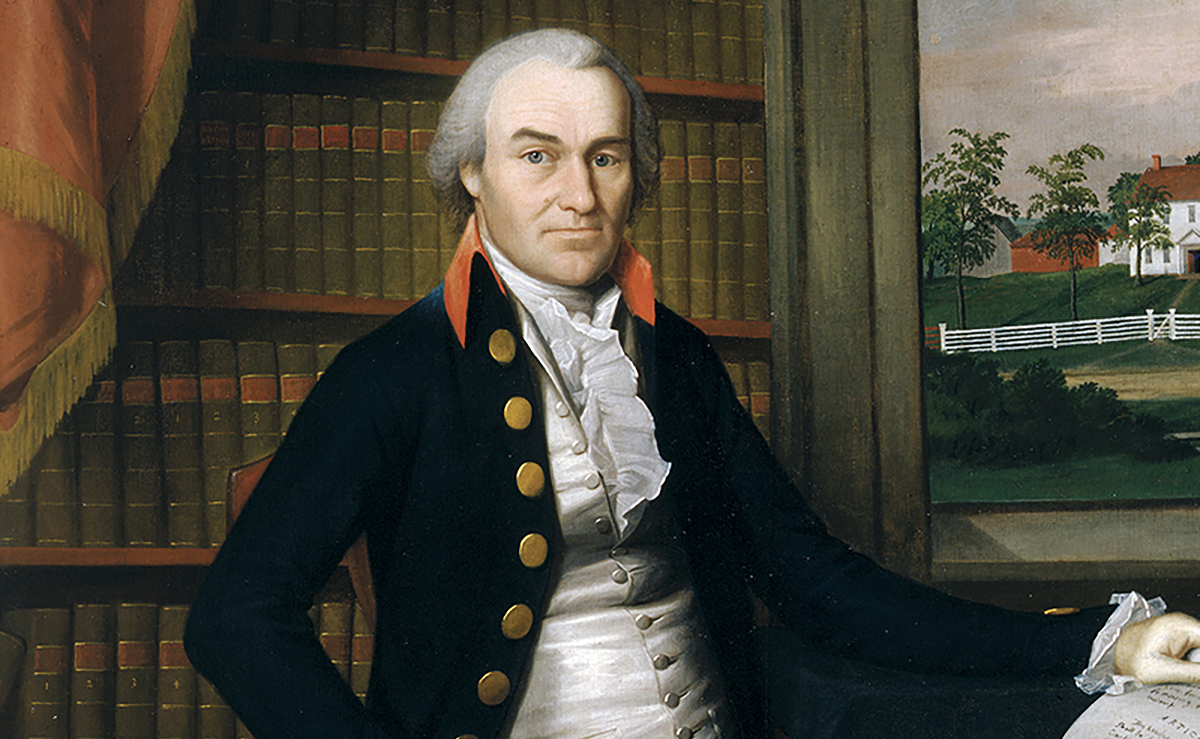

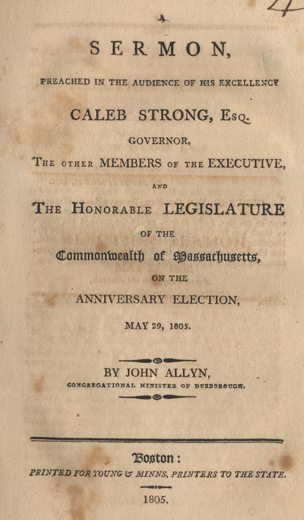

John Allyn preached this election in Boston on May 29, 1805.

SERMON,

PREACHED IN THE AUDIENCE OF HIS EXCELLENCY

CALEB STRONG, Esq.

GOVERNOR,

The other MEMBERS of the EXECUTIVE,

AND

The Honorable LEGISLATURE

OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS,

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

MAY 29, 1805.

BY JOHN ALLYN,

CONGREGATIONAL MINISTER OF DUXBOROUGH.

BOSTON:

PRINTED FOR YOUNG & MINNS, PRINTERS TO THE STATE.

1805.

IN SENATE, MAY 29, 1805.

ORDERED, That the Hon. Thomas Hale, William Brown, and John Phillips, (Essex) Esqrs. Be a Committee to wait on the Rev. John Allyn, and in the name of the Senate to thank him for the Sermon he this day delivered before His Excellency the Governor, His Honor the Lieutenant Governor, the Honorable Council and the Two Branches of the Legislature, and request a copy thereof for the press.

WENDELL DAVIS, Clerk of Sen.

ELECTION SERMON.

ROM. X. 1. & IX 1, 2, 3.

BRETHREN, MY HEART’S DESIRE AND PRAYER TO GOD FOR ISRAEL IS, THAT THEY MIGHT BE SAVED. I SAY THE TRUTH IN CHRIST, I LIE NOT, MY CONSCIENCE ALSO BEARING ME WITNESS IN THE HOLY GHOST, THAT I HAVE GREAT HEAVINESS AND CONTINUAL SORROW IN MY HEART. FOR I COULD WISH THAT MYSELF WERE ACCURSED FROM CHRIST, FOR MY BRETHREN, MY KINSMEN ACCORDING TO THE FLESH.

The most eminent personages of sacred history have expressed a peculiar attachment to the welfare of their own nation. That first divinely enlightened lawgiver, Moses, though nursed at the court of Pharaoh, and having a prospect of being advanced to the head of Egypt, yet, preferred affliction with his own people, the people of God, to the crown and treasures of Egypt. He chose to wander with his countrymen in a desert, where sustenance could not be had without a miracle, rather than to feast with a foreign monarch. The first impulse of resentment which agitated his breast was toward an Egyptian, who did wrong to one of his brethren, oppressing him with a burthen. When his people had “sinned a great sin,” in making the golden calf, whereby their title to the promised blessings of Canaan was forfeited, Moses intercedes, 1 “if thou wilt not forgive their sin, blot me I pray out of thy book which thou hast written.” He chose death rather than to see the miseries of his people, or would willingly submit to it, if their pardon could be purchased by this sacrifice. This natural affection to his own race, invigorated by religious faith, afterward unfolded itself in the most patient and laborious services of patriotism.

The great Author and Finisher of the Christian faith, in this respect, was like unto Moses. While he exercised the most self-denying and disinterested benevolence, productive of the most substantial blessings to mankind, his personal ministry was restricted to the Jews. Jesus the true light came to his own; 2 he did this from affection as well as by divine appointment. Being partaker of flesh and blood, he took not on him angels but men, and the seed of Abraham in particular. 3 Anticipating the unexampled tribulation, which awaited the unbelief and sins of his countrymen, he uttered that pathetic apostrophe, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem—how often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye would not!” 4 Jesus Christ, the image of the invisible God, 5 and an exemplar spotless and undeviating, manifested the whole series of limited affections. He cherished the ordinary sensibilities of domestic life, 6 the more generous emotions of private friendship, and to these, added the display of the most fervent love to his country, with tokens of unparalleled grace and compassion towards mankind.

After the evidence of such a witness, it is not necessary to vindicate any sentiment by the subordinate authority of prophets and apostles. Indulge me, however, in two instances relating to the present subject.

The prophet Jeremiah, when Israel was carried away captive, and Jerusalem became desolate, sat weeping, and bewailed with this lamentation: “How doth the city sit solitary that was full of people! How is she become as a widow! She that was great among the nations and princess among the provinces, how is she become tributary! 7 O that mind head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the slain of the daughter of my people!” 8 The pathos of the prophet’s lamentation, on account of judgments already executed, is equaled only by the ardent language of the apostle in the text, in which he deprecates impending calamities. “My heart’s desire and prayer to God for Israel is, that they might be saved. I say the truth in Christ, I lie not, my conscience bearing me witness in the Holy Ghost, that I have great heaviness and continual sorrow in my heart. For I could wish that myself were accursed from Christ, 9 FOR MY BRETHREN, MY KINSMEN ACCORDING TO THE FLESH” Oppressed with the presentiment of that unparalleled tribulation, which awaited his countrymen, his bowels yearned with compassion, and his most affectionate prayers ascended to God in behalf of his kinsmen and brethren according to the flesh.

But why such a limitation of benevolence? Why such deep regret on account of the destruction which impended the Jews, when the spirit of prophecy might have taught the apostle that like miseries awaited the crimes of other nations? Why not from the prime minister of the gospel of peace on earth expressions of more extended sympathy? Why not an imitation of the Father’s love, who is no respecter of persons, and whose blessings flow, at times appointed, on Jews and Gentiles?

It is replied, that as “man was made for his species by the Christian duties of universal charity, so he was made for his country by the obligations of the social compact.” 10 Patriotism is no more incompatible with general benevolence, than the more partial affections of domestic life are with patriotism. General benevolence implies particular; it includes the limited affections; it is a seminal principle in the heart, producing, in just measure and at proper seasons, the fruits of beneficence to our family, friends, fellow-citizens and fellow-men. While it propels to every useful exertion as opportunity is presented, conscious of imbecility and obedient to the emotions of nature, its beneficent hand is most frequently opened to comfort and supply the household. Indeed, as the domestic affections may be cherished and expressed, without any infraction of the maxims of justice and mercy to our neighbours, or encroachment upon the rights of the commonwealth, so these rights may be respected and the duties of patriotism be performed, without any infringement on the obligations of humanity.—It is then no proof that the apostle Paul was destitute of general benevolence, that he had an ardent love to Israel, his brethren and kindred according to the flesh.

While the patriotism of St. Paul operated according to the dictates of nature and the necessities of man in a state of society, it received an accession of strength from his reflections on the invaluable privileges which had been long participated by the chosen people of God. He seems to assign a reason for his love to Israel in the words subjoined to the text: “I could wish myself accursed from Christ for my brethren—to whom pertaineth the adoption, and the glory, and the covenants and the giving of the law, the service of God and the promises; whose are the fathers, and of whom concerning the flesh Christ came.” Why this particular enumeration of national honours and privileges, unless because a grateful participation in them was intimately associated with deep solicitude for the future welfare of his fellow participants? He is himself an illustration of his own description of charity, when he says, “if one member be honoured, all the members rejoice with it; and if one suffer, the rest suffer also.”

Were it necessary, in explaining and vindicating the patriotic character of St. Paul, it might be further urged that his love to his brethren was exercised in due subordination to the will of God, and the highest demands of philanthropy. Obedient to the voice from heaven he resisted his tender desires after his brethren, and pursued his mission to the Gentiles. He preferred compliance with the invitations of general benevolence and the will of God to the gratification of his limited affections. Though willing to be accursed from Christ for his brethren, without hesitancy, he acquiesces in the designation, “I will send thee far hence to the Gentiles.” 11

When we consider the order and progress of our social feelings, and weigh the authority of so great an exemplar as the apostle Paul, can there be any room doubtingly to inquire whether patriotism be compatible with the spirit of Christianity? And why does a celebrated modern writer 12 consider patriotism as excluded from the Christian system of moral duties? If indeed this term, when strictly defined, import a “disposition to oppress all other countries to advance the imaginary prosperity of our own; and to copy the mean partiality of a parish officer, who thinks injustice and cruelty are meritorious, when they promote the interest of his own inconsiderable village; if patriotism has ever been the favourite virtue with mankind, because it conceals self-love under the mask of public spirit,” Christianity, indeed, condemns it. Such patriotism does not approach, in degree or extent, the benevolence of the religion of Christ. But why degrade the term by such an exposition? Have there been no examples of a generous and laudable love of country? Will not fact justify the assertion, that those who are affectionate in limited circles, are seldom deficient in philanthropy? The kindest husband is probably the most helpful neighbour; this neighbour the most peaceable citizen; this citizen the most effective soldier; and such a soldier, educated in the different grades of social life, will the most readily weep over the ruins of war, cordially bewail the calamities of mankind, and conscientiously respect the obligations of humanity. It is, therefore, no proof that St. Paul was, or that any other person is destitute of general benevolence, that they manifest a kind affection towards brethren and kindred, according to the flesh.

But since the name patriot has been often usurped by wicked men, and historians have sometimes sanctioned the usurpation, and the nations aggrandized have acquiesced in the bestowment of unmerited honours upon unprincipled generals and statesmen; it is proper to discriminate more minutely on this subject, and thus to remove from the idea of patriotism, any disgrace into which it may have fallen by its alliance either with the weaknesses or vices of the human character.

No pretences of patriotism extenuate, much less justify the least violation of the maxims of justice and humanity. That greatness, which is invariably attached to vital benevolence, spurns at that policy which is merciless and dishonest. This benevolence, whether exercised towards family, fellow-citizens, or mankind, renounces every advantage, which cannot be secured without encroaching on the rights, or disturbing the happiness of individuals. It is indeed the greatest absurdity to attempt to build up any limited interest, by means which, if universally adopted, would prove subversive of all society.

It is scarcely necessary to add, that all illiberal partialities towards our own country, and unfounded antipathies toward other countries, are excluded from the idea of Christian patriotism. Neither is there anything commendable in the puerile attachment of some to their native soil and climate; though innocent, it ranks no higher than a fondness for one’s nurse. We may, however, view these natural feelings with a favourable eye, when they appear to be associated with moral feelings, and to limit and to strengthen them.

But severe censure is the just demerit of those hypocritical pretences to patriotism, which are designed for the concealment of personal ambition. Every age and country produces political sycophants, who flatter, that they may rule or plunder their fellow-creatures. The numerous instances of this deception should make us slow in giving credit to the appearances of patriotism. The popular opinion is frequently ungrounded. To-day we hear, Hosanna to the Son of David; tomorrow, Crucify, crucify him. Many excellent men sleep in the grave of obscurity, and others have a name to life, who deserve oblivion. Discrimination dictates an eulogy upon the poor man, whose wisdom saved the city, but who was never after remembered, 13 and assigns him a much more conspicuous niche in the temple of fame, than more celebrated characters, who have the credit of loving the nation and building a synagogue. It is but just to distinguish the unalloyed gold of patriotism from deceitful imitations, and the meteors of a moment from the stars of the first, second and third magnitude, which shine through successive generations.

Excluding then from the idea of patriotism whatever is unjust, frivolous, selfish or hypocritical, it is then only commended, when defined to express an honest solicitude for the welfare of the community to which we belong, and a glowing joy at the just gains and improvement of our kindred according to the flesh; a deep and anxious anticipation of our country’s dangers, and affectionate prayers for its prosperity:–Or in fewer words, patriotism is to be commended when the profession is sincere, the means just, and the objects important.

The favourable hearing of this intelligent audience is solicited, while the speaker dispatches the practical part of his subject, and applies it to the occasion in our view; to the characters here assembled, and the times in which we live.

The most arduous duty of patriotism is to die in its cause, when required. Many names in Greek and Roman history, as also in the history of other nations, have been transmitted with veneration, for this reason, that they counted not their own lives dear to them, if they might but work some great deliverance to their country. Indeed, a greater oblation than that of life cannot be made for the common safety. But the call to embrace certain death is made but seldom, and but to few individuals of any nation. And if called, many worthy citizens might shrink from so expensive an offering for the public good. The spirit might be willing, but the flesh might be weak. With more frequency, we are called to hazard our lives; and when the justice of our country’s cause is clearly established in the mind, and the obtrusions upon our personal safety and possessions are violent and continued, whoever can ardently pray for his brethren and kindred according to the flesh will seek no dispensation from the ordinary casualties of war; but cheerfully obey a summons to the field. The state of peace, in which we live at present, renders any persuasive on this head unreasonable. By favour of Divine Providence, we are not required at present to decide on such trying demands of patriotism. More pleasant themes invite attention. The ordinary course of things in our times and country affords many opportunities of rendering patriotic services, and everyone may daily find some work of love to his brethren. Beside what may be exacted in the defence of our country against a foreign enemy, there are a multitude of other expressions of patriotism important in their nature, practicable by all, and especially by such, as occupy stations of influence and authority.

It is consoling to reflect that every individual, in whatever station, may reap the honour of patriotism and enjoy the complacency which springs from useful actions, by cherishing in himself and others benevolent opinions and feelings, by setting an example of ready obedience to the laws, by giving support to institutions of public utility, by aiding in the establishment of such new regulations as the common good requires, by occasional acts of charity, and above all, by exhibiting an undefiled pattern of Christian virtue and godliness.

But perhaps these objects seem distant and general, and the effects produced by individual exertion almost imperceptible. We may, however, find a new spring of animation and diligence in considering how much good may be done to our country by only pursuing with zeal and fidelity the business of our respective vocations. It falls but to few to die for the nation, and an opportunity may seldom be afforded of contributing to the erection of some great edifice; yet everyone, in all times, by well discharging the duties of his sphere and station, may build up the interests and increase the happiness of his country.

The social body is composed of various members, mutually connected and dependent. Though some be deemed less honourable, they may not be less necessary than others. As the eye, the ear, the hand, the foot of the human body, cannot say one to the other, I have no need of you, but all in their respective places have indispensable uses; so, in the commonwealth, each citizen has dome gift or function, by which he may become a contributor to the support and pleasure of the whole body. In every society there is much mutual dependence. “The king himself is served by the field.” 14 All the various classes of men derive subsistence from each others’ power or favour. The most essential labours are those of the field. The different fabrications of the artist are either useful or convenient. The rich would be less happy without the poor to administer to their leisure and ease; and the poor, in turn, are profited by the stewardship of the rich, whose enterprise, providence and economy enable them to reward their labour, and relieve that indigence, which springs from indolence, wastefulness, and vice, or from sickness and misfortune. The young sustain an important relation to the aged, whose infirmities and sorrows it is their province to bear and mitigate, as well as perform the manual service, and endure the hardships of life; and the young may reap a full reward from the counsel of ancient men, matured by experience and rendered impressive by grey hairs. We need not therefore every despond with the idea that we are unable to serve the community; for keeping in the line, that nature and providence have marked out for us, we may effect a multitude of purposes useful to society. By assiduity in our professional labours, without any uncommon exertions and sacrifices, we may reap the praise of serving our country and generation.

But the subject of patriotic duties more properly embraces the consideration of certain weighty interests of society, in the advancement of which it is necessary we should all unite, be our particular vocations what they may. There are some burdens, which may be lifted by individual strength; others require the united force of the whole community to raise and support them. The opinions of all parties must be embraced, when it is said, that patriotism requires the watchful preservation of our constitution and liberties—the cultivation of agriculture arts—the diffusion of knowledge—and, above all, the promotion of a religious spirit, fruitful of good works.

I. The first duty of patriotism (especially in our country) is to PRESERVE OUR CONSTITUTION AND LIBERTIES. Mankind have entertained different ideas on the subject of civil constitutions, and have adopted different forms, “according to the different habits, genius and circumstances of the people.” With us there ought to be but one opinion; and, as the result of this opinion, the most decided support given to our republican institutions, as best adapted to promote the happiness of all ranks in society. Some parts of the superstructure may with propriety admit of occasional alterations; but the elective base, and those constitutional pillars of freedom, upon which we are compacted together, require vigilant protection. There is danger of innovation without improvement, of annihilating one point after another, to facilitate the designs of party, and serve the purposes of personal ambition.

Our fathers, in the most serious exercise of their understandings, and influenced by the most disinterested motives, adopted and established those civil constitutions, by which we have been protected, and to which we still look for protection. We have reason of full confidence both in their judgment and patriotism, from the experience of safety and prosperity. The lover of his country will watch against every encroachment on established rights and liberties, and especially such as have for their object the perpetuation of civil power in the hands of a few. But what are the means to this end? To what expedients must we have recourse in securing tour present privileges? No mean, no expedient is of more certain operation than the appointment of wise and good men to manage our common interests. Let all classes of citizens unite in this point, viz. To place honest and able men in their public councils. Can we be so infatuated as to think our constitutions and liberties ever safe, when we entrust civil power to men whom we discredit in private transactions? The governing part of a nation ought to be men of unimpeachable justice, prudence, temperance, and exemplary goodness. For if men have lost the moral government of themselves, how shall they direct the affairs of the public with reason and equity, and how can we suppose they will respect the rights of the whole people, who do not respect individual claims.

It may be added, that the corrupt example of men in station is peculiarly contagious and destructive. The pagans imitated the supposed practices of their gods. Gods on earth equally propagate their vices. And as it was formerly in vain for the philosophers to arraign the vices of heathen deities, so now it is equally fruitless for the preacher and moralist to inveigh against vices made reputable by official eminence. There is special reason to fear that our rights and liberties will be impaired and lost, and our national manners corrupted by unprincipled and immoral rulers.

So much evil is to be apprehended from this source, that it may be established as a prime duty of patriotism in every citizen to exercise his elective power with caution, and entrust the administration of public affairs only to men of sound minds and virtuous habits. Without this preventive, that treasure of independence and freedom, which our country so long and so nobly bled to acquire, will be dissipated and irrecoverably lost. We often look to political expedients for the preservation of political blessings; but they will all prove deficient, if the general course of our public affairs be not directed by wisdom and uprightness. To this point then, let all collect, and commit the custody of our political tables to men of unostentatious wisdom and experienced fidelity. Thus shall we preserve and perpetuate our constitutions and liberties.

II. But the attainment of this object is intimately connected with another branch of patriotic duty, the GENERAL DIFFUSION OF KNOWLEDGE. We have a text on this subject, the writer of which, and the chapter containing it must be recollected by every individual in this audience. “In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion be enlightened.” 15 Whoever loves liberty and the government of laws will cultivate seminaries of learning. He will manure and weed every plot where seeds of instructions have been sown, and hedge in new enclosures, that “children’s children may go in and find pasture” to satisfy the hunger of their minds. It may be a fact, that ignorant subjects are most peaceable and submissive, and that learning, beyond the sphere of one’s own occupation, has sometimes a tendency to beget uneasy and aspiring sensations. Under despotic governments, sound policy may forbid the dissemination of knowledge; but we profess to value liberty, as conducive to the safety, peace and improvement of man. Let us then provide against both its abuses and its loss. The preservation of it can be insured by no means of more infallible operation than that of enlightening the public mind. The wise sometimes, the ignorant always are led by their passions. By mental cultivation these passions are subdued in part, and the remainder restrained. The uninformed are easily excited to rebellion by coarse and noisy eloquence; and there are no establishments or measures, however wise and salutary, but must yield to the vandal rage of an ignorant populace. The light of knowledge also tends to harmonize the feelings of men, to prevent the unhappiness arising from a collision of manners, and dispose them to endure that heterogeneous quality of each other’s habits, which, to a certain degree, is incurable. Beside these considerations, showing the importance of diffused information, how unqualified are the ignorant to designate wise and honest agents from the general mass for the purpose of government. Blind electors will not probably choose seeing guides. The issue is still less problematical, when the blind are leaders of the blind. The grossly ignorant and immoral cannot subsist under a free government. Among such, civil power must be concentrated in the hands of one or a few, and profound submission to its most arbitrary exercise be the only means of preserving any order and justice.

Impressed with these convictions, the patriot will render every support and encouragement to teaching and learning, and the diffusion of useful information through all ranks in society. Though smatterings of knowledge may often produce pedantry, and though the poet has said, “A little learning is a dangerous thing,” yet boorish ignorance is both more unpleasant and dangerous.

But in devising methods for effecting this object, it must be recollected, that knowledge is not to be gained, after arriving to adult age. Some improvement may made on the stock acquired, but few additions to it can be expected. The nurture of the mind must be commenced early. It is then flexible, active, and partakes of a higher degree of susceptibility, than belongs to riper years. It is a most ingenious and instructive figure, which someone has adopted, to illustrate the necessity of early instruction in morals, who says, speaking of the young, “they must be died in the wool.” This idea applies as well to the principles of knowledge, as to those of morality. . The colours communicated after the cloth is made will soon fade, if not entirely wear out. It is hence easy to perceive that the diffusion of knowledge imports something more than circulating party pamphlets, newspapers, and sectarian theological tracts, 16 which, like some of our political schoolmasters, are not always the better for being of imported origin. The Christian patriot, in his efforts to spread knowledge, will first light the taper at home: he will teach his children and dependants, morning and night, in the house and by the way. And since few have both the ability and leisure to do this, it is necessary to patronize young men of respectable character and suitable talents, and give them ample encouragement to enter upon the laborious duties of common schools, that the profession of teaching may be pleasant and reputable, if not lucrative, to the teacher. In producing these teachers, and thus advancing the interests of early education, there must be primary schools for their instruction. The institution of colleges, where the higher branches of knowledge are taught and learnt, is indispensable for this as well as other purposes. Though they may be complained of as aristocratic, since the advantages of education they furnish are necessarily limited to a few, yet great is their influence upon political freedom and public improvement. Beside affording the community qualified teachers of youth, their effect is discovered in the debates of our public assemblies, in the weekly services of religious teachers, and the general style of reasoning throughout the whole community. Admit that they discharge their streams with partiality, watering here and there a favoured spot, yet providence has opened numberless channels, by which their salutary waters are diffused over the whole face of the commonwealth. We have not much to fear from literary aristocracy. Though knowledge be power, and superior intelligence as well as property extends the influence of the possessor; yet science, truly so called, has no corrupting effect on the heart. The pursuit of it tranquilizes the mind and reforms the manners. We may be assured, that if the larger windows of light be shut, the whole mansion will be soon involved in barbarian darkness, with which despotism is inseparably connected.

The Christian patriot will therefore cherish in his own and in the minds of others a veneration for the larger seminaries of instruction, and their founders, and daily pray that “healing salt may be cast into these fountains of knowledge.”

III. Although the defence of liberty and the spreading of knowledge are objects of high concernment in the view of patriotic minds; yet the article on which we are about to enter must be magnified in its importance. “Of all dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, RELIGION and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who should labour to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician equally with the pious man ought to respect and cherish them.” Thus spake one, “by whom many worthy deeds were done to our nation,” at a time too when no personal motive could possibly bias his counsel.

The opinion of some that RELIGION is not to be associated in any degree with political affairs, that society may flourish without its aid and influence, it may not be needful to confute in this assembly; if it were, we would demand an instance of a people, altogether profane, regardless of an oath, destitute of religious fear, who have subsisted in peace and order, and found growing prosperity and happiness.

What part of nature is supported without God? Do the planets keep in their spheres? Does the earth revolve? Does the soil shoot forth the blade of grass? Does health nerve the limbs and cheerfulness expand the soul, without the all pervading spirit of the Most High? Nay. How then shall the social virtues bud and grow independently of the same cause? How shall order, strength and manhood accrue to the social body without any portion of divine influence? And through what channels can this influence flow, but through the mind and heart?

Religion may be considered as to its theory, its spirit, and

practice. Its theory involves the consideration of things infinite, eternal, and transcendently excellent, viz. God, immortality, and the immutable discriminations of holiness and sin. Its spirit implies such emotions towards God as are associated with everything mild, joyful and sublime. The practice of religion, or the sensible forms of it, conduce to the two first mentioned ends, viz. the knowledge of its theory and the exercise of its spirit. Religion doubtless subsists in different persons and communities, and at different periods of time, in various degrees of purity. But without some respect for a Supreme Lawgiver, there is no basis of obedience to the laws of morality. Even a weak sense of religion, clouded by ignorance and intermingled with the vanities and weaknesses of human nature, secures the practice of many duties, which can never be successfully enforced by civil laws.

It is necessary, however, to distinguish the religion, which is useful in the preservation of social order and happiness, from certain corrupt and unlawful establishments which have been made in many countries. Correct ideas of religion are not obtained by reading the debates of the council of Nice, the minutes of a Romish conclave or Protestant synod. Most, if not all ecclesiastic, academic, as well as legislative disquisitions on this subject have shed darkness rather than light, and unfolded the character of the man of sin, rather than that of the prince of peace.

Useful religion is also to be discriminated from the wild enthusiasm, excited by field oratory, and the anti-social gloom of the cloister. Religion has often been defiled and rendered unprofitable and unamiable; and is always tinctured, by the education, constitution, and moral habits of men; yet even in its most imperfect forms, it is accompanied with some meliorating effects. In this recommendation of religion as useful in a state, we are not so much concerned to make any casuistical statement of its metes and bounds, as to illustrate its general influence on the conduct and happiness of mankind. A scantier portion of religious knowledge and sentiment may answer useful purposes in society, than will be necessary to our obtaining a part in the future inheritance of saints.

In these remarks on the effect of religion, the epithet Christian, though omitted, is understood. For to us there can be no middle way between embracing the doctrines of the gospel, and resorting to skepticism and irreligion. We can have no motives and feel no impulse to adopt pagan idolatry or Mahometan imposture. And it is a thesis, from the defence of which no believer need shrink, that every person who experiences the smallest excitements of a religious nature, will eagerly read and hear the report of Jesus Christ. Is anyone alarmed by anticipations of the punishment of his sins? Is anyone conscious of inability to keep the law? In the gospel are promises of pardon and aid. Does anyone hunger for the bread of life? From this source it may be procured. The neglect or rejection of Christianity, when fairly proposed, in most cases indicates religious unsusceptibility, and we may add, an equal deficiency of moral feelings.

We are sensible there are many sects among Christians, some of which claim an exclusive patent right to the keys, which unlock the door of divine truth and the gate of heaven. Some incorporate the logic of the school with their Christian divinity; their liturgy does seldom comprise the Lord’s prayer, and their confession of faith is such as might be framed by men, who forget that the Sermon on the Mount was ever preached.

Others are disposed to monastic life, and think they never serve God, but when in the act of praying. There are, too, lordly Christians, who would bring over again the mischievous farces of national and ecumenical councils. Some, of unfeigned piety, but illiberal minds, deem nothing religion unless it be measured by their line, and its fervor be excited to a given point, which is also to be ascertained by their thermometer. In this collision of sentiment, the Christian patriot may hesitate what course to pursue, what tenets to defend, and to what establishment to adhere. Shall he embrace the church, whose articles of faith are multiplied and circumstantially defined? Possibly he may neither get any good himself or do any to the commonwealth. Shall he make the matter of rites and ceremonies a turning point? He will be fed, neither with “milk nor meat.” Let every man examine his faith, his feelings, and his practice by the word of God, permitting no inferior authority to warp his decisions. In promoting the interests of religion among his fellow-men, let him propagate those truths which are plain and important; nor feel obliged to satisfy the inquisitiveness of bigots by avowing the party of Paul, Apollos, or Cephas; contented if it do but appear that he hath been with Christ. So far at least as the welfare of society is concerned, there is but one essential point, viz. to convince those who believe in God that they ought carefully to maintain such good works as are profitable to men. Whilst these are indispensable to the character of the disciple, they form the sum of the religion of the patriot. As to those, who act a contrary part, and endeavour by their sophistry or their ridicule to extirpate that little respect for Christianity, which at present subsists, the most favourable remark which we can make was made by our Saviour on those, who were active in his crucifixion, “they know not what they do.” 17 The Christian patriot will cherish the vital sentiment, the inward operation of religion, and judge in all cases of its strength and purity by the fruits. “How shall I do this great wickedness, and sin against God,” is an exclamation, which, when dictated by the heart, and verified by the conduct, ascertains with sufficient clearness the power of religion in any man’s breast to entitle him to our confidence, respect and love.

Beside the influence of religion upon morality in general, it merits consideration, that whatever be the means or objects of patriotism, its spirit is purified and its zeal quickened by this principle. No virtuous emotion can long subsist, much less be excited to a high degree, in an unsanctified heart. Love to man, whether more or less limited as to its objects, must be frequently invigorated by the stimulations of piety. It will wax cold, and the number of its labours be diminished, unless its fire be renewed by a spark from the altar. 18

Beside the cardinal interests of LIBERTY, KNOWLEDGE and RELIGION, there are other objects of subordinate value soliciting the attention of him who loves his country.

Agricultural improvements, rural and domestic economy, the introduction of useful plants, roots and grains, rank high among SECONDARY TOPICS. He, who should discover one grain of wheat so much earlier than the common kind, as to be exempt from blast; and who should propagate it with effect, will in the result have done more good to his country, than he, who, by conquest or purchase, should add the mines of Mexico to our national domain. We ought to know who first introduced and encouraged the cultivation of that vegetable, which is next in value to bread. If the plough, in its present improved state, had been the invention of one man, a colossal statue, larger than that of Rhodes, would be too little to perpetuate the remembrance of the inventor. As the ancients contended about the place which gave birth to Homer, we, as philanthropists, have much more reason to respect the character of Rumford, 19 and honor ourselves by some indelible register of his name. The happiness of the human kind is an aggregate made up of particulars, some of which escape the observation of little and great minds. The vision of the former does not extend far enough, and that of the latter extends too far, to make discovery of the truth. Whoever surveys the map of our country, and considers the variety of its soil and climate, will see how much our interest and comfort are involved in the improvements of husbandry, compared with which, the mechanic arts and commerce are of secondary importance. The number of people, who subsist by these, must ever be comparatively small. Commerce indeed is a handmaid of agriculture, by opening a market for the surplus produce of the earth. But of what other value are the returns? In a moral view, the commodities of the East and West Indies are of little service. Ought it not to diminish our relish for some of them, that they are the produce of slavery? Such was the sensibility of David, that he would not, though thirsty, drink of water brought from the well of Bethlehem by three brave men at the hazard of their lives. He called it the blood of those who went in jeopardy of their lives. And yet we, Christians, advocates for liberty and the rights of men, stimulate our appetites and feast our palates, daily, and without remorse, upon luxuries produced—but I stop, lest something unwelcome should obtrude itself in regard to the social condition of some of our sister states. To revert to our subject. Many imported commodities encourage idleness, and engender corruption and effeminacy. By establishing two great interests, commercial and agricultural, unhappy alienations among citizens are excited, while the merchandize exposed on the ocean allures the cupidity of foreign pirates.

Provision for the subsistence and morals of the poor is a duty of patriotism. In every country this class is numerous; more especially where population increases and the means of subsistence are unequally divided. In our country, poverty arises from idleness, want of economy, and moral debasement. The patriot will deem it no trifling object to infuse into the poor a “spirit of decency, a love of economy, a desire of knowledge, and a regard to character.” In ordinary times, few services can be rendered to our country of greater magnitude than the promotion of the above objects. Abjectness and vice in the character of the poor are disgraceful to the laws and manners of every country. In some countries this subject is truly awful, and invites the most active services of benevolence. The prevention of this evil invites the most serious consideration of active patriotism in our own.

When we reflect the SPIRIT OF THE TIMES in which we live, it will appear evidently to be the duty of every patriot to set an example of sobriety and temperance, to promote peace and mutual confidence, to dissipate, by honest and prudent means, those pestilential vapours which hover in our political atmosphere, and to breathe out, in conversation and behavior, the spirit of meekness and urbanity. What we experience at this day is not new in the world. In navigating the sea of popular liberty, it has always been found tempestuous. The rich and the poor, the north and the south, form into parties to injure and destroy each other; and under the specious cover of preserving liberty, liberty is at length annihilated. To this danger we stand exposed. A part of the time we contend about principles and measures, but the whole time about men. Our restlessness and folly render imminent that demolition of freedom, which other free states have experienced. All lovers of their country, not putting far away the evil day, will labour to avert its calamitous issues.

With a view to this end, we naturally ask, are there not some untried expedients of peace, harmony and mutual confidence? Instead of debating any longer on the points of difference, let it be inquired coolly in how many things men are agreed. Instead of using harsh and scornful language, and wantonly shooting arrows dipt in poison, let men consider that a steady hand, a tender heart and gentle tongue are qualities most useful to the patriotic surgeon, who would heal the festering wounds of division. The “tongue of the righteous is health, his mouth is a well of life; his lips disperse knowledge; his communications are good to the use of edifying, and minister grace to the hearer.” Let also every man shew more solicitude that his fellow-creatures be well informed and governed, than that his particular opinions be adopted, or he himself allowed to share in the administration of public affairs. And above all, as a fundamental recipe in healing divisions, let every man govern himself, not serving his own interest at the expence of justice, or seeking revenge at the expence of charity. Self-government is striking the ax at the root of the tree; it is like drying up the sharp humours and cooling the feverish fluids of a diseased body. “Could men but be persuaded to prefer the public peace and welfare to their own private advantage; to seek fame, honour, authority or wealth in subordination to things of greater moment; in claiming their own rights to allow others theirs; to smooth the rugged waves of each other’s passions with the oil of kindness; soon would the tumults and strifes, which now exist, be hushed, and a happy calm spread itself over the face of the earth.” Should we continue to suffer our judgments to be perverted in the plainest cases; to invade the peace of individual breasts; to dissolve the tender charities of blood and kindred on the pretext of difference in political opinions, more baleful ills must be expected than we now experience; public order will be interrupted, the foundations of society endangered, and the effusion of blood and the establishment of despotism close the tragic drama.

The offices and objects of patriotism, which have been particularized, interest exclusively no one class of men. The powers and opportunities of individuals are indeed dissimilar; but everyone, the peasant, the prince, the villager, the citizen, the husbandman, mechanic and scholar, may all, in their respective places, do good to their country. And even the most inferior labours of beneficence, when stimulated by honesty and benevolence, are to be praised, and the Supreme Rewarder above will not forget them. Remember the widow’s mite: though small, compared with the gifts of rich men, yet the piety and penury of the donor made it a respectable offering. Let it console the obscurest individual, that though he is able to throw but a mite into the mass of common improvement and happiness, yet he shall in no wise lose his reward. Be it so, that his circumstances are straitened and his capacities small, yet there is some one good thing which he may do. Let him plant a tree; meliorate one acre of soil; diffuse love in his family and neighbourhood; give impression to one moral truth upon the tender and the real effect of his patriotism shall outweigh that of many statesmen, philosophers, and conquerors, who have had the name of serving their country. We are apt to be weary of well-doing, more especially if the benefaction seem like a drop in the ocean; but how are we sure this figure is just? With respect to moral influences, it certainly is not just. If “one sinner destroyeth much good,” 20 one righteous man may be the instrument in Divine Providence of repairing the ruin. Good men are the salt of the earth. Let them awake and come to their work of love and labours of patriotism, not disheartened by the fewness of either their powers or means. The feeblest man may remove a small stone from the traveler’s path, and perhaps save his life. The most obscure and indigent man in society may apply a healing medicine to one moral disease, stop the progress of one infectious particle, close the avenue of one crime, and the effect of such exertion shall extend to future generations. It is in the aggregate of such labours, that the commonwealth shall experience growing prosperity and happiness.

But THIS OCCASION and THE RESPECTABLE AUDIENCE here convened remind us of that extensive field of usefulness, which is occupied by men in PUBLIC STATIONS. Legislators, Magistrates and Ministers of the Gospel possess many ways and means of contributing to the public welfare. To them especially we look for an example of patriotism. A tendency must exist in their vocation to sequester their thoughts from private and local interests, and to expand their social feelings. Though they live by others, yet in a peculiar sense they live for others. Strictly speaking, there is no honour in station. “It is more glorious to be a good subject than a bad ruler; to be a good disciple than a bad teacher.” 21 There is neither any debasement or exaltation, absolutely such, but that which adheres to the moral character. Yet there are certain posts of eminence, those placed in which are highly responsible for the result of their example and administrations. These posts are occupied by the Civil Ruler and the Christian Minister.

Consider yourselves, O YE RULERS IN THE EARTH, as vested with eminent powers of doing good. It is yours, to facilitate the acquisition of right; to protect the hedge which separates individual property; to patronize improvement, and thus to meliorate man’s condition. Great are these objects of your appointment and authority. Think not merely of engrossing the honours and emoluments of station; but scrutinize with eagerness the means of rendering mankind more happy. Ye are the agents of God to punish evil doers, and to bestow praise on those who do well. The lives, the estates, the reputations of men are, in a qualified sense, committed to your keeping. Offices of such trust as yours will never be sought after, except by the vain and ambitious. The solicitude of a patriot, excited by a lively sense of responsibility, more than outweighs all the honours and profits of his station. An awful account must be rendered at the final day of retribution, if, through avarice and ambition, absorbing every feeling of justice and humanity, ye have desolated other countries or divided and plundered your own.

And consider also, ye MINISTERS OF THE SANCTUARY, the extensive influence of your functions and example. “Ye are an epistle, read of all men.” Evince your piety and patriotism by abounding “in faith, utterance, knowledge, diligence and love.” Instead of triumphing at the spread of those particular tenets, which ignorance, education or bigotry may have infixed on your minds, rejoice rather when you see the truths and comforts of the gospel exciting to resignation and benevolence, and the practice of those virtues, which dignified and adorned the character of your divine master. While with serious simplicity, ye illustrate the truth and maxims of Christianity, let your most concealed actions be as disinterested and upright as your public professions imply. Preach as often on purity of heart as on purity of faith. Be not eager to thrust yourselves into the chair of Moses. He who is the best servant to the church is the greatest. To shine in life and manners is a more suitable object of Christian ambition, than to shine in word and influence. Be not among the number of those who commend themselves; who encroach on other men’s labours. Feed the hunger, watch the wanderings of your own flock, nor seek to establish any intermediate guide between yourselves individually and the great shepherd of the sheep.

May God by his Holy Spirit assist and quicken all his ministering servants in Church and State, who now act on the theatre of public life; and may he sanctify others from the womb, to succeed in their stations, and even to display marks of superior excellence. May America produce a Fenelon to instruct the princes of our tribes how to exercise their power in the most beneficial manner; another Newton to unfold some hidden laws of nature, and fill the astonished mind with new transports at the sight of God’s power and majesty; another Locke to anatomize in some new and instructive manner the complicated operations of the human understanding; another Butler to destroy the fabric of infidelity, and raze it to the very foundation. May God, in the number of his heavenly gifts, supply all our churches with Doddridges and Wattses, who shall nourish and defend, with a well balanced zeal, the interests of orthodoxy, devotion, and charity. May he always provide and designate for the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness, to rule and to judge in every public department with equity and wisdom.

Let an affectionate regard for posterity stimulate us to the present discharge of patriotic duties. Whether high or low, private or public be our station, let this sentiment invigorate our exertions, that the improvement, virtue and happiness of the succeeding generation are inseparably linked with the diligence and fidelity of the present. Here parental and patriotic affections unite to encourage the same efforts. We are zealous to exhibit marks of elegance in our public buildings, and we devote the superfluity of our wealth to the purposes of many important improvements in the whole face of our country. But is there not infinitely more elegance and improvement in a body of youth, trained up in the holy nurture and admonition of the Lord? The Roman and Greek orders in architecture have infinitely less grace that the spiritual pillars of the Christian virtues. These virtues grace indeed the social building. To erect them on a stable foundation, and add some finishing strokes of moral beauty equally becomes the character of the Christian and the patriot. We rejoice in growing prosperity and wealth; but what wealth can a people boast, equal to the treasure of sons and daughters, walking in the truth, growing in stature, and by wisdom and virtue increasing in favour with God and man?

To dignify the acts of Government and give importance to this occasion, we have joined in a solemn procession to the house of God. How interesting is that procession of one generation after another, which the Author of Nature has ordained, and how desirable that we may have reason to believe, that in following our steps, our ancestors will not err. Sparta gloried in the military talents and achievements of her youth. But patriots and Christians will glory more in the knowledge and virtue of their children, in whom they had rather see an air of respect to the aged, than the stern visage of the warrior—the healthful complexion of charity, than the rough features produced by early toil and hardship. The military displays of a Spartan band excite not half so much interest in the peaceful and patriotic, as the youthful trains of our schools and academies, displaying at once the harmlessness of their purpose and the fervor of bloodless emulation.

While we leave to posterity improved roads, ceiled houses, literary institutions, salutary laws; let the higher ambition pervade our hearts of transmitting to them unsophisticated principles of religion and government, with the purest maxims of Christian morality. God forbid that we should encumber the opening minds of youth with our errors and follies—that they should inherit our factious dispositions, and have a pretence impiously to complain hereafter, “The Fathers have eaten sour grapes and our teeth are set on edge.” 22 May they rather have cause to eulogize us, as we have to eulogize our predecessors.

It may serve to inspire all with an affectionate regard for the common welfare to consider the examples of a patriotic spirit, which are exhibited in the annals of our country. At the glorious era of the American revolution, men of the purest and most active patriotism came forward into the public service; many of them sleep in the dust of the earth, and the few, who survive, have either retired or must soon retire from the field of public usefulness. We shall reap more instruction and be fired with warmer solicitude for the good of our country, by weighing the spirits and pondering the paths of some deceased patriots and others, now in the decline of life, than can be derived from all the empty harangues and fruitless diligence of the whole tribe of mushroom declaimers about the public good.

Those, who in the prime and vigour of life, at the epocha of our revolution, conducted the arduous struggle for independence—who planned and matured those constitutions of government, under which we live; who wrought in the vineyard from the earliest period of difficulty and danger, deserve gratitude and confidence, prior to those, who, stepping in at the eleventh hour of public labours, presumptuously claim the honour and recompence of doing the whole work. From these early patriots we may select many models deserving imitation. There is one model of preeminent beauty and proportion, which we trust may be mentioned without exciting any jealousy even in the hearts of the most envious and proud.—The name of Washington should be pronounced on this anniversary throughout all generations. Let all remember with what dissidence he received power, with what anxious solicitude for the public welfare he exercised it; and how willingly he resigned it when its destination was accomplished. His benevolence was not a transient sensibility, producing a flood of tears, not a spasmodic convulsion, now opening, then shutting the heart more close than ever; but it was a strong vibration, propelling to one uniform series of patriotic deeds from the morning to the evening of his precious life. The leaves of his patriotic professions were few; but the fruits, those signs by which a good tree is known, were large and sound. May not that Goth, who shall ever presume to deface that monument of admiration and gratitude, which his patriotic virtues have raised in the American breast, share the fate of Miriam when she spake evil of Moses, and become “leprous, white as snow.”

In surveying this respectable assembly, our thoughts have been for some time directed to a CHARACTER, in addressing to whom the respectful congratulations of the Commonwealth, private inclination concurs with a sense of propriety. Both prompt us to express a satisfaction in seeing the chair of supreme executive authority occupied by one, whose life illustrates the subject of patriotism. May that divine promise be fulfilled upon him: “When a man’s ways please the Lord, he shall make even his enemies to be at peace with him.” 23 May the Governor of this Commonwealth ever be a man, on whom the viperous tongue of malice and envy cannot fix for a moment the imputation of injustice, ambition, hypocrisy, or impiety. And may the citizens of the State never banish from their public councils an Aristides, because vexed with continually hearing him called the Just. 24

We tender our political homage to the Second Magistrate in the administration of Government, to the Council, to the Two Branches of the Legislature, who, we expect, will teach their constituents by all their deliberations to look more at principles than persons,–at measures than men. The state of things among us is not to be disguised. Such disguise indicates a contemptible timidity, unbecoming the free spirit of patriotism and religion. We beseech you all, by the manes of departed patriots and the hoary locks of the living, no longer to sever us in two, but by example, excite us to rise up and build the wall of common safety and defence. Deny yourselves the pleasure of petty conquests, and command our respect by seeking the things which make for peace and the edification of the whole body. You have received the suffrages of your constituents. It will be far more honourable for you, if by wise and patriotic services you gain and keep the confidence of the worthy. Then the ear which hears you shall bless you, and the eye which sees you shall witness favourably.

Every vice receives a currency from your example. With the image and superscription of a ruler, it passes, if not with the deserving and good, yet with the mass of mankind, who do not examine with care any coin, if it only satisfy the lust of present gratification. In men in your station and of your character, we expect to see an exemption from both the follies of childhood and the faults of old age. In you we expect a happy union of wisdom and patriotism, and hope to find you never departing from beneficent purposes—never unsettled by casual praise or dispraise, but founding a reputation with the people only by the sanction of self-approbation.

While as citizens of the commonwealth and members of the American union, we mutually embrace and provoke one another to love, let our practice be honourable and our feelings kind towards all men. The cultivation of a public spirit and the enforcement of patriotic duties have no necessary tendency to foster a contracted and exclusive spirit. The liberal genius of Christianity is to break down every partition wall created by the vanity, prejudices, or selfishness of mankind. And he who is our peace suffered on the cross, that he might reconcile us to God and to one another. The gospel is announced to those afar off, as well as to those who are nigh. While we express “our hearts’ desire and prayer to God for our brethren and kinsmen according to the flesh,” let no supplication be concluded without fervent intercession “for the stranger who is not of this people; 25 for such as groan under oppression, “who sow and reap not, who tread the olive but are not anointed with the oil.” 26 For such as are wasted by war, by pestilence, by famine; and especially for them, who sit in darkness and in the region of the shadow of death. Such expressions of benevolence become our highly favoured condition, and such devout sacrifices are acceptable with God.

It is not to be doubted but that united America has yet to exhibit an interesting character, and act an important part on the theatre of the world. The womb of futurity conceals the secret, whether she shall imitate the vices and experience the catastrophe of other nations, or whether her manhood and old age shall be as singular and unique, as her birth and youth. We may be ready to wish that Providence would permit us to become a great nation; but the spirit of Christian patriotism rather dictates another petition, that we may be a good nation, and that happy people whose God is the Lord. May not united America ever vie in magnificence and splendor ancient Rome, and after stretching the arms of her power from one end of the world to the other, pillaging mankind and becoming rich with spoil, suffer the distress and ruin, which she shall have inflicted, bow to the hardy courage of some barbarous Alaric, and sink under the dissolving influences of effeminacy and corruption. But may we be that virtuous people against which there is “no enchantment,” against which the heathen may rage and the kings of the earth set themselves in vain.

“Blessed is the nation which walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, whose delight is in the law of the Lord. It shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of waters, its leaf shall not wither, and whatsoever it doth shall prosper.”

Note. A few paragraphs of the preceding discourse were omitted in the delivery, through want of time.

9.I could wish that myself were accursed from Christ.—This passage has been variously interpreted. By some the most literal construction is preferred, and the writer is understood to say, that he was willing even to postpone his own salvation, if it could be the means of saving his countrymen, by atoning for their sins. By others, he is supposed to describe his own former character, (I did wish myself accursed) the recollection of which made him more solicitous for the conversion and safety of his kinsmen, as it created a more lively feeling of their error and danger.—Another interpretation may be grounded on the ambiguity of the original term, rendered accursed, which may properly be used to express an honourable oblation. The meaning then is, that the apostle wished to have been deputed from Christ an apostle to the Jews, rather than to the Gentiles. From patriotic feelings, he would prefer to exercise the functions of his apostleship with his kinsmen and brethren. Whichever construction be adopted, the idea of love to country in the doubtful sentence under consideration concurs with the whole passage vigorously to express the sentiment of patriotism.

10.Mr. J. Q. Adams’ Ann. Ora. Plymouth.

15.President Washington’s Address on retiring from public life.

16.Nothing is intended by this remark unfavourable or disrespectful to those individuals or associations, whose object is the dissemination of useful tracts. It is believed their designs are pure, and that their liberal exertions in this way have produced many good effects. It is however to be wished, that the books circulated should not contain dogmatic decisions on points of doctrine of a doubtful nature. The prefaces or appendixes subjoined should not be designed to make the common reader lay a stress upon particular controverted ideas and phrases, which many serious and judicious ministers decline introducing into their course of weekly instructions. We may also ask, is it not time that our country should produce authors upon common subjects, who can treat them with more conformity to the feelings and language of the place and time?

18.The following general observations in Neeker’s work on the Influence of Religious Opinions, with many others in the same volume, deserve to be universally known and considered. “I cannot, I avow, without disgust, and even horror, conceive the absurd notion of a political society, destitute of that governing motive afforded by religion, and restrained only by a pretended connexion of their private interest with the general.” “It is at the tribunal of his own conscience, that a man can be interrogated about a number of actions and intentions, which escape the inspection of government. Let us beware of overturning the authority of a judge so active and enlightened. Let us beware of weakening it voluntarily; and let us not be so imprudent as to repose only on social discipline. I will even venture to say, that the power of conscience is perhaps still more necessary in the age we live in, than in any of the preceding. Though society no longer presents us with a view of those vices and crimes, which shock us by their deformity; yet licentiousness of morals and refinement of manners have almost imperceptibly blended good and evil, vice and decency, falsehood and truth, selfishness and magnanimity. It is more important than ever to oppose to this secret depravity an interior authority, which pries into the mysterious windings of disguise, and whose action may be as penetrating, as our dissimulation seems artful and well contrived.”

19. In this respectful mention of Benjamin Thompson, we have particularly in view his meritorious services to the poor of Munich.

24. “It is said of Aristides, that he would never consent to any injustice to oblige his friends. He declared that a good citizen should place his whole strength and security in advising and doing what is just and right. In the changes and fluctuations of the government his firmness was wonderful. Neither elated with honours, nor discomposed with ill success, he went on in a moderate and steady manner, not looking so much to the reward either of honour or profit, as persuaded that his country had a claim to his services. When the following verses were repeated on the stage, “To be and not to seem in this man’s maxim; His mind reposes on its proper wisdom, And wants no other praise—the eyes of the people were fixed on Aristides as the man to whom this encomium was most applicable.”