No, Revisionists, Thanksgiving is not

a Day of Mourning

by David Barton

Just before Thanksgiving [2017], I discussed the origins of the holiday on Glenn Beck’s show The Vault.[1] I understand the program has been used profitably by teachers throughout America. After a college professor showed the episode to a class, a student sent him eleven “articles” posted on the internet purporting to show that the Pilgrims killed and oppressed Indians. He asked me how I would respond to the posts, and what resources I would recommend for readers interested in an accurate account of the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving. I’m happy to be of assistance.

The internet posts did indeed claim that the Pilgrims killed and oppressed Indians.[2] However, they were all opinion pieces that contained no footnotes and mentioned only a few sources—none of which were published before 1990.

If one is seeking to establish facts – such as those related to the Pilgrims’ longstanding peace with the Indians from 1621–1675 – it is necessary to consult primary sources from that era, which include journals, diaries, letters, recorded speeches, and other first-hand evidence about those events. Sources should always be properly cited so that interested, or skeptical, readers can examine them.

The opinion pieces cited by the student made broad, sweeping claims and lacked specificity or details about where or when Pilgrims killed and oppressed Indians. Some articles referenced the Indian war of 1637, but some of the claims could have also referred to an encounter in 1623, or King Philip’s War of 1675, the three early conflicts between Indians and the Pilgrims.

To confirm the truth about any such claims and incidents, three excellent primary sources about the Pilgrims should be consulted. First, Of Plymouth Plantation by William Bradford. (Bradford regularly served as governor of the colony from 1622–1656, and his journals cover the years 1620–1647). Second, A Relation or Journal of the Beginning and Proceedings of the English Plantation Settled at Plimoth in New England (also known as Mourt’s Relation, written by Pilgrims William Bradford and Edward Winslow, covering 1620–1621, including the Pilgrims’ relations with the Indians). And third, Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers of the Colony of Plymouth, from 1602 to 1625 (1841; Alexander Young, editor, it includes records of the Pilgrims compiled from 1602–1625).

And there are some excellent contemporary works based on these earlier sources, including Robert Bartlett’s The Pilgrim Way (1971), George Willison’s Saints and Strangers (1965), and anything written about the Pilgrims by Dr. Jeremy Bangs, former Chief Curator of Plimoth Plantation, in Plymouth, Massachusetts (the original home of the Pilgrims) and director of the Leiden-American Pilgrim Museum Foundation. Bangs is considered by other colonial historians to be one the best modern experts on the Pilgrims. He has authored multiple books and articles about the Pilgrims and Puritans, including the easily accessible piece “The Truth About Thanksgiving Is that the Debunkers are Wrong” (available at: https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/15002).

Older works also provide an historically accurate view of the Pilgrims and their many contributions. Particularly useful are American history books written by nineteenth-century historians George Bancroft, Benson Lossing, and Charles Coffin. (These books are available online at www.books.google.com.)

Also of benefit is the long series of Forefathers’ Day orations. Since 1769, Forefathers’ Day has been celebrated annually in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to commemorate the landing of the Pilgrims. The celebration includes annual orations about the Pilgrims that, collectively, provide much history and perspective. Among those delivering these orations were many famous individuals (links to their particular oration appear in each footnote):

· An Oration Delivered at Plymouth, December 22, 1802, At the Anniversary Commemoration of the First Landing of Our Ancestors At That Place, by John Quincy Adams[3]

· A Discourse Delivered at Plymouth, December 22, 1820, In Commemoration of the First Settlement of New-England, by Daniel Webster[4]

· Others orators addressing the subject of the Pilgrims in these annual commemorations include Edward Everett (President of Harvard, Governor of Massachusetts, US Senator);[5] Robert C. Winthrop (President of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Speaker of the US House of Representatives);[6] Rufus Choate (US Senator);[7] Oliver Wendell Holmes (Professor at Harvard, physician, writer);[8] Lyman Beecher (abolitionist; President of Lane Seminary);[9] a second speech by Daniel Webster (US Senator, Secretary of State to three presidents);[10] and others.

(The following link contains a listing of these addresses delivered from 1770 to 1865: www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44539521.pdf.)

Of the three major conflicts between the Pilgrims and the Indians, King Philip’s War was by far the biggest. Concerning this, there are many reputable academic or historical society websites that present a neutral, factual view, including:

· https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/king_philip.htm

· https://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars16011800/p/King-Philips-War-1675-1676.htm

· https://colonialwarsct.org/1675.htm

While these websites are good for brief and general overviews, we always encourage readers to consult primary sources, and particularly important for the 1675 King Philip’s War are:

· A Relation of the Indian War, by Mr. Easton, of Rhode Island, by John Easton, 1675[11]

· A Narrative of the Indian Wars in New-England, From the First Planting Thereof, in the Year 1607, to the Year 1677, by the Rev. William Hubbard, 1677[12]

· The Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, 1682[13]

· Cotton Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana, or The Ecclesiastical History of New-England, 1702 (2 vols.)[14]

The following three books are secondary sources about that war, but they rely heavily on relevant primary sources. We therefore highly recommend them:

· The History of King Philip’s War, by Samuel G. Drake, 1825[15] (an expansion of A Brief History of the Warr with the Indians in New-England, by Increase Mather, 1676[16])

· The History of King Philip’s War, by Benjamin Church, 1865 (based on the writings of those who participated in the war)[17]

· King Philip’s War, Based on the Records and Archives of Massachusetts, Plymouth, and Rhode Island and Connecticut, and Contemporary Letters and Accounts, by George Ellis and John Morris of the Connecticut Historical Society, 1906[18]

— — — ⧫ ⧫ ⧫ — — —

After receiving the inquiry from the professor and looking over the articles provided by the student, we began examining the primary source works mentioned above. We also contacted historians in Massachusetts, including those who help run the Pilgrim museum. The outcome was the same. State historians affirm that the official peace between the Pilgrims and the Indians was the longest on record—they have found no record of any treaty that lasted longer than the 54 years of the Pilgrim treaty (1621–1675). Furthermore, when the treaty was eventually broken in 1675 during King Philip’s War, it was the Indians and not the Pilgrims who violated it.

Here is a brief overview (based on primary sources, referenced in the footnotes) verifying what led up to that conflict and the breaking of the treaty.

The Pilgrims, after arriving in December 1620, survived a difficult beginning with the help of several Indians who befriended them.[19] Intending to live in the area where they had landed, they approached the local tribe, seeking to purchase land. The price was set by the Indians, and written documentation of sale was received for those purchased lands.[20]

This policy of purchasing land from the Indians came to characterize the general practice of the New England and portions of the mid-Atlantic regions, being mirrored not only by the Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony[21] but also by the Rev. Roger Williams with Rhode Island,[22] the Rev. Thomas Hooker with Connecticut,[23] and William Penn with Pennsylvania.[24] (On one occasion, Penn actually purchased some of the same tracts multiple times because at least three tribes claimed the same land, having taken and retaken it from each other in conquest; so Penn secured it from each.[25]) The practice of purchasing land from the Indians was also followed in New Hampshire,[26] New Jersey,[27] and New York.[28]

The Pilgrims and their Indian neighbors the Wampanoag entered into a peace treaty in 1621. Experiencing good relations with the tribe and a strong friendship with their chief, Massasoit, in 1623 he informed the Pilgrims of a treacherous assault to be made against them by the Massachusetts tribe, which was gathering other chiefs for a surprise attack.[29] Facing potential extermination, Pilgrim Miles Standish led a preemptive strike, thus saving the colonists. Without this, the Pilgrim story could have been as short-lived as that of the colonists of Roanoke, Virginia or Popham, Maine. Good relations continued between the Pilgrims and Wampanoag, with the next period of tensions with other tribes occurring in the 1637 Pequot War.

The Pequot were warlike and aggressive, even against their Indian neighbors on every side, which included the Wampanoag (allies and friends of the Pilgrims), Narragansett, Algonquian, and Mohegan. The Pequot had established a trading monopoly with the Dutch, which the arrival of the English threatened, so they determined to rid the region of the English. After killing some English settlers, the colonists responded and organized strikes against the Pequot.[30] The war spread across much of Connecticut, and also threatened the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies. The conflict ended when Sassacus, the chief of the Pequot, was pursued and killed by the Mohegan and Mohawks.[31]

One of the aforementioned articles provided by the student claimed that it was during this war that Pilgrims killed Indians,[32] but this claim is wrong. The Pilgrims’ participation in this conflict was limited to a skirmish at Manisses Villages, where no Indians were killed.[33] Some of the articles provided by the student claim that the Thanksgiving of 1637 was to give thanks that Indians were killed,[34] but this is also in error. It was called to give thanks for the end of the Pequot War.[35]

The Pilgrims lived in harmony with the Wampanoags from the time of their 1621 treaty, through the 1623 and 1637 conflicts, and until the long peace finally collapsed in 1675 with King Philip’s War. Today, revisionist scholars such as James D. Drake, Daniel R. Mandell, and Jill Lepore claim that this conflict was the result of Indians pushing back against greedy land-grabbing colonists, with the Indians simply trying to regain territory that was rightfully theirs.[36]

But such a portrayal is wrong. For example, Pilgrim Governor Josiah Winslow avowed that at the outbreak of the war:

I think I can clearly say that before these present troubles broke out, the English did not possess one foot of land in this colony but what was fairly obtained by honest purchase of the Indian proprietors.[37]

If King Philip’s War was not retaliation for the unjust seizing of Indian land by colonists, what was its cause? The answer is simple: Christian missionaries. Metacom—chief of the Wampanoag Indians and grandson of Massasoit, who took the English name King Philip —recognized that missionaries were converting Indians to Christianity, which was changing some behaviors. This threatened their traditional way of life.

Prior to becoming Christians, Indians often engaged in immoral practices such as the prolonged barbarous torture of captives.[38] Missionaries sought to end such practices by converting Indians and teaching them Christian morals.[39] Missionaries, including John Eliot, Thomas Mayhew, and Andrew White worked extensively with various tribes and had great success in converting Indians to Christianity. By 1674, Eliot’s Christian villages of “praying Indians” in Massachusetts numbered as many as 3,600 converts.[40] It was in the following year (1675) that Metacom, fearing that Christianity would change Indian culture,[41] launched ferocious surprise assaults against settlers in the region,[42] seeking to exterminate all English colonists in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts.

Numerous places in New England were suddenly and unexpectedly attacked. Colonists were murdered and their belongings burned or destroyed.[43] This included even the town of Providence, where Roger William’s own home was burned.[44] Significantly, Williams had always been on the best of terms with the Indians, not only having purchased his colony from them[45] but also having championed Indian rights and claims.[46] Yet, regardless of how well Christian settlers had previously treated Indians, Christians were all to be exterminated; their very existence was perceived as a threat to Indian practices.

King Philip’s War cannot be accurately characterized as Indians versus the English, however, for many of those attacked were themselves Indians—but they were Christian Indians. They, like the settlers, were targeted, hurt, or killed by their unconverted brethren.[47] To secure their own lives and safety, many of the converted Indians fought side-by-side with the colonists throughout the conflict,[48] and the war eventually ended when Metacom was killed by another Indian.[49]

Returning to the objections raised by the student, it is true that Pilgrims and Puritans killed Indians—but in the context of a just and defensive war. The war lasted about fifteen months, and early in the war more settlers died than did Indians—largely because of the surprise attacks. In fact, of the ninety towns in Massachusetts and Plymouth Colony, twelve were totally destroyed and forty more attacked and partially destroyed.[50] But eventually the colonists assembled local militias and fought back in an organized fashion, finally gaining the upper hand. By the conclusion of the war, 600 settlers and 3,000 Indians had been killed—the highest casualty rate by percentage of total population of any war in American history.[51]

This information about King Philip’s War is not to suggest that the amount of land owned by Indians was not decreasing; it was. But the diminishing land holdings in this region during this time was definitely not for the reason we are often told today. Indian land was fairly purchased by settlers, not stolen.[52] Early historian George Bancroft (1800-1891), known as “The Father of American History”[53] for his systematic approach to documenting the story of America, confirmed that Indian lands were indeed shrinking because the Indians’ own “repeated sales of land has narrowed their domains” to the point where “they found themselves deprived of their broad acres, and by their own legal contracts driven, as it were, into the sea”[54] (emphasis added).

This is not to say that land was never stolen from Indians. Some definitely was. For instance, during the heyday of westward expansion that began in the early nineteenth century, the Indian removal policies of Andrew Jackson certainly violated private property rights,[55] and such policies became the rule rather than the exception, forcibly driving Indians from their lands in Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, and elsewhere across the Southeast. By 1845, the term “Manifest Destiny” was coined to describe the growing notion that it was America’s “destiny” to spread westward, and that nothing—including Indians—should be allowed to stand in the way. As a result, the Biblical view of purchasing private property from its owner was replaced with the anti-Biblical notion that “possession was nine-tenths of the law” and therefore whoever could take and hold the land was its “rightful” owner.[56]

The 19th century deterioration in relations between Americans and Indians over unjust land seizures occurred most commonly two centuries after the Pilgrims. The original treaty the Pilgrims negotiated with the Indians lasted for 54 years until the Indians broke it; and in general, the Pilgrim and Puritan killings of Indians occurred in their own self-defense primarily against the perfidious unprovoked attacks from Metacom’s Indians, and then in ending the war he had started. We find no historical basis to support the general claim made in the articles provided by the student, and certainly no evidence to support the overall tone of the claims in those internet posts.

Endnotes

[19] For example, Samaset and Squanto are both mentioned in William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation (Boston: 1856), pp. 93-95; Squanto is called Tisquantum in Mourt’s Relation or Journal of the Planation at Plymouth (Boston: John Kimball Wiggin, 1865), pp. 102, 106. Mourt’s Relation also mentions Hobamak (also known as Hobbamock), p. 123.

[20] James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth, from its First Settlement in 1620 to the Present Time (Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1835), p. 138.

[21] George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1848), Vol. I, pp. 350-351.

[22] William Gammell, Makers of American History: Roger Williams (New York: The University Society, 1904), pp. 61-62.

[23] G. H. Hollister, The History of Connecticut, From the First Settlement of the Colony to the Adoption of the Present Constitution (New Haven: Durrie & Peck, 1855), pp. 18-19, 96.

[24] Samuel M. Janney, The Life of William Penn: With Selections from His Correspondence and Autobiography (Philadelphia: Friends Book Association, 1882), pp. 121-122, 442; George Bancroft, History of the United States of America (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1848), Vol. II, pp. 381-382.

[25] Samuel M. Janney, The Life of William Penn: With Selections from His Correspondence and Autobiography (Philadelphia: Friends Book Association, 1882), p. 442: “It appears that Penn, before his return to England in 1684, had taken measures to purchase the lands on the Susquehanna from the Five Nations (Iroquois) who claimed a right to them by conquest…Governor Dongan, having made the purchase, conveyed the same to William Penn, by deed dated January 13, 1696, in consideration of 100 [pounds] sterling. The Susquehanna Indians did not recognize the right of the Five Nations to make this sale; and, in order to satisfy their demands, Penn entered into a treaty with two of their chiefs, named Widnpah and Andaggy Innekquagh, whose deed, dated September 13th, 1700, conveys the same lands and confirms the bargain and sale made to Governor Dongan. But it appears there was still another chief claiming an interest in those lands, viz. Connoodaghoh, king of the Conostoga or Minquary Indians. This sachem, on company with the king of the Shawnese, the chief of the Ganawese, inhabiting at the heads of the Potomac, the brother of the emperor of great king of the Onondagoes, Indian Harvey, their interpreter, with others of the their tribes to the number of forty, met Penn and his council in Philadelphia on the 23d of 2d month, (April) 1701, and entered into a treaty of amity, in which they also confirmed the sale of the lands on the Susquehanna.”

[26] Jeremy Belknap, The History of New Hampshire (Dover, NH: J. Mann & JK Remick, 1812), pp. 16-17.

[27] John Warner Barber, The History and Antiquities of New England, New York and New Jersey (Worcester: Dorr & Howland & Co, 1841), p. 66.

[28] W. H. Carpenter and T. S. Arthur, History of New Jersey (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1853), pp. 25, 27-28.

[29] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation (Boston: 1856), p. 131.

[30] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation (Boston: 1856), pp. 351-342, 356-357. 131.

[31] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation (Boston: 1856), pp. 349-361; The History of New England from 1630 to 1649 by John Winthrop, James Savage, editor (Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1825), Vol. I, pp. 222-226.

[33] For an account of the non-involvement of the Pilgrims in the 1837 Pequot War, see: William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation (Boston: 1856), pp. 355-356, “The Court here agreed forthwith to send 50 men at their own charge; and with as much speed as possible they could, got them armed, and had made them ready under sufficient leaders, and provide a bark to carry them provisions & tend upon them for all occasions; but when they were ready to march (with a supply from the Bay) they had word to stay, for the enemy was as good as vanquished, and there would be no need”; The History of New England from 1630 to 1649 by John Winthrop, James Savage, editor (Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1825), Vol. I, p. 226: “Upon our governor’s letter to Plymouth, our friends there agreed to send a pinnace, with forty men, to assist in the war against the Pequods; but they could not be ready to meet us at the first.”

[35] The History of New England from 1630 to 1649 by John Winthrop, James Savage, editor (Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1825), Vol. I, p. 226, entry for March 15, 1637: “There was a day of thanksgiving kept in all the churches for the victory obtained against the Pequods, and for other mercies.”

[36] James D. Drake, King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England 1675-1676 (MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), pp. 1, 30-31; Daniel R. Mandell, King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty (MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), pp. 27, 30; Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (Random House, 2009), “What’s in a Name?” More reputable writers have made similar claims. See, for example, Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America; Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975), pp. 128, 144-145; New England Encounters: Indians and Euroamericans ca. 1600-1850. Essays Drawn from The New England Quarterly, Alden T. Vaughan, editor (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999), pp. 61-64, David Bushnell, “The Treatment of the Indians in Plymouth Colony”; Karen Ordahal Kupperman, Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2000), p. 239.

[37] James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth, from its First Settlement in 1620 to the Present Time (Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1835), p. 138; Abiel Holmes, The Annals of America from the Discovery by Columbus in the Year 1492, to the Year 1826 (Cambridge: Hilliard & Brown, 1829), p. 383.

[38] See, for example, accounts such as:

· Franklin B. Hough, A Narrative of the Causes which Led to Philip’s Indian War, of 1675 and 1676, by John Easton of Rhode Island (Albany, NY: J. Munsell, 1863), pp. 143-144, an eyewitness account dated February 25, 1675: “Thomas Warner one of the two that came down from Albany and had been prisoner with the Indians who arrived here this morn, being examined, faith, that he was one of the persons that begin sent out from Hatfield where the English Army lay, to discover the enemy, but a party of Indians waylaid them, and shot down 5 of their company, and took 3 of which he and his comrade are two, the 3rd they put to death, the 9th was an Indian that came with them and escaped away. That the Indians lay still two days after they were taken, and then a party of about 30 with whom he was marched to a river to the north-east from thence about 80 miles called Oasuck, where about a fortnight after the rest of the army came to them, having in the mean time burnt two towns: they killed one of the prisoners presently after they had taken him, cutting a hole below his breast out of which they pulled his guts, and then cut off his head. That they put him so to death in the presence of him and his comrade, and threated them also with the like. That they burnt his nails, and put his feet to scald them against the fire, and drove a stake through one of his feet to pin him to the ground. The stake about the bigness of his finger, this was about 2 days after he was taken.”

· John S. C. Abbott, The History of King Philip (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1857), pp. 317-318, where Abbott, using the words of Cotton Mather, describes Indian tortures: “They stripped these unhappy prisoners, and caused them to run the gauntlet, and whipped them after a cruel and bloody manner. They then threw hot ashes upon them, and, cutting off collops of their flesh, they put fire into their wounds, and so, with exquisite, leisurely, horrible torments, roasted them out of the world.”

· Richard Markham, A Narrative History of King Philip’s War and the Indian Troubles in New England (New York: Dodd, Mean & Company, 1883), pp. 241-242, describing an event at the beginning of King Philip’s War: “A little after the middle of April [1676] Sudbury was attacked…Captain Wadsworth with fifty men had been dispatched from Boston that day to strengthen the garrison at Marlborough. After his company reached Marlborough, more than a score of miles from Boston, they learned that the savages were on their way against Sudbury…A small party of Indians encountered them when about a mile from their destination, and withstood them for a short time, but yielding to their superior numbers retreated into the forest. Wadsworth and his men followed, but when they were well into the woods suddenly found themselves the centre of five hundred yelling demons, who attacked them on all sides. They made their way to the top of a hill close at hand, and for four hours fought resolutely, losing but five men, for the savages had suffered severely in the first hand-to-hand attack, and feared to come to close quarters. As night came on the enemy set fire to the woods to the windward of their position. The leaves were dry as tinder, and a strong wind was blowing. The flames and smoke rolled up upon the devoted band, threatening their instant destruction. Stifled and scorched, they were forced to leave the hill in disorder. The Indians came upon them so like so many tigers, and outnumbering them ten to one in the confusion slew nearly all. Wadsworth himself was slain. Some few were taken prisoners, and that night were made to run the gauntlet, and after that were put to death by torture.”

[39] See, for example, J. W. Barber, United States Book; Or, Interesting Events in the History of the United States (New Haven: L. H. Young, 1834), p. 53; and Methodist Quarterly Review: 1858, D. D. Whedon, editor (New York: Carlton & Porter, 1858), Vol. XL, pp. 244-245: “In a short time, under the labors of Eliot, hundreds of Indians renounced their heathenism and embraced Christianity. As early as 1660 he had gathered ten settlements of Indians, who were comparatively civilized, and under religious influence…In 1675 King Philip’s War broke out. The missionary settlements of Eliot were in the center of the theater of this war. Many of the Christian Indians would have remained neutral; but Philip attacked them, and drove them into hostility; the commotions that followed not only prevented the progress of the Gospel, but destroyed much that had been done. War blasted all these opening religious prospects of the poor Indians; and war provoked, too, by the aggressions of the white man.”

[40] Gustav Warneck, Outline of a History of Protestant Mission from the Reformation to the Present Time (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1903), p. 165.

[41] J. W. Barber, United States Book; Or, Interesting Events in the History of the United States (New Haven: L. H. Young, 1834), p. 53n; John S. C. Abbott, The History of King Philip (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1857), pp. 171-172.

[42] J. W. Barber, United States Book; Or, Interesting Events in the History of the United States (New Haven: L. H. Young, 1834), pp. 53-54; Richard Markham, A Narrative History of King Philip’s War and the Indian Troubles in New England (New York: Dodd, Mean & Company, 1883), pp. 109-110.

[43] Franklin B. Hough, A Narrative of the Causes which Led to Philip’s Indian War, of 1675 and 1676, by John Easton of Rhode Island (Albany, NY: J. Munsell, 1863), p. 42, a letter dated June 29, 1675, pp. 176-177, “Record of a Court Martial, Held at Newport, R.I. in August, 1676, for the Trial of Indians charged with begin engaged in Philip’s Designs”; William Hubbard, A Narrative of the Indian Wars in New-England from the First Planting Thereof, in the Year 1607, to the Year 1677 (Danbury: Stiles Nichols, 1803), p. 64, notes from a meeting of the commissioners of the united colonies held at Boston, Sept. 9, 1675, pp. 77-78.

[44] National Park Service, “Frequently Asked Questions,” Roger Williams National Memorial Rhode Island (at: https://www.nps.gov/rowi/faqs.htm) (accessed on January 9, 2017). See also Welcome Arnold Greene, The Providence Plantations for Two Hundred and Fifty Years. An Historical Review of the Foundation, Rise, and Progress of the City of Providence (Providence, RI: J.A & R.A. Reid, 1886), p. 42.

[45] William Gammell, Makers of American History: Roger Williams (New York: The University Society, 1904), pp. 61-62.

[46] Romeo Elton, Life of Roger Williams (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1852), pp. 21, 33-34, 39-41, 44-45.

[47] Methodist Quarterly Review: 1858, D. D. Whedon, editor (New York: Carlton & Porter, 1858), Vol. XL, pp. 244-245; John S. C. Abbott, The History of King Philip (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1857), pp. 187-190, 216.

See, for example, Rev. John Holmes, Historical Sketches of the Missions of the United Brethren, p. 210, “With a view to execute their horrid purpose, the young Indians got together, chose the most ferocious to be their leaders, deposed all the old Chiefs, and guarded the whole Indian assembly, as if they were prisoners of war, especially the aged of both sexes. The venerable old Chief Tettepachsit was the first whom, they accused of possession poison, and having destroyed many Indians by his art. When the poor old man would not confess, they fastened with cords to two posts, and began to roast him at a slow fire.”; pp. 210-211, “During this torture, he [Chief Tettepachsit] said, that he kept poison in the house of our Indian brother Joshua. Nothing was more welcome to the savages than this accusation, for they wished to deprive us of the assistance of this man, who was the only Christian Indian residing with us at that time….We knew nothing of these horrible events, until the evening of the 16th, when a message was brought, that the savages had burned an old woman to death, who had been baptized by the Brethren in former times, and also that our poor Joshua was kept close prisoner.”; p. 139, “Their external troubles, however, did not yet terminate. They had not only a kind of tax imposed upon them, to show their dependence on the Iroquois , but the following very singular message was sent them: “The great head, i.e. the Council in Onondago, speak the truth and lie not: they rejoice that some of the believing Indians have moved to Wayomik, but now they lift up the remaining Mahikans and Delawares, and set them down also in Wayomik; for there a fire is kindled for them, and there they may plant and think on God: but if they will not hear, the great head will come and clean their ears with a red-hot iron (meaning they would set their houses on fire) and shoot them through the head with musquet-balls.”

[48] Increase Mather, The History of King Philip’s War (Albany: J. Munsell, 1862), pp. 49-50, 127-128, 184; Henry William Elson, History of the United States of America (The MacMillan Company, New York, 1904), p. 122; George Madison Bodge, Soldiers in King Philip’s War (Boston: 1906), pp. 34, 37, 104.

[49] John S. C. Abbott, The History of King Philip (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1857), p. 361.

[50] John Fiske, The Beginnings of New England (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company,, 1890), p. 240.

[51] James David Drake, King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 1675-1676 (The University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), pp. 1–15.

[52] See, for example, George Bancroft, History of the United States From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1848), Vol. II, p. 99.

[54] George Bancroft, History of the United States From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1848), Vol. II, p. 99.

[55] William Garrott Brown, Andrew Jackson (New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1900), pp. 130-131; William Graham Sumner, American Statesmen: Andrew Jackson (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1899), pp. 224-229.

[56] See, for example, the Cherokee nation in Georgia. Georgia passed laws dividing Cherokee land up in various counties and put those lands in control of the state. Andrew Jackson, the president at that time, did not interfere with the Georgia laws and would not enforce or support the Supreme Court’s decision that declared this Georgia law unconstitutional. William Garrott Brown, Andrew Jackson (New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1900), pp. 130-131.

* Originally published: Feb. 23, 2017.

* This article concerns a historical issue and may not have updated information.

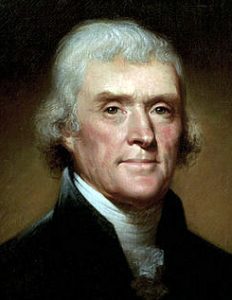

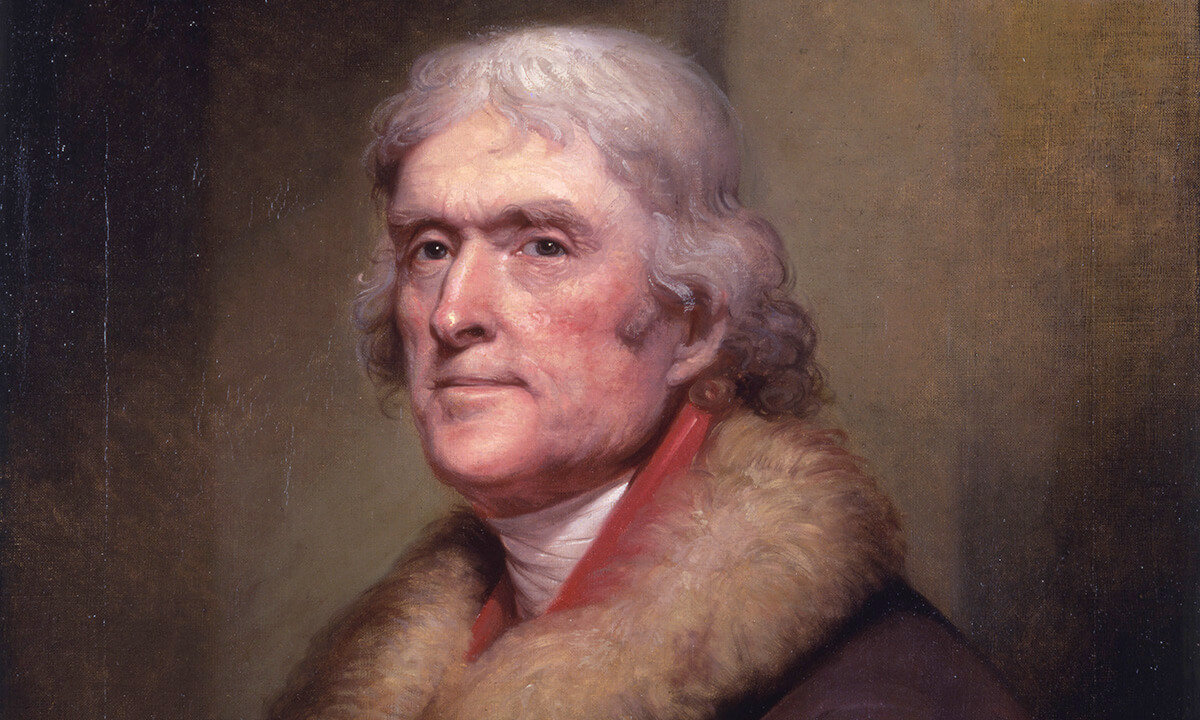

In fact, a young Daniel Webster recounted a conversation he had with an elderly Thomas Jefferson on this point. Jefferson told him:

In fact, a young Daniel Webster recounted a conversation he had with an elderly Thomas Jefferson on this point. Jefferson told him:The education of our children is never out of my mind. Train them to virtue. Habituate them to industry, activity and spirit. Make them consider every vice as shameful and unmanly. Fire them with ambition to be useful. Make them disdain to be destitute of any useful or ornamental knowledge or accomplishment. Fix their ambition upon great and solid objects, and their contempt upon little, frivolous and useless ones.

I advise you, my son, in whatever you read, and most of all in reading the Bible, to remember that it is for the purpose of making you wiser and more virtuous. I have myself, for many years, made it a practice to read through the Bible once every year. I have always endeavored to read it with the same spirit and temper of mind, which I now recommend to you: that is, with the intention and desire that it may contribute to my advancement in wisdom and virtue.

I was much mortified to find the whole force of this man’s vain genius pointed at the youth of America….This awful consequence created some alarm in my mind lest at any future day you, my beloved child, might take up this plausible address of infidelity….I have endeavored to…show his extreme ignorance of the Divine Scriptures…not knowing that “they are the power of God unto salvation, to everyone that believeth” [Romans 1:16].

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city Hancock and Adams were staying in the home of Lexington Pastor Jonas Clark.

Hancock and Adams were staying in the home of Lexington Pastor Jonas Clark.

On April 6, 1917, the US entered World War I,

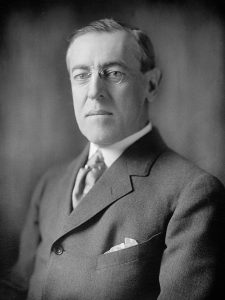

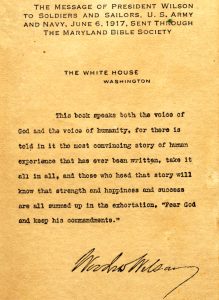

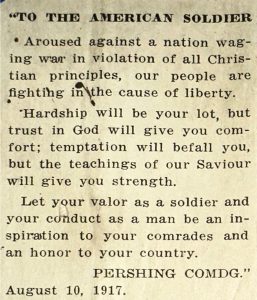

On April 6, 1917, the US entered World War I, Also, throughout American history, Bibles have been distributed to soldiers going into war and sometimes these Bibles would include messages from leaders on the importance of Bible reading. For example, a letter from President Woodrow Wilson was used in a WWI era Bible (pictured here from a Bible in WallBuilders’ Collection):

Also, throughout American history, Bibles have been distributed to soldiers going into war and sometimes these Bibles would include messages from leaders on the importance of Bible reading. For example, a letter from President Woodrow Wilson was used in a WWI era Bible (pictured here from a Bible in WallBuilders’ Collection): To The American Soldier:

To The American Soldier:

Easter is celebrated across the world as one of the most significant Christian holy days — as a time when we pause to remember the great sacrifice of Jesus on the cross as well as the ultimate triumph of His resurrection. America’s Founding Fathers often commented on Easter.

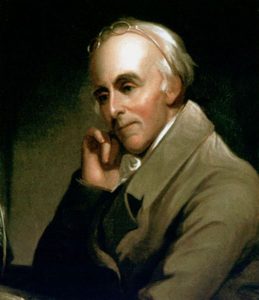

Easter is celebrated across the world as one of the most significant Christian holy days — as a time when we pause to remember the great sacrifice of Jesus on the cross as well as the ultimate triumph of His resurrection. America’s Founding Fathers often commented on Easter. The approaching festival of Easter, and the merits and mercies of our Redeemer copiosa assudeum redemptio [with the Lord there is plentiful redemption] have lead me into this chain of meditation and reasoning, and have inspired me with the hope of finding mercy before my Judge, and of being happy in the life to come — a happiness I wish you to participate with me by infusing into your heart a similar hope.

The approaching festival of Easter, and the merits and mercies of our Redeemer copiosa assudeum redemptio [with the Lord there is plentiful redemption] have lead me into this chain of meditation and reasoning, and have inspired me with the hope of finding mercy before my Judge, and of being happy in the life to come — a happiness I wish you to participate with me by infusing into your heart a similar hope. He forgave the crime of murder on His cross; and after His resurrection, He commanded His disciples to preach the gospel of forgiveness, first at Jerusalem, where He well knew His murderers still resided. These striking facts are recorded for our imitation and seem intended to show that the Son of God died, not only to reconcile God to man but to reconcile men to each other.

He forgave the crime of murder on His cross; and after His resurrection, He commanded His disciples to preach the gospel of forgiveness, first at Jerusalem, where He well knew His murderers still resided. These striking facts are recorded for our imitation and seem intended to show that the Son of God died, not only to reconcile God to man but to reconcile men to each other.

Most Americans are very familiar with the Library of Congress and its massive collection of millions of books, documents, recordings, photographs, sheet music, and manuscripts.

Most Americans are very familiar with the Library of Congress and its massive collection of millions of books, documents, recordings, photographs, sheet music, and manuscripts.

From the time before the American War for Independence, black Americans served as

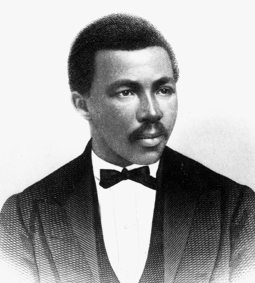

From the time before the American War for Independence, black Americans served as  [I]t is a matter of regret to me that it is necessary at this day that I should rise in the presence of an American Congress to advocate a bill which simply asserts rights and equal privileges for all classes of American citizens. I regret, sir, that the dark hue of my skin may lend a color to the imputation that I am controlled by motives personal to myself in my advocacy of this great measure of natural justice. Sir, the motive that impels me is restricted by no such narrow boundary but is as broad as the Constitution.

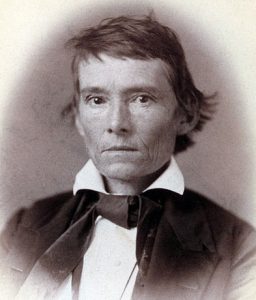

[I]t is a matter of regret to me that it is necessary at this day that I should rise in the presence of an American Congress to advocate a bill which simply asserts rights and equal privileges for all classes of American citizens. I regret, sir, that the dark hue of my skin may lend a color to the imputation that I am controlled by motives personal to myself in my advocacy of this great measure of natural justice. Sir, the motive that impels me is restricted by no such narrow boundary but is as broad as the Constitution. He [Stephens — pictured on the right] offers his government (which he has done his utmost to destroy) a very poor return for its magnanimous treatment, to come here to seek to continue, by the assertion of doctrines obnoxious to the true principles of our government, the burdens and oppressions which rest upon five millions of his countrymen [slaves] who never failed to lift their earnest prayers for the success of this government when the gentleman [Stephens] was asking to break up the Union of these States and to blot the American Republic from the galaxy of nations.

He [Stephens — pictured on the right] offers his government (which he has done his utmost to destroy) a very poor return for its magnanimous treatment, to come here to seek to continue, by the assertion of doctrines obnoxious to the true principles of our government, the burdens and oppressions which rest upon five millions of his countrymen [slaves] who never failed to lift their earnest prayers for the success of this government when the gentleman [Stephens] was asking to break up the Union of these States and to blot the American Republic from the galaxy of nations.

On March 3rd, 1931, an

On March 3rd, 1931, an  At that time, attorney Francis Scott Key

At that time, attorney Francis Scott Key