppression, to run mad with the frenzy of anarchy, and to wanton in plunder and blood. Nations, as if in love with misery, and unsatisfied to see their sufferings so small, have reached out an eager hand to grasp at woe. War has been the profession of man, and arms his instruments of business, and of pleasure. Conquest, like a roaring lion, has stalked round the desolated globe, seeking whom he might devour. In his trains, Ambition has smoked with slaughter; Avarice has ground the poor into dust; and Pollution, like the messenger of death to the army of Sennacherib, has changed the host of man into putrefied corpses. Fiends have looked on, and triumphed; Angels have wondered, and wept; and Heaven, as if discouraged from efforts, has given up its work to waste and destruction.

The end of the observations, which I have made, is to impress on the minds of this audience the importance of public and individual exertions to promote knowledge and virtue in this State. If the observations are just, the value of the object will not be disputed. But it is one thing to be convinced of the importance of an object, and another to feel it in such a manner, as to be roused into exertion in its behalf. Ignorance of the most proper methods of exertion, difficulties always presenting themselves in its progress, and doubts concerning its success, added to native indolence, easily damp the rising effort, and incline us to shift the burden from ourselves to others, and to rest satisfied with the general opiate of conscience, that our attempts will be vain, and may, therefore, be safely neglected.

To strengthen this enervating conclusion in our minds, we naturally summon to our aid the general voice of human experience. “The course of human affairs,” we easily say, and say with some degree of truth, “has been a constant exhibition of extreme difficulty, ever found in extending and establishing virtue in the present world. The volume of man is written only in black; and page after page, when carefully turned over, is seen to be marked only with lines of vice, ignorance, and sorrow. Centuries have rolled on, without a beam of light; and Continents, throughout their expanded regions, have reeked with the slaughter of man, and echoed to the voice of mourning and misery. Intervals have indeed appeared of a brighter aspect; and favoured tracts have, at times, enjoyed the twilight promise of approaching day. But how few have been these envied exceptions to the general character of time, and to the general state of the world! What miniatures of happiness, knowledge, and virtue must we oppose to the gigantic figures of war, and woe, of idolatry and brutism! A few years form the only contrast to sixty centuries; and Switzerland is that small dust of the balance, which must be weighed against Africa and Asia.”

Such is the language of sloth and discouragement. In the main it is true; but it is not the whole truth. The few experiments, which have been imperfectly made, to diffuse knowledge, and implant and cultivate virtue, in the mass of mankind, have sufficiently proved, that efforts for this end may be successful; and that, when man has prepared the ground, and sown the seed, Heaven will refuse neither the rain, nor the sunshine.

The whole cultivation of virtue is a conflict with vice; but the warfare is honourable, and the victory fruitful in advantage, beyond the reach of computation. Nothing valuable comes to man, without his cooperation; and the toil is commonly proportioned to the worth of the acquisition. As the diffusion of Virtue over a Community is the first social blessing, so it ought, according to the analogy of Providence, to be expected to demand greater efforts, than any other blessing. Liberty has often been the price of lives scarcely numerable, and of property exceeding calculation. Yet Liberty is a profession of less importance than Virtue. Had half he efforts been made to promote virtue, which have been made to extend war and slaughter, virtue would not, probably, constitute the prevailing human character. But Virtue, though the first good of man, has least engaged his attention.

Wherever exertions have been made for the extension of virtue, success has followed. Under the superintendence, and by the labours, of the Apostles, its progress was a greater miracle to the eye, than all those, which they performed, as means of its existence. With the gradual decay of effort it gradually ceased. At the Reformation, exertion rose to a character almost Apostolic, and success attended it, like that of the Apostles. In Switzerland, Holland, Scotland, England, and in some parts of the American States, the growth and prevalence of Virtue has, at times, and through a considerable period, been fully proportioned to the efforts in its behalf, and answered every rational hope. There is, therefore, from experience, no reason for discouragement.

It may, perhaps, be said, that Virtue is the gift of God. This is no objection to the sentiments, here advanced. It is their support. Every blessing is the gift of God. The harvest is as truly his gift, as Virtue. Nor is there a reason to believe, that he will less willingly meet, with his blessing, him, who labours to adorn the mind with moral beauty, and to plant in it the feeds of righteousness, than him, who, with equal industry, is employed in dressing the earth in verdure, and in filling the field with bread.

That knowledge may be effectually diffused through a Community will not be doubted.

On the methods, by which these great attributes of the mind, these great means of Social happiness, may be most effectually cultivated, and established, I have much to say; and feel it to be a misfortune, that so large a part of my time seemed necessary to prepare a foundation, when the whole was necessary to raise the structure. To the time, however, I must conform, and important as I deem the subject, must dismiss it with mere hints, and heads of discourse.

The Laws of every country have all, or may have, an important influence on this subject. The formation and establishment of knowledge and virtue in the citizens of a Community is the first business of Legislation, and will more easily and more effectually establish order, and secure liberty, than all the checks, balances, and penalties, which have been devised by man. With the Legislature this business should begin; and with reference to it most, if not all, their important measures ought to be concerted. They wish, doubtless, to do good to their country. In this way they can do more good to it, than in any other. Were this sentiment, in full strength, in the mind of every Legislator, the object could not fail of being accomplished.

In the exact execution of Law, those magistrates, to whom this duty is entrusted, may find an extensive field for the employment of this most honourable patriotism. It is not an uncommon, nor unfounded opinion, that the duties of executive officer are, here, less punctually performed, than the public good demands; and that too strong a spirit of accommodation is become their customary character. Little crimes appear, unhappily, to be passed over with inattention, and thus prepare the way for those which are greater. It is desirable, that no laws, beside necessary ones, should exist; but is equally and even more desirable, that every existing Law should be executed. In an effectual Grand-Jury this State is unhappily and singularly defective, and suffers daily from the defect. Until this evil shall be remedied, one wide door to immorality and unhappiness will be unnecessarily left open.

Calumny against the several Officers, employed in governmental duty, is one of the most obvious methods of weakening government. The esteem of the Community is, in all countries, an object of no small importance to persons in public agency; but, in this country, it is of the highest importance. The magistrate, here, is raised above others by his office only; and the esteem, which he wishes to obtain, is the esteem of his peers and companions. To deprive him of this esteem is to deprive him, in a sense, of his all; and to do it wantonly and maliciously is to act the part of an enemy, and a savage. “Thou shalt no speak evil of the ruler of thy people” is equally a law of Revelation, and of Common sense. If Rulers transgress, and act with fraud, or injustice, the path of regular impeachment is open, and ought to be pursued. Mere political slander is the result of ambition, or of malice; and is as mischievous in its effects, as base in its origin. The length, to which it has already proceeded, is great; the length, to which it will proceed, cannot be calculated. A small degree of foresight, will, however, enable us to decide, that, should it not be checked, the possession of office will, of itself, be esteemed, ere long, an adequate proof of dishonesty.

But as Public happiness depends, in this country, at least, on the personal character of its inhabitants at large, so the promotion of public happiness must, in a great measure, rest on personal exertions. Men of every description, who wish the end accomplished, must unite to furnish the means.

The primary mean of this end has, I flatter myself, been proved to be Virtue. States may be rich, powerful and free; and yet not be happy. Antiquity furnishes us with a long and pompous list of rich and powerful States; but scarcely with one, in which the great body of citizens in this State would not, if fairly informed in the history of those States, be wholly unwilling to live; life, in our view, being hardly worth possessing, if it must be passed in so wretched state of Society. The same observation, with nearly the same force, may be applied to almost all the present States of Europe. The Grisons, allies of the Switzers, are, by their Constitution of government, the freest people, perhaps, of any on the Eastern Continent. Still they are an unhappy people. They have neither virtue to desire, nor knowledge to understand, the common interest. Justice, suffrages, and the whole public weal, are, among them sold annually, like goods in the market. Hence, with the fullest possession of liberty, they are equally contemptible and wretched.

There are two great means of promoting virtue; Religious Education and Public Worship. Religious education prepares the mind to love, to attend, and to profit by public worship; and public worship supports and regulates religious education. Without public worship, children would cease to be religiously educated; and without religious education, public worship would cease to be attended.

To render public worship useful, it must be frequented; and, to make it frequented, it must, so far as consists with its nature, be made pleasing. For this purpose, the ministers of this worship must, so far as the circumstances of men will allow, be persons of knowledge, virtue and dignity. To secure, in any country, a succession of such ministers, their support ought to be comfortable; the source neither of splendor and luxury on the one hand, nor of suffering and meanness on the other. Opulent livings would invite, and would be filled by those, who most covet opulence; the aspiring, and the unprincipled. A bare living would be left to sloth, and ignorance. A rich and proud ministry would be inaccessible to the poor, and the humble; a ministry struggling under penury would tremble at the frowns of the rich, and the great. The support of ministers ought also to be secure, and endangered by nothing, but their misconduct. Precarious livings, beside their exposure to all the evils of scanty ones, would furnish, to the incumbents, daily temptations to sacrifice conscience and duty to the whims, and the vices, of those, from whose goodwill they hoped to derive their daily bread. No Youth, possessed of learning, dignity, and worth, can be expected to venture himself on the ocean of life, in a bark, which so evidently announces a speedy and certain shipwreck, by its total want of strength, and safety, for the voyage.

Religion is always estimated by the character of its ministers. If they are generally vile, the religion, which they profess, is generally abhorred; if contemptible, it is despised; but, if worthy and dignified, it cannot but be respected. Thus intimate and inseparable is the permanent and sufficient support of the ministers of religion with virtue, and of course with the existence, and the stability, of public happiness.

Religious education, in the first instance, is domestic. To the early mind, parents are the ministers of religion appointed by God himself, and invested by him with authority, and advantages, wholly peculiar. On that mind it is in their power to make impressions, of the highest importance, and the most benign efficacy; impressions, which extend to all the great concerns of man, which mould the whole future character, and which stand, thro’ life, as prominent features in the conduct of every day. “Even a child may be known by his goings,” says Solomon; or, as in the Hebrew, “By the goings of a Child may be know his future character, when a man.” In the earliest stages of childhood may be implanted such a sense of right and wrong, of truth and falsehood, of honesty and fraud, of good will and malice, of accountableness and judgment, of heaven and hell, of the glorious character of the Redeemer, of the presence, inspection, agency, and government, of God, as will remain, influence, and govern, through every succeeding period; such a sense, as will, in a great measure, form for every social duty, and preclude the necessity of most political restraints, and of all political violence. To communicate a religious education to their children is the greatest blessing, which parents can usually confer upon them; the highest service, which they can render to society; and the most important duty, which they can perform to God. Yet there is, perhaps, no duty more neglected.

To the efforts of parents those of Schoolmasters ought to be added. Where parents perform this duty, the Schoolmaster may happily increase, and rivet, the impression: where they neglect it, he may, in no small measure, supply the defect. Moral instruction of every kind ought invariably to form a material part of school education. To this end, it ought to be exacted of every Schoolmaster, that he be, in the public eye, a virtuous man.

For this, and every other purpose, which is expected from schools, it is necessary, that the legislature should steadily interfere. Private efforts may do much; but they cannot do all. Where the suffrages of all concerned are of equal influence, measures are merely the effect of compromise, and incapable of system, or regularity. Hence the absolute necessity of some superior control. Visitors, under Legislative authority, ought to be empowered, and obliged, to inspect the knowledge, and the morals, of the teachers, the system of education, the diligence with which it is pursued, and the progress of the pupils in knowledge, manners, and morals. Regular returns ought to be made to Commissioners of Government, concerning the whole state of education; and public benefits should invariably reward such persons, as originate essential improvements.

Example, Union, Concert, are primary wheels in every system of improvement. All things flourish, where all hearts are engaged. The great object, here urged, has never been, but very imperfectly, made a national object. It ought to be the first end of all measures national and personal. Power, wealth, and splendor, cannot be more certainly acquired. It is as easy to bless, as to conquer; to enrich a land with virtue, and to adorn it with knowledge, as to store it with silver, and load it with villas and palaces. Man may as easily be a Saint, as a Savage; and Nations as easily enlightened with Millennial glory, as overcast with the midnight of Gothicism. All that is necessary, on the part of man, is to bring the subject home to his heart, to feel its inestimable importance, to realize its practicability, and to make it the chief aim of his fixed endeavours.

Confident of the justice, and of the interesting nature, of these observations, let me ask, is there in the wider regions of the universe, an object, which ought more to engross the attention, and the labour, of man? Is there a more honourable patriotism, or a truer friendship to liberty, than thus to aim, and thus to labour? Ought it not to seize the heart, to inspire the voice, and to command the hands, of every citizen? Who can say, “My labours will be useless”? Who is so poor, so lowly, so ignorant, as not to be able to cast in to the public stock []? Who among the richer, the more enlightened, the more dignified, can, to any other purpose, so nobly contribute, of his abundance?

Connecticut can never be distinguished for extent of territory, superior wealth, or great numbers of inhabitants. This, instead of being a misfortune, ought to be esteemed a blessing. A nobler distinction is thrown by a good Providence into its hands. It may rise to pre-eminence in knowledge, virtue, and happiness. We need not grudge the dross, while the gold is ours. It may be the Athens, not of a savage, idolatrous, and brutal world, but of a world enlightened, refined, and Christian. Let its citizens unite in well concerted and determined efforts, for this end; and it will be accomplished.

How honourable, how enviable a task, how glorious a crown of patriotic labours already undergone, would it be to the officers of an Army, distinguished by unprecedented and most public-spirited efforts, in the cause of their country, to stand foremost in the pursuit of this first interest, this supreme glory, of that country? With that courage with which they braved a foreign invader, that patience of suffering with which they encountered toil, and want, and that perseverance with which they surmounted difficulty and discouragement, to meet every foe employed to attack, every art exerted to undermine, and every obstacle raised up to hinder, our public prosperity? What a wreath of laurel will be twined around their memory, whenever it is rehearsed, that they were, alike, the best soldiers, and the best citizens? The path to this glory, I flatter myself, I have disclosed.

Such efforts are visibly demanded of all citizens to preserve, as well as to increase, the happiness, for which that Army so bravely fought, and so largely bled. Our very Government, so mild, so useful, and so harmoniously adopted, has been attacked by intrigue, calumny, and insurrection. This evil has existed, while the chair of Magistracy has been filled by a [] has probably wrought for this country [] than were ever wrought by any man for any country: whose wisdom has proved superior to every perplexity, whose patriotism to every temptation, and whose fortitude to every trial: a Man, who can pass through no American States, survey no field, and tread on no spot of ground, which he has not saved from devastation; who can mix with no assembly, visit no family, and accost no person, who must not say, “Our freedom, our peace, our safety, we owe first to God, and next to you:” who can turn his ear to no sound of joy, which he has not a share in exciting; and open his eye on no scene of comfort, which does not trace him as its origin; a man to whom poets, orators, sages, legislators, and the nations of two worlds, have eagerly paid their tribute of esteem, admiration, and love. Against this very man have these evils been directed. What they must be looked for, when the same seat shall be filled by inferior talents, sustained by a patriotism less unequivocal, and sanctioned by a popularity less complete? What, but an event, at which philanthropy shudders; and, with the existence of which, the hopes of the wise, and the good, will be extinguished forever? To avert such a catastrophe, and under the banner of such a leader, his illustrious companions in the field will cheerfully unite, and call to the standard every virtuous citizen, every friend of man, to preserve all that, for which they fought, and to increase all that, in which they glory. Thus will they secure the peace of an approving conscience, enjoy the transports of an expanded benevolence, and commence a career of honour which will know no end.

The Rev. Nathan Strong (1748-1816) was born in Connecticut. He attended Yale, graduating in 1769 (he went on to receive a D.D. degree from Princeton in 1801). Rev. Strong was set in as pastor of the First Church of Hartford in 1774. Interestingly, both his father, also named Nathan, and brother, Joseph, were clergymen as well. Strong became a chaplain in the patriot army during the American Revolution, and was a strong supporter of the American cause. He later was a chief founder and a manager of the Connecticut Missionary Society (founded in 1798), and was involved in the ” Connecticut Evangelical Magazine,” which lasted fifteen years. In this “execution sermon,” preached before Richard Doane was executed for the murder of Daniel M’Iver, Rev. Strong reminds his listeners (including Doane) of the terrible consequences of a sinful life apart from God, and urges them to be reconciled to God through Christ.

The Rev. Nathan Strong (1748-1816) was born in Connecticut. He attended Yale, graduating in 1769 (he went on to receive a D.D. degree from Princeton in 1801). Rev. Strong was set in as pastor of the First Church of Hartford in 1774. Interestingly, both his father, also named Nathan, and brother, Joseph, were clergymen as well. Strong became a chaplain in the patriot army during the American Revolution, and was a strong supporter of the American cause. He later was a chief founder and a manager of the Connecticut Missionary Society (founded in 1798), and was involved in the ” Connecticut Evangelical Magazine,” which lasted fifteen years. In this “execution sermon,” preached before Richard Doane was executed for the murder of Daniel M’Iver, Rev. Strong reminds his listeners (including Doane) of the terrible consequences of a sinful life apart from God, and urges them to be reconciled to God through Christ.

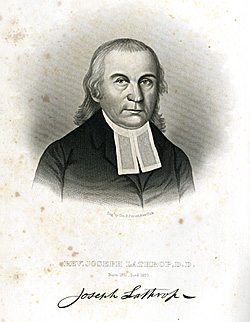

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.