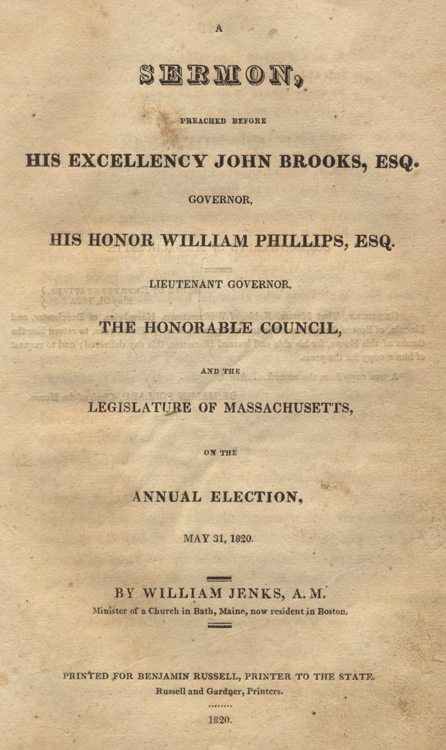

Henry Ware (1764-1845) graduated from Harvard in 1785. He was pastor of the First Church at Hingham, MA (1787-1805) and was Professor of Divinity at Harvard (1805-1840). The following election sermon was preached by Ware in Massachusetts on May 30, 1821.

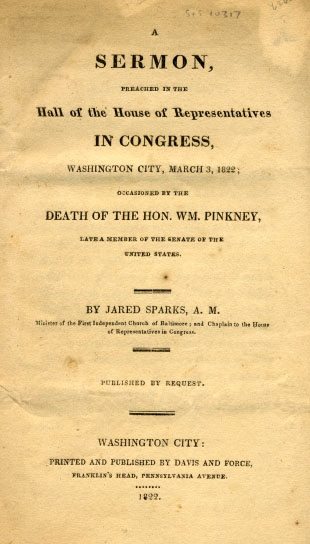

A

SERMON,

DELIVERED BEFORE

HIS EXCELLENCY JOHN BROOKS, ESQ.

GOVERNOR,

HIS HONOR WILLIAM PHILLIPS, ESQ.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR,

THE HONORABLE COUNCIL,

AND THE TWO HOUSES COMPOSING THE

LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS,

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

MAY 30, 1821.

By Henry Ware, D. D.

Hollis Professor of Divinity, in Harvard University.

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS.IN SENATE, MAY 31, 1821.

Ordered, That the Hon. Messrs. Williams, Tilden, and King, be a Committee to wait upon the Rev. Henry Ware, and in the name of the Senate, to thank him for the Sermon by him delivered before His Excellency the Governor, the Lieutenant Governor, the Hon. Council, and the two Branches of the Legislature, and to request a copy thereof for the press.

Attest,

S. F. McCLEARY, Clerk.

SERMON.ACTS………CHAPTER XVII. VERSE 26.

“And hath made of one blood all nations of men, for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

IN no point does our religion present itself to us with a deeper interest, in nothing does it recommend itself more strongly to cultivated minds, than in the representations it gives of the character of God, his relation to his creatures, and his dispositions towards them. That he is the creator of all things, and that all beings are the work of his hands, is not the only, nor is it the principal consideration that it offers to us. Images of a more tender kinds are frequently presented, and he is declared to sustain a relation, which implies more of interest, and expresses more of nearness and affection. The author of our being stands in the relation of a father to us; and we are declared to be his children, for whom he feels a parental kindness; over whom he holds a father’s authority. The same God, also, is to be acknowledged as the father of men of all nations. Nor only so; he has made them, as my text asserts, all of one blood, to possess a common nature as well, as to have a common origin; and thus to sustain not only the same relation of children to a common parent, but also that of brethren to each other.

The double relation in which our religion represents us as sustaining toward the author of our being, and toward one another, is closely connected with many of the most important duties as well, as the highest interests of the social state. It regulates the dispositions and the conduct, which individuals owe to each other. It relates also to those, which are due from collective bodies of men, from communities and states one toward another. It prescribes the principles, upon which the members of a government are bound to act, in the conflicting interests of the community or state, which they represent, and for which they act, and other communities, or individuals of the same, or of another community.

Indeed there is nothing in the intercourse of men with each other, in any of the political, or civil, or social relations, which will not be affected by a just view of this universal relation, which binds together and embraces in one, the whole human family.

I have thought the subject not an unsuitable one to b addressed, on the present occasion, to an assembly of Christian rulers; as it suggests a principle, which should serve as a guide to them, in all their endeavors to promote the public good.

While our religion teaches expressly the doctrine of the text, the spirit which it everywhere inculcates, and the whole system of its precepts are of a character correspondent to those relations, the nature and the obligations of which it discovers to us. On the one hand, it is everywhere implied, that all men of every nation owe the same obedience to the common father of our race, are alike objects of his care, subjects of his moral government, accountable to him, equally capable of obtaining his approbation, and securing his favor by holiness, or of forfeiting it by sin, and a life of impenitence. This view, while it leads us to a just sense of the duty we owe to the author of our being, is calculated also to give us enlarged and liberal notions respecting our fellow-men, and to prepare us to honor, esteem, and love them.

On the other hand, everywhere in the same manner is implied the obligation of universal good will to one another, grounded on the same considerations; the common origin of our race, our common allegiance to the universal parent, and the relation we sustain to each other as brethren.

We see then the design and the tendency of our religion in a point of view, in which it displays its most amiable and attractive features, and exerts its noblest powers. Not exclusive but comprehensive is its spirit. Not to separate but to combine, not to drive men asunder, but to unite them together, and bind them by new ties of interest and affection is its tendency. Breathing kindness and good will all around, it produces, not hatred and hostility, not mutual injuries and deeds of violence, but love, and harmony, and peace. Not within a narrow circle is its attractive power confined—repelling all that is beyond. There are no limits, beyond which its attractions are unfelt. It reaches beyond the bounds, which limit all the other principles of union, which operate upon the human mind, and draw men together. Beyond those of interest and personal affection. Beyond those of family, of nation, of country. It embraces every country, every nation, every region, and all the families and tribes of men. And throughout the whole range of its local influence, how various are the effects it produces! Its design is no less, than that of putting down all that is narrow, and selfish, and exclusive and hostile, in the intercourse of men, in the institutions of society, in the customs that prevail, in the feelings that are cherished. It is to break down all those walls of partition, which pride, and selfishness, and passion, and jealousy, and prejudice, and fear, have erected, between nations, and between the several tribes and families of men. It is to sweep away the barriers which local prejudice or interest have raised up, between those who inhabit different regions of the earth, or different portions of the same country. It is to annihilate the odious distinctions, which are grounded on difference of colour, and feature, and form, and manners, and laws, and government, and religion, and usages; distinctions, which have laid the foundation and furnished the pretext, of so much of the violence, and oppression, and slavery, and war, that has disfigured and disgraced the world in all ages, and rendered it too often a scene of hostility and blood, and desolation. It is, not indeed to do away entirely, but to reduce and soften, and to check all that is unkind and revolting in those distinctions, of which the providence of God, or human institutions have laid the foundation, in the conditions of men of the same community; between the rich man and the poor, the learned and the ignorant, the master and the servant, the parent and the child, the public officer, and the private citizen. For, in those institutions, through the instrumentality of which it produces all its great and salutary effects, it presents one spot, where all human distinctions are leveled. There, in the temple of the Most High; in the presence of Him, who alone is great, all human greatness disappears, and the rich and the poor, the prince and the peasant, the bond and the free, meet together upon equal terms.

These are the offices, in which our religion exerts its power, and displays its excellence. Thus does it cause men of different nations and of distant regions, to lay aside their spirit of hostility, to treat each other with justice, and kindness, and good faith; to live in peace, and in the interchange, as they have opportunity, of offices of good will. Thus does it bind together citizens of the same state, and members of the same community, by ties, that no competition of interest, or conflict of opinion, or difference of education, or variety of manners, have power to dissolve. Thus does it prostrate all those factitious, unnatural, artificial distinctions, which pride, and selfishness, and prejudice, and the love of power, have introduced; leaving only those, which the God of nature has established, and which are essential to the order, and peace, and well being of the moral and social system.

And all these effects it produces, without disturbing the regular course of human affairs, as established by the institutions of society; without interfering with any legitimate rights; without diminishing the authority of human government, or preventing the full exercise and influence of those private affections, and personal attachments, which belong to the domestic relations; or those which bind a man to his country, to the land that gave him birth, and to the society, with which are connected all his interests and attachments, and all the duties of a social being.

But Christianity has sometimes been reproached with teaching the obligation of universal benevolence and good will in a manner, which leaves no room for the private affections, no room for particular friendship, for any of the peculiar duties of the near relations, or those, which a man owes to his country. And it has been objected to it that, in the same spirit, it requires meekness, forbearance, and abstinence from resistance in a manner, that is incompatible with the rights of self-defense, and the authority of human government. But it is important to show, and it may be shown in the most satisfactory manner, that our religion is not liable to this charge; and that it is a mistaken view, and a false representation of its character, which subjects it to such an imputation. It is important for us to understand how far from the truth is the charge, that our religion is unfriendly to the full exercise and expression of the private and particular affections; those affections which are due from a man to his country, his kindred, his family, his friends; that it either renders him insensible to those relations, or that it requires of him anything, that is incompatible with either of them. Certain it is, that the enlarged and comprehensive spirit of the gospel has nothing in it adverse to private affection, and personal attachment. Its office is to control, to limit, and to give a right direction to the private and particular affections, not to destroy them, nor to set them aside.

By enlarging the circle through which its influence extends, it does not diminish the warmth with which it glows nearer the centre. While it carries abroad your affections, as far as there are objects, on which they can fall, and your good wishes and good offices as far, as there are beings to be benefitted by them, it permits and encourages a peculiar and warmer affection, a nearer interest, and a more active care toward your family, your friends, your neighbors, the members of the society to which you belong, your country; and you are bound to seek their good in a manner, and to a degree, in which you are not bound toward any, who are beyond those relations. But you are not to forget, that these affections and these obligations, though peculiar and specific, are not exclusive. They are not to diminish your affections, nor to relieve you from your duty to strangers; and those who are distant. They are not to be indulged and followed, where they would interfere with the obligations of general humanity, and the offices of kindness and good will, which are due to all.

But we are invited by this occasion to contemplate the spirit of Christianity chiefly in relation to its influence upon the conduct of men, who in public stations are acting for the public; and particularly upon the legislative and executive government of the state. Now, whether we consider those duties of a government, which arise from the relations of the state or nation to other states, or its relation to its own citizens, Christianity will require of each man, who has a share in administering the government, to act upon a higher and broader principle, than those common maxims of worldly policy, which are usually considered a sufficient to indicate to him the course he should pursue. According to these maxims and rules, the highest motive by which he is to be guided is what is called patriotism, or the love of country; and it is enough, if he faithfully devote himself to the interests of his country, if he pursue its prosperity, and seek its good with a steady zeal, and a single aim. If he suffer no personal interest to come in competition with it, so as to make him prefer the private to the public good, he is thought to act with sufficiently enlarged views, and from motives sufficiently elevated and disinterested. But our religion demands of him something more. While it approves and cherishes the love of country, and itself prompts to every proper deed by which the love of country can be expressed, it requires that it be controlled and limited by a higher and more enlarged principle, that of general benevolence; a principle which will not allow him to advance the interests of his own country upon the ruins of another; which will not permit him, from any prospect of advantage to his own country, to invade the rights of another, or to commit any act of injustice or oppression, or cruelty. Patriotism in its true and proper import is entirely coincident with the spirit of Christianity. In this large and liberal sense, it is inculcated by all those precepts of the Saviour and his Apostles, which tend to the peace and order of society, which require subjection to lawful authority, and promote rational liberty. It was exemplified by the Saviour himself in an affecting manner, when he wept over the approaching calamities of his country, and expostulated with her for that irreclaimable wickedness, which was bringing down upon her the vengeance of Heaven. And it appears with lively interest in the example of the Apostle Paul, expressing a readiness to suffer himself for his brethren, could he but thus save them from the punishment they had incurred, and which was about to fall upon them.

But that patriotism, which stops short of this, have little claim to our respect; it has no title to so honorable a name. Indeed, whatever name it may assume that is in fact but selfishness, a little disguised, and a little refined, which limits its affections, its exertions, its duties, and its cares, wholly to its own country and regards all beyond without sympathy, and as having no claims upon our benevolence or justice. For what is the character, and what the source and motive of that patriotism, which is thus limited and stinted, and makes not a part of universal benevolence, but is exclusive of it and stands opposed to it? The patriot of this school loves his country; but it is only because that country embraces all his own interests, comprehends all his friends; its prosperity is his own prosperity, that of his family, that of his children. In providing for it, and seeking to promote it, he is making the best and only sure provision for himself and his family. His own well-being and prosperity, his own honor and aggrandizement are identified with those of the state, and must rise or fall with it. All this is very well, but it has little praise. Christian patriotism is prompted by a higher motive, and is governed by other rules. It remembers the words of the Saviour, when he asks, “If ye love them that love you, if ye do good to them that do good to you, if ye salute them that salute you, what thanks have ye?”—The obligations of love, of good offices, and of courtesy, he confines not to his friends. He acknowledges the obligation of good will and good deeds, where there can be no return, and where there is no personal interest. He feels himself bound, to do justice to all, to wish well to all; and as he has opportunity to do good, not to his brethren, his kindred, his countrymen only, but to all.

How frequently will it happen, that in a competition of interests and conflict of rights between his own country and a neighboring state, the demands of justice and the calls of patriotism shall seem at variance. Justice to another state, requires him to forego important advantages, and will not allow him to avail himself in behalf of his own country, of opportunities for securing to her advantages, which would give her an ascendency over her neighbors. In such cases, what is the course, which patriotism, as it has been usually understood, and the common and approved maxims of worldly policy, will dictate? Will he, who has no higher principle to govern his conduct, hesitate to seek the aggrandizement of his own nation at the expense of neighboring or distant states? Will he feel himself bound to forego the opportunity of raising his own country to power, or wealth, or greatness, when he knows it can only be effected by taking undue advantages of the situation or the necessities of another; by measures, which tend in equal degree to their impoverishment, depression, and ruin? Will he refuse, will he not even feel himself required by the principles of patriotism which he professes, to give a check, if it be in his power to that prosperity of a neighboring state, which stands in the way of that of his own? There is no doubt, I presume, what answer the history of nations and of governments will report to these questions.

But Christian morality is of a more pure and elevated and disinterested character; and Christian patriotism founded on it, revolts at the thought of deriving a benefit from another’s wrong; of building his country’s glory, and greatness, and posterity, on the ruins of another people. It enkindles an ardent zeal for his country’s good. It impels him to all honorable and virtuous means for its promotion; to faithful exertions, to heroic personal sacrifices. It makes him ready to do and to suffer for the public safety and welfare. But it authorizes no act that is inconsistent with the rights, or that must impair the prosperity of another country, or another individual. The Christian patriot will no sooner pursue measures to erect his country’s glory, on the ruins of another people; to advance her power and prosperity by conquest, oppression, or slavery; or by any methods of checking the prosperity of a rival state, bringing a great evil upon it for the sake of some benefit to itself, or drawing off to itself the sources of its wealth, and the means of its safety, than he would raise his own private fortunes on the ruins of his country, or the injury of his neighbors.

Occasions may occur again, and they are likely to be frequent, in which the local interest of that section of the state, in which you live, and which you immediately represent, may stand in competition with the general interest of the state, or of some other part of it; and would be advanced by measures, that must prove hurtful to the whole, or to some other part. In such cases, a legislator, whose views of duty are narrow and contracted; who considers himself as acting for a part, and not for the whole; who is guided by no higher principle than a selfish policy, will prefer the private to the public good, will seek the particular at the expense of the general interest; will favor the views and wishes of one part of the community, where he knows he must y the same act, bring injury, distress, and loss, perhaps ruin, upon another, with which he is personally less connected, and to whose interests he feels himself less strongly bound.

How different, in each of these cases, will be the conduct of him, who carries with him into his public conduct, the enlarged views and liberal feelings of the gospel!—Who, in being a legislator, a statesman, or a magistrate, does not forget, that he is yet a Christian! Does not forget, that as all men are brethren, of one blood, of one parentage, of one nature, all are entitled alike and equally to the same measure of justice, and kindness, and humanity. He will revolt at the thought of the aggrandizement of his own country by a violation of that justice and humanity, which are due to another people; of advancing the interest of that portion of the country which he inhabits, by that which impoverishes, or lessens the prosperity of another part; or of attaining to personal ease, or affluence, or honor, by a course of measures, which bring undeserved disgrace, or poverty, or misfortune upon any other individual, however remote and unconnected.

Such, my respected hearers, is the general duty of all, and especially of those, who, in the important offices of government, are to watch over the public interests, and to give a direction to the public transactions; a duty resulting from the consideration, that God has made all men of one blood, that all constitute one great community. There are some particular things, which by the consideration of this tie, by which all are bound together, and of the duties implied in it, the rulers of a Christian community will keep in view in all their exertions for the public good. In the first place, in all measures, which have any influence on the elations of the whole, or the mutual relations of the several parts of the state, they will pursue a pacific policy. No measure will receive countenance and support, which has an evident tendency to interrupt, either with surrounding states, or between the several portions of the state, or of its citizens, the relations of peace, and the interchange of friendly offices. Care will be taken, that none be adopted; that are calculated to nourish a spirit of hostility, to awaken mutual jealousies or party prejudices, or to excite any of those passions, which alienate the members of the same community from each other, or by which their pursuits or their interests become irreconcilable. I need not say how adverse the spirit of war is to the spirit of the gospel; nor how well it becomes a Christian government, by a just and humane, and liberal policy, both in respect to its external and internal relations, to keep peace with all, and to endeavor to hasten the universal establishment of the kingdom of the Prince of Peace, and the universal reign of that righteousness and peace, which it was to introduce into our world.

Another circumstance, of which a Christian government will never lose sight, is, its duty to protect the personal liberty and maintain the equal rights of all. It is not required, in order to this, to bring all men to the same level by destroying those distinctions, which the constitution of nature has established, or the institutions of society have sanctioned. Equality of rights may remain amidst all the varieties of condition, and talents, and acquisitions, and character. It stands opposed to exclusive privileges, by which one section of the country, or one class of its citizens is enriched or aggrandized at the expense of another, or has advantages granted to it, which are denied to others under similar circumstances. It stands opposed to any favor or preference shown in the framing of laws, or in their execution to one political sect over another, or to one denomination of Christians over another. It is opposed to the subjection of any portion of the inhabitants of a country to a state of involuntary servitude, to the loss of personal liberty, or of any of their civil or political rights, which have not been forfeited by crimes, that render their continuing to possess them inconsistent with the public safety. It is opposed, in fine, to everything in the structure, and in the administration of the of the government of the state, which implies partiality, which grants to some, what it denies to others, under similar circumstances. It will be the care of a wise and righteous government to carry a steady hand, and maintain an impartial course, amidst the constant and ardent struggles for superiority and particular favor, which employ so much of the activity and zeal of the several religious and political sects, into which every community is divided, and the competition of each class of citizens to gain some advantages over other classes, and of each individual over other individuals of the same class.

Another, and it is the only other leading object I shall mention, will be to make provision for extending the means of good education to every section of the country, and to every class of the inhabitants. By the constitution of our nature we all come into being upon equal terms; equally helpless, equally dependent, and equally objects of the complacency and the care of our common parent. But, no sooner are we born into the world, than more circumstances, than can be named or imagined, contribute to destroy this original equality, and to produce that infinite variety, which we find, in the condition, and in the characters of men. The different discipline to which we were from the first subjected; the different fidelity or neglect of our parents in our early instruction; the different influences, to which we were exposed by the examples usually before our eyes in our early years; casual associations, to which in early and in mature years we were introduced; difference of industry, of activity, of enterprise, when we came to engage in the business of life; difference of occupation, to which choice, or accident, or necessity, or parental authority may have destined us; by all these, and numberless other circumstances, this equality of nature soon disappears, and human society is made up of an infinite variety of all extremes. Now it should be the great object of a Christian government, keeping steadily in view the common origin of all, “formed of one blood,” to restore, as far as can be done by proper means, that original equality from which men have departed so far. And this is to be effected, not by an arbitrary equalization of property, and leveling of all distinctions of rank and power, which industry and education, and talents, cannot fail to give; and which they must soon restore again, were they taken away by violence; but by correcting as far, as it is in their power, the source from which the difference between one man and another in all these respects, has in a great measure sprung. It is by providing that the means of education shall be extended to all. That education I mean, which is not confined to the rudiments of knowledge, but which relates also to all the principles and habits of an intellectual, a moral, and immortal being; a member of the social body, and a subject of the moral government of God. It is by multiplying the means and perfecting the system of intellectual, moral, and religious education in general, and by allowing no portion of the country, and no class or description of its inhabitants to be left by the necessity of their condition without them. It is by urging home to the very bosoms of men, the inducements to use the means and opportunities that are offered them, for themselves, and for their children. It is to press upon men the motives to habits of industry, frugality, sobriety and temperance. It is to encourage, by legal provisions and by their example, institutions and associations, which piety, humanity and patriotism have suggested, for promoting these most benevolent purposes.

It is the distinguishing glory of the age in which we live, to abound beyond all former example in the exertions of voluntary associations for preventing indigence and for mitigating its evils; for suppressing vice, and for encouraging and promoting industry, frugality, economy, and habits of temperance and virtue, and for sending that religious knowledge, which may form the whole character, and influence the whole condition of life, home to the families and firesides of those, who might never have been induced to put themselves in the way of receiving it. It is the spirit of that religion, which teaches, that we have all one father, and that we are all brethren, that is producing these effects; that is thus seeking to bring men nearer together, not by impoverishing the wealthy, but by enriching the poor; not by bringing down the lofty, but by raising the low; not by leveling the distinctions of learning, and wisdom and virtue, but by enlightening the ignorant, and raising men from the degradation of folly and the corruptions of vice to the elevation of the wise and the virtuous.

I observe, that it is the spirit of our religion, that is producing all these effects. But how late have Christians been in learning this application of its principles, and this method of accomplishing its design! How partial and limited still in the Christian world is the application of the great principles and spirit of the gospel to public transactions, and the conduct of governments. Not only has it been overlooked in the intercourse of nations with each other, so that they have regarded each other as natural enemies, rather than as brethren of one great family; but it has been unacknowledged and unthought of in the relation that subsists between the government and the citizens of the same state. How long were Christians in coming, from the fact, that “all were made of one blood,” to the just conclusion respecting the natural freedom and equality with which men are born into the world! It is a lesson, indeed, which most Christian nations have still to learn. Principles are acknowledged and practices pursued, that are utterly irreconcilable with that natural equality as to rights, which is the basis of all relation of all to a common parent, which Christianity teaches. Instead of this, it is practically admitted, that some are born to rule, and others to be subjects, some to possess power and rights, and others to have only the privilege, to obey and to suffer. And so long have the nations of the earth submitted to this unnatural state, so long have the many been subjected to the control and disposal of the few, that they have lost the power of self government and self direction. The chains they have worn so long, that they have grown into the flesh, and are not safely to be removed. Men have so long been without power, that there is reason to apprehend they would make a fatal use of it, were it suddenly put into their hands. So long have they been without liberty, and without rights, that they require time and discipline to teach them their value and their use, before it would be safe to entrust them in their hands. The evidence of this state of things, we have in the current events of the day, and in the history of the last thirty years. Men have been accustomed in most countries to pay their homage to hereditary power, and to be dazzled and awed by its external insignia, till they are unable to perceive the immeasurable distance between that which is intrinsic, and that which is adventitious in human greatness; to perceive how far the chief magistrate of a nation or state, elevated to the chair of government by his talents and his virtues, and placed in it by the free suffrages of an enlightened people, rises above him who is seated, by the mere chance of his birth, upon a throne, whatever the splendor and power with which it is surrounded.

Our religion teaches us, that God has made all men of one blood, and that we are all brethren; but by the institutions of society in some countries, and by common usages and the prevailing practice in almost all, one might well be led to suppose, that men believed themselves to be wholly unrelated to each other; that the several nations of the earth, and the several classes of the inhabitants of each country had no common origin, and no common interest. Confirmation of this opinion we should find in the general hostility manifested by the several nations toward each other. It has been such, that in all countries and in all ages, it has been reckoned one of the highest virtues of a citizen, to love his own country, and to seek her good, exclusively of all others, in a manner irreconcilable with the obligations of general benevolence, and with the notion of a common nature, common origin, and the relation of brethren belonging to all. Patriotism accordingly in the political vocabulary is defined to be a narrow, exclusive passion, which permits, if it does not even require us, to hate all the rest of mankind, whenever the supposed glory, or interest of our country comes in competition with that of any portion of mankind, who are out of those limits. We should find it also in the selfishness, and cruelties, and oppressions that are permitted in all countries; in the degradation and abject servitude to which, in many countries, a large portion of the population is born, as their natural inheritance, and inevitable lot, from the odious distinction of casts so disgraceful to pagans in the eastern hemisphere, to the still more horrible system of African and American slavery, by which so indelible a stain is fixed upon Christians in the western.

That Christians in other countries, besides our own, are beginning to understand, better than they have done, the spirit and the demands of their religion, and to apply it to correct the abuses of government, its false principles and maxims, and the evils of the social state, is a just cause of joy, and a reasonable ground of hope. That a cause against which so many passions, and prejudices, and interests are armed, should meet with opposition, and occasionally fail of success, is what we are to expect. But of its eventual prevalence, and final triumph, we have a sure pledge in the effects already achieved, and in the engines which are brought into activity to accomplish the rest; but above all in the assurance that it is the cause of humanity, the cause of truth, the cause of God—and that God will own and vindicate his cause.

There are several circumstances, which give peculiar interest to the present occasion, and furnish unusual reasons for public joy and gratulation [thanks]. I shall confine myself to the mention of two.

The first is the public sense, so clearly expressed in the recent election, of satisfaction in the past administration of the government of the state. As the highest reward that those, who serve the public, can receive, is to know, that their services have been acceptable; that their well meant endeavors to promote the public good have been successful, and have met the approbation of their fellow citizens: so is there no method, by which the public sentiment respecting the administration of government can be so distinctly expressed, as by the reappointment of the same persons to the important offices of the state.

In the reelection of those distinguished citizens to the two first offices in the government, whose faithful services, in high stations and important trusts, the public has enjoyed for so many years; and in the return of so large a proportion of the Senators and Representatives of the last year to compose the Legislature of the present; an honorable testimony is given of the public satisfaction in the wisdom, fidelity and usefulness of their past services, and of the general confidence which they have inspired. We contemplate the fact also in a still higher view; as an assurance to us of the strength and stability of our institutions, and of the good sense and good spirit of the community; and that there is intelligence enough in the people to enable them to understand when they are faithfully served by those, in whose hands they entrust the public interests; and correct principles enough to approve and to encourage public virtue, public spirit, and upright and well directed services.

While we notice, and mention on this occasion with great satisfaction, these tokens of a wise and faithful administration of the civil government, of the public prosperity and tranquility, which are its natural consequence, and the general expression of approbation it has received; we regard it, also, as a promise of the future. It invites us to confident hope, and the indulgence of pleasant anticipations of the future management of the interests of the state. It enables us to feel assured, that the administration of the government, will be committed hereafter, as it has been hitherto, to able and faithful hands; and that the people, after exercising with sound judgment and due care their right, in the selection of those, to whom their most important interests are to be entrusted, will be reasonable and just in the judgment they pass afterwards upon the manner in which the trust has been executed; and ready to express their approbation and gratitude, wherever they shall have been merited by a steady pursuit of the public good.

The other circumstance, to which I alluded, as imparting a peculiar interest to this, beyond what we have felt upon similar occasions, is the evidence we have had the opportunity of witnessing in the course of the past year, of the general satisfaction of our citizens in the principles and form of the government itself. The people have been called upon to express their opinion, not only as they have annually opportunity to do, of the administration, but also of the constitution of our government. The result is the most gratifying, the most encouraging, and the most honorable, that could have been anticipated. It has exhibited a new proof of the soundness of those principles upon which our government is founded. It has taught us what before was doubtful, and must have remained so until the doubt was removed by such an example, the practicability of perpetuating republican principles and republican institutions. We have now to offer, in proof of the stability of republican institutions, the example of a people, to whom, after an experiment of forty years, the form of their government has again been submitted for revision, to be wholly set aside, or altered, or preserved entire, according as experience shall have taught them to regard it as sound in its principles and forms, or defective, or radically wrong. That it has passed through the trial, to which it was subjected, without any injury, with so few alterations, and with all its important original features unchanged; while it is so honorable to the prospective wisdom of the illustrious men, its original framers, reflects not less honor upon the wisdom of the equally great men, who were appointed to revise the instrument; and upon the good sense and moderation of the people in the primary assemblies, to whose final decision the amendments which it was thought proper to make in it, were submitted. We have learned, what it is most consoling and encouraging to know, that there is not in them that restlessness and love of change, which would make them willing, in pursuit of an unattainable object, to put at hazard all that is valuable in their civil institutions.

There is probably no other country on earth, where the same experiment could have been made with safety; and it may be doubted whether, in every part of this, it could have been done with equal probability of a favorable issue. If it be asked, to what it is to be attributed, that we have been able, without violence, without force, without civil commotion to accomplish that, which in other countries, the friends of rational liberty and good government dare not attempt; the answer is easy and satisfactory. It is to be found in the principles and habits of the people; in the religious and moral character of the inhabitants of this state; in the state of society, derived originally from our ancestors; brought with them when they came to this country; preserved and improved by the institutions which they established, and the provisions which they made, and which are yet continued, for religious instruction, for general education, and for the general diffusion of knowledge and virtue.

It is to your reverence for religion and its institutions, the general respect paid to the Christian Sabbath, and the worship of God in public assemblies, to the general diffusion of knowledge among all classes of people, and the system of education, by which provision is made for extending competent means of instruction to every family and every child. It is to these, that you owe that elevation of moral and intellectual character in the great body of the people, those sober habits, and those just views, by which they are qualified for the enjoyment and the preservation of a free government; capable not only of selecting from among themselves, the men who are best qualified for the several offices in the administration of their government, but also of determining the great principles and rules upon which its administration shall proceed, of choosing the kind of government under which they will live.

The considerations which discover to us the causes, to which we are to attribute those circumstances in our condition, by which we are so happily distinguished, and for which we have so much cause to be grateful; point out to us also, and urge upon us, the means, by which a state of things so desirable, must be preserved. It can only be by a vigilant and faithful care of those institutions, to the influence of which we are so much indebted. Should it ever happen, that the people of this state, losing their sense of the value of religion and the importance of education, should cease to make provision for their support; our school houses and places of religious worship, be deserted, and suffered to go to de ay, or be converted to other uses; and our Sabbaths, instead of being consecrated to religious retirement and social worship, become seasons of business or amusement; then will our children grow up in ignorance and irreligion, and in those habits fatal to all purity and elevation of character, of which irreligion and ignorance are the unfailing source. Throwing off their allegiance to God, what is to be expected, but that they will throw off their subjection to parental authority; having learned to trample upon the laws of Heaven, that they will not be slow in casting off their respect for human laws? Corruption thus introduced, by the neglect or perversion of education, how rapidly will the whole mass be contaminated! Nor will it be slow in passing from the people to the administration, and thence to the very principles of the government. Then instead of the august spectacle this day before us, of the wisdom and virtue of the state assembled here, in the presence of God, and invoking his guidance and blessing, to legislate for an enlightened, and free, and virtuous people, we should have an assembly of men whose recommendation to office and the public confidence, was their hostility to all that is most valuable in the character, and habits, and institutions of the country. And how soon such a change in the character of the administration would be followed by a correspondent change in the constitution under which they act, and in all those institutions, upon which the public order, the prevailing morals, and the prosperity chiefly depend, may easily be seen.

If, with the enlightened views and liberal spirit of our holy religion, on the other hand, and following the maxims and the example of our fathers, we shall continue to make competent provision for the support of religious institutions, and a system of education, that shall extend to those, who are capable of becoming useful to the public in the most important stations, opportunities and means for the highest literary improvements, and to all ranks of men such advantages as may qualify them to fill with propriety their place in the social body, make them capable of understanding the rights and the duties of citizens and of moral and accountable beings, and of feeling the influence of the highest and best motives in the conduct of life; we may feel secure of the permanence of a free government, that it will gather strength with time, and become venerable by age, as it is beautiful and attractive in youth; and that with it, all those institutions which we so much value, brought to a more perfect state, with the advancement of knowledge, and progress of improvement, will remain to shed their blessings upon our children, when we shall be gone to mingle our dust with the dust of our fathers.

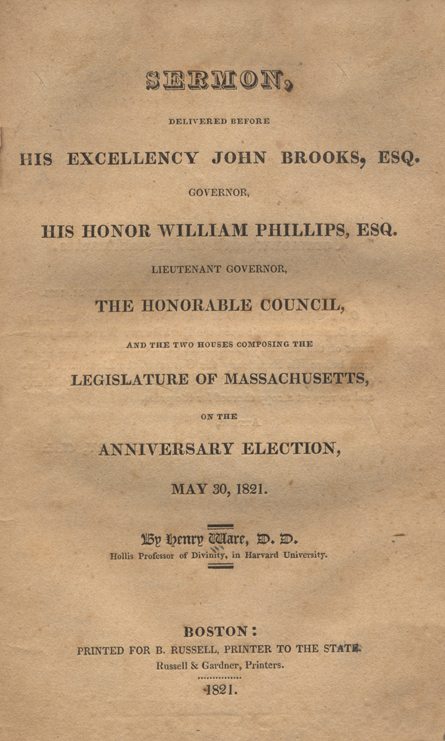

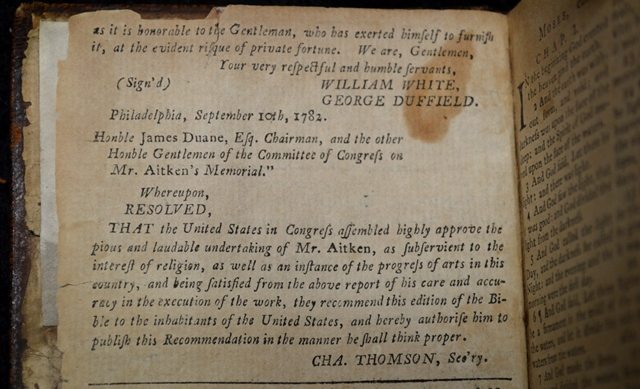

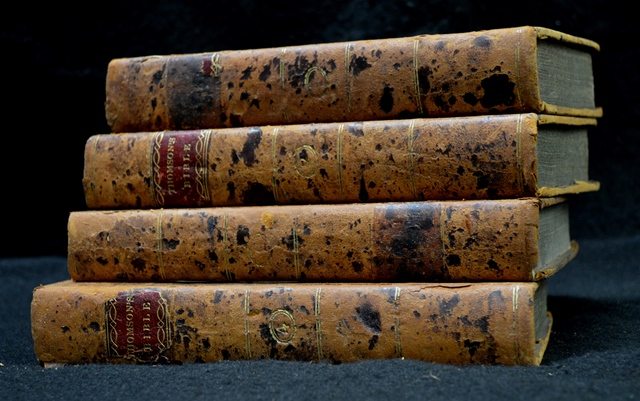

Though never a member of that august body, as Secretary of the Continental Congress for over fifteen years, Thomson had a front-row seat to the birth of the nation and his fingerprints are all over America’s establishing documents. For example, the copy of the Declaration of Independence included with the official Journals of Congress were in Thomson’s handwriting, and he was one of only two people who actually signed it on July 4th.

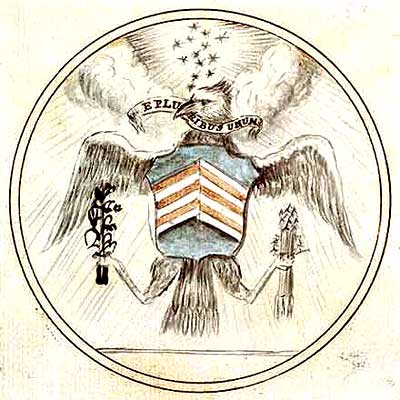

Though never a member of that august body, as Secretary of the Continental Congress for over fifteen years, Thomson had a front-row seat to the birth of the nation and his fingerprints are all over America’s establishing documents. For example, the copy of the Declaration of Independence included with the official Journals of Congress were in Thomson’s handwriting, and he was one of only two people who actually signed it on July 4th. Thomson is also responsible for the Great Seal of the United States, which he prepared and Congress approved in 1782.

Thomson is also responsible for the Great Seal of the United States, which he prepared and Congress approved in 1782. Thomson was also responsible for the first American translation of the Greek Septuagint (the full Greek Bible) into English in 1808 – a labor of love that consumed nearly two decades of his life.

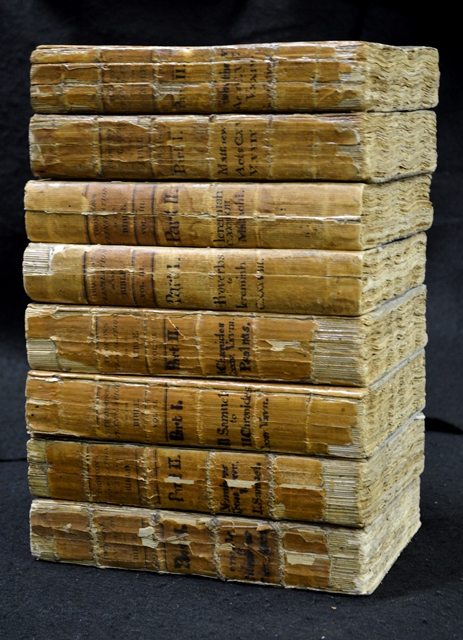

Thomson was also responsible for the first American translation of the Greek Septuagint (the full Greek Bible) into English in 1808 – a labor of love that consumed nearly two decades of his life. Thomson also produced an eight-volume set in which every other page was blank, thus allowing readers space to write notes on the Scriptures as they studied them.

Thomson also produced an eight-volume set in which every other page was blank, thus allowing readers space to write notes on the Scriptures as they studied them. In 1815, Thomson published his famous Synopsis of the Four Evangelists, in which he took all the passages from the four Gospels and arranged them chronologically, producing something like one super long Gospel, with all Jesus’ words and acts arranged sequentially. Today, we call such a work a synoptic Gospel.

In 1815, Thomson published his famous Synopsis of the Four Evangelists, in which he took all the passages from the four Gospels and arranged them chronologically, producing something like one super long Gospel, with all Jesus’ words and acts arranged sequentially. Today, we call such a work a synoptic Gospel.

[I] beg I may not be understood to infer that our general Convention was Divinely inspired when it formed the new federal Constitution . . . [yet] I can hardly conceive a transaction of such momentous importance to the welfare of millions now existing (and to exist in the posterity of a great nation) should be suffered to pass without being in some degree influenced, guided, and governed by that omnipotent, omnipresent, and beneficent Ruler in Whom all inferior spirits “live and move and have their being” [Acts 17:28].

[I] beg I may not be understood to infer that our general Convention was Divinely inspired when it formed the new federal Constitution . . . [yet] I can hardly conceive a transaction of such momentous importance to the welfare of millions now existing (and to exist in the posterity of a great nation) should be suffered to pass without being in some degree influenced, guided, and governed by that omnipotent, omnipresent, and beneficent Ruler in Whom all inferior spirits “live and move and have their being” [Acts 17:28]. As to my sentiments with respect to the merits of the new Constitution, I will disclose them without reserve. . . . It appears to me then little short of a miracle that the delegates from so many different states . . . should unite in forming a system of national government.

As to my sentiments with respect to the merits of the new Constitution, I will disclose them without reserve. . . . It appears to me then little short of a miracle that the delegates from so many different states . . . should unite in forming a system of national government.