A Plea for the Militia System

in A

DISCOURSE

Delivered Before the

Ancient and Honorable

Artillery Company

on Its

197th ANNIVERSARY

June 1, 1835

By J.G. Palfrey, D.D.

Professor in the University of Cambridge

Published by the Company’s Request

Boston:

Dutton and Wentworth, Printers

DISCOURSE

Apocalypse III.2.

Be watchful; and strengthen the things which remain, that are ready to die.

One hundred and ninety-eight years ago, my hearers, (the colony of Massachusetts Bay then consisting of only fifteen towns,) the associated founders of the military company, by whose invitation we are to-day assembled, petitioned the governor and council for a charter. At first it was denied; the council, as the journal of that admirable chief magistrate, the ancestor of the company’s present commander, records, considering from the example of the Praetorian band among the romans, and Templars in Europe, how dangerous it might be to erect a standing authority of military men, which might easily in time over throw the civil power? By the following year, however, the apprehension had subsided, and the application found more favor; and on the first Monday of June, 1638, the first election of officers took place under a charter, containing, among other peculiar privileges, the provision, that, on the days of the company’s monthly trainings, no ordinary town- meetings should be held within this part of the jurisdiction; a singular testimony to the consequence of men, without whose presence municipal business could not be safely transacted. The object of the institution is set forth in terms of the preamble, which recites, that divers gentlemen and others, out of their care of the public weal and safety, by the advancement of the military art, and exercise of arms, have desired license of the court, to join themselves in one company. It was designed to be a school of officers; and actually embraced on its first roll the names of all the commissioned officers of the train-bands of the neighboring towns. These were voluntary associations, which constituted the whole martial force of the colony, till the organization of the militia in four regiments, corresponding to the four counties, in 1644.

The officers of the militia, like those of the primitive train-bands, continued generally to qualify themselves for their commands, by service in the ranks of the Ancient and Honorable Company. It was this militia of Massachusetts victoriously through the most gloomy period she ever saw, that of the Indian wars, at the close of the seventeenth century; and which humbled the French power in this western world before that of England, in the war of 1753 to 17561. It was the militia of Massachusetts, which, after standing alone the first shock of the revolutionary contest, furnished one soldier in every four, through the war which followed, to the continental army; and which, (to speak of a less conspicuous service, yet one on which the salvation of the commonwealth, and of the sovereignty of cis-atlantic law depended,) crushed, in 1786, the insurrection in the western counties.

When, in the more recent war, an exasperated enemy, its vast resources just let loose from the fields of continental Europe, was hovering on our coast, and the national forces were withdrawn to the inland frontier, so complete was the militia organization, that, at twenty hours’ notice, companies fully equipped and provisioned, had in several instances reached, from twenty miles’ distance, the point of alarm; and they garrisoned satisfactorily the line of maritime forts, which the national troops had abandoned, thus securing the ports and cities.

But, after the time of danger had past, the militia began to be affected by other influences. The decline of its own efficiency, along with the course which public opinion took in relation to it, is to be seen in the history of laws, thenceforward from time to time enacted. In 1823, the three legal company trainings in a year, in addition to the annual spring inspection, and autumnal review, were reduced to one. In 1830, all persons, between the ages of thirty and forty-five, were exempted from military service; a measure of course attended by a vast reduction of numbers, and a great inconvenience, (in religion thinly people,) in collecting sufficient numbers for purposes of discipline. And, in 1834, all parades, independent of the annual inspection of arms, were abolished, except for volunteer companies; and the members of these were authorized to withdraw on giving six months’ notice.

The consequence of these measures has been probably much more destructive to the militia system, than their advocates anticipated; certainly more speedily destructive than their opponents fore-told. The volunteer companies, kept together hitherto by an ambition in their members to do better than others what all were compelled at any rate to do, and required now, when collected in masses, to assemble at points distant from one another, are, far and near, rapidly disbanding; and the public pecuniary bounty, (though it has been raised this very year,) being what a Massachusetts citizen is unused to taking, for preparing to defend his own fireside and freedom, apparently does absolutely nothing to obstruct the tendency. Officers, elected to the highest posts, finding no attraction in a command, which is only not nominal when it calls for some obnoxious exercise of authority, are constantly declining to serve at all, or soliciting to be discharged. And into such contempt, under such circumstances, has the institution fallen, that it was actually found necessary to enact a law, at the last session of the General Court, authorizing the commander in chief to withhold commissions from “idiots, lunatics, common drunks, vagabonds, paupers, and persons convicted of infamous crimes, when elected to militia commands; several instances of such elections being known to have occurred.

Being brought into this place, by the flattering indulgence of this company, but without any expectation or any wish of my own, I would use the opportunity, in endeavoring to say a word, (which I hope and pray may be spoken in the spirit, becoming a well-intentioned citizen, and a Christian minister,) in behalf of the once efficient and admired, now apparently expiring militia system of Massachusetts. And if I argue against the fitness of existing laws, I offer no disrespect to the law-making power. The system is all unsettled. To a great extent it is acknowledged to be so. Should I exaggerate much, if I alleged that there is a universal conviction, that, if the militia system is not to be sustained, some existing burdens may and should be dispensed with; and that if it is to be sustained, the existing laws are altogether insufficient?—and I do not content myself with saying, that the Federal Constitution, the paramount law of the land, requires that it be sustained, because the case will be more satisfactorily rested on its own merits; though I confess I do not see, how anyone can take the oath of office to support that Constitution, who means to use his authority to the sacrifice of the militia system, or to neglect even to afford it his positive support.

I perceive no more convenient way of approaching the point at which I aim, than by adverting to some of the causes, which may have led to encroachments upon the ancient organization. When I have asked for these, I have sometimes been referred to the progress of principles of international peace, as indicated and extended by the formation of Peace Societies. With some opportunities of judging, (not perhaps, however, such as would authorize me to speak with confidence,) I believe that this cause has had no very considerable operation. I believe it, and I hope it. I hope it, as a friend to the militia system, against which I should be distressed to think, that the influence of a large body of active and philanthropic men as to be enlisted, on the ground of an erroneous abstract principle; the militia system, the trustworthy instrument of defensive war, and the safe substitute for that institution of standing armies, whose tendencies are essentially offensive. I hope it, as a friend to Peace Societies, which could hardly be more discredited or checked, than by identification with them of the theory of the unlawfulness of defensive war. I am no skeptic respecting either the excellence or the practicability of that enterprise, in which these societies have been engaged. When I mark the wide action of the renovated power of Christianity, to control those bad actions from which almost all wars, (shall I say, all wars, if traced to the encroaching party?) have proceeded; the juster style of reasoning, which to a great extent prevails, on questions both of moral right and of public interest; the multiplied relations of commercial and literary, yes, and of religious intercourse, to which war brings interruption and disturbance; and the increased and increasing power of the people, whose interest offensive war can never be;–when I turn to facts, and observe what a constantly progressive triumph of humanity there has been, upon the whole, in amelioration of the practices of war, and what a revolution of sentiment has been witnessed, even within the century, in respect to usages hardly before suspected, such, for instance, as that of the private pillage, (under public commission, but for private gain,) of property upon the ocean,–a revolution so great, that now, I will not say a conscientious man, but a man who had a character to keep, could hardly, I suppose, be found to touch the unclean thing, and many a one, with no fastidious sensibility either, would well-nigh as soon suffer himself to be called a pirate, as to be called a privateers man;–when I remember, that the scheme of a court of nation has, in these last years, actually been put in force, if under circumstances going to impair the worth of the example, through the exhibition of selfish designs, still in a way perfectly to illustrate the capacity of the plan to be prosecuted to ends of beneficence and justice, when the point of honor should be deficiently raised by mutual pledges and a sense of judicial responsibility;– and when I advert o such instances, as that of our own last controversy with England, submitted to the arbitration of an inferior mutually friendly power, rather than to the chance of arms, simply because the parties were wise enough to see, that the morals, and dignity, and interests of both, dictated this for the reasonable course; when I weigh these and other truths and facts, most important in the connection, I see, my hearers, ample, overflowing encouragement for labors designed to teach the nations, that they ought, and that they can, and they had better, live together as brethren.

But, if any go further, and say, that life, and children, and liberty, and country, are never to be forcibly defended against unlawful violence, I find myself obliged to diverge from the path of such. I must do it, following my own convictions of duty as a reasonable and a Christian man. In my view, they read very erroneously the book of God’s will, equally as it is written on fleshly tables of the heart, and on the pages of recorded revelation. I am tempted to ask myself have they weighed that whereof they affirm. Does their imagination represent to them no extreme case, (–for let it be observed, the very question they raise, is on extreme cases, no other,–) in which they would think it an unlawful abandonment of duty, not to resist, to the last violence, the violent hand? Let them answer that inquiry to their own consciences. I find only one way of answering it to mine. I make no question here of rights of self-defence; of privilege, and the like. I know no privilege to be brought into such considerations, except that of doing the will of God, our Maker and our Judge, to the best of our knowledge and the utmost of our power. The life he gave me is his trust resting with me. I am bound to use it for his glory, in the promotions of the objects for which he made me to live. As different circumstances, the basis of different obligations, dictate, I may so use it by keeping or by resigning it. The one or the other may become my duty; and whichever becomes my duty, that I am cheerfully to do. In God’s service, (that is, in the way of acting my own allotted part,) I must be as ready to carry my life to the scaffold or the stake, as to the field of battle; so I must be as ready to give my own life or that of others on the battle-field, as my own on the scaffold or at the stake. Let each determine the question, for his own government. But I must be further advised, before I perceive how a good hope for eternity could be reasonably enjoyed upon a death-bed, by him, who, in the one case, any one than in the other, had shrunk from the terrible appeal.

Am I told, however, that our Lord himself said, ‘Resist not evil?’ He did say it; and let it be observed, that the words prohibit , not sanguinary resistance, not forcible or restraining resistance, but all resistance, all obstructing of the evil-doer, whatsoever. Taken then from an unlimited rule of universal action, they would no more directly, and absolutely, and unequivocally, prohibit military defense, than they would forbid the public officer to hold back the incendiary’s hands while he applied the match to a granary, or charge the keeper to desist, who was binding a madman.—I cannot go here into a question of scriptural interpretation. But does this remark suggest the propriety of inquiring, whether the precept in question was not intended to bear upon the course of persons, commissioned under peculiar circumstance, to a peculiar duty, which duty, under those circumstances, the course thus prescribed was the appropriate ne to perform? The text connecting itself, so far, with that other in the same discourse, where the same persons seem to be directed to have no more care for their sustenance, than did the fowls of the air and the lilies of the field, and with the direction to the disciples to take no money for the journey, nor scrip, nor staff, nor so much as a change of garments. Arrangements for personal accommodation would obstruct the object. Therefore, these were to be forborne, and God would supply the want. Resistance on the part of the early preachers of our religion would have been unavailing. It would also have prematurely exasperated against them an exterminating power. It would have lost them the hearing, which it was their special business to obtain. Non-resistance, under their peculiar circumstances, was their safety and strength. So it may, no doubt, under the like, or under different circumstances, be ours; and then it will also become our duty. But to make the precept quoted sustain the inference sometimes deduced, one must first show, either that it was designed for universal application, or else that there is a similarity between the case which it contemplated, and that to which it is now applied, as to give it an equal applicability to both. And in either result, I think, certainly in the former, the precept will then require to be taken in the large comprehensiveness at which I just now hinted; a fact which seems to have been wholly overlooked.

When it is further urged, that non-resistance has, in instances, which are appealed to, actually proved the most effectual protection, I suppose that no inference can be safely drawn from an induction so exceedingly limited as has been made, except of a truth which needs little confirmation, however much more consideration It may deserve; namely, that a kind and inoffensive deportment, is, to the extent that other causes allow it to operate, a most conciliating quality; to which I would add, that it may be not the less, but the more so, when it is known that he, who practices it, will defend himself from outrage in the last resort. Surely no one would undertake to argue, on such grounds, I the face of all the history of man that the inoffensive are exposed to no wrong or that cupidity and brutality will be infallibly disarmed, as often as they can be indulged without opposition or hazard.—But I must leave this subject. To undertake to pursue its discussion, to a length in any degree proportioned to the importance communicated to it by the excellent character of some, whose theory here I told to be all wrong, would be to exclude for today every other topic. If their endeavor seems to us, in some views, as mischievous as it is honest, this should not make us impatient of it, both because of the motive by which it is impelled, and because the whole history of man’s progress is that of a struggling of truth towards its rightful place of sway, though a throng of opposing, and mutually opposing errors. The remarks which follow I must be content to address to such, as admit the lawfulness of defensive military action.

Again; I have heard it said that the friends of temperance have exerted a strong influence, adverse to the integrity of the militia system. It may be so; but having, till recently, had a somewhat intimate acquaintance with the progress of measures and of opinions touching this subject, I do not recollect to have seen an argument of the kind supposed. It was again and again stated, it is true, that, at the numerous meetings which military parades occasioned, mournful exhibitions of intemperance were made. But the same thing was affirmed of all occasions which brought crowds together, however needful, and (must I say it?) however sacred. Intemperance was to a melancholy extent the habit of the country, and, being so, of course painful manifestations of it were made, as often as numbers of men were for any reason assembled. Am I bidden to ask the militia officer, what he has witnessed disgraceful in this way, at the parade and the review? I will put that question; for all facts are wanted, which will yield to avert an unspeakable calamity, and expose a crying sin. But I must go further than to the militia man, and inquire of the judge, and the municipal officer, yes, and the minister, what they have witnessed of the same kind, among the multitudes collected by the court-week, and the town-meeting, and the ordination-day. Will you shut up the courts then? Will you interdict the municipal assemblies? Will you cease to give a ministry to the churches? No; wise men do not so leap to a conclusion. The evil will disappear from crowds of all kinds, and those assembled by one occasion as well as by another, in proportion as the taste for it are subdued in the individuals who compose those crowds ; and in the meantime, let, of course, the advancing reform be aided, by all such safe and practical laws, as may prevent the excitement of crowds from being accompanied with peculiar temptations to excess. Our legislation has, in fact, been more sensitive on this subject in relation to the militia, than to any other public institution; a law having been passed, five years ago, to prohibit those entertainments of militia electors, by their officers, which had up to that time been practiced. In the present state of enlightened opinion on this matter, what the Commonwealth forbears to do, in the way of restraint and security, may be left with strong hope to the vigilance of the municipal corporations. When the authorities of the city, with its more mixed population, have been able to expel spirituous liquor, even from the theatres, (at the cost, perhaps, of some odium to those who first moved in the measure, but of nothing worse,) I greatly err, if the ‘village Hampdens’ are found so far in the rear of the reform, as to endure its polluting presence on the militia muster grounds. But the truth is, that the mountain of the Temperance reformation stands too strong, to admit of any hazard being incurred in its support, of injury to nay of the great institutions of the country. It is doing grievous injustice to that enterprise, to suppose it is so weak as to need to ask a sacrifice in its behalf, at the hands of anything else that is good.

But I am persuaded that disaffection to the militia system, considered as a wide-spread sentiment among the people, is to be traced to quite a different cause from such as have now been touched upon. It is, if I mistake not, among the earliest developments of a principle, from which many of our most important institutions may ultimately prove to be equally in danger. As such, I call on good citizens to watch it. I refer to an imperfect perception on the part of those, for whose benefit our political system was framed, and at whose mercy it all lies, of the permanent worth of arrangements may cost, I am persuaded that to this it is, beyond almost everything else, that the solicitude of the American patriot requires to be directed. Our institutions, the fruit of great political experience and forecast, were most wisely and honestly devised, to secure the greatest good of the greatest number. Make the people see, that they have that character, that tendency, that fitness,, and the people are sufficiently their own and one another’s friends, to bear cheerfully all burdens incident to their support. But a political system, embracing the necessary safe-guards to law and liberty, (that pair, so strictly wedded, that one directly follows the other to the grave,) is necessarily somewhat complicated, its parts requiring careful reflection to discern all their use. And the object of some of its most onerous provisions may be the prevention of evils, which, while, occurring, they would be so great, that they demand meanwhile the most scrupulous precautions, are yet not apparent except to the practiced or jealous eye, perhaps remote, incidental, seemingly or really improbable,–I should be ready to suppose, for the argument’s sake merely possible; and such provisions are of course always liable to become distasteful to all but the reflecting, as often as their burdens press. When our system was proposed for adoption, men whose minds comprehended and could simplify the whole scheme, took pains to cause the use of every portion of it to be understood. The American people understood it, and perceived its excellence the more clearly from recent severe experience of evils, whose recurrence they saw it was well devised to prevent; and understanding, they cordially adopted it. But I greatly fear, that the want of perpetually repeated expositions of the principles of our government is already beginning to be felt; and as soon as from this cause, ignorance of them, or inattention to them, shall come extensively to prevail, everything we ought to hold dearest is thenceforward at the mercy of the mistake or the discontent of the hour. A present inconvenience is felt, and the reason why it should be borne, as the reasonable and the necessary price of something precious, is overlooked, and honest opposition is tempted. A judge decides a case, as we think, wrongly, and we indignant that we cannot command the advantage of an annual election of judges, to supersede him next year by a better man; forgetting what a blessed boon the constitution has secured to us, as it has secured to all, in giving to us in our time of innocent peril, an impartial judge; a judge so impartial, that he would not let a hair of our head be touched, though our head should be called for by a whole clamorous community; a judge, so impartial as he could not be, if opposition , at any time, to the will of an uninformed and excited majority, would be a forfeiture to him of the means of living. We are impatient that a national measure, which e think good, should be checked by the action of the more permanent legislative branch, and we complain that any constitutional hindrance should exist to the instantaneous consummation of what we call the people’s will; forgetting what safety must unavoidably be often found in the suspension of an excitement, which, indulged, it might be self-ruinous, and in the effectual expression of a judgment, which being more deliberate and responsible, may be expected to prove more wise. So the interruption, and fatigue, and expensiveness of militia duty are felt as an annoyance. Show us, it is said; an enemy to repulse, or a usurper to demolish, or an insurrection to quell, and then we see why we should submit to it. But we dwell among our own people. No foreign hostility molests or makes us afraid. We have no ambitious ruler, or factious citizen, who seems to be entertaining a design against our liberties; and such is the prevailing sense of the majesty of law, that the civic force seems ample to secure to it respect and efficacy. And, under such circumstances, the annoyance does appear to us to be without a sufficient corresponding benefit.—Accordingly, the young man, who is subject to do militia duty, is dissatisfied to make the sacrifice of his day’s work or his day’s leisure. The old man, who is not subject to it, is dissatisfied to have his work left on his own hands; the farmer missing his sons and his laborers, the mechanic his journeymen, the merchant his clerks. The rich complain of the cost of ammunition, carried to the town accounts. They are told, to reconcile them, that the militia charge is an outlay for the security of the property of the rich; and so it is, for it is for the maintenance of liberty and law, and these again protect property, just as they protect life. And then the poor, hearing the rich thus argued with, remonstrate on their part, ‘if this kind of work is to protect property of the rich, let the rich do it, or pay to have it done:’ forgetting that the argument would apply equally well to the interruption and trouble of their attendance at the town-meetings, to see the election of good magistrates. The citizen, high or low, whosoever he be, goes as much to the town-meeting as he goes to the militia parade-ground, to secure the property of the rich; but it is by doing what will at the same time protect the day’s wages of the laborer, and what, while it protects property, will at the same time protect liberty and life,–the liberty and life of both, rich and poor together.—the argument forgets another thing. May I venture to state it, so revolting is the consequence? ‘Let the rich do the militia service,” it is said, “if they wish it done.’ Abandon then, the arms and the discipline to them, and create at once an aristocratic standing army. Are we ready to take such counsel? ‘Let the rich pay for the service, if the service is wanted.’ That is, let the rich have an army in their pay. Does the spirit of Massachusetts brook that proposal?—So easily my hears, do stimulating addresses to the selfish passions

of the people, resolve themselves into applications to them to desert their own cause.

After the war of independence, that militia system, the wreck of which still survives, (which, I will not say in the words of the context, has ‘yet a name to live, but is dead,’) was incorporated by our ancestors into our institutions, because they hoped that they were establishing aa reign of liberty and law, and the experience of the world had shown them , that this must be maintained, if at all, by a sufficient military force, or, better, by the show of a sufficient military force, to discourage or defeat aggression; and they conceived that to none could the defense of liberty and law be so safely entrusted, as to those who were personally interested for their preservation ; and they probably would have said, that in their thought, the sacrifice of some days in every week, instead of some days in every year, (had that been needful to obtain sufficient security,) would have been a cheap price in such a purchase. If we do not like the arrangement, what will we have instead? Will we have a large standing army? My hearers, you would not listen to me, if I should undertake to argue that question. There is no institution, of which you are so irreconcilably suspicious. You know, that where that exists, despotism exists; the despotism of the movers of the colossal and unthinking machine, whether one, or few, or many. You cannot endure the thought of having those, in any strength, within your borders, whose sympathies together are the sympathies of a camp, whose will is the unexamined will of their commander, whose trade id force, who are essentially trained to despotic principles by the habit on their own part of implicit obedience to authority, and whose elaborate discipline enables them, under some circumstances, to cope with a large preponderance of numbers, and put on them the fetters which they wear themselves.

Will we then look to a voluntarily organized force to give such protection to the country, and such support to the laws, as emergencies may require? If it were not that I conceive, that, under existing circumstances, such a force is little likely to be collected to any large amount, I should tremble to think of what our recent laws have done to bring about such an arrangement. Already the Commonwealth’s militia at large is essentially disbanded. What remains are the volunteer companies. “A select militia,’ said John Adams ‘will soon become a standing army.’ Here is already that select militia. It is further composed, (that is, in the contemplation of the law, I cannot say whether as yet in practice,) of mercenary troops. Their pay has been raised within the year, and may be raised again and again, till it shall be an effectual lure to recruits. Moreover, there is this great peculiarity in this paid force that it is offered by itself, with the exception only of the highest posts, which are filled by the government. The law clearly points to a monopoly of military practice and skill, in a self –constituted and self-officered body. I do not believe, I repeat, that the system is permanent; else I should say, that it could not be wisely viewed without extreme alarm. I content myself with asking, whether its tendencies are not most distinctly anti-republican. Could the people of this Commonwealth long see, without irrepressible uneasiness, a body of troops among them, collected by mutual pledges, and permitted and encouraged to bring themselves to the highest state of discipline and military sufficiency, while at the same time the body of the people were abandoning even the inferior discipline, in which a partial security would , in case of need, be found, and under the name of leaving to others the trouble, were in act doing a different thing, that is, leaving to others the power? If the scheme should have time allowed to develop its tendencies, I make no question that reason would be found for reviving, (and on more serious grounds,) the apprehension of our primitive magistrates, when they scrupled about the incorporation of this company, recollecting the instances of the Praetorian band in Rome, and the Templars in feudal Europe.

If we take none of these risks, what will we do? Will we go without any array of physical force, for our institutions to rest upon in the last resort? We may say this, and we may hope that we shall be able to do it harmlessly, till a painful and costly experience comes to undeceive us. By the ordination of Providence, vigilance is the price to be paid for safely, which is a pearl of great price. Precaution and peril take each other’s places, just as surely as the sun’s departure is followed by night. We say, we see no danger. It is because we have seen precautions, by which the element s of danger were over-awed, and checked from springing into actual being. The energetic militia movement in Shay’s rebellion, for instance, was a solemn lesson read by the Constitution and the law, not to be forgotten while that generation lasted. Let the precautions disappear, and as certainly as human nature is not as yet completely reformed, the danger, in some or in all of its forms, will reappear. And when this shall befall, we shall have at last to take the steps which we shall then no longer be able to doubt that it demands, and to take them then not only under the conviction, that they would have been taken more effectually, if taken more seasonable resort to them would probably have saved us all the various injury, resulting from danger which has at length arisen. And it is under the most profound and anxious conviction of this, that I, for one, desire to see the strength of Massachusetts all ready to provide, in any emergency, for the safety of Massachusetts, under the direction of her wisdom, as exerted and expressed through the constitutional organs. I would have it already to apply to a foreign assailant, at every point of her border, ‘hitherto mayest thou come, but no further,’ no, no further than to that sacred line. I would have it prepared, in any time of actual or threatened commotion which may come, to take that attitude of dignity, forbearance, and gravity, but decision, which only a well-grounded self-reliance for the possession of means to meet consequences, will sustain; and to speak one of those loud voices of command, for the integrity of this union, which may be needed, the Omniscient only knows how soon. I would have the militia of the country in a condition to make the usurpation of arbitrary power so impossible, that the very thought may not reach, I will not say its birth, but so much as its rude conception, in any ambitious bosom. I would not care so much to urge, that that physical force, whose preventive or remedial uses are so indispensable to the existence of a state, should be embodied in a militia, rather than in a mercenary army, because it is a much less expensive security against danger of foreign invasion; though certain it is, that, while its pecuniary burden is not very seriously felt, military establishments have always been a ,most oppressive tax upon military governments, and a most multitudinous and exhausting host that must be, which would cover our extended frontier. I would not even chiefly insist, that, while a militia costs less than a very insignificant standing force, it is actually more effective, for purposes of defense of a country of geographical position like ours, than the largest standing army which the treasury of the most thriving country could support; more effective, unquestionably, their comparative numbers considered, whatever weight may be thought, by one or another, to belong to the facts, that the militia-man has that intimate acquaintance with the natural features of the region he is defending, which is often worth books full of science, and that it is his own hearth and altar that the militia man defends;- how effective, let Concord and Bunker Hill bear witness, though even these are not fair examples, for the aggressor of that day, in consequence in past relations of the country, had first obtained peaceable foothold on the shore. In an argument so practical, I would not even put prominently forward the sensible principles of the case, and press the truth, (or what I hold for it,) that a militia force is the reasonable, as well as the cheap defense of nations; that the ancient, superseded theory on the subject, was the true one; that, with some necessary exceptions, military service is of that nature,, that it ought to be done by men for themselves; that it ought not to be delegated; and especially, that it is a proper tribute to freedom, to defend her by a freeman’s , and not a mercenary’s arm. Upon the thought, that a militia organization is the strong arm of only defensive war, I should be tempted, for reasons of philanthropy, to dwell;– so rooted and quick is my conviction, that an offensive war is a measure only approached in its wickedness by its folly; that there is no more cruel plague of men, and no more outrageous and high-handed offense against their Maker; and that, in a standing army, there are strong and ever-active tendencies to offensive war, while a militia, at least that of a prosperous country, is hardly capable of being used for purposes of offense;–hardly capable, except in one of those rare contingencies, in which there arises reason for it to do violence to all its habits, to strike a sudden blow abroad, so as to anticipate and foreclose a severer struggle at home. But I would, at all events, implore the patriot to reflect, that a sufficient physical force is indispensable to sustain, in the Last resort, the empire of liberty and law, while the knowledge of its having been provided will afford the best attainable security against their ever being brought to an arbitration of blood; and that, on the other hand, the only force not dangerous to liberty and law, is the force of the legally-armed free-citizen. I would beseech him to remember, that he should be attentive to sustain a sufficient militia system, because a militia force is the only large force that a free people can trust for defense against foreign assault, and because it is a force, which, giving it such organization as to do the behests of law, a free people must trust, if they mean to be secure against usurpation and against anarchy. And if this be so, the people, who, because of any attending unavoidable inconvenience, will be discouraged from keeping it up, are as unworthy of the liberties they enjoy, as they are actually in danger of losing them.

Of the liberties they enjoy, I say. And that is the word, rather than the liberties they possess. For possession implies something of a power to keep, and that of which I am speaking might, under the circumstances supposed, prove to be no more than a possession which was dreamed of. Do you tell me again, that no danger is visible? You only say what alarms me most. I would rather, for security’s sake, that you would use almost any other language. I hold, that there always is public danger, as often as the persuasion exists that there is none. And if there is no present danger, has it never come upon us, and come suddenly? And have there been no other times, when it would have possessed us, but that we knew we had that, wherewith we should oppress it? Can none of us remember the time, when, rebellion being formally menaced by the temporary authorities of a sister state, once of different fame, we thought that patriotism might have to stand to its arms, at least till the vain but self-exciting insult to the majesty of union should be abashed?—How long is it, since some people thought, that there were only two differences between the head of this nation on the one hand, and Cromwell and Napoleon, at a certain crisis of their rise, on the other;–the one difference being, that the latter had already a subservient army, while the former could raise one with a word;–the other difference, that in the way of the former there would still stand one million three hundred thousand (enrolled at least, and to a great extent, armed and disciplined) militia-men, the great majority of whom , whatever might be their personal party-predilections, had no supreme wish but their country’s good? I do not say, that the persons, who entertained that thought were right. I do not stand here, to take any ground on questions of party divisions. I allow, for the purposes of this argument, that the head of this nation is as pure a lover of his country, as his country’s annals name. Still I say, God forbid that the time should come, for the liberties of this nation to depend on the good intentions of any man. Were he a patriot as irreproachable, as incapable of being suspected, as George Washington, (–and now I have gone to the furthest limit of language,–) still I cannot consent to hold my freedom by no better tenure, than that of his honest views. Freedom? No; that is not then the word; it is sufferance. Only satisfy me, that there was not physical organized power to have scattered his retainers to the four winds, and given his dishonored limbs to a gibbet, the hour that he should have been solemnly convicted of arming them against his country’s liberties, and I ask no more, to own myself his slave. Let him make me feel the iron or the thong, a little earlier or a little later; and whether earlier or later, it matters not mush; but the time is then for his own choosing. No danger, to make it necessary to keep up the force, which danger, if it came, might make desirable! Why, how long is it since the twelfth and thirteenth nights of August 1834? Boston, on those nights, was a well-appointed garrison, commanded by those safe and trusty officers, the sheriff and the mayor; and because the Lord kept the city with his militia-men, the watchmen did not wake in vain. Did anybody foresee, on the eleventh day of August, that, in twenty-four hours, we should be in such an uproar? As much,–as much, and no more,–as we expect that the same scene will be re-enacted on the second day of June, 1835. Are the same elements of disturbance all expelled.—the same elements, and the like, and different, so that we may be sure that a similar scene will never be repeated? Or to quell a domestic riot or insurrection, when it occurs, or in view of the possibility of their recurrence, will Massachusetts be content in relying on doing what Virginia has lately done, that is, inviting in Federal troops to quell them? Will she consent to do this, I ask, till she is unable to do better? If she will, I have misconstrued her history. I have not learned the alphabet of her character.

But, my hearers, I forebear from this vast theme, for I ought to find place, before I close, to say a few words regarding another aspect of the subject;–a few words, and modestly, for the subject, in that aspect, is under the cognizance of much wiser heads than mine. If a well-regulated be, what the constitution declares it, ‘necessary to the security of a free state,’ a freeman’s and a patriot’s wish will be to know, and knowing, to do, as far as in him lies, what, under existing circumstances, is requisite, for its stability, credit, and prosperity. Without presuming to prejudge a case, submitted to such competent discretion, I would however venture to anticipate, that three or four points will be objects of especial notice.

I presume, that, while the leading object will be, on the one hand, to remove unnecessary burdens, and, on the other, to secure a sufficient enrolment, equipment, organization, and discipline, care will be taken to restore to officers an actual command; since, without good officers, there cannot be good soldiers, nor means of using them, if they could exist; and officers cannot be expected to find attraction in posts which bestow only a title and some obnoxious trouble, without authority to advance the object professed to have been undertaken; so that, unless this feature of the system be reformed, the only apparent remaining resource must be, to compel officers to serve, under a penalty, as jurymen are now compelled; a scheme certainly liable to great objections.

I suppose, that another step may be, greatly to reduce the number of legal grounds of exemption from military service, a number now so large as to occasion much dissatisfaction and discouragement. I am almost ready to say, (at least, as to the general theory of the case, whatever modification minor considerations might require,) that there should be no exemptions, till the prescribed term of service has been finished, except for those, who, at the hour when they would be rendering it, are actually employed in some other duty, in which the individual, then exempted, may better serve the state. Military service is, on all just grounds of estimating it, personal service. It is not what one can fitly or reasonably do by proxy. It is a stern duty, which one must be content to perform for himself. I could as honorably, (higher reasons for not interfering,) hire another to plunge into the water, in my place, to rescue my child, as to go to the field, while I remain behind, to defend my country for me. I cannot serve in two ways at once; and therefore, when I am sitting on the bench of justice, or in the hall of legislation, I must needs be excused from the camp. But the permanent exemption of any classes of men, as far as it proceeded from, or went to instill the idea that their occupations were too dignified, or too sacred, to be consistent with military service,–that a patriot soldier’s duty was not the duty of a grave or a holy man,–would not only be utterly indefensible as to its grounds, but also it would be either greatly dispiriting, or else greatly demoralizing, to those who were left to fill the ranks.

I suppose that the great outrage of electing notoriously unworthy persons to commands will not be dealt with by the law, any further than to provide some satisfactory way of ascertaining the character of such elections, so as to make them invalid. It is impossible that the practice, (but I hope that a practice it has nowhere yet become,) can live under the indignant rebuke of an honest public sentiment. The penalty of disfranchisement of such faithless electors would be in theory the resource. But disfranchisement for wanton abuse of the prerogative of suffrage is a penalty not known to our laws, and with reason, since the offense would be so difficult to prove, and the application of the remedy would open a way for the inroad of corruption of another kind. Else disfranchisement would be the natural and just resource; for the corrupt voter, in a militia election, has pronounced himself unfit to be trusted with a citizen’s power. He is one, against whose vote the government in all its departments, the community in all its interests, his neighbors in all their relations, is concerned to have full protection. Mark the company which has done this thing. I know them not; but I know, that, (except that it were done under the temporary excitement of some passion or folly, by which all of us are liable to be misled,) the roll of that company, on whatever plain of the pilgrims’ clearing its musters, is a rag of shame. It holds the names of those, who are not suitable associates for honest men; for, if the throwing of a vote to any other end, than the election of the best man, is a citizen’s perfidy, what name is there for a vote thrown with the intent to elect the worst? Mark the individual who does it, if he is so reckless as to commit himself to your knowledge; mark him for one who is ready to sell his vote, who is in a way to be ready to sell his country and himself, for the gold, shall I say? No, for the copper, of France, or England, or Portugal, or Haiti.—and after law shall have finished its discreet and righteous work, still there will remain much to be done, in the way of encouragement, as well as of correction, which law can of its nature only partially accomplish, and which public opinion, in the militia man, and in every citizen, must be enlightened and excited to undertake, to the end that officers and soldiers, seeing more clearly the honorableness and dignity of the service, may be more prompt to serve, and more interested to excel. The majestic principles, on which the institution rests, must be made better understood, and the springs of the patriotic spirit, which is its life, be touched by master hands. A militia parade must not be suffered to pass in any mind, for a mere holiday exhibition; it must be seen for what it is, a great and happy people’s preparation for the maintenance of what makes it great and happy. Never should the idea have been allowed, for want of care, to establish itself, that the militia meetings were mere entertainments. No wonder, that those who had gone so far, as thus to regard them, went so much further, soon, as to regard them as idle entertainments. Yet in point of fact, I suppose that that may have been the case of others, which has been mine; and I know, that, with advantages of education as good as the average, I had reached the age when the militia-man is discharged from his principal service, without having any fit sense or perception of the worth or the grounds of the institution. Our fathers understood this thing better. There was a high philosophy in their right feelings and strong sense. They did not call on men to do what they forbore to show them the reasons, and excite in them the feeling, for doing. Among other arrangements to the end, they sanctified these occasions of concourse with ‘the word of God and prayer;’ a practice, of which this company’s annual solemnities present an interesting relic. If some things, which were done in our father’s days by prayers and sermons, are to be done in ours by other forms of speech, then let us have the benefit of the altered fashion. Let some additional attraction be given to the days of militia parades, and some additional advantage be derived from them, by devoting part of the day to some such useful expositions of the worth of the institution, as there is not a village of our Commonwealth not affording more than one person competent to present. They need not be what some of us lately heard over the bones of the militia proto-martyrs of Lexington, to send every hearer away with a glowing sense of the duty of defending such a country , and the privilege of having such a country to defend.—But these hints must have an end. Let me give them one by saying, that, if the militia service is not rendered with satisfaction and alacrity, having such purposes and such associations to recommend it, there are others who must share the blame with those who feel the reluctance and the discontent.

Gentlemen of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, I shall address you very briefly in conclusion, for the proper time has not only come, but gone, for me to relieve your patience, and that of your guests. Your institution appears to have been designed, by noble hearts, for noble ends. It might be called in the use of hardly too strong a figure, the corner stone of the militia organization of Massachusetts, as it has also been a distinguished ornament of that body in later times. With such a history to animate you, with such a reputation to support, you are reasonably looked to, to be, in time to come, useful and true friends to all good institutions of the good Commonwealth; and to be willing, as those who went before you were, to go to the death in defense of her liberty and laws. Vigilance, gentlemen, vigilance erect and in panoply, is what providence has made the price of a people’s safety. See you, with other good citizens, that it does not sleep, and see further that it watches in armor. Hitherto the objects, at which your venerable founders aimed, have been essentially secured. You approach the close of the second century of your company’s age, under auspices of the country, such as to rejoice a patriot’s heart, yet not altogether unmingled with causes of solitude. The one should make him thankful to God, and to good, and wise, and valiant men, God’s instruments; the other should not make him fearful, but they should make him watchful. I say more, repeating what I have said. If present causes for watchfulness did not exist, his want of watchfulness would be still most imprudent, for that very want would create them. Do your part, gentlemen, and let the rest of us in our lot, do ours, and let the same spirit live in those who are to take our places, as it did live in those places we have taken, and, by that blessing of Almighty God, which waits on upright human endeavor, the coming ages, as one after another they roll in their flood of the mysterious experience of human fortunes, will still find our beloved Commonwealth the happy seat of liberty and law; and through them, and through causes which they protect and foster, the seat of universal competence, a ripe learning, a patriotic brotherly love, and, a pure, fervent, and operative piety. And so it will be a marked spectacle, for all eyes of the world, as a field which the Lord hath blessed.

OFFICERS

OF THE

ANCIENT AND HONORABLE ARTILLERY COMPANY

FOR THE YEAR 1834

Lt. Col. Grenville T. Winthrop, Capt.

Col. Thomas Livermore, 1st Lieut.

Lt. Col. Abijah Ellis, 2nd Lieut.

Lt. Col. Francis R. Bigelow, Adjutant.

FOR THE YEAR 1835

Brig. Gen. Thomas Davis, Capt.

Col. Josiah L.C. Amee, 1st Lieut.

Capt. Samuel Knower, 2nd Lieut.

Capt. Charles A. Macomber. Adjutant

June 14th is the birthday of the Army, created by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775.1 The next day, George Washington was elected Commander-in-Chief2 and soon issued orders that set the tone for the military, including one declaring:

June 14th is the birthday of the Army, created by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775.1 The next day, George Washington was elected Commander-in-Chief2 and soon issued orders that set the tone for the military, including one declaring:We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood (like France)–if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage–if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth–if the Star-Spangled Banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization–we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.4

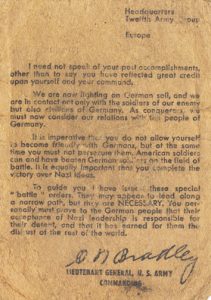

And in WWII, General George Marshall spoke about the mission of the United States:

And in WWII, General George Marshall spoke about the mission of the United States:

President John Adams oversaw the construction of the Navy,

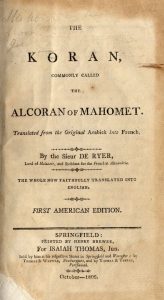

President John Adams oversaw the construction of the Navy, In short, if you read the Koran, you will understand their unprovoked attacks against us. But the fighting still wasn’t over. While America was engaged in the War of 1812 against Great Britain, Algiers (one of the Muslim Powers that had negotiated a peace treaty with the US in 1795

In short, if you read the Koran, you will understand their unprovoked attacks against us. But the fighting still wasn’t over. While America was engaged in the War of 1812 against Great Britain, Algiers (one of the Muslim Powers that had negotiated a peace treaty with the US in 1795

On March 3rd, 1931, an

On March 3rd, 1931, an  At that time, attorney Francis Scott Key

At that time, attorney Francis Scott Key

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city Hancock and Adams were staying in the home of Lexington Pastor Jonas Clark.

Hancock and Adams were staying in the home of Lexington Pastor Jonas Clark.

On April 6, 1917, the US entered World War I,

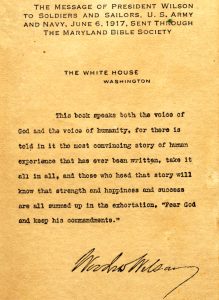

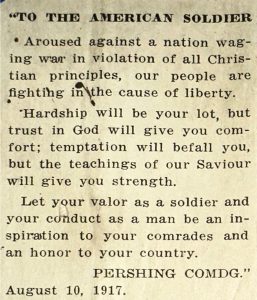

On April 6, 1917, the US entered World War I, Also, throughout American history, Bibles have been distributed to soldiers going into war and sometimes these Bibles would include messages from leaders on the importance of Bible reading. For example, a letter from President Woodrow Wilson was used in a WWI era Bible (pictured here from a Bible in WallBuilders’ Collection):

Also, throughout American history, Bibles have been distributed to soldiers going into war and sometimes these Bibles would include messages from leaders on the importance of Bible reading. For example, a letter from President Woodrow Wilson was used in a WWI era Bible (pictured here from a Bible in WallBuilders’ Collection): To The American Soldier:

To The American Soldier:

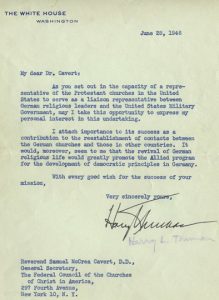

President Harry Truman

President Harry Truman  4. To avoid acts of violence, except when required by military necessity.

4. To avoid acts of violence, except when required by military necessity. As you set out in the capacity of a representative of the Protestant churches in the United States to serve as a liaison representative between German religious leaders and the United States Military Government, may I take this opportunity to express my personal interest in this undertaking.

As you set out in the capacity of a representative of the Protestant churches in the United States to serve as a liaison representative between German religious leaders and the United States Military Government, may I take this opportunity to express my personal interest in this undertaking.

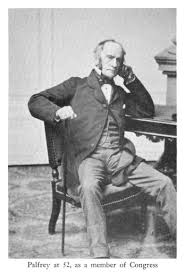

Palfrey’s grandfather, William Palfrey, had been active during the American War for Independence, working for John Hancock, being aide-de-camp for George Washington, and then serving as the Continental Congress’ diplomat to France. The grandson was born during George Washington’s presidency and graduated from Harvard in 1815, during James Madison’s presidency. He studied theology, and three years later in 1818 became pastor of Boston’s Brattle Street Church. In 1831, he left the church to be Professor of Sacred Literature at Harvard, eventually becoming dean of the theological faculty and one of three preachers at the university chapel. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, he became involved in government, serving in the US House of Representatives from 1842-1843 and 1847-1849, and as Secretary of State in the years between. He served as Boston’s postmaster from 1861-1867, then went to Europe in 1867, serving as US representative to Anti-Slavery Congress in Paris. He penned numerous works, including the History of New England to 1875, The Relationship between Judaism and Christianity, Academical Lectures on the Jewish Scriptures and Antiquities, and Discourse . . . [on] the Second Centennial Anniversary of the Settlement of Cape Cod. He also served as editor of the Commonwealth newspaper and the North American Review.

Palfrey’s grandfather, William Palfrey, had been active during the American War for Independence, working for John Hancock, being aide-de-camp for George Washington, and then serving as the Continental Congress’ diplomat to France. The grandson was born during George Washington’s presidency and graduated from Harvard in 1815, during James Madison’s presidency. He studied theology, and three years later in 1818 became pastor of Boston’s Brattle Street Church. In 1831, he left the church to be Professor of Sacred Literature at Harvard, eventually becoming dean of the theological faculty and one of three preachers at the university chapel. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, he became involved in government, serving in the US House of Representatives from 1842-1843 and 1847-1849, and as Secretary of State in the years between. He served as Boston’s postmaster from 1861-1867, then went to Europe in 1867, serving as US representative to Anti-Slavery Congress in Paris. He penned numerous works, including the History of New England to 1875, The Relationship between Judaism and Christianity, Academical Lectures on the Jewish Scriptures and Antiquities, and Discourse . . . [on] the Second Centennial Anniversary of the Settlement of Cape Cod. He also served as editor of the Commonwealth newspaper and the North American Review.

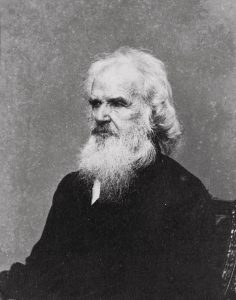

Born in Connecticut to a well-known family, he graduated from Yale in 1804. He worked as an educator for several years, then began studying law. In 1812, he passed the bar and went to work as a lawyer in Newbury, Massachusetts. But being dissatisfied as an attorney he became a merchant in Boston, then Baltimore, and next entered the study of theology. He graduated from Cambridge Divinity School and was ordained in 1819. He pastored a Boston church until 1845, then a church in Troy, New York, until 1849, and then another church in Massachusetts, where he pastored until 1856. While a pastor, Pierpont penned two of the more popular classroom school readers of that day. He was an abolitionist, a member of the temperance movement, a Liberty Party candidate for governor in the 1840s, and then a Free-Soil Party candidate for governor in 1850. He served as a Massachusetts field chaplain during the Civil War, but the physical demand was too great for his aging body, so he took an appointment in the Treasury Department in Washington, where he worked until his death in 1866. He was an accomplished poet and penned many published poems as well as sermons.

Born in Connecticut to a well-known family, he graduated from Yale in 1804. He worked as an educator for several years, then began studying law. In 1812, he passed the bar and went to work as a lawyer in Newbury, Massachusetts. But being dissatisfied as an attorney he became a merchant in Boston, then Baltimore, and next entered the study of theology. He graduated from Cambridge Divinity School and was ordained in 1819. He pastored a Boston church until 1845, then a church in Troy, New York, until 1849, and then another church in Massachusetts, where he pastored until 1856. While a pastor, Pierpont penned two of the more popular classroom school readers of that day. He was an abolitionist, a member of the temperance movement, a Liberty Party candidate for governor in the 1840s, and then a Free-Soil Party candidate for governor in 1850. He served as a Massachusetts field chaplain during the Civil War, but the physical demand was too great for his aging body, so he took an appointment in the Treasury Department in Washington, where he worked until his death in 1866. He was an accomplished poet and penned many published poems as well as sermons.